PubMed Central (PMC), a digital archive of biomedical articles, increases the citation impact of deposited papers, a recent study suggests.

The paper, “Examining the Impact of the National Institutes of Health Public Access Policy on the Citation Rates of Journal Articles” was published October 8 in PLOS ONE. Its lead author, Sandra De Groote, is a Professor & Scholarly Communications Librarian at the University of Illinois, Chicago.

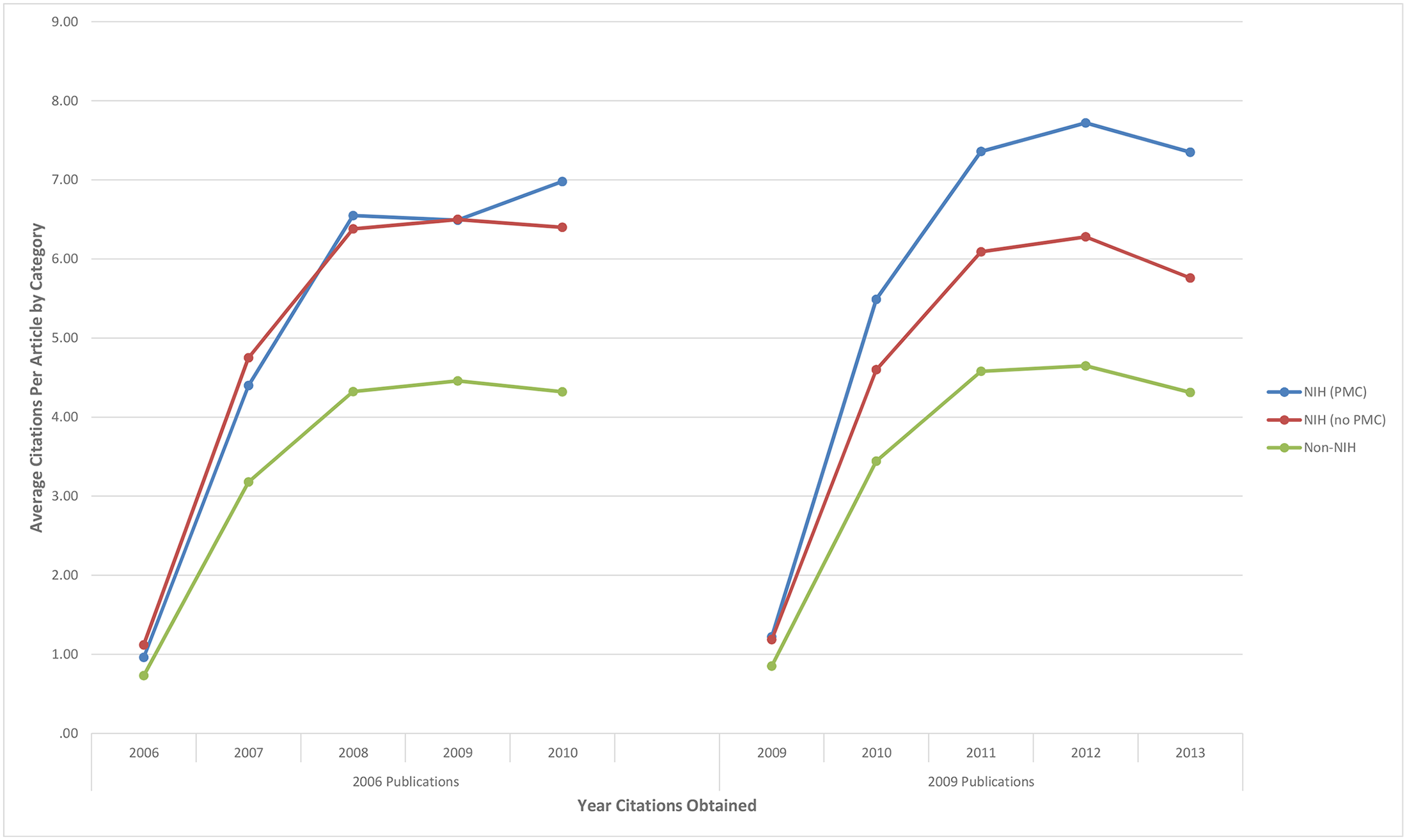

De Groote and her colleagues were interested in measuring what effect, if any, PMC has had on the distribution of NIH-funded papers. As the NIH Public Access Policy, requiring mandatory PMC deposit, took effect in 2008, De Groote focused on two cohorts of papers: those published in 2006, when deposit was still voluntary, and 2009 after deposit became mandatory. We should note that just 9% of 2006 NIH-funded papers were deposited in PMC compared to 72% in 2009. It is not known whether these deposits were made by the author, the publisher, and in what format (author’s final manuscript vs. published XML).

