While there is a steady stream of journal articles criticizing peer review, a recent publication, “Comparing published scientific journal articles to their pre-print versions”, has a number of major problems. It’s perhaps ironic that a paper finding no value in peer review is so flawed that its conclusions are untenable, yet its publication in a journal is itself an indictment of peer review.

The article’s premise: journal peer review is meant to improve manuscripts, thereby justifying the cost of APCs and subscriptions. The authors hypothesize that those improvements should lead to measurable changes in the article text. They obtained preprints from arXiv and bioRxiv and located their published equivalents, then used a suite of text divergence metrics to compare them.

There are three serious problems right away:

- That ‘more rigorous peer review = more text changes’ sounds plausible, but the authors don’t test this. It’s easy to imagine lots of exceptions (e.g. a very good paper). So, no matter what level of text differences they find, the authors can’t link those differences to the ‘value’ of journal peer review. This oversight fatally undermines their “journal peer review does nothing” conclusion.

- The authors assume that a posted preprint has never been through peer review. A significant fraction of preprints (particularly the later versions) may well have been reviewed and rejected by a journal, and then revised before being reposted to arXiv. Comparing these preprints with the published versions will greatly underestimate the effects of peer review on the text.

- Rejected articles often do not end up in print, so the authors cannot examine the other key value proposition of peer review, which is identifying and rejecting flawed articles. Moreover, being restricted to accepted articles biases the dataset towards articles that required fewer revisions during peer review.

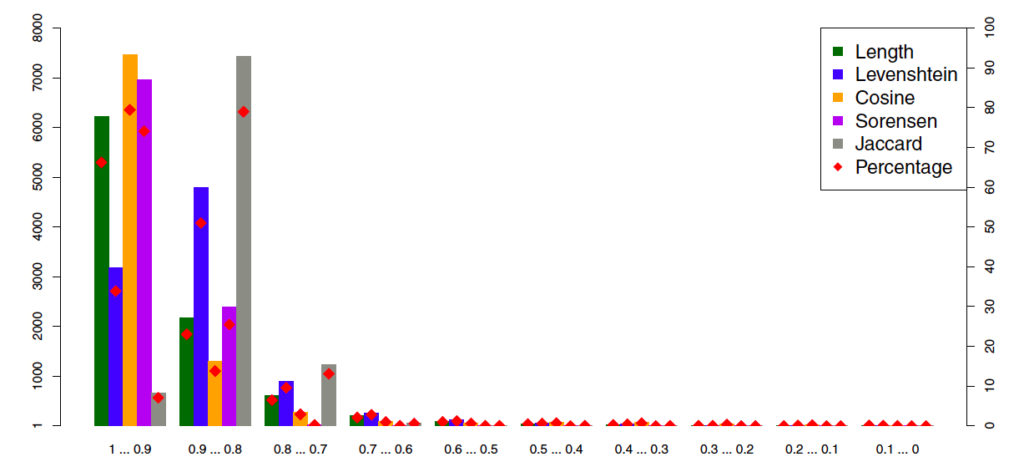

Their main analysis focuses on the arXiv corpus of articles, and here we also encounter a major problem with the paper. The authors find that the body text of preprints and published articles are (by their metrics) almost identical. Their Figure 5 is below, with the bars showing the number of articles within each metric value bin. (For example, just over 6000 articles had a length comparison score between 0.9 and 1.)

The authors conclude:

The dominance of bars on the left-hand side of Fig. 5 provides yet more evidence that pre-print articles of our corpus and their final published version do not exhibit many features that could distinguish them from each other, neither on the editorial nor on the semantic level. 95% of all analyzed body sections have a similarity score of 0.7 or higher in any of the applied similarity measures.

