Roxanne Missingham at the Australian National University recently pointed me to a blog post sharing the results of a survey by the Library Publishing Advisory Committee of CAUL (the Council of Australian University Librarians). The survey sheds light on the “wide variety of practices and activity” that make up today’s library publishing scene in Australia and New Zealand. The key findings of the survey (to quote from Roxanne’s post) are:

Roxanne Missingham at the Australian National University recently pointed me to a blog post sharing the results of a survey by the Library Publishing Advisory Committee of CAUL (the Council of Australian University Librarians). The survey sheds light on the “wide variety of practices and activity” that make up today’s library publishing scene in Australia and New Zealand. The key findings of the survey (to quote from Roxanne’s post) are:

- One in four university libraries in Australia is publishing original scholarly works in some form (mostly journals)

- Most are available online and are open access

- The publications are read widely (over 3.4 million downloads this year) and internationally

- New skills and services have been developed that support innovative publishing and scholarly communication

- Australian university publishing undertaken by libraries is world leading in terms of new forms of publishing, reaching wide audiences and innovation in practice

My interest was caught by the section summarizing the strategic objectives noted by the responding institutions:

- Dissemination of scholarship

- Open access – increasingly underscored by university open access policies

- Increased visibility of the university and university “brand”

- Enhanced engagement with scholarly communication

- Compliance with dissemination requirements of funders.

It perhaps won’t come as a surprise that I particularly found myself thinking about the third of these — visibility and brand, in relation to universities and their presses. Strengthening the brand is a time-honored reaction to financial pressures and we see all around us the evidence of universities seeking to take a more comprehensive approach to measuring, monitoring and maximizing their reputation.