The researchers excluded from their analysis all Open Access journals as well as journals that make their content freely available after an embargo period. Their dataset includes a total of 45,716 papers appearing in 122 biomedical journals.

De Groote reports that while there was no overall difference in the performances of 2006 papers, 2009 papers deposited in PMC were cited 26% more frequently over 5 years, a difference of 5.2 citations per paper, on average.

The researchers noted that there were differences in the composition of the papers in their cohorts, specifically in the journals appearing in each group as well as the number of authors per paper. While they tested for these differences, they did not report their adjusted results. Thankfully the authors deposited their dataset, which allowed me to verify their findings and to provide more nuance.

I appreciate the effort that went into gathering and analyzing this paper; however, I feel that it suffers from three major weaknesses that may undermine the validity of its claims:

1. A statistical model that fails to fit the data. The researchers used a statistical model that assumed their citation distribution was normal instead of skewed–a feature of most citation distributions. As a result, a few highly cited papers in the PMC group inflated their reported difference. Using a non-linear (Poisson) model on their dataset, I arrived at an unadjusted difference of 22% (95% CI 20%–23%), 4 percentage points lower than De Groote’s claim.

2. An inability to control for confounding effects. Papers published in some journals perform differently than others (for example, compare the papers published in The Lancet with a specialized nursing journal). If we simply add the journal information to the regression model, the main effect drops from 22% to 16%. This 6-point drop tells us that that papers appearing in higher-performing journals are more likely to be found in PMC than the control (non-PMC) group. Similarly, if I add the number of authors per paper to the regression model, the PMC effect drops another point to 15%, again suggesting that the a simple comparison of PMC vs. non-PMC papers is not going to provide the researcher with an independent, unbiased estimate. Or put differently, their reported PMC effect is confounded with other citation effects.

3. A dataset contaminated with non-research papers. While the researchers claimed that their study was limited to research articles, this is not supported by their dataset. With just a few minutes of spot-checking, I came up with a letter to the editor, an introduction to a special issue, several perspectives, commentaries, and reviews, a point/counterpoint, and a lecture. Unless an equal number of these non-research papers are found in each cohort–which is pretty unlikely–the main results of this study are likely to be biased.

Personally, I’m surprised that the PLOS editor (a leader in bibliometric research) didn’t catch any of these problems. The paper is clearly too methodologically weak to be considered “sound science.”

As a result, it is difficult to interpret the results of this paper. Did PMC really improve the citation performance of NIH-funded papers, or is PMC composed of papers that generally perform better? While the researchers attempted to answer a very difficult question, they simply weren’t careful enough in the process. At best, De Groote’s estimates are overinflated; at worse, they’re making a false claim.

Federal policies based on funding sources are likely to create heterogeneous groups. Add that the NIH deposit requirement was adhered by less than three-quarters (72%) of 2009 authors, and it would be safe to assume that the comparison groups are not comparable. I reported recently on a similar control group problem with the Academia.edu citation boost paper. For retrospective observational research, the researchers should have assumed, a priori, that their groups were unequal and attempted to convince us otherwise, not the reverse.

Where does this leave us? There has been little empirical work on the effect of publicly accessible repositories, meaning that this paper, despite its methodological and analytical weaknesses, will have an outsized effect on steering public policy. And if we consider the paper’s conclusion, advocacy may be part of the authors’ intention:

This study illustrates a positive impact of the 2008 NIH Public Access Policy. Articles that are openly accessible in PubMed Central are often cited more than articles published in the same journals, but not openly accessible. This increase in scholarly impact is important to researchers and their institutions, to NIH, and to the public. This is a strong argument for expanding legislation to other federal agencies making information more accessible.

Rather than conclude on a negative note, I want to try something constructive. If you were to measure the effect of PMC (or the NIH Public Access Policy) on journal articles, how would you do it? Can the data, methods, and analysis of this paper be tweaked to get us closer to the “truth?” If so, what would you suggest?

Fortunately, this blog attracts a number of thoughtful and analytical minds. Together, perhaps we could get a little closer to answering a really important question.

Discussion

36 Thoughts on "PubMed Central Boosts Citations, Study Claims"

You might try taking a set of journals with a relatively low fraction of NIH related and PMC published articles, then compare the citation rates of the PMC published articles to those not found in PMC.

But given the complexity of the research system thie question may not be answerable. For example, NIH may simply fund more highly cited research.

