In business, it is often said that attracting a new customer is far more expensive than keeping a current customer. This is why companies create so many incentives and rewards for their current customer base. In exchange for our loyalty, we often sign up to membership programs that give us discounts, priority, and tangible rewards. Consider for a minute how many membership cards you possess.

In the early 2000s, BioMed Central created the first institutional membership model to provide authors with free or discounted access to publish in their portfolio of open access BMC-branded journals. Other open access publishers, including PLOS, quickly followed suit. What BMC understood early on was that while authors are very sensitive to the price of publishing, institutions are less so. This is why most publishers are — or quickly become — institution-facing.

More than a decade later, in 2012, PeerJ‘s individual lifetime membership model, where one could “pay once, publish for life” took the industry by surprise, not because their initial price (starting at $99) threatened to severely undercut its competitors, but because their business model was author facing. It also wasn’t clear how PeerJ was going to bring in additional revenue once an author purchased a lifetime membership.

Unlike other loyalty business models, PeerJ‘s lifetime membership model costs the company money each time a satisfied customer decides to submit another manuscript. Provide better author services and they’ll keep coming back. On the face of it, their business model looks oddly self-defeating.

The success strategy of the “pay once, publish for life” business model is to attract new members, and the simplest way to do this is through co-authors. Researchers love to collaborate and the research environment is prone to change as graduate students, post-docs, and professors move into, and out of, institutions. Under the lifetime publishing model, a loyal customer is someone who returns with new friends.

Did PeerJ discover a winning business strategy based on the lifetime membership model?

To answer this question, it is not enough to look at PeerJ article output, since it tells you nothing about whether (or how much) an author paid to publish. One must look at the rate of new and returning authors. For the lifetime membership model, success means that the rate of new authors (which represent new revenue) is greatly outstripping return authors (which represent growing costs).

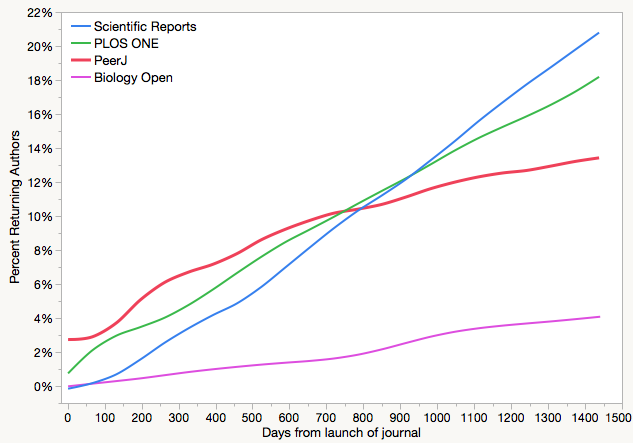

To see whether new authors were outstripping return authors, I analyzed PeerJ author lists over the first 4 years of publication (Feb 2012–Feb 2016, n=2948 papers). To provide some perspective, I did the same for three other biomedical open access journals that use the APC (pay for each paper) model: PLOS ONE (Dec 2006–Dec 2010, n=14773), Scientific Reports (Jun 2011–Jun 2015, n=10834), and Biology Open (Jan 2012–Jan 2016, n=622). I should note that Biology Open is far smaller and not does operate under the distributed editorial model of the other three journals.

