If you are a fan of academic banter and hang out on Twitter, there are several irreverent Twitter handles you can follow to get a glimpse into the world of academics. A few of these center around peer review. Handles such as @yourpapersucks or @academicssay deliver fictional and sometimes real and frustrating examples of less than helpful feedback given to authors. Many of these are comedy gold.

Recently, Twitter brought to light the opposite end of the spectrum when two female authors complained about receiving the review comments that follow:

“It would probably also be beneficial to find one or two male biologists to work with (or at least obtain internal peer review from, but better yet as active co-authors), in order to serve as a possible check against interpretations that may sometimes be drifting too far away from empirical evidence into ideologically biased assumptions.”

The authors did not name the journal but with help from the internet sleuths of the world, we learned that the paper was reviewed for PLOS ONE.

As someone who is responsible for overseeing peer review, two immediate thoughts popped into my head: “How could the journal let this happen?” And, “Thank god it wasn’t one of my journals.”

This story hasn’t exactly gone unnoticed and much has been written about it but I think it’s worth unpacking a bit here in the Kitchen.

Added to the list of 82 things publishers of journals do, one responsibility should be to foster a constructive forum for authors to present their work. There is no shortage of blog posts and editorials about why publishers are superfluous to the academic publishing process. Some argue that review by peers can be done outside of any formal system and in fact, there are several new ventures that are trying this out.

There is a problem, however, when “editors” are removed from the process. Editors have a responsibility to ensure that reviewer comments are constructive and free from personal attacks. Suggesting that two female authors add a male author in order to improve the paper is a personal attack.

It really makes no difference whether the paper was good or significantly flawed. The reviewer may have been completely correct in stating that the paper lacked empirical evidence. Why on earth the reviewer thought it was appropriate to suggest that the way to solve this would be to add a male co-author is where the train goes off the track.

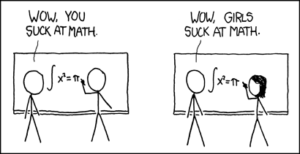

This is obviously not the first time sexist comments have been made by reviewers. More often than not, the biases appear to be more subtle. Many studies have been done showing the disproportionate number of papers accepted with male authors as opposed to female authors. Further, editorial boards are often lopsided. Conferences are male dominated. Women have been advised to only include first initials so that their gender is not obvious to reviewers. Gender bias is one of many arguments for double-blind peer review and for open peer review.

So back to my two initial reactions, the “how could the journal let this happen” question takes on a new flavor when you take into account that the journal was PLOS ONE. PLOS ONE employs a process whereby papers are reviewed only for technical merit. Additionally, the editorial hierarchy lacks the same kind of oversight seen at many journals. After a paper passes the initial sanity test, an Academic Editor is assigned. This person has sole oversight of the paper. The academic editor (of which there are over 6,000) decides whether to accept or reject the paper and decides whether to get an additional review. In this case, the academic editor solicited a review, got it, and either agreed with it or didn’t read it and rejected the paper. There is no editor-in-chief nor is there any indication that PLOS ONE staff review the decisions and author letters.

Authors who feel as though a rejected paper was not given a fair review can appeal the decision. There is very little information about what this process entails on the PLOS ONE site.

This leads me to my second reaction, “thank god it wasn’t us.” The truth is, this could have (and probably has) happened to a lot of good journals. Everyone is under pressure to speed things up. Big increases in submissions are putting pressure on volunteer editors. Anyone who has ever managed a journal knows that some handling editors are awesome and some are, well, not. It’s that second group that makes us nervous.

In a more traditional journal review process, there is an editor-in-chief and maybe subeditors (associate editors or section editors) who are tasked with oversight of peer review. The levels present on an editorial board vary depending on the size of the journal and the discipline. In many cases that I am aware of, journals staff also review every decision letter before it goes out to the authors.