I agree that the researchers could have stratified their dataset and conducted some internal validation, for example, by comparing high-impact journals to low-impact journals; or multidisciplinary journals to specialized journals; or journals in which the majority of papers are sponsored by NIH compared to journals in which only a minority of papers are NIH-sponsored. As a control, using HHMI or Wellcome Trust (which have their own policies) could help determine the cause of the effect. Without these internal comparisons, we have a problem inferring cause and direction of the causation.

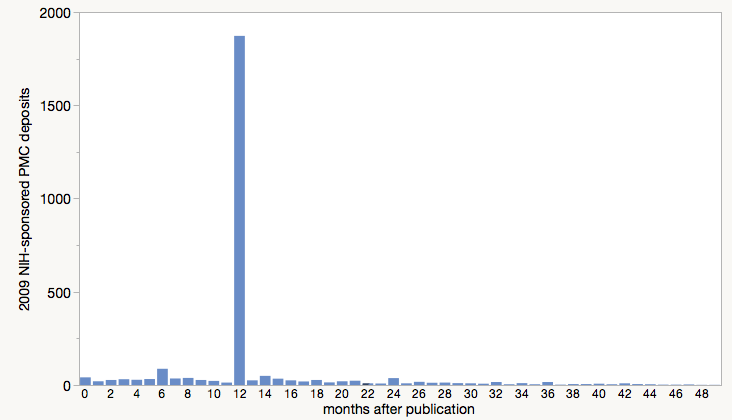

The De Groote dataset also includes a variable that calculated the number of months that elapsed between publication and PMC deposit. There is a big spike at exactly 12 months (68% of 2009 papers), suggesting that these are publisher-deposited papers, while the others are author-deposited. Excluding the spike at 12-months, one could examine whether the citation effect declines as the delay between publication and deposit lengthens. If PMC indeed has an effect, it should diminish as the delay grows.

We are seeing more and more “research” papers that are thinly veiled pieces of advocacy. Either the authors of these articles know little about the scientific method and the correct application of experimental controls, or they are driven to make a political point and the experiment is set up to provide the answer that the author wants in order to make their point. I see lots of this in bibliometric studies around access and impact of research articles. Either we have a poorly trained generation of bibliometricians or even-handed analysis is not the goal (http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2015/07/20/advocacy-analysis-and-the-vital-importance-of-discriminating-between-them/). PLOS ONE has clearly failed in applying the rigor they so often tout in their peer review process. If the conclusion of the study is a plea to change governmental policy to how the authors think things “should” be, then the article should be accurately labeled as an editorial, not a research paper.

One way to improve the analysis would be to control for funding sources on the papers in both experimental populations. NIH funding is highly selective–only a small percentage of those who apply are deemed worthy of such grants.If one population of papers (those in PMC) have passed that hurdle, while the other (those not in PMC) hasn’t, then you are dealing with two qualitatively different samples. Perhaps the conclusion here should be that the NIH is really good at funding studies that are likely to be cited, rather than any effect of impact.

Ideally you’d want to compare papers in PMC with NIH funding to a cohort of those with NIH funding that were not deposited, in order to keep things equal.

David, the main comparison reported in the paper is between NIH (PMC) versus NIH (no PMC) see Figure 1. However, there are lots of papers in which the author listed that he/she received NIH funding that were not research papers (perspectives, commentary, letters, etc). So I think the researchers could have gotten closer to a comparative sample by ensuring that their treatment and control groups were all original research papers. One way they could have done this, without looking up each paper individually, would be to exclude papers that were 2 pages or less and written by a single author.

Interesting article. Having worked at NLM for 10 years and after talking to key staff I would question the compliance rate and would be amazed if NLM is able to measure the the deposit level. I had heard the 2006 number was more in the 3% range and to climb to 72% by 2009 would be just short of a miracle. Seems to me there is more advocacy thinking in this article than real science. I would question the peer review process as well. The researcher should have taken a sample of papers to ensure that they were coded properly before the analysis. Too often is the case that poor research results becomes the foundation for the OA PR machine.

I tend to agree, Dan. In fact these compliance numbers are pretty strange. The FundRef drill has demonstrated that it is very hard to pin down the funders of articles, which PMC would have to know in order to generate these numbers. They would have to know exactly how many NIH related articles were published each year and that is not possible.

Two thoughts on how to improve the study (but not sure it could be done with the current dataset as a sort of “dry lab” analysis):

1. Some kind of randomized assignment of papers. By this I mean some way to control for or eliminate the potential bias that people are sure to put their best papers into the repository, those in the higher-impact journals, etc. (This was a theory behind the several studies that report an OA-citation advantage.)

