Editor’s Note: This post, published almost exactly one year ago, has stuck in my mind as one that bears revisiting. I keep seeing echoes of this thinking, but without the self-consciousness I’d expect in today’s media world.

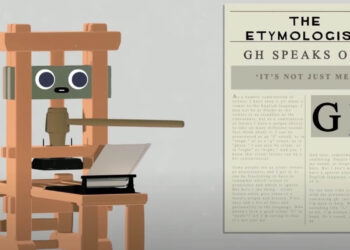

If you’re familiar with publishing, then you’re familiar with the challenges facing traditional publishers to move from being print-focused to content-focused, thereby enabling the delivery of content through multiple output channels (print, online, phone, tablet, etc.).

To be content-focused, content developers must first consider the utility or customer use being addressed by the content and only after that determine the most effective delivery mode (print, online, mobile) and packaging option (book, article, app).

But what happens instead is that print, having been the only mode of content delivery for so long, has become the mode of content creation as well. Publishers create content for print.

When other modes of content delivery and distribution became prevalent, print became the input to those modes.

If the creative process is predicated on print, then all other outputs are a post-process that occurs after content is ready for print.

Why is this a problem?

- Print is slow. Many publishers are waiting until they have final print pages before they start other product types. This includes finishing steps that are solely related to the appearance of the content in print and add no value to its existence in any other form.

- Print is limiting. By focusing the content creation process on print, publishers are not always considering how to best present content in other forms, fully taking advantage of the capabilities those forms and delivery mechanisms introduce. Instead of considering the content and its mission up front in the creation process (i.e., What user/customer need is the content intended to address? How can it best do so?), only the “print mission” is taken into account.

- Print is inflexible. Being inflexible means that, by being limited, you’ve introduced immovable (or burdensome) constraints to your content. For example, the thought process becomes “How can I make this two-dimensional table more interactive?” rather than “What is the best way to communicate this data to the customer?” In the former example the content creator will incrementally innovate on the baseline “table” standard instead of starting with the customer need and considering the best presentation method. Radical new forms rarely come out of incremental innovation.

- Digital is in demand. Customers increasingly rely on digital sources for information. To many, print has become the adjunct. By maintaining a cultural center around print, publishers continue to miss new opportunities for their content and instead provide space for non-publishers to fill those customer needs.

Perhaps the most disturbing issue with print becoming an input is that content creators are not always aware of how deeply print requirements have become embedded in their thought processes. It’s almost impossible for some publishers and editors to envision content separate from presentation (delivery mode and/or package). This situation leads to a cultural rift when content-centric thinkers naturally evolve at, or are hired by, print-centric organizations. They can meet with great organizational resistance.

One primary source of resistance is that print-focused staff, and the processess that have evolved over centuries to support print, focus on print’s immutable nature. Near perfection is required prior to distributing printed content. While no one advocates that quality be thrown to the wind in other delivery modes, the measures of quality, the culture of correction and discussion, and the ability to change content even after it has been distributed, all contribute to a different definition of quality in non-print modes.

This is further complicated by the fact that print is usually the primary contributor to revenue, although print revenue is often flat or marginally shrinking. Experimentation with new content thinking and delivery forms produces only a small fraction of print revenue (if the experimentation yields any revenue at all in the short-term). In addition, there are often no rules or established business models to guide product development. Since it can be hard for advocates to garner resources, content focused projects are often pushed off the radar or into skunk works — contributing even more to an “us versus them” mentality.

Hence the cultural divide. Neither side is wrong in their own context. They’re simply speaking different languages and value different things. Unfortunately, each is also attempting to apply their language and practices to the other, judging each other’s value with the wrong measuring stick.

But since print has become an input, it has a lot more muscle than it should. Other potential content products inherit print’s DNA and can’t help looking like their parents.

There are many ways to break this cycle, but none of them are easy. They take a combination of leadership, education, experimentation, and, in some cases, trial separation. But we need to remember that this isn’t about print versus digital. It’s about content and flexibility. It’s about the evolution of customer preferences and expectations.

The issue isn’t which output formats will win. The issue is will we, as publishers, be able to produce content in the ways in which our readers require and desire it?

Discussion

3 Thoughts on "Stick to Your Ribs: When Did Print Become an Input?"

Well before this post was written, the Gutenberg-e project was launched to experiment with a new kind of scholarly document that had no strict counterpart in print. The result? The market–meaning professional journals that review new books in the field–would not accept this product and insisted on seeing something in print, even if it was only a partial reproduction of the online content. It’s not surprising that, in light of such market feedback, publishers are leery of doing what Ann Michael recommends, which on the face of it sounds reasonable enough.

My mother–really–once told me in response to who remembers what question–that it all comes down to economics. Some publishers miss the boat on economics, but part of the reason different aspects of the publishing industry tip quickly and others incrementally, does have to do with economics. Who has the tech, who markets to the tech, development costs, development and invest vs loss or gain of market share. Sometimes the answers look simple and are simple or turn out to be simple–other times not. Learning curve with anything new. Some things more predictable than others–but there is always a big picture and it is true that new developments can also be held back for reasons that are not reasonable. Thanks for reposting. I like to see our thinking and doing in retrospect since this field is still spinning.