I have always expected that the editorial coordinators on my team will take a close look at the reviewer comments before sending them to the author. The coordinators should look for whether the reviewer has accidentally identified themselves (which may or may not be a problem depending on your peer review policy), that the review appears to be for the correct paper (mistakes like this happen all too often), that the reviewer isn’t requesting that the author cite the entire publishing history of the reviewer, and that inflammatory language is never included. There are a dozen reasons that a coordinator could miss comments such as were made in the PLOS ONE review– being interrupted by an author calling for an update on her paper, trying to catch up on decisions that stacked up during a vacation day, not being on the top of one’s game when skimming through dozens of reviews that are technical in nature, etc.

This recent incident at PLOS ONE has afforded us a teaching moment. The scholarly publication process is a human process. People make mistakes, people say dumb things and some people are just jerks. As journal publishers and journal editors, we have a responsibility to protect our authors from the jerks. To be clear, it is okay to tell an author that the paper has serious problems. It is not okay to tell the authors that their fatal flaw is their gender.

As publishers, we also have a responsibility to correct these mistakes, as I believe PLOS ONE has done, albeit a bit slower than the authors may have liked. The authors took their complaints to Twitter after having not gotten a satisfactory response to their appeal request within three weeks. I can’t imagine what took so long. The social media storm that ensued moved things along and PLOS then dismissed the reviewer and removed the review from the system. The “academic editor” who handled the paper has been asked to step down and the paper is being given a new review. All of these individuals remain unidentified.

Issues facing women in academia and scholarly publishing are sadly a reality. Much of the gender bias in the publishing side could be eliminated by diversifying editorial boards, diversifying reviewer pools, zero-tolerance policies against gender bias in review, and review processes that protect authors from unfair treatment (going totally dark with double-blind review or shedding light on all participants with open review).

Journals have witnessed a series of peer review crimes lately—faked reviews, made up papers, papers authored by Maggie Simpson. While these incidents are serious and a black mark on the journal peer review process, they represent clear cut, black and white issues. Gender discrimination in academia and society at large is far more insidious and harder to root out. Hopefully some good will come out of this incident and the resulting raised awareness for editors and reviewers will lead to greater care and scrutiny in the future.

Discussion

24 Thoughts on "Sexism in Peer Review"

There is no accounting for jerks! Unless the “jerkness” has been revealed previous to being a reviewer than one cannot know that a reviewer is a jerk!

Angela, this is a such a huge, and hugely important, set of issues. I’m so glad you raised them so thoughtfully. I’m particularly interested in the way that anonymity works. In all kinds of forums–social media and teaching evaluations are two obvious places to start–anonymity seems to either encourage or allow sexist expression. But as you note, double-blind peer review, the anonymity of all parties, helps mitigate the sexism that so much research has shown attaches to female names (school and job applications, publication etc.). I’m leery of crowd-source peer review and post-publication review for lots of reasons, but the combination of bias in social media and in professional evaluation is among them.

I was about to post a similar reply–thank you for wording it so elegantly. This is a question I’ve gotten from female students who are considering publication and it grieves me that I have to tell them that yes, they are better off using an initial. How is it possible that so many people find it difficult to accept that women are more than a uterus.

I think there is not much that can be done except for naming and shaming the twisted mind that did this. A lot of focus has shifted to PLOS, I wonder if that’s right, for all we know he might be doing the same for all the Journals at every such manuscript he reviews. Presently the responsibility lies with PLOS to not let the reviewer get away with this

Betraying the confidentiality of the peer review process is a slippery slope. You may feel it is justified here, but what about the next situation where someone says something you disagree with? What if someone is unduly harsh toward your next paper? Should that person’s identity be outed as well?

A while back one of the founders of PeerJ was incensed that Michael Eisen received a negative peer review for a grant application that included comments that he spent too much time blogging instead of doing research. He publicly called for a witch hunt, for the community to find the identity of that reviewer and block that person from participating further in academic activities. Nearly every response was (correctly in my opinion) that doing this was an abuse of the sanctity of the anonymous peer review process and that it would have a chilling effect on reviewers’ ability to speak freely.

Either the process is anonymous or it’s not. You can’t pick and choose where you’re going to follow through on your promises and where you’re going to go back on your word.