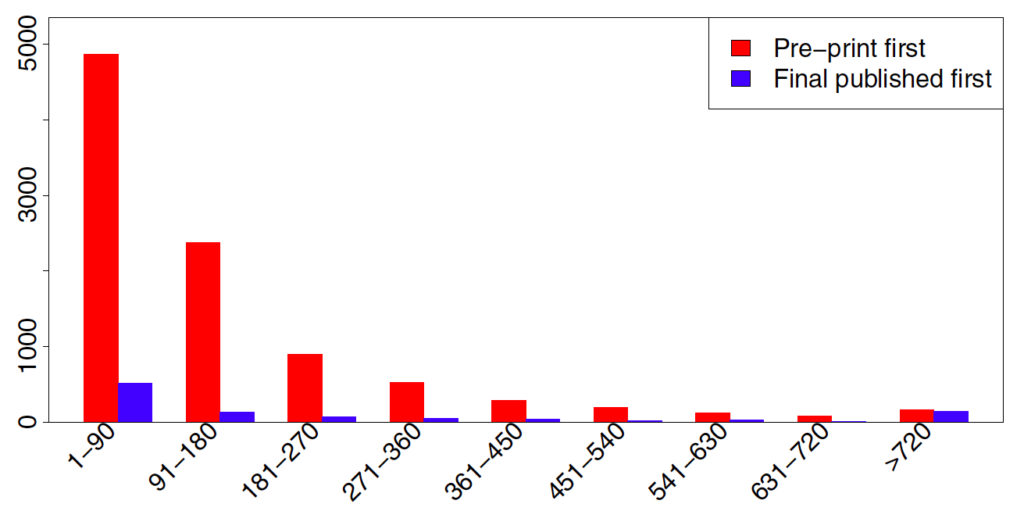

However, these data are based on a comparison of the last version posted to arXiv with the published article. It’s well known that authors often update their arXiv entries with the version that the journal reviewed and accepted for publication. Figure 6 suggests that this is precisely what is happening: most of the final versions were posted to arXiv less than 90 days before the article was published, and some even are posted after publication.

As a Scholarly Kitchen reader, you’ll be (painfully) aware that it’s rare to get an article submitted to a journal, peer reviewed, revised, resubmitted, re-reviewed, accepted, typeset, and published in under 90 days, or even 180.

Most of these final arXiv versions have therefore already been through peer review, and any observed text differences between them and the published article are due to trivial changes during copyediting and typesetting. The authors’ main analysis thus tells us nothing about the value of journal peer review.

Next, the authors move to the dataset they should be analyzing: the body text of the first version posted to arXiv compared to the published article. They still don’t take any steps to remove articles that have already been through peer review, by, for example, excluding those that were posted less than 180 days before the published article came out, or those that thank reviewers.

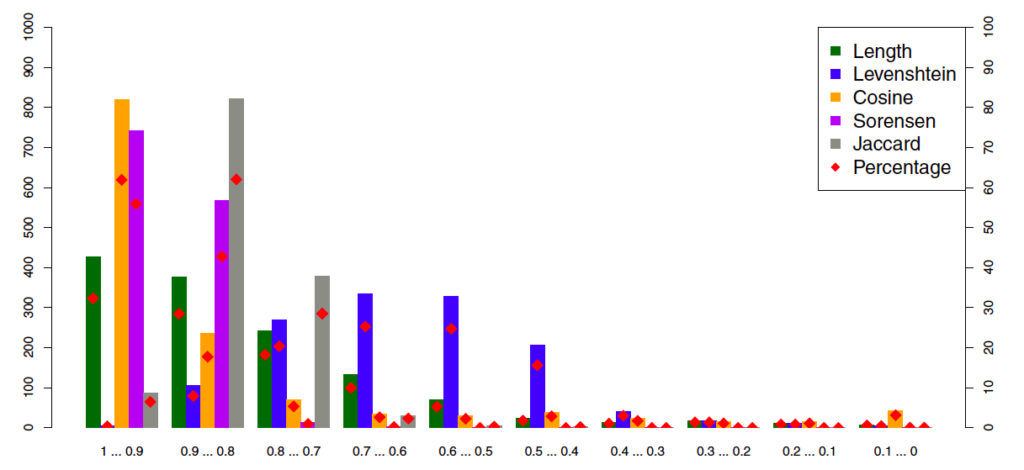

Although the figures are in this part are very hard to understand (Figure 9 shows the % difference between Figure 5 and the equivalent, unavailable, bar chart for the first arXiv version), it seems there were more text differences between preprints and published articles in this comparison. Nonetheless, as noted above, we have no benchmark for the level of text difference expected for an article that has had a thorough peer review process versus one that has not, so it’s still impossible make any connection between the text changes seen here and the value of the peer review process.

Lastly, the authors repeat their analyses for articles from bioRxiv. Since bioRxiv prevents authors from uploading accepted versions, differences between the preprint version and the published version should more reliably represent the effects of peer review (even though they are still analyzing the last preprint version). The authors do not attempt to identify preprints that have already been through peer review, either at the publishing journal or another that reviewed the article and then rejected it. As noted above, this biases the study towards finding a weaker effect of peer review.

