- Image by Getty Images via @daylife

This is a short post on a big topic.

Google has opened up its database of digitized books to researchers, who are mining the data for trends and patterns. The New York Times has a stimulating summary of the project, and only a person completely lacking in curiosity could fail to be fascinated by some of the early findings.

How far can this go?

It’s hard to say at this juncture, but my guess is that the emergent properties of large databases will prove to be very rich indeed.

What jumped out at me in the Times‘ coverage, however, was this statement:

Google says the culturomics project raises no copyright issue because the books themselves, or even sections of them, cannot be read.

How’s that again? It looks to me as though someone slipped a curve ball by the batter.

A copyright is a right to make copies. But here we are told that a copyright only applies when there is a human reader. Machines can read, too, and creating and repurposing content for them is a significant growth opportunity for the publishing industry. On what authority does Google assert that human readership is an essential aspect of copyright?

To my knowledge, publishers have shown little interest in asserting their rights in data-mining projects. Perhaps that will change if the results of these experiments with the Google book database prove to be significant.

Discussion

51 Thoughts on "Data-mining Google Books: Does the Reader Have To Be Human?"

I would argue that machines cannot read. Would that they could since I work in the field of text analysis, mapping and search. The term “machine learning” is part of the entrenched hype of artificial intelligence. Algorithmic manipulation of text strings is not reading.

On the other hand the courts might well decide that machines can read for the purposes of this specific copyright issue. That makes it very interesting to our community. Nice find.

To find select words or phrases in all the scanned texts is NOT, human or machine, to read

beyond the ‘fair use’ doctrine….anyone now, human or machine, can ‘read’ like this in any new or still-copyrighted book.

Locked within Google’s archive are some of the world’s best derivative works. Using text mining it is and will be possible to, (for example) create directories, statistical tables, gazetteers, photograph books, and genealogical tools of enormous size and sophistication. As facts become ever easier to extract and synthesize so the archive will be able to answer ever more sophisticated questions.

We can argue whether or not machines can read. We can all agree that the results generated by such machines will be read by humans. Such work is surely derivative and so deserving of copyright?

The various products you describe are not build-able from the data mining tool at issue: http://ngrams.googlelabs.com/

If you do a study using Google’s tool (as I have already begun to do, looking at the history of the concepts atomic, nuclear, nuclear power, etc.), then I assume you can copyright your study. You cannot copyright the output from a specific mining search. If anyone owns that it is Google. The question is whether the search itself is illegal if the underlying data (the books) are copyrighted? I think not but courts are unpredictable.

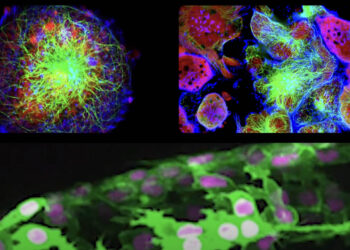

I love this tool! It fits with my team’s work using a disease model on new language to map the frontiers of science. (The frontier of science is one of the frontiers of language.)

Here is arguably the greatest, and saddest, single jump in the popular understanding of science. The word “atomic”:

http://ngrams.googlelabs.com/graph?content=atomic&year_start=1900&year_end=2000&corpus=0&smoothing=1

Congress has repeatedly declined to include protection of databases as falling within the scope of copyright, unlike EU countries, so to the extent that Google can claim to be using the books scanned just as data, it probably has a good argument. The mere fact of scanning an entire book, however, makes that act putatively an infringement, and that’s why Google was used by publishers. Google argues that its use is fair because of its “transformative” nature, relying on a series of decisions about “tranformative use” in the Ninth Circuit. I personally think those decisions are wrongheaded, but the Settlement Agreement will make this all moot, if Judge Chin approves it.

Sorry to get carried away but this is my field and here is another historic hummer (evolution and Darwin):

http://ngrams.googlelabs.com/graph?content=evolution,Darwin&year_start=1840&year_end=1940&corpus=0&smoothing=1

Regarding scholarly publishing the 9th Britannica (circa 1890?) had a brief note on “evolution,” mostly about a strange theory by one Darwin. The 11th Britannica (circa 1910) had a long entry written by Thomas Huxley, Darwin’s “bulldog.”