There have been a number of metaphors used to explain this (e.g. one bad apple), or arguments about scale (e.g. with so many papers…); however, none of them have gotten so precisely to the point as your post. I don’t see this as an issue of sexism, per se, but what happens when responsibility and accountability are decoupled, as often takes place when you transform a cottage-style publishing model into an industrial one. Reputation is a fragile asset. While tens of thousands of PLOSONE authors may have had a satisfactory experience, it just takes one salient event like this to do remarkable damage to the publishers’ reputation. At this point, PLOS really has no other option than to ride out the storm, work (and pray) that it never happens again.

Good point, Phil. It’s challenging, but an EIC must exercise constant vigilance. I managed 2,000 reviews during my long tenure as EIC, and one of my worst fears was inadvertently letting a reviewer comment like this one pass through. Fortunately, our reviewers seemed fairly enlightened on the sexism issue, though I caught more than one inane comment on other matters. (I don’t think any dumb sexist remarks got through, or at least nobody told me!)

Reviewers will invariably make dumb and inappropriate comments. Every manuscript deserves the EIC’s attention, even if you’re busy, having a bad day, on travel, etc. You owe it to the authors and your readers. Your journal’s reputation depends upon your alertness. If you’re not willing to suck it up and pay attention to everything, you should not be an EIC.

Angela Cochran’s remarks on peer review, especially in her last paragraph, seem very well taken. The reviewer whose comments touched off this particular storm probably thought he/she was being helpful and may very well be distressed to be placed in the same camp as the creepy guy who hangs around the office water cooler. My own experience in the academy comes from the history of science and medicine, which are interdisciplinary and have undergone a revolution in the past decade or two. A well-organized group of women and men are shifting research and publishing from what the late Roy Porter used to call the ‘pedigree of Truth’ into new and exciting realms of inquiry, incorporating complexity, less-heard-voices, and a global outlook. One need only look at the programs of the annual meetings of the History of Science Society or the American Association of the History of Medicine to see how the field has become more diverse and of greater importance to the wider world of learning.

The humanities and some social sciences, of course, have the advantage of relying by and large on learned societies and on university faculties for their support. Mechanisms within these institutions already exist and can be exploited to level the playing field for less-represented groups and to educate or exclude those who bring personal bias into the academic arena. The system isn’t always successful, but it does provide a time-tested model for redress.

The Open Access movement not only opens exciting possibilities for every field, but it also exposes a number of difficulties that need discussion. Most obvious to me at least, are the unexamined problems in the sciences brought about by the increasing concentration of power in the hands of a few major research funders. The distinction between who gets funding and who gets published is disappearing. What does this mean for the quality of scientific research and for the incorporation of ‘outsiders’ into the disciplines. Great ideas don’t always come from the outer edges of a field, but they often do. How can one get work published if one can’t pony up for a fee in an important journal? Researchers from less-developed countries may be excluded, as will others. This isn’t a problem without solutions, but bias in funding and publication are almost inseparable and demand treatment.

A related issue is of Open Peer Review. An underlying model for this has existed in mathematics (for example), which has relied on a sort of blogging about difficult questions for decades if not centuries. Mathematicians seem a thick-skinned lot, and are shielded from public scrutiny by the fact that hardly anybody else understands what they’re talking about. Also, perhaps naively, I assume it’s easy in the end to decide who’s right. Open Peer Review takes many forms, but whatever form it takes, another system of redress will thunder in, and that is the law. Some publishers already know about this, as do book reviewers, and OPR may create more problems than it solves. Internet trolling and anonymous blogging are infecting the computer screens of female scholars and journalists especially. How will the field defend the vulnerable?

I have used the term ‘adult supervision’ elsewhere in other comments, and would like to repeat it here. If the OA movement in all its forms does not act to empower the vulnerable and to redress grievances, the law will and it won’t be pleasant or cheap. Too much is at stake. Funding universities, libraries, and academic publishers is a proven method, and a good editor is a pearl of great price.

“If the OA movement in all its forms does not act to empower the vulnerable and to redress grievances, the law will and it won’t be pleasant or cheap. Too much is at stake. Funding universities, libraries, and academic publishers is a proven method, and a good editor is a pearl of great price.”

