Much has been written over the years about the so-called “Article of the Future,” with increasing awareness of the need to find, share, and cite research outputs as a whole, rather than continuing to focus on the article itself. PLOS’s current efforts to build what they’re calling a knowledge stack is one great example.

In this interview, Sami Benchekroun (Co-Founder at Morressier, VP Sales and Marketing, Products at Molecular Connections) and Rod Cookson (Publishing Director at The Royal Society) share their thoughts on how the traditional article format (and its digital successor, the PDF) has both shaped and limited innovation in sharing research outputs, and how a shift toward data-centric, reproducible, and machine-readable communication could open up new possibilities for integrity, accessibility, and policy impact.

Why do we need to move away from the article as the main unit of publication? What isn’t working?

Sami: The issue isn’t that the article is flawed – it’s that it has become overloaded with expectations it was never designed to carry. The journal article, particularly in its PDF form, freezes research into a static, final object. That made perfect sense in a print-constrained world where science needed a stable endpoint, but it no longer reflects how research actually happens.

Modern research is iterative, data-rich, and collaborative. Treating the article as the destination rather than a milestone creates real distortions: limited reproducibility, weak visibility into data and methods, and incentive systems that reward polished conclusions over a transparent process. The rigidity of the format also makes it easier to manipulate the system, because so much of the underlying work remains hidden.

At the same time, we continue to invest enormous effort in perfecting the presentation of the final PDF like typesetting, formatting, and version-freezing, while under-investing in the earlier stages of the research journey where quality, integrity, and reuse are actually shaped. That imbalance is not a failure of intent, but a misalignment of effort driven by legacy workflows.

What this points to is not the abandonment of the article, but a reversal of perspective. Instead of asking research to fit the article, we should allow the article to emerge as one expression of a much richer research output — grounded in data, methods, provenance, and governed change over time. The challenge ahead is not whether we can build these living research objects, but whether we can govern them well enough to earn and maintain trust at scale.

Rod: It is always hard to identify when something that has been hugely successful has run its course. The journal article is an excellent technology, honed over more than three centuries, which allows key outputs of research to be pulled together in a shareable form. Detail is necessarily lost in the process. That was a fair trade-off in the age of print, as there were finite limits on how much information could be captured in a single article. We are no longer in that age.

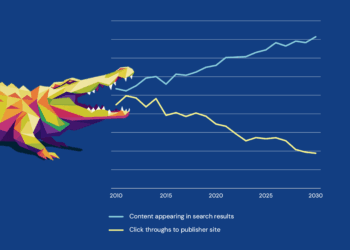

When the move to online publishing happened, the printed article was mapped directly across to the PDF file of an article. As Sami says, this locked the form of the article and stifled the evolution which should naturally have occurred. It also closed off the great online opportunity – enabling researchers to connect virtually, using articles as the nodes linking them, carrying the Invisible College into the internet. Instead, we continue to follow the rhythms of print publishing, with eTOC alerts triggering downloads and mirroring the despatch of printed journals, and then years elapsing before citations accrue. The greater speed promised by online dissemination, flagged by Paul Ginsparg as early as 1994, has yet to be fully realized.

Science has become more complex too. In subjects such as genomics, neuroscience, astronomy, and climate change, a single study can have gigabytes of essential data. For an entire project, that can extend to petabytes. Reducing so much information to a form that can meaningfully be contained within a traditional article is impossible. Indeed, this discrepancy is a root cause of the Reproducibility Crisis.

Research outputs also come in many forms, including datasets, code, 3D models, software, videos, maps, and more besides. Squeezing them into a text-based article format conceived in two dimensions produces unsatisfactory outcomes.

What is needed now is a change of mindset, reversing how we conceive of the article. The research output needs to become the centre of what we publish. There is still a role for accompanying text as, essentially, human-friendly metadata. But we should understand that the research output itself matters more than what we write about it, and that many readers are no longer human and machines have different needs to ours.

Conversely, what is working – what don’t we want to lose from the current system?

Sami: We shouldn’t discard the core structures that create trust and coherence. Peer review, despite its flaws, still provides essential expert validation. The narrative layer helps contextualize why findings matter. And the architecture of credit, PIDs, citation practices, and versions of record, gives stability to a fast-moving system. These elements should evolve, not disappear.

Rod: There are virtues to the article and its PDF facsimile. Articles are Versions of Record which crystallize research results in a way that others can build on. The PDF is a robust archiving format which remains accessible using free software that can be downloaded in seconds. (Compare that to trying to read a WordPerfect 5.1 file saved on a 3.5 inch or 5.25 inch floppy disk today.) A PDF also retains the precise layout of an article. This matters in disciplines like mathematics where exact presentation of formulae is essential. And, depending on the field, a conventional article may contain all the information needed to completely understand a piece of research and replicate it.