Indexing of books by itself is well established as not infringing copyright at all; Google’s point about the books “not being able to be read” is meant to indicate that ngrams is just an opaque index.

It’s possible to make an index that is not opaque; in other words, an index from which the works themselves can be reconstituted. Publishing such an index would probably violate copyright.

I’ve written more on this topic on Go To Hellman.

I’m prepared to be told I’m wrong about this, but I’m not sure copyright law actually has anything to say about reading, either by humans or by machines. Copyright is the right to make copies, to distribute copies, to make derivative works, to perform, and to display; it has nothing to say about the means by which a lawful copy is read — it addresses only the rights to make copies (or derivatives) and distribute or perform them. So if I’m correct on that point, then it seems to me that the copyright question is relevant at only two points: when Google digitized the books and when it made them available to the public. Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that the copying itself was permissible under fair use. Now the question is whether making the copies publicly available for searching (but not for reading) constituted fair use. Again, for the sake of isolating the reading question, let’s say it did. Does copyright law at that point have anything to say about who (human or otherwise) then reads those copies and how? I don’t think it does. I think Stephen has a point about the creation of truly derivative works based on mining of the Google corpus, though I think it would only be an actionable point if it could be proved that the work in question was derived from a single copyrighted work.

The Intellectual Property Colloquium at http://ipcolloquium.com/mobile/2009/09/derivative-work/ provides an hour plus presentation on the derivative work right based on the successful lawsuit against the Harry Potter Lexicon.

The questions you raise above are equally applicable to search engines as well as to book indexes. Every webpage is copyrighted under the Berne Convention. Google (or Bing, or whoever) does not ask permission to copy the page into an index and redistribute it as part of that index. Search engines are a strictly opt-out business, as you have to add a robots.txt file to your page to avoid being indexed and included. If it’s a violation of copyright for Google to scan the books and create an index and to make that index publicly available, then isn’t Google’s regular search engine illegal as well?

My comment was based on the assumption that is _isn’t_ a copyright violation for Google to scan the books and create a publicly searchable index (or at least that it’s a legally allowable violation under Fair Use doctrine). In fact, as you suggest, I think the legal viability of Google’s regular search engine provides a strong precedent to support the viability of publicly indexing the Google Book scans. The former uses dynamically-generated copies of web pages; the latter uses manually-created copies of printed books. The copyright principles involved in both cases seemto me to be very similar.

You’re correct about the law itself, and it may seem a bit tree-falls-in-a-forest-ish, but the relevant legal decisions which have addressed the what-is-a-copy question seem to put weight on whether a supposed copy (such as when copyrighted material is loaded into RAM storage) can be perceived by humans.

I believe Rick is correct about the law. And David is of course right about Google indexing being an “opt out” enterprise in relation to web pages. But what Google tried to do is to rewrite all of copyright law to make it accord with that “opt out” approach, and that is what authors and publishers challenged in court. It is significant that the Google Settlement accepts that “opt in” should apply to all in-copyright, in-print works; “opt out” in the Settlement scheme applies only to “orphan works.” So Google has tacitly conceded that its argument about fair use for in-copyright, in-print works was not going to prevail in court. Google was relying too much on those Ninth Circuit court decisions, which in the arena of fair use have been on the fringe of judicial interpretation.

I think that’s the real problem I have with the Google books settlement (actually one of the two, the other is the monopoly issue that requires other companies to break the law to compete). Rather than lobby Congress to change copyright law, Google is trying to do an end-around, attempting to rewrite copyright law via a private settlement of a civil suit. They’re essentially trying to overturn US law and various international treaties, all without any intervention from the governmental institutions that are charged with creating those laws.

By all means, we should have access to orphan works, but we need laws that permit this, not the backroom dealings meant to entrench one company’s financial position that have happened here.