This comment is very important. I ask these questions a lot. These are the “okay, but what happens when…” questions that some of these new initiatives ignore or figure they will deal with if they ever come up. I can only guess that this happens because they don’t engage any naysayers in the development process. Every new and radical change deserves the “devil’s advocate” asking about the what ifs.

The vertical integration of academic publishing and funding is happening almost without discussion and often covertly. How many referees will be happy to be exposed to litigation from an aggrieved author or authors? Fewer and fewer, until, perhaps, every decision is in-house. We need to hear more voices, not fewer, and dissent should not be silenced by charges of being ‘opposed to change’. Reductionism not pluralism is the failed way of the past. We can all think of examples.

This approach is a big problem found in many initiatives aimed at changing scholarly communication. Rather than taking an evidence-based approach and working incrementally toward finding the right solution, so many policies seem to pull the specifics of their requirements out of thin air (embargo periods as an example). A policy based on the notion that we may very well break the entire system of research communication, but we’ll try to fix it again after we’ve destroyed it is a poor policy.

How/why did the reviewer know that the authors were female?

An Alternative to ensuring anonymity at every stage (which is hard to do completely) is to have fully open peer review, with all names and affiliations open to all from the start. And those who don’t want to take part in it, well, just keep quiet.

Maintaining the formal structure of anonymity, even if it is sometimes impossible to maintain in reality, has a function. If the reviewer in question was forced to write as if he did not know the identity of the authors, he would not be able to make the comment he did, since he would have to presume that the authors could have been either male or female (or both).

There are pluses and minuses to open peer review. As you note, it adds accountability–don’t say anything you aren’t willing to say publicly. Reports from those journals using open peer review are that they get better-written reviews, and reviewers spend more time on them (likely because they know they will be read by many).

The downside is the potential chilling effect on free speech, and a loss of the ability to speak truth to power. If I’m asked to review a deeply flawed paper by someone powerful in my field, I may not feel comfortable speaking honestly about the work if I’m identified as it may result in retribution taken against me. Where journals give reviewers the choice to sign their names to their reviews, the numbers show that many are willing to sign positive reviews but very few are willing to put their names on negative reviews.

We presume that reviewers wouldn’t be openly sexist. Yet the research shows over and over that reviewers (whether for job or school applications, for publications, for funding) reward male over female time and again. A reviewer might not openly say “gee, get a man on the job to help you out, sweetheart,” but the stats suggest that their bias will nonetheless work against the female researcher/ author.

Depends on what you mean “from the start”? A drawback with pre-publication open peer review is that authors’ oversights are immediately exposed to broad audience and rejection is a matter of public record. Traditional peer review offers a private space for collaboration between authors, reviewers and editors before a manuscript is published; and rejection remains a private matter allowing the author to course correct before going public.

I witnessed gender bias of a different sort in the review of a book manuscript at a top university press in the early 1980s. The book was about different types of feminist approaches (liberal, Marxist, etc.), and as acquiring editor I had it reviewed by two scholars who are feminists representing two of the different approaches. But their reviews were so positive that the press’s faculty editorial board consisting entirely of men suspected bias by the reviewers supporting a fellow feminist. So the board asked me to get another reader known to the faculty because she was at the press’s home university. Her report was more moderately favorable, but the board voted against publishing the book anyway. It went on to become a classic in the field, and the author herself became a leading feminist scholar over time.

Interesting story, Sandy. Even in my grad. seminars we have to work through why students think that feminism is an overly political (and suspect) commitment for a scholar. Why is being staunchly opposed to sexism suspect, when being staunchly opposed to racism or any other form of discrimination isn’t? It’s always a very interesting discussion.

Science has a closely related editorial today: “Give women an even chance”

http://www.sciencemag.org/content/348/6235/611.full?utm_campaign=email-sci-toc&utm_src=email

This is a fascinating problem, because the behaviors in question are often deeply entrenched, to the point of being linguistic. My wife says she can tell the sex of the person I am talking to on the phone, just from the way I talk, perhaps just from the tone of my voice (whatever that means). Changing this would not be easy. No reason not to try though.