Editor’s note: Today’s post is by Jeff Lang, Founder of FigureTwo, a tool that helps researchers create engaging, transparent, and understandable figures.

The FAIR data movement has taught us all the value of Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable data. Within the research community, awareness of FAIR principles has grown from 15% in 2018 to more than 40% in 2025, according to The State of Open Data report by Figshare and Digital Science. Funder data mandates have flourished in recent years, and data repositories are full of permanently archived files. Yet, even in this proliferation of data, we should be asking for more.

Data may be FAIR while still not understandable. And, we should seek to increase understanding of research data across all the communities that rely on it, from academics to policymakers to the general public.

Looking back

At 10 years old, the FAIR principles seem presciently crafted for today. “The principles emphasize machine-actionability (i.e., the capacity of computational systems to find, access, interoperate, and reuse data with none or minimal human intervention) because humans increasingly rely on computational support to deal with data as a result of the increase in volume, complexity, and creation speed of data.”

We’ve seen the exponential acceleration of AI capacity and capability since ChatGPT’s public launch in late 2022. Feeding this surging miasma of research data into sophisticated machines has, and undoubtedly will, lead to a cascade of new ideas and positive outcomes. And yet, those same sophisticated machines threaten to drown us in data that ranges from miraculous to absurd. Data volume cannot measure our rate of generating new understandings, nor does it assure the uniform distribution of understanding across the population.

As an aside, this week we’re recognizing another 10-year anniversary. This is I Love Data Week, an annual celebration of research data and an opportunity to reflect on its place in the scholarly communications ecosystem. I don’t know whether the timing of these two events in early 2016 was a coincidence or if they share a common inspiration. But, it seems reasonable to me that the FAIR data principles are a genuine expression of love for research data. February is the season of love, and many people in the scholarly communications community are known for their research data fandom. I’ve seen more than one office with an Edward Tufte poster displayed prominently, like concert swag.

“U” is for Understandable

Understanding is the human element that gives data value. It’s the difference between “information” and “knowledge”. When data is understandable, it allows us to make decisions and take actions that affect us and the world around us.

Information is like the small text on the large paper insert inside a pharmaceutical prescription package; understanding that information requires drawing on existing knowledge. Even when I can read every word (and that’s not a guarantee with small fonts, flimsy paper, and low-quality printing), I frequently lack the vocabulary and context to understand all of the directions and warnings. Of course, these inserts are not meant to increase understanding by the typical customer. For that matter, neither are the pharmaceutical advertisements that run so often on every media source in the United States. While the inserts are meant to comply with mandates and suggest expertise, the ads are designed to stir demand through deliberately limited information. Both succeed in presenting data that translates to a limited understanding of the product.

What about the “A” in FAIR? Doesn’t this imply understanding? In the context of information services, the term “accessible” is already overburdened with many alternative meanings and, unfortunately, understanding is not one of them. The FAIR principles define it using many other “A” terms, including “authorization,” “availability,” and “actionability for machines.” These are all important, but they do not suggest understanding. If we were to generously interpret “accessibility” in the sense of the WCAG (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines) standards, we would be talking about helping people overcome barriers to understanding. That would at least be adjusting the focus to people rather than machines, but that is well beyond the stated goals of FAIR.

