- Image by William & Mary Law Library via Flickr

Recently, OCLC released “How Libraries Stack Up: 2010,” an infographic montage that is apparently intended to illustrate “the economic, social and cultural impact of libraries in the United States.”

If you’ve been to a public library recently, there’s no doubt they’ve diversified, shifting their role from mainly providing books and a safe, quiet space for reading and study to encompass a host of other activities:

- Providing job-seeking help

- Offering free wi-fi hotspots

- Teaching technology classes

- Offering conference rooms

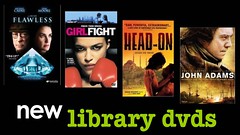

- Lending DVDs

- Shuttling materials for ILL

Looking over the infographic, it’s easy to be impressed by the numbers and comparisons. It’s slick, nicely illustrated, and some of the comparisons are pleasantly surprising (e.g., public libraries distributes as many DVDs as Netflix).

But does distributing a used DVD of “Fight Club” really contribute to the US economy? In fact, should the premise be economic at all?

Problems with the comparisons emerge in the light of economic contribution. For instance, while the OCLC infographic shows that FedEx ships 8 million shipments worldwide every day, libraries circulate 7.9 million items. FedEx ships items long distances quickly and has little warehousing overhead. Libraries circulate local materials from an inefficient warehousing system (stacks) and can’t throttle or expand capacity based on demand — their capacity is essentially static (too large most of the time, in fact). FedEx is much more efficient at doing its work than libraries possibly can be, given the other demands on them (warehousing, local availability, staffing). FedEx costs users when used, generates profits for shareholders, and contributes directly to the economy. Libraries’ economic contribution is much more indirect, if it’s even a net-positive when it comes to transport and disbursement of materials.

Consider the comparison to movie theaters, which notes that libraries have 1.3 billion visits per year while movie theaters have 1.4 billion attendees per year. The comparison is weak. Movie-goers spend 1-3 hours in the theater each time they go and spend money on overpriced snacks. Visits to libraries are shorter, often lasting only minutes. And a visit to the library doesn’t stimulate the economy, while visits to movie theaters generate ticket sales, concession purchases, and so forth.

Providing DVDs at no cost is not an economic contribution. Saving money is not economic stimulation. In fact, the recent trend for Americans to sock money away for a rainy day may be contributing to a longer recession than normal.

So, this is just a quick plea for libraries and their advocates not to fall into the trap of measuring by the currently tractable measure of economic contribution.

Libraries should be measured by their civic value, not through comparison to economic powerhouses like Netflix, FedEx, Starbucks, or VISA. What libraries contribute to our culture goes beyond economic measurements. To allow the debate to shift on to economic grounds is potentially problematic for library advocates.

If libraries were to be measured by economic contribution rather than, as the subhead on the OCLC infographic states, because they are “at the heart of our communities,” the gravestone on a library may not read RIP — it made read ROI.

Discussion

3 Thoughts on "The Mismeasurement of Public Libraries — via FedEx, Netflix, Starbucks, and VISA"

Agreed! Libraries are terribly important to the learning potential of the country: they offer free resources to patrons who otherwise may not have access to books, music, movies, and often the Internet. Reading is one step toward better education and awareness, and smart, knowledgeable children are a greater–albeit less directly measurable–asset to the economy than any NetFlix profit share.

Ironically science itself has the same problem, in that no one can measure the ROI. Some of us are working on this problem, see http://www.scienceofsciencepolicy.net/. Given that the economic value of science cannot be determined the same is true for scientific communication (including libraries), apart from direct income that is. In the meantime the whole science enterprise does indeed look overstocked and slow.

My view is that this is because science is a diffusion process, so tracking of economic impact is impossible. As Dr. Bruce Robinson, then head of planning for ONR, once put it eloquently to me: “All I know is we fund sensor research and the sensors keep getting better.”

The open question is how to measure this diffusion, including for libraries. In the meantime our ignorance is not a conclusion to be drawn, it is a problem to be solved.

While I agree with your fact-free sentiment, I don’t agree that the economic contributions of libraries are not good reasons for them to exist.

Your assertion that DVD lending does not contribute economic value is in conflict with the conclusions of economists who have looked at the issue. I wrote about this in January.

If you had asserted that MP3 lending would not contribute economic value, you would have been on stronger ground, which is why there’s been a lot of discussion about how libraries will survive in an ebook economy.

Measuring the economic value of the “civic role” of libraries is of course harder; I’ll search the literature to see what’s been done.