And I’m sure Google would never publicly admit that they were conceding anything as far as fair use. Instead, they opted for a path that allowed them to avoid any risk of a judgment against them, and that provided all sorts of extra-legal benefits to their business. Quite a strategy!

Isn’t it an exaggeration to say that the settlement seeks to “overturn US law and various international treaties”? The settlement’s terms will apply only to those who are parties to the settlement; it’s not going to change any law on the books. Granted the parties constitute a huge number of copyright holders, but it still seems to me that there’s a major legal chasm between the terms of a legal settlement between parties and an actual change in code. (I can limit my own free-speech rights by agreeing to a confidentiality clause, but that doesn’t mean I’ve overturned the Bill of Rights.)

No, I don’t think that’s an exaggeration. The “parties to the settlement” include every single person who has ever written a book, every publishing house that has ever existed, and it goes beyond that–note that there’s a second lawsuit filed that addresses the question from the point of view of the artists and photographers who created the artworks in all of the books Google has scanned, the rights to which are not addressed in the current settlement. Furthermore, the original settlement (since slightly amended but still not enough to satisfy most) makes non-US citizens a party to the terms of the settlement, without notification or consent (hence the violation of international treaties). If Google scans in a book that was never published in the US, the settlement gives them the right to become the de facto US publisher for that book without seeking permission from the non-US author.

The key though, is that it’s opt-out. Yes, you can choose to limit your own free speech rights. In this case, you don’t get to make that choice, essentially your rights are taken away from you unless you make the effort to opt-out and reclaim them. That’s why I see it as an overturning of law. It takes away copyright unless you take some action, which is contrary to the Berne Convention (“Copyright under the Berne Convention must be automatic; it is prohibited to require formal registration…”).

But David, the fact that you “see it as an overturning of law” doesn’t change the fact that, in reality, no law is overturned by the settlement. The settlement doesn’t reassign anyone’s copyright to Google. That said, you make a very good point about the opt-out vs. opt-in problem in my “free speech” example.

Yes, it does reassign copyright for any orphaned work, or really, any work where Google can’t figure out who owns the copyright. They get to go ahead and do what they want with the work at that point. And that’s essentially a reassigning of copyright, which should be done through legislation, not private backroom dealings.

Responding to this:

“Yes, it does reassign copyright for any orphaned work, or really, any work where Google can’t figure out who owns the copyright. They get to go ahead and do what they want with the work at that point. And that’s essentially a reassigning of copyright, which should be done through legislation, not private backroom dealings.”

But unless Google gets that legal right exclusively (and I’m pretty sure it doesn’t, though if you can point me to where in the settlement that right is granted exclusively, I’ll be happy to be corrected) then it’s not the same thing as reassigning copyright at all. It’s the same thing as treating the work as if it were in the public domain, which seems like a fairly reasonable solution for an orphaned work until the rightsholder can be identified. Copyright isn’t just about what you can do with the work — it’s mainly about what you _alone_ can do with the work.

I am not a lawyer and may be mistaken, but this agreement is between Google and the Author’s Guild/AAP. No other company is granted the legal rights to copy, distribute and sell the orphan works in question.

That’s the issue, as I understand it, that the Department of Justice has with the settlement. It gives Google monopoly access to orphan works. If anyone else does what they’re doing, they are essentially breaking the law. The only way to compete with them is to break the law, get sued, get it declared a class action lawsuit, then negotiate a similar settlement.

The works aren’t being put into the public domain, they’re remaining under copyright, but Google is being given exclusive permission to violate those copyrights.

But “orphan” means more than just in-copyright-but-out-of-print — it refers to works for which the copyright holder can’t be identified. Once a copyright holder identifies himself, the work is no longer an orphan, and then the opt-in condition would hold. Isn’t that right?

I entirely agree with you, David, but so far Congress has punted on the issue of “orphan works,” despite having a bill proposed that both librarians and publishers (who rarely agree on copyright matters) supported ant that the highly respected Register of Copyrights recommended. Google pursued a strategy that, if successful,will bring it the greatest benefits at the least cost–the very definition of rationality, is it not? What’s good for Google, however, may not be good for the rest of us.