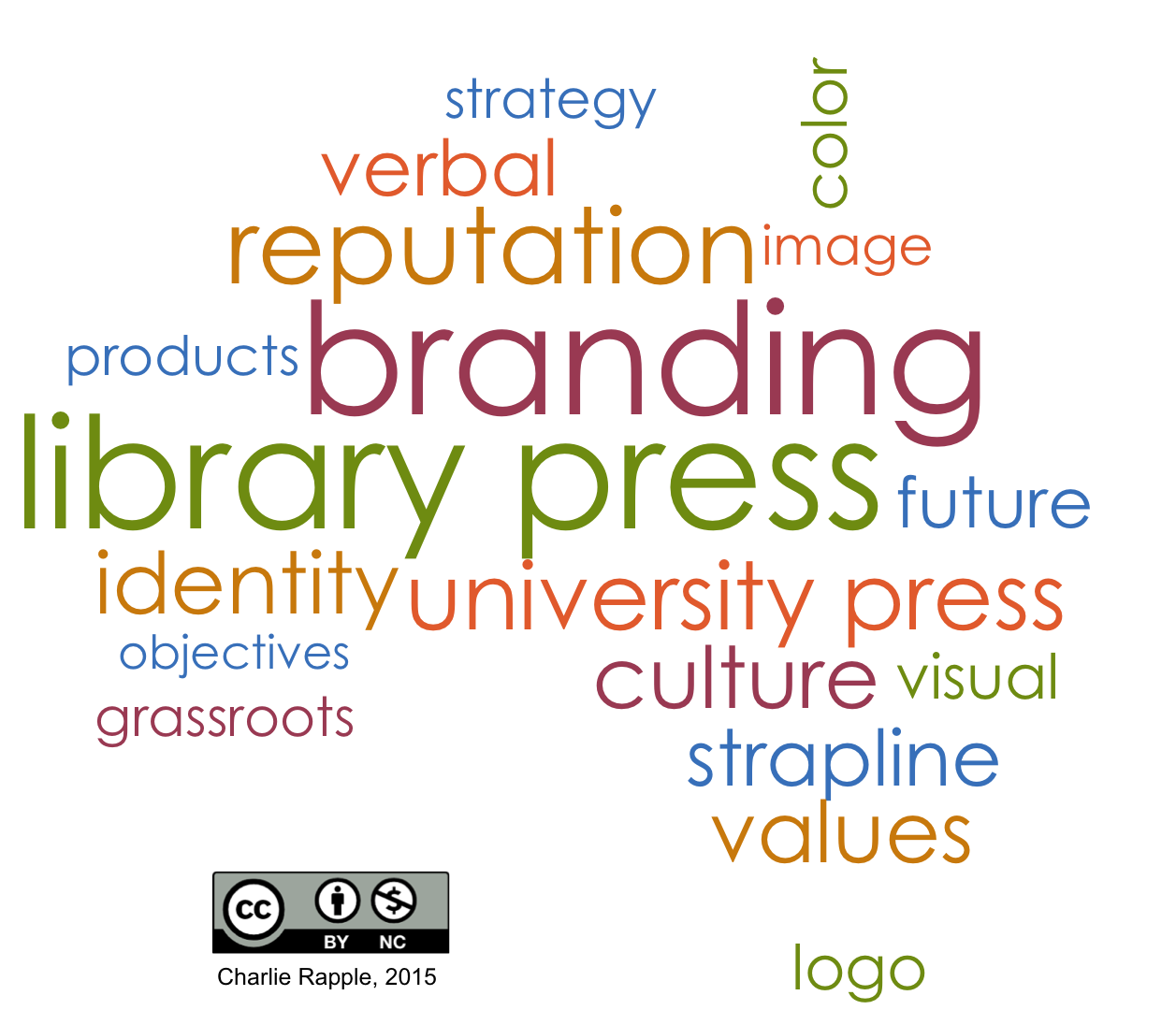

But — perhaps because Roxanne’s post moves onto other things, and because “brand” is such a nebulous word — I wanted to dig a bit more into the issues around brand and reputation for library presses. Since I found it useful to return to marketing theory as a context for my thinking, here’s a simplistic primer:

- Brand expression. This is what “brand” means to most people – the visual and verbal identity: logos (the etymological root), straplines, color palettes, product names and (to an extent) the products themselves.

- Brand idea. Effectively the organization’s internal motto. If the (external) strapline crystallizes an organization’s vision (the “what we are trying to achieve”), the (internal) brand idea distills the “how we achieve it” (so for example, at Kudos our strapline and vision is “Greater Research Impact” but our brand idea is “better understanding” — this provides a sort of strategic framework for our activities and a useful litmus test against which to test all aspects of what we do — will this proposed new feature give readers a better understanding of this piece of research? Does my response to this user query show my understanding of their problem? etc.)

- Brand values. The behaviors and characteristics you (a) recognize as already existing within the organization, shaping its success, and therefore (b) encourage / seek in your staff so that they embody the brand idea and convey a consistent brand identity.

- Brand image. What people think of your organization, i.e. your reputation — in part a result of all of your efforts above but ultimately influenced by many wider factors too.

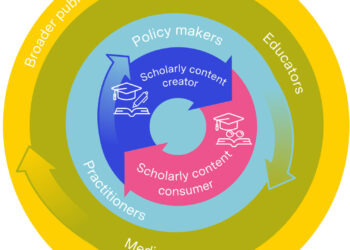

These aspects of brand theory are ranged along a spectrum, from the tangible to the intangible — and from those you can control (your visual identity), to those you can’t (your reputation). Most organizations have full control over those things in 1 and 2, and only begin to “lose control” in 3 and 4 (once the unpredictable behaviors and opinions of people — both internal and external — come into play). However, in pondering what the survey’s participants might have inferred in their use of “brand”, it struck me that library presses have less control over their brand ingredients than most. Presses that serve to publish the research outputs of their institution cannot make brand-oriented choices about their product; the range of research being undertaken within the institution, and therefore the range of material they will be asked to publish, may be so broad as to prevent the definition and building of a focused brand identity. Even if the strategic objective in the short term is to build the brand of the institution as a whole, it seems that most presses soon want to begin publishing work from authors in other institutions — Roxanne (in a separate email discussion with me) noted that increasing international participation is a goal for the Australian National University’s ANU Press, and that another relatively young, library-supported press at the University of Adelaide is already at the stage where over 70% of its authors are from other institutions.

This transition – from exclusively in-house press to publisher of a wider pool of research — is of course one that has already been made by the many established university presses around us, who (it strikes me) have achieved a level of brand independence (editorial independence? cultural independence?) that enables them to be more selective and/or strategic in what they publish, and therefore more in control of (and more focused on) their own brand. One might anticipate that the new wave of library presses could look to the experience of their older cousins, were it not for the likelihood that the more established university presses typically made their transitions in an era before “brand” would have been up there among the strategic objectives; possibly in an era before the words “strategic” and “objectives” were even used in relation to dissemination of research.

