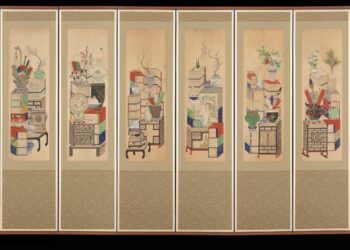

- Image via Wikipedia

A recent post on O’Reilly’s Tools of Change (TOC) sums up what I think is an artificial distinction that has crept into the discourse of publishers facing disruption and upheavals — that is, are publishers in the business of providing content or service?

Andrew Savikas argues that content is a service, a perspective I’m fairly sympathetic to. After all, Google doesn’t want our content — it wants our links. They have turned content into a service to the tune of a few billion dollars. So has Amazon — they don’t want your content, but they provide services to get people to content and let them buy it.

The fact is that both are inextricably linked, but the balances are different depending on what you emphasize. There is a fallacy that you can separate the two. Google can’t, and publishers have been slow to realize the leverage this creates for them. But Savikas argues to the fallacy rather forcefully:

Whether they realize it or not, media companies are in the service business, not the content business. Look at iTunes: if people paid for content, then it would follow that better content would cost more money. But every song costs the same. Why would people pay the same price for goods of (often vastly) different quality? Because they’re not paying for the goods they’re paying Apple for the service of providing a selection of convenient options easy to pay for and easy to download.

He must not have shopped for music lately on iTunes. More popular items often cost more now. Artists are releasing single hits for $1.49, well before their album comes out. American Idol is getting $1.29 per song during the competition, and creating scarcity to drive up the price.

I also wish this iTunes analogy would go away. While I’m all for what Geoff Bilder advocates — frictionless e-commerce for scholarly content — the rest of the iTunes analogy breaks down pretty quickly. As a service, iTunes isn’t really all that great — it’s the content and frictionless e-commerce that works, but as a music mixing engine, I’ve seen better. And the content on iTunes is different than scholarly articles — it’s finished works of art (songs, videos, movies) that people would want to experience in a linear fashion and own as defined works of art. Scholarly communication is about non-linear access to key information. You don’t go experience a Beck song with a highlighter in hand.

Publishers have been about providing content through assemblage and distribution of printed materials — a service. Everything that was made invisible to users indicates the level of service, from securing the printing contracts, buying and warehousing the paper, and funding the postage to the editorial travails and work of running a large enterprise. Publishing is a familiar content-service hybrid.

David Crotty does a good job describing a world of service alone in his post about the vacuousness of Web 2.0 without anything behind it. Web 2.0 is a service-oriented implementation of the digital network. It can be used to purvey goods. But without anything to sell, it’s just an empty service.

What has changed in the information business is how the services are being arrayed and what counts as content.

A recent article in Fast Company about how blogs follow mainstream media hits on the same issue, but draws the wrong conclusion. The article claims news organizations should relax since they still have the first journalism. But what they don’t have is the best service for getting the journalism out or interpreted. Did you know about this Fast Company article before you read this? Did you realize it might be relevant to STM publishers? Blogs are a Web 2.0 service layer around information, and bloggers are providing both content and service. They’re inseparable.

While content is important, the converse is also true — without the service side, content or goods drop in value and utility, especially in the networked world. They’re hard to discover and difficult to understand or apply. Every author needs marketing and retail help to reach his or her audience. Judging from the effect the New York Times is seeing, the mainstream media needs bloggers, Twitter, and Facebook.

In an economically challenging environment, publishers have to adjust both their content and their services to a new digital space that’s inventing some different rules.

The two can be separated, but only to the detriment of both.

Discussion

1 Thought on "Service or Content? Another False Choice"

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=07c0e578-75f8-46b3-906e-a545d24c5aa1)