That’s one of the keys here–it’s a great deal for Google, not so great a deal for anyone else.

Well, other than the general public. I mean, we all agree that the settlement is far from perfect, but let’s not lose sight of the unbelievably enormous benefit that the Google Books project has already provided to everyone in the world who has internet access but doesn’t have access to a major research library (which is to say, millions and probably billions of people).

If the point is to benefit the general public, then why not open up the settlement to any interested party? Why not grant the same blanket rights to anyone who wants to create such an index? Why is Google allowed a monopoly on the world’s knowledge?

The Settlement provides for the new Book Registry to keep funds in escrow that will be paid out to copyright owners of orphan works if they should later come forth to identify themselves. If such funds are not claimed after a certain number of years, then the Settlement designates how they are to be used.

The reason that the parallel with indexing of web sites does not hold up is that the libraries that allowed Google to scan books in their collections received a quid pro quo, in the form of a copy of the Google file. That is a “copy” of the whole work that otherwise the library would not be able to make, unless permitted by Sec. 108, and would have to purchase from the publisher. Thus there is harm to a potential market. The focus on the “snippets” mislead people to ignore the real copyright infringement issue involved in Google’s Library Project.

The Settlement does not apply to works by most foreign authors now, nor does it apply the “opt out” principle to anything but “orphan works.” Google cannot make available any work that is in copyright and in print whose copyright owner is known without express permission from the owner. That’s why the Book Registry needed to be established.

The revised version did much to address the foreign author problems (after much noise was made by several foreign governments).

But are you sure on the opt-out question? As I recall, if one didn’t opt out of the settlement before a certain date, one was automatically included in the terms. Has that changed? I hadn’t read anything about the settlement suddenly becoming opt-in (except for orphaned works). I know the company I work for certainly had to opt out because had we taken no action (or been unaware of the settlement) Google would have been granted the right to include our books in their business.

Here’s where I’m confused. Inclusion is still strictly “opt out”. Display of full contents, if under copyright is “opt in”:

http://bit.ly/aF3QWZ

G to determine if book is commercially available (i.e., in print) or not (out-of-print)

• •

If in-print, default is no-display of contents – © owner must opt in to display uses – Most in-print © owners likely to sign up for GPP

If OOP, default is G can make display uses (including all commercializations)

– Display of up to 20% of contents for preview uses – But BRR-registered © owner can opt out, insist on no-display

– Arbitration process available if dispute over in- or OOP • © owner can ask for removal of books from corpus

– But “remove” only means these books are dark-archived – Rights to remove will expire in 2011

There are different “opt out” requirements. Publishers had until May 5, 2009, to decide whether to opt out of the Settlement altogether. If they chose to remain within the Settlement, they further have until April 5, 2011, to notify Google if they wish to opt out of Google’s proposed “display uses” of books not in print. For all books in print, Google cannot make any display or access uses without the publisher opting in to them.

The errors in this database may be worth studying. For instance, “Internet” and “email” occur around 1900-1910, then disappear until later in the century. “iPad” and “iPhone” appear in the 1880s.

What was the OCR error rate? Apparently, not zero. What is an acceptable error rate for studying the history of language usage to postulate cultural conclusions? Should I conclude that a small group of time-travelers have been discovered?

I agree with Rick: there is no reassignment of copyright to Google anywhere in the Settlement. The proper way to characterize the agreement about orphans works is to say that Google is given a limitation on its liability for copying them. The Settlement really functions more like an insurance policy for Google than anything else.

Isn’t this just a semantic argument? No, the actual copyright isn’t transferred to Google. But the rights granted by the copyright, which can only be conferred by the copyright holder, are being offered exclusively to Google without the express permission of the copyright holder. Through the agreement, Google gains the right to copy, distribute, sell and (depending on your opinion) create derivative works from items for which they do not hold the copyright. That’s a grant of copyright in everything but name.