2. Some by-journal analysis, so that the high-impact journals don’t swamp the lower-impact journals in the study. Or some other way to control for variable impact. Going back to selection bias above, if people deposit their articles in highest-impact journals, but not all papers, it could lead to a result such as the study shows.

It could be that there is an association between citations and depositing, but that could be explained by a selection bias, or causation.

I’m also puzzling over whether the embargo period (the time delay from publication to release of a paper in PMC) has some effect on this. In the typical impact formula (2014 citations to articles published in 2012 and 2013, e.g.), if an article is published in 2013, it (likely?) becomes visible in 2014. So the effect of PMC on JIF might be attenuated by the embargo period. (I realize that the paper isn’t focused on JIF, though.)

I appreciate that Phil’s got us all reviewing how to get to a reliable result. This is a topic that could lead publishers to change their deposit policies from laissez-faire to directed-deposit, and that should be on good evidence.

John

Regarding the embargo period, it appears that the overwhelming majority (68%) of NIH-sponsored papers became available in PMC exactly 12-months after publication, suggesting that publishers were responsible for depositing the published paper on behalf of their authors.

Forgive me, as I haven’t looked at the data, but why does this information lead you to the conclusion that publishers were doing most of the depositing? Or, more accurately, how is time of deposit defined in the data? Without knowing any better, the conclusion I would jump to is that the vast majority of deposits into PMC were made with a 12 month embargo, and that the data defines “deposit” as “date publicly available.”

For example, if I published a paper in Jan 2009, made my deposit into PMC in Jun 2009 (perhaps finalizing the deposit in Jul or Aug), and selected a 12 month embargo, my paper would be made public in PMC in Jan 2010. So would the data note my deposit date as Jun 2009 or Jan 2010?

Good point. Having worked with publishers, I know that many deposit in PMC on behalf of their authors. They are also very careful on selecting that the paper be available in PMC no earlier than 12-months after publication.

This post, based on results from a FOIA request, shows that a few years ago, 20% of articles coming into PMC were deposited by authors and 80% by publishers.

http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2013/07/16/the-price-of-posting-pubmed-central-spends-most-of-its-budget-handling-author-manuscripts/

I’m told that in a recent meeting with publishers, David Lipman from PMC used the numbers 75% and 25% (publishers/direct deposit from authors).

Though I agree with your conclusion that PMC articles may just be higher-performing, I was hoping you could elaborate a bit on a few of the points in your numbered list.

First, any way you could be more detailed about taking journal information and number of authors into account in point #2? I have a firm (if basic) understanding of statistics and I’m curious how this was done.

Second, I am inclined to disagree with you on point #3. I don’t see how we could assume that non-research items would mistakenly appear in one cohort and not in others or why they’d be appear in different proportions. In fact, after a bit of spot-checking of my own, I found an introduction and a lecture in the Non-NIH cohort and a lecture in the NIH (Non-PMC) cohort.

My comment included links to the articles, but it appears they have been removed. Here are the titles:

Introduction to special issue of neurobiology of learning and memory on habituation

Gabor Than Award Lecture 2008: Pre-eclampsia – From Placental Oxidative Stress to Maternal Endothelial Dysfunction

Angle-Closure Glaucoma-Simpler Answers to Complex Mechanisms: LXVI Edward Jackson Memorial Lecture

Hi clayton,

Regarding your first question, Journal is added to the regression model as a categorical variable. This is also known as “blocking.” With regard to your second question, based on the definitions provided by the NIH to determine applicability to the policy (see: http://publicaccess.nih.gov/determine-applicability.htm) papers that were written by an NIH-supported investigator that were not peer-reviewed or were not the result of “direct funding” would be in the NIH non-PMC group. As exemplified (commentary, perspective, point-counterpoint, lecture), these papers could have been classified by Scopus as “journal article” but are really not comparable to original research papers. Hence, the groups are non-comparable. I don’t believe that it is the onus of the reader to systematically review the control group. The researchers should have done this for us.

I am vaguely familiar with blocking but will refresh my memory. I was more curious about how you defined your journal variable, though. How did you define your categories, and how many journals fell into each?

As for the second part, I agree that the researchers should’ve been more careful in weeding out non-research articles, especially when a ctrl+f search of the .csv file finds several such articles fairly easily. I don’t know that I’d argue that it invalidates the findings put forth or that it would be of extreme concern all on its own, though.