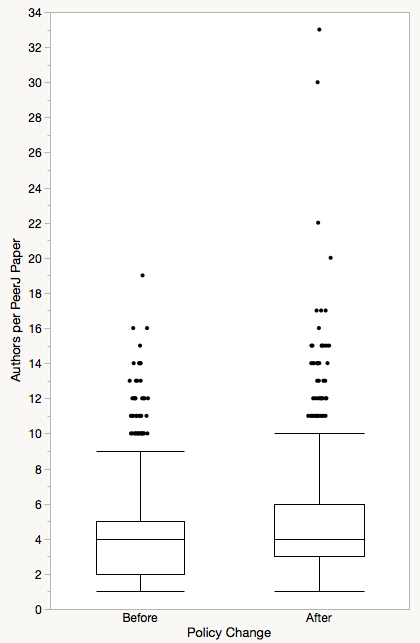

The first thing that was apparently clear was that PeerJ papers listed significantly fewer authors: PeerJ (median 4 authors/paper, IRQ: 3–6), PLOS ONE (6, 4–9), Scientific Reports (6, 4–9), Biology Open (5, 3–7). Considering their business models, these results should not be surprising. Under a membership model, coauthors may be less willing to be listed on a paper if they were required to purchase a membership; submitting authors may be less generous with providing colleagues with honorary authorships; or the administrative burden of purchasing individual memberships may be perceived unfavorably. PeerJ‘s business model may disproportionately attracted researchers who work in smaller teams (ecology, computational biology, paleontology) over larger teams (clinical trials, public health epidemiology, high-energy physics). Whatever the reason(s), PeerJ author lists were significantly shorter than the other journals.

The second difference was that for the first two years after its launch, PeerJ had higher rates of returning authors. This changed around day 730, when it was surpassed by Scientific Reports and PLOS ONE.

I must admit that author disambiguation is pretty difficult without unique identifiers. While many journals are now implementing policies to require ORCID registration, I’m simply working with text names. And for very large journals (like PLOS ONE and Scientific Reports), the probability of mislabeling an individual as a returning author is higher than for smaller journals like PeerJ and Biology Open. Still, PeerJ‘s growth resembles a curve while the other journals resemble straight lines.

What is taking place at PeerJ that may help to explain its distinctive growth curve? On Feb 11, 2014 (day 360) PeerJ announced that 20 institutions had set up accounts that would purchase memberships for their authors. This follows an earlier announcement that all Max Planck authors could publish in PeerJ for free. PeerJ received its first Impact Factor in June 2015 (around day 850), which resulted in an influx of new authors, according to Peter Binfield, founder and publisher of PeerJ, and former publisher of PLOS ONE. Then, on Oct 19, 2015 (day 968), PeerJ announced that authors could pay the traditional APC fee to publish their article in lieu of author memberships.

Peter Binfield declined to share membership numbers with me; however, the series of company announcements speaks for itself: PeerJ was becoming institution-facing.

Using PeerJ‘s APC policy announcement to split the dataset into two largely-equal bins, you can see how the distribution of PeerJ authors has shifted up (Figure 2). There was no shift in the author distribution of the control journals over this time.

What made PeerJ so unique in 2012 was its author-facing membership model that strove to build author loyalty while promoting itself as an alternative to more expensive alternatives.

“The costs of research publishing can be much lower than people think,” stated Peter Binfield in a 2013 Nature article on the costs of open access publishing.

Today, there is no lack of low cost open access publishers, promising fast publication at rock-bottom prices.

Since 2012, PeerJ membership prices have increased with Basic Memberships now starting at $399 (up from $99). PeerJ‘s APC increased from $695 in 2015 to $1,095, a price that is quickly approaching the industry standard.

And while more papers are being published in PeerJ each year (1298 in 2016, up 62% from 2015), this volume represents just 6% of PLOS ONE‘s 2016 output. Last year, PeerJ launched a second journal, PeerJ Computer Science. To date, it has published 111 papers. While overall publication output seems too low to return a profit, Peter Binfield assured me that his company is now self-sustaining.

Still, this leaves PeerJ (the company) in a challenging financial position. When competing on price, a publisher must relentlessly push for high volume. Some megajournals have given up on copy-editing, generating page proofs, and automate as much of the publication process as possible in a relentless obsession to speed production and trim costs. Delivering great customer service is antithetical to bulk publishing.

PeerJ‘s next Impact Factor anticipated to stay around 2. Meanwhile, PLOS ONE is anticipated to drop below 3, which may make PeerJ more competitive for authors sensitive to IF scores. However, both journals are still competing against Scientific Reports, which has recently become the largest multidisciplinary megajournal.

PeerJ does appear to have a small group of loyal authors. For example, Danilo Garcia has co-authored 16 papers since 2013. Antonio Palazón-Bru and Robert Toonen have co-authored 12 papers and 10 papers each. Both also serve as PeerJ Academic Editors. Loyalty to one megajournal is not unique to PeerJ, however. The difference is that Garcia Palazón-Bru, and Toonen are all PeerJ members and therefore do not pay for each new paper published in PeerJ. Their value to the journal is only realized when they bring in paying co-authors.