These functions – authority, stability, accessibility, precision, and in some cases comprehensiveness – are still hugely important. We should not lose sight of them.

What are some examples of initiatives in this space that you’re keeping an eye on and why?

Sami: I am closely watching the startups and infrastructure players that are rethinking research from the ground up, not just how we publish, but how science is produced, shared, and validated.

On the startup side, companies like Code Ocean, Colabra, BenchSci, and Dotmatics are interesting because they blur the lines between lab work, data management, analytics, and publication. They treat the digital research workflow as a continuous stream rather than a set of disconnected tools. This shift, turning experiments, data, and code into structured, traceable, and reusable objects is exactly what will make “living research” possible.

I’m also watching initiatives around AI-native lab environments, where experiment planning, execution, and interpretation are increasingly machine-assisted. These create research artifacts that are far more transparent and connected than anything we’ve had before.

And then there are the systemic drivers:

- FAIR data mandates from funders

- Open-lab notebook movements

- Persistent Identifier (PID) expansion into every layer of research

- Preprint-to-publication workflows that treat research as a continuum

All of these point toward a future where the “unit of science” is no longer a PDF but a rich, evolving digital object grounded in data, workflows, and provenance. That’s the direction of travel, and these initiatives are accelerating it.

Rod: Journal publishing is already changing, as the question implies. For example, Octopus sub-divides articles into their essential components and encourages authors to include everything that is relevant to the research they are sharing. Each element has a DataCite Digital Object Identifier (DOI) and can be separately cited. The ‘article’ structure is modular, so what Octopus labels a “Research Problem” can first be articulated, with updates added as a project progresses. One of the reasons this is interesting is that Digital Lab Notebooks (confusingly referred to as ELNs) capture information in a structured form, which can feed directly into a publishing system like Octopus. Articles can be published in stages in real time, which can be a great virtue. During the COVID pandemic, for instance, rapid sharing of genomic datasets speeded the scientific response. The exact data from an ELN can be carried across to Octopus, as can reproducible workflows used in an experiment. These are steps toward much higher levels of reproducibility in the published research. From a practical perspective, components of articles such as method sections, data tables and figures can be generated automatically and fed into Octopus, simplifying the writing process.

Björn Brembs has been undertaking automated publishing of ‘articles’ for some years, part of an explicit reconceptualization of the journal system.

Alchemist Review is experimenting with tools that give insights into an article before the reader has opened it, giving a sense of its novelty and significance. These tools are designed with evaluation of submissions in mind at present, but they could easily link related research outputs across online platforms and steer readers toward high impact articles which are likely to interest them before citations have accrued.

What links these initiatives is a pivot from laborious copy-editing and typesetting of articles to sharing research outputs rapidly and allowing readers to focus on what is exciting and relevant to their work. Taken together, these changes could constitute a revolution in our publishing system.

Where do you think we will end up, what will a future “living article” look like?

Sami: A living article will be dynamic, versioned, and deeply linked to the underlying research process. Instead of a static document, it will function as an evolving knowledge object that combines narrative with data, code, methods, and context. Readers will be able to inspect analyses, understand how results were produced, and track how findings change over time.

Crucially, this isn’t about instability. Governance, provenance, and version control become even more important in a living system. Change must be transparent and accountable. The result is something that serves both humans and machines: readable narratives for people, and structured, computable objects for AI systems that synthesize, validate, and reuse research at scale.

Rod: Yes, this is where it gets really interesting. An article today is fundamentally a discrete object. In future, a ‘living article’ may be more like an ecosystem, bringing together outputs like datasets with code that might be executed on it, multi-media files, and of course explanatory text. The text may be presented differently using AI tools to tailor it to the reader’s needs, with different presentations for researchers, policy-makers, and lay readers. There still needs to be version control, so that science has solid foundations to build on, but with platforms like Octopus an author could add to an existing ‘article’ as further research refines the findings recorded in it. This would enable the article to ‘grow’ over time, just as an ecosystem does. Pugliese et al describe something very similar in their ‘agentic publication’.

The reading experience of a ‘living article’ might be different too. AI tools could enhance abstracts, for example, with references to work published after the article the reader is looking at, indicating that some of its findings may since have been challenged. That is useful information for a reader.

At a higher level, machine-readable and well-structured articles could feed meta-analysis tools. This might be something like a Wikipedia of Science, fed by LLMs but curated by humans, or an entirely automated platform in which Generative AI summarizes key findings on a topic. Naturally, such future tools would evolve over time as the ‘living articles’ they draw on change.

Do we have the right infrastructure to support these changes?

Sami: Not yet – but we are closer than we’ve ever been. Many of the building blocks already exist: PIDs, open APIs, data repositories, reproducible toolchains, and community standards. The problem is that they are still loosely connected and often constrained by print-era assumptions.