Thus our new library presses effectively face their brand challenges without direct precedent, and I ponder to what extent awareness of this challenge has influenced their high ranking of “brand” as a strategic consideration. Given that Australian libraries are often pioneers, and that library presses are flourishing in so many other countries too, I am curious as to the views of Scholarly Kitchen readers on the strategic importance of brand and the related challenges facing the new crop of library presses. To what extent do they need a brand identity separate to that of the parent institution? If this is necessary at all, is it necessary from the outset or should it be something that materializes over time (the brand platform, of course, being a tool that works best when it is an articulation of existing grassroots strengths rather than an attempt to impose new characteristics from the top down)? And ultimately, is it possible to create a focused brand identity when one core expression of brand, your products, may be so diverse as to defy easy unification, however consistent your visual expression, cultural characteristics, etc?

Discussion

19 Thoughts on "What Does "Brand" Mean for Library-based Presses?"

Charlie, Thank you for an interesting post. In dissecting the “increased visibility and university brand” objective, I think it is worth comparing the approach library publishers are taking to disseminating original work from their institutions to what may have existed before they took charge. Most universities house a “wild west” of publishing operations, many producing what is best characterized as “grey literature.” Things like piles of printed tech reports deserted in a filing cabinet, 1990s conference proceedings thrown up on a server that has now been moved, student journals that rise and fall according to the enthusiasm of the current crop of grad students. Before library publishers dug these out, allocated stable identifiers, and mounted them in branded repository platforms, these publications had no visibility, little obvious connection to their parent institution, and delivered no credit to their authors. Bringing mountains of grey literature out of the closet is clearly not the only thing that library publishers are doing, but it is a quick win and I think a real contribution to improving the visibility of their parent institutions and exerting a certain amount of brand consistency.

My questions are: Do people associate a publisher with a book or periodical? Do people associate a book or a periodical with the owner of the publisher?

There is t he old saw:

A publisher throws a party. At the party the authors talk about the authors of various books, the publishers talk about the publishers and the readers talk about the title!

Harvey, branding is very important in at least two ways: 1) library’s use of approval plans relies heavily on brands that publishers have established for excellence in certain fields (e.g., at Penn State our art history titles were included in a lot of approval plans because of the high reputation we had built in this field over the years); 2) branding is key to authors making decisions about where to publish their monographs since the “prestige” of the publisher’s imprint is taken very seriously by P&T committees.

Sandy:

So branding is important for internal funding and for attracting authors. Yet, university presses are being absorbed into libraries because they cannot sustain themselves on their own ability to support themselves. I wonder why the library? What does a librarian know about publishing?

I just googled three main universities which have presses and asked why should I attend X and not one mentioned their press!

Sandy’s response applies to books, but not to journals. With books, publishers’ brands may be somewhat important — it matters to authors (and, to some degree, to readers) whether a book is published by Harvard UP or by the U of Utah Press. But the same isn’t true for journals. With journals, the brand is the journal title. What matters in most cases to authors and readers is the reputation of the journal, not the reputation of the publisher. A thought experiment illustrates this: if Elsevier were to sell _The Lancet_ to Wiley, would it change faculty demand for access, or change the willingness of authors to contribute? Probably not.

(Another thought experiment, this one for us librarians: try to imagine a faculty member coming to you and saying “The library needs to subscribe to more journals published by [Publisher X].” Such a thing may have happened somewhere at sometime, but I’ve never heard of it.)

Your assumption that presses are being taken over by libraries because the presses are failing is incorrect. In most cases, the reason is to achieve certain synergies (as pointed out by the Ithaka Report of 2007 about university publishing), with presses being able to contribute expertise in acquisitions, copyediting, design, marketing, etc., and libraries being able to contribute IT services, preservation, metadata, platforms, etc.

As for attending a university, whether a university has a press matters not at all to undergraduates because for the most part presses do not serve undergraduates and have no contact with them (except as interns). Grad students, on the other hand, know the reputations of presses in their fields and may be influenced by whether the university they enter as a grad student has a press with a good reputation in that field. The “brand” in that respect also serves as one among a number of factors attracting new faculty, as we at Penn State Press were told on a number of occasions by department heads in fields where we published.

Charles perhaps you can enlighten me as to which university published tech reports and which have “wild west” publishing operations. If you take the word publish to mean issue than yes universities issue reports but they are meant for consumption to whom they are addressed. Companies issue internal reports but I and most would hardly call that publishing. Now libraries may gather all that internal stuff, become the repository for the university, index and create an archive that may one day be useful for historical purposes or for decision making purposes, but I hardly think that is what one would call publishing.

I think what you are doing is calling documents grey literature.