It’s also more than an insurance policy. An insurance policy assumes the rightsholder can eventually be found and lets Google off the hook for violating copyright. In many cases, the rightsholder will never be found, and Google is given exclusive access to exploiting the material.

I think it’s the issue of “exclusivity” that takes this beyond a semantic issue. If the settlement does assign to Google the exclusive right to use orphaned works as if it held copyright in those works, then you’re right — Google has been given copyright for all meaningful purposes. But I’m pretty sure the settlement doesn’t actually do that (again: please correct me with a citation if I’m wrong). I think it gives Google rights, but not exclusive ones, and in copyright it’s exclusivity that matters. If only one person has the right to make and distribute copies, etc., then that person has copyright; if everyone in the world has those rights, then no one has copyright.

The settlement doesn’t apply to anyone else, just Google. They get those rights. As the Justice Department notes, the revised settlement does go some way toward taking away Google’s complete exclusivity by including a provision forcing Google to license the library to competing services, but it still grants them a practical monopoly on the market:

“The department also said that the amended settlement agreement still confers significant and possibly anticompetitive advantages on Google as a single entity, thereby enabling the company to be the only competitor in the digital marketplace with the rights to distribute and otherwise exploit a vast array of works in multiple formats.”

That’s why companies like Microsoft, who had their own book scanning project going, and Amazon oppose it so strongly.

That’s a very important point in regulatory terms, but there’s also a very important legal difference between “significant and possibly anticompetitive advantages” and copyright. You’re right that the settlement doesn’t apply to anyone other than the parties to the settlement, but that’s exactly the point I was making at the outset: the settlement doesn’t overturn any laws; copyright law doesn’t change in any way as a result of the settlement.

I guess that’s why I feel like we’re arguing semantics. It doesn’t overturn copyright law, except in the case of one company for an enormous number of published works. It basically creates an exception to a law without the input of Congress.

Don’t get me wrong, I think access to the treasure chest of orphan works is wonderful thing. I just want them put in the public domain by law, not given to private companies for the purpose of profit through backroom dealing.

I have a quick question about opt-in vs. opt-out and class action suits generally. Every so often I find myself assigned to a class in the event of a lawsuit — maybe because I bought a car that turned out to have something wrong with it, or I used a prescription drug that turned out to cause measles, or whatever. Sometimes I see invitations on TV: “If you’ve used Drug X, you may be entitled to a cash settlement; call this number blah blah blah.” That’s pretty clearly an opt-in situation. However, I seem to recall that I’ve also received mailings telling me that I’m automatically part of the class unless I actively opt out. Am I mistaken in my recollection? Or is it true that opt-out arrangements are considered routinely acceptable in class action lawsuits?

According to Wikipedia (trust at your own risk) that is correct:

“A major revision of the FRCP in 1966 radically transformed Rule 23, made the opt-out class action the standard option, and gave birth to the modern class action. Entire treatises have been written since to summarize the huge mass of law that sprung up from the 1966 revision of Rule 23.[20] Just as medieval group litigation bound all members of the group regardless of whether they all actually appeared in court, the modern class action binds all members of the class, with the exception of those who appear and object.”

The question isn’t whether this is out of the ordinary, the question is whether this is the appropriate forum for the offering. As the Justice Department puts it, the settlement goes way beyond the causes of the lawsuit (does Google have the right to scan books?) and instead uses the process to create a new profit-making opportunity:

“…the amended settlement agreement suffers from the same core problem as the original agreement: it is an attempt to use the class action mechanism to implement forward-looking business arrangements that go far beyond the dispute before the court in this litigation.”

The exclusivity that the Settlement grants Google is not in relation to copyright ownership but to the limitation on legal liability, which protects Google from being sued for infringement of orphan works as any other company entering this business would still be subject to.

Right. Google is not given copyright ownership, but is exclusively granted most of the rights copyright offers. Where it gets into semantics is whether you consider giving one individual (or corporation) a blanket exemption from the consequences of an existing law to be a change in that law. The closest equivalent I can think of is diplomatic immunity, but that is granted through international law and treaty, not through a private settlement between private companies in a civil suit.