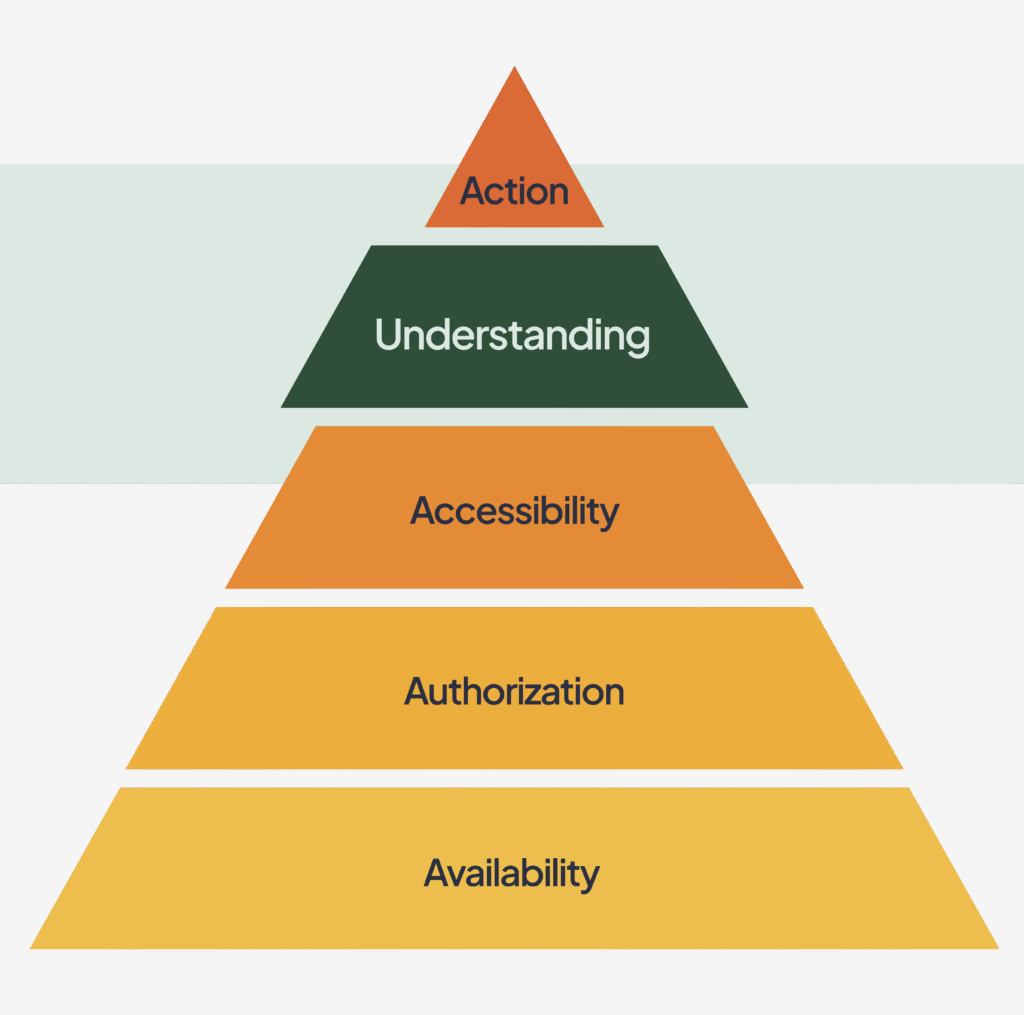

A Hierarchy of Understanding

I prefer to think of understanding within a hierarchy of needs, with many of the FAIR principles and accessibility (in the WGAC sense) forming the foundation and early levels. Understanding can be thought of as a high-order function that can only be attained when the needs for availability, authorization, and accessibility are met.

The base layer in this hierarchy is aligned with the “Findable” attribute of FAIR. When data is not findable or available, we cannot hope to understand it. Under the FAIR framework, both “Accessible” and “Reproducible” refer to metadata elements that provide a person or a machine with access, authorization, and context for data. This covers structured access to the metadata, as well as the structure of the metadata itself (license, authorship, protocols, etc.). “Interoperable” can be viewed as the machine-oriented version of human accessibility (in the WCAG sense). Both humans and machines need information to be well structured and presented in a way that suits many different methods of engagement.

My undergraduate philosophy courses don’t prepare me to address the question of whether machines are capable of truly understanding the data that they process. But, for now at least, machines process that information based on human requests. So, human evaluation and understanding are required for any research data to have meaning or value.

The pinnacle of this pyramid is “action,” where people make decisions using data and their understanding of that data. Machines may help us reach that understanding or take that action, but action without understanding is surely a recipe for disaster.

Conclusion

I remain awed by the sophisticated machines that help us collect and process research data. Their capacity to improve our lives is so much greater than I would have anticipated a short while ago. The research community’s embrace of the FAIR principles represents genuine progress towards a better understanding of our world by the greatest number of people. I would like to encourage our community to take the next step required to turn FAIR data into understandable data. Make “understandable” a priority in everything we do. Let’s not leave the data to the machines at the expense of our own understanding.