Incentives remain misaligned with incremental, data-first contributions, and interoperability across systems is uneven. What’s missing is a coherent architectural layer that treats research outputs, not documents, as the primary objects of record. The challenge ahead isn’t invention so much as integration: connecting existing components into infrastructure that supports governed change, reuse, and long-term stewardship.

Rod: As Sami says, we have elements of the infrastructure, but in most cases it is not organized in a way that enables the changes we are discussing. For example, IOP Publishing gives separate DOIs to supplementary material and PLOS requires authors to deposit datasets in repositories where they have their own PID. Articles in Scientific Data are structured rather differently to traditional journal articles, even if they can still be accessed in PDF form. These are steps forward.

Moving to a world where datasets and other research outputs become the center of articles, with live feeds from ELNs and continuous updating of results, involves an order of magnitude more change. For good reason, online platforms need to sit on solid architecture. This architecture would need to be completely reconceived for ‘living articles’. Octopus is one of the platforms that shows us the possibilities. We are still a long way from these possibilities radically reshaping how scientific research is shared.

Where do you think we will be on our journey towards a “living article” in five years time?

Sami: In a transition phase. PDFs will still exist, but they will hopefully no longer define the system. Many publishers will support versions, incremental outputs, and direct links to FAIR data. Funders and institutions will start valuing contribution trajectories instead of just the final results. And artifical intelligence will accelerate the shift, because AI systems require structured, computable research objects. We’ll be well on the way toward a more dynamic model – even if we’re not fully there yet.

Rod: Nothing changes fast in our world! We are 35 years into having pre-print servers and they are still maturing. It took journals 150 years to develop abstracts and 300 years before peer review became a standard feature. So I am not holding my breath. Five years is not a long time in which to re-engineer a complex system of interlinked software and platforms, especially if there is not a commercial imperative to do so.

Perhaps a different question is needed. If someone does succeed in linking articles to the tools used by scientists in their work and create ‘living articles’, will this be a new kind of journal with vastly more impact than the journals of today and which is a magnet for authors as a result? Should that happen, our world in five years time could be very exciting indeed.

Discussion

7 Thoughts on "Back to the (Article of the) Future: An interview with Sami Benchekroun and Rod Cookson"

Rod frames this cautiously, but RSP’s seminar programme is already a practical expression of the “Invisible College” idea — research shared and connected in more online-native formats alongside the article.

Example “Author Seminar”: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/rsos/article/11/3/230603/92609/Giant-sequoia-Sequoiadendron-giganteum-in-the-UK

Disclaimer: Cassyni co-founder.

Thanks Ben – one of many extremely interesting steps toward a different future

Thanks. Critique is very on point. Furthermore the “paper” is increasingly less of the useable science from research. The data and code and methods are and this disconnect is growing as the current pdf focused model persists. Articles of they future have failed bc they are even more disconnected from research workflows and require more specialized work. I’d advocate for publication notebooks as the future because: 1. Researchers are already using notebooks extensively for their work. There are more than 11M notebooks and growing. A publication notebook can link natively and functionally to this work data processing and code and researchers can directly integrate them. 2. Examples are already available ( see https://curvenote.com/ and also notebooks now! Work). 3. Publication notebooks already support various outputs like pdf xml and html so allow integration with downstream workflows and services. No need to reinvent that 4. They allow and support rich presentations in animation and data visualization and user manipulation and 5. They allow researcher communities of practice to innovate for example in developing widgets for animating their types of data thus engage them in the publication and communication process. They become engaged stakeholders 6. They support rich markup and can reduce expensive platform dependencies allowing publishers to focus on replication and trust vs presentation bc they are built directly on a platform (git) designed for reuse. 7. Linking to research directly helps transparency and will make it harder to fake. And much more. In sum, engage researchers and more research outputs in a solution that scales as the research scales.

Very eloquently put, Brooks – thanks for the expansion of our thoughts

I agree Brooks that using a kind of “notebooks” approach to switching up the efficacy of articles to both, communicate findings of research but also validate those findings from peers, being essential to the retention of trust in scholarly evidence. I’d also point to this tool (which has already been around for quite some time and is incredibly useful for communication on web documents), https://web.hypothes.is/ – This is like a conversational wiki/overlay on any page on the web – including PDF documents. The hypothes.is browser extension could be utilised to bring live feedback into the peer review process in real time to engender validity, trust, publication chops basically. I’m so surprised this tool is not more widely used in scholarly communications as I think it would totally ramp up the scope of the article to that of communication again. Live, real-time, evidence-based, validation of the data behind the discussion. Desperately needed and the tools seem to be already available.

At agu we tested hypothesis.is for both peer review and comments on papers for several years. Comments are still possible. Mixed uptake on both but not a lot of adoption. Maybe with time. It’s a good tool for both imho.