Clayton, I’m not defining any journal category–these data are available in De Groote’s dataset. The number of authors is also there, which is also highly skewed and should be entered as a log-transformed continuous variable. (I suspect that De Groote ignored transforming the author numbers as well.) Please remember that I didn’t claim that De Groote’s paper is invalid, but highlighted some significant weaknesses in her methodology and analysis. As I wrote:

As a result, it is difficult to interpret the results of this paper. Did PMC really improve the citation performance of NIH-funded papers, or is PMC composed of papers that generally perform better? While the researchers attempted to answer a very difficult question, they simply weren’t careful enough in the process. At best, De Groote’s estimates are overinflated; at worse, they’re making a false claim.

Forgive me, I’m looking at the data set and its accompanying readme file and I don’t see any headings having to do with the type of journal that the articles appear in. I think this is a bit of a misunderstanding on my part, I had the impression that you were putting multiple journals into categories in your treatment.

The authors do comment on the correlation between number of authors and citation counts in the “Limitation” section; more information on how they evaluated this correlation may have been appropriate, but it does seem that the authors investigated it somewhat thoroughly.

And I do agree with you on the last point. I found it interesting that the “Conclusion” in the article’s Abstract was much weaker (and more in line with the comments you’ve made here) than the “Conclusion” in the article itself. Regardless, I had only meant to point out that your point #3 seemed much less problematic than the first two.

Hi Clayton. I didn’t have to classify their list of journal, only use the information in the regression model. In this case JOURNAL is a categorical variable that can take any of 122 values, while CITATIONS is continuous variable. One can add other variables to the model, such as AUTHOR NUMBER, also a continuous variable, which should be log-transformed. I’m willing to explain more but I’m not willing to turn the comment section into a primer on linear regression.

I agree that the authors include some comments in their Limitations section, but they merely admit to the fact that their comparison groups are not equal, which means their main PMC effect of 26% is not accurate. Librarians, publishers, OA advocates, and policy makers will see the main results in the Abstract and take it as a finding based on “sound science,” which I think I demonstrated in my post, is a tenuous claim. At least, De Groote’s findings are inflated; at worse, they are completely false.

Hi Dr Davis,

here, as in your post on the academia.edu study, you analyze the raw data to reveal things that are not apparent from the summary measures in the papers themselves. Having demonstrated the value of data sharing, will you now share the data from your controlled trial on open access and citations? I’m sure figshare would be delighted to have them.

Our paper, http://arxiv.org/pdf/0709.0896 , shows the same effect for arXiv (in 2007) as in the PMC study (compare the figures).

This paper shows clearly that papers deposited in arXiv are more heavily cited than those which are not, and that this effect has nothing to do with the papers being available via open access.

In the PMC case it seems likely that the paper is simply showing that NIH grant funded research is more heavily cited than research which has not received an NIH grant.

On a scholarly blog, I would hope that everyone who posts has actually read the original article, and carefully too.

Care to be a little more specific, Neil? Which details reflect a lack of careful reading?

I am primarily referring to people who are posting comments without having read the article under discussion. A formal reply to your comments will be placed on Plos One.

A basic and easy question, based on the existing data (in the authors’ spreadsheet), is whether the citation count differences between (NIH & PMC) and (NIH & not-PMC) and (not-NIH) persist journal by journal. That might not answer any questions about method, but it is good to know.

Maybe I should do that myself, except I’d be worried about misunderstanding the data (an open data problem), even though the spreadsheet looks very clear and easy to read.

The question of citation advantage is just difficult to answer.

Admittedly that PubMed Central “would” boost citations, citations themselves are not more than countable numbers, no more no less without real values beyond the apparent one, see http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08989621.2015.1127763

Citations are used for a wide array of impact assessments by the scientometric community, so they are very important.

Citations are rather ‘MISUSED’ by the scientometric community…’

The value of citation is overestimated. Citing or talking about, for example, Harry Botter does confer it any real impact!

A paper can be cited not because it is ‘important’ or ‘interesting’ but because it is published here or there, or because the author or journal is known, or because it is contested….or…or… etc.

Whether the results of this papers can be interpreted causally probably depends on whether the composition of papers published on PMC has changed over time (especially in terms of paper quality). On a related note, I have recently come across another interesting paper (http://josephstaudt.weebly.com/uploads/8/6/7/0/8670096/mandatingaccess.pdf) on the NIH mandate by Joseph Staudt, a graduate student in economics at Ohio State University. He looks at whether the NIH mandate changed the share of papers published in open access journals and concludes that “the mandate caused the typical NIH-supported article to be published in a journal that receives between 5 and 10 percent fewer citations per document over the previous two years”.