There are centers and departments throughout universities, at least at R1s, that have published working papers and technical reports for many years. Some of these series are very important in the ddiscipline, others have a narrower, perhaps local, audience. What separates these from monographs or journal articles is the lack of external peer review, but otherwise usually report on some form of research. When the web came along, these were distributed there on, sometimes funky, web sites rather than sent out in print. Organizing these under a library publishing service relieves the centers and departments from having to maintain web sites for them and often give a consistent look and feel. To some degree it’s still the wild west but the fences are going up.

If I’m not mistaken, the University of California Press provided just such a service for a while to departments in the UC system. I’m not sure the press is still doing this, but Alison Mudditt can tell us.

Hi Harvey, The Joint Transportation Research Program (JTRP) at Purdue University is a good example (http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/jtrp/). Each report (about 30 a year) is subjected to a form of peer-review, then copyedited and formatted by the Library, before being issued with a DOI and published through the IR. The 1500+ reports online get ca. 250,000 downloads a year. There are quite a few more series like this, especially at public universities with a heavy engineering and technology focus.

When our library and press at Penn State jointly established the Office of Digital Scholarly Publishing in 2005, we had to confront the challenge of distinguishing between publications that had been vetted through the usual peer-review process and those that had not. Here the advantage of having a separate university press as a partner made all the difference in the world. We published an OA monograph series in Romance Studies through the ODSP and handled it in the same way we would have handled any print series, including the books in our seasonal catalogues, taking POD copies to exhibits, etc. In that way people could understand that books in this series should carry the same weight as any of the press’s other publications. Other publications of the ODSP, like conference proceedings, were not included in press catalogues and thus “branded,” but instead promoted in other ways. We did publish one series that reprinted public-domain books about Pennsylvania and included these books in our catalogues, but these were obviously very old titles that did not pretend to be new contributions to scholarship. The challenge for libraries that do publishing and have no established university press to partner with is obviously greater with respect to properly “branding” publications that are meant to be seen as peer-reviewed advances in scholarship. At least one library, at Amherst, solved this problem by creating a new university press.

Charlie, you ask, To what extent do they need a brand identity separate to that of the parent institution? If the parent institution enjoys a stellar reputation, like Harvard, Oxford, etc., the press brand gets a boost.

If the university doesn’t rank high, then the brand could be developed as a separate identity.

You ask: If this is necessary at all, is it necessary from the outset or should it be something that materializes over time (the brand platform, of course, being a tool that works best when it is an articulation of existing grassroots strengths rather than an attempt to impose new characteristics from the top down)?

My understanding of brands from Martin Kornberger’s bible, ‘Brand Society’ says that brands function in a subversive, almost anti-corporate capacity, that exposes the innards of an organization more fully to the outside. Ergo brands really aren’t top down, or wouldn’t function in a top down capacity.

Brands become a consumer feature that speaks to lifestyle, status, and identity. so a university press that wants to brand its self as a separate identity from the parent has to get some lifestyle, status and identity features. These features come from interaction with brand consumers: authors, readers, book buyers, suppliers, librarians, other presses and so on.

A university press would need to develop some features in conjunction with these consumer groups to make a composite consumer identity. Encouraging consumers to talk about the product and featuring the product in lifestyle settings develops the brand. Brands evolve with consumer input and but brand values don’t change.

You ask. And ultimately, is it possible to create a focused brand identity when one core expression of brand, your products, may be so diverse as to defy easy unification, however consistent your visual expression, cultural characteristics, etc?

All the publications of a press could be branded with a logo which represents the values of the products: think Intel..

Why not use the word reputation?

I thought branding died with the failure of GM

Hi Harvey – I think reputation could certainly be synonymous with “brand image” i.e. the bit you can’t control – how well people know you and what they think of you. But I’m not sure the word reputation works for the other aspects of brand, at the end of the spectrum where you do have some control (what products and services you offer, how you present them, the behaviors you encourage in your organization).

Thanks, Sherio. I fully agree that a brand can’t function top-down, and to really build a brand successfully you need to grow from grassroots characteristics. On the last point, I’m thinking beyond the application of a common visual identity and wondering about the importance of product consistency to brand. Some of the comments above give useful examples here – can such a range of content, from grey literature to peer reviewed monographs or journals, ultimately cleave together and form the basis of a recognisable brand? Sandy touches on a couple of useful points in that respect (and indeed Roxanne at ANU had also mentioned the first one) – using “series” branding, effectively, to differentiate between different types of content – and thereby a press can be known for something (e.g. art history monographs) while also, relatively separately, publishing other content. And I suppose that’s true anywhere – no brand identity / values are 100% pervasive and you can be primarily known for one thing while also quietly doing other things.