In conclusion, PeerJ entered the market in 2012 with an innovative author-facing, low-cost membership publication model. It appears that the company has pivoted toward the industry standard APC model charging industry standard rates. And by pivoting to the APC model, PeerJ turns away from its one unique feature to face a crowded megajournal market where automation and scale (or subvention from a parent company) may be the only way to survive.

Discussion

4 Thoughts on "PeerJ Membership Model and The Paradox Of The Loyal Customer"

I’m the co-founder with Peter Fernandez, of the U. Tennessee Institutional Arrangement with PeerJ http://www.lib.utk.edu/agvet/peerj/. Other librarians in our management and collections and liaison teams were also involved in reviewing and establishing the Arrangement with PeerJ. The PeerJ Institutional Arrangement is easy to administer. The team at PeerJ has been unfailingly professional and supportive. PeerJ had case reports that we used in explaining the PeerJ business model to our library colleagues. We used the Oregon State Case Study (https://peerj.com/institutions/case-studies/19/oregon-state-university/). We can top up with any amount at any time. Here is an example of how we’ve used the funds in the PeerJ Institutional Plan: Two University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine students published the results from summer research immersion experiences, work they did during summer 2016. We are so proud of them! (https://peerj.com/articles/3101/, https://peerj.com/preprints/2398/ ). On both articles the students included biostatisticians that consult at the Pendergrass Library as co-authors.

On the changes to APC: PeerJ is attempting to innovate, but not leave the community behind. PeerJ still offers the lifetime publishing plans. As I understand it, changes to Institutional Arrangements were made based on feedback from institutions with arrangements, which is how PeerJ does everything—in consultation with the community. “However, for Universities, we have found that the APC option makes most sense for their accounting, and is easiest to understand when explaining to their administration and faculty. Therefore institutions can pay the PeerJ ‘APC’ fees (but not the Membership fees) in one of two ways:” (source https://peerj.com/blog/post/85002106083/how-an-institutional-arrangement-works-at-peerj/)

PeerJ is affordable, high integrity, and one of the first in biomedical publishing to offer a preprint server. Besides PeerJ, what other journals format the references for authors? Post by Davis above focused on how that kind of attention to quality is being left out of other journals. See @thePeerJ or the PeerJ blog (https://peerj.com/blog) for more innovations including:

• PeerJ has a reviewer match, https://peerj.com/reviewer-match/

• PeerJ sends authors a feedback survey to support their goal to have publishing be a pleasant experience. More about the PeerJ philosophy here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dkOxE7N-5b8.

• How about the graphical abstract option available to PeerJ authors? — see example here https://peerj.com/articles/715/#annotation-1239.

• How about the way PeerJ handled getting an IF? (https://peerj.com/benefits/indexing-and-impact-factor/#impact-factor): “Whilst we appreciate the importance still placed on the Impact Factor by many elements of the academic community, we do believe that individual research articles are best assessed on their own merits, rather than on an aggregate citation count for the journal in which the work is published. This is also why we periodically publish PeerJ’s citation distribution. ”

• One more thing; authors get a post publication checklist to prompt them on getting the word out about their work. PeerJ is author-centric, and so are librarians.

• PeerJ also has optional open peer review, so it helps the faculty teach about peer review.

I’ve tried to list just some of the innovations on offer from PeerJ that were left out of the SK/Davis blog post above. I encourage other librarians with PeerJ institutional plans to comment.

Hi Ann,

I suspect the author didn’t get too deep into the many features of PeerJ’s offerings because the blog post wasn’t really meant to be a marketing piece for their journals, rather an analysis of their unique and innovative business model and how it has fared in recent years.

One other thing not mentioned is their for-profit status and ownership by venture capitalist investors. In an era of increasing hostility toward commercial ownership of the scholarly communications market, it’s interesting that this doesn’t seem to have had much effect on the perception of PeerJ or its uptake by universities/libararians.

Ann, I’m glad that you have a wonderful relationship with PeerJ; however, my post was not about PeerJ innovations, professional customer service, or how librarians are using their collection funds to support their authors. This post was about PeerJ’s business strategy and how it has changed from a lifetime membership model to a institutional support model. If you could keep further comments focused on the latter, I’d be happy to discuss. Thanks for your understanding.

Davis: see second paragraph.