The equivalent of Figure 5 (above) for bioRxiv looks like this:

Here, there have clearly been substantial changes to the body text between the preprint and the published stage. The authors explain their different results for arXiv and bioRxiv as follows:

“We attribute these differences primarily to divergent disciplinary practices between physics and biology (and their related fields) with respect to the degrees of formatting applied to pre-print and published articles.”

This explanation seems like an attempt to get the data to fit a preconceived conclusion (I would be interested in hearing thoughts from any physics journal editors reading this). A more plausible reason is that the bioRxiv dataset really does (mostly) compare articles from before and after peer review, and that peer review has driven substantial changes in the text. The authors seem curiously reluctant to embrace this explanation.

Does it matter that an article in an obscure journal suffers from both flawed methodology and a presentation heavily in favor of the authors’ preferred result? Yes – it matters because articles in peer-reviewed journals have credibility beyond blog posts and Twitter feeds, and this article will doubtless be held up by some as yet another reason why we don’t need journals and peer review.

We do need more research into peer review: we have to understand when it works and when it doesn’t, and how the motivations of the various parties interact to drive rigorous assessment. The PEERE program is doing exactly this.

However, useful assessment of peer review requires high quality, objective research. The authors here are doubly guilty: their article is so poorly conceived and executed that it adds nothing to the discussion, yet the authors are so keen on a particular outcome that they are willing to retain flawed datasets (the final version arXiv dataset) and brush contrary results (the bioRxiv dataset) under the carpet.

Some of these issues were brought to the authors’ attention when they posted this work as a preprint in 2016. Unfortunately, they chose to submit the article to a journal without addressing them. Somehow, the journal accepted it for publication, warts and all. This tells us three things:

- The preprint commentary process is not sufficient to replace formal peer review. With no editorial oversight, and nothing to be gained by authors for correcting errors that invalidate their conclusions, authors are under no obligation to fix their article.

- Formal peer review remains a flawed process. The journal’s editor and reviewers could (and should) have forced substantial revision – because they didn’t, yet another weak article about peer review has joined the public record.

- This piece itself should count as post-publication peer review. Regardless of whether I’ve convinced you of the paper’s flaws, their article will still be sitting, unchanged, on the journal’s website.

Given the many flaws identified, particularly the lack of a clear link between text changes and peer review quality, this article is mostly of interest to people who like text analysis. We can only hope that the community is able to resist using it as evidence that we ought to abolish journals.

Discussion

23 Thoughts on "Peer Review Fails to Prevent Publication of Paper with Unsupported Claims About Peer Review"

Tim, thank you for a critical review of a paper that is receiving undue praise. There is another fundamental shortcoming with how the authors attempted to measure the value of peer review. They merely count bulk changes to text and completely ignore what makes a substantial change. For example, consider the following textual change:

The results prove that peer review adds no substantive value to journals.

to

The results suggest that peer review adds little substantive value to journals

While I just changed 2 out of 12 works, the change is pretty substantial. Imagine if a dosage of 0.1 was changed to 0.01. The difference could mean life and death to a patient. Measuring similarity scores across an entire text is not enough: One must look at the type of changes. Adding a reference to a paper or a perfunctory statement is not as important as changing the results or interpretation of a study.

I’ve seen many times where the addition of the word “no” has been an outcome of peer review (“effect” to “no effect” or “benefit” to “no benefit”), changing the meaning of the paper entirely, and leading some authors to remove a paper from peer review because their claims were seen to be overstated or wrong.

You have a typo — “works” should be “words.” Just a small wording change. Would that count as peer review having an effect?

Exactly the questin I asked on Twitter yesterday. Quantity of changes is one thing … quality of changes is another. Would love to see that investigated somehow.

Irony is dead.

Long live ironing.

🙂

Unfortunately recent data regarding the echo-chamber effect of social media indicates that this article will be used as evidence even though it’s highly flawed. It is even more unfortunate that this blog post will raise the profile of the article within our flawed system of publication metrics that values quantity over content.

Related to the above chain is the question of how to assess reviews themselves, especially since (to my understanding) Publons is considering adding a “score” element to their upcoming Reviewer Connect feature. On the other side of what Phil mentions, one review could be 500 words longer than another but be generally focused on grammatical and formatting issues, rather than engaging with the content. But how do we score things like “quality” when we also have to consider that reviewers might be invited because they represent different sub-sections of a discipline, and those distinct views are of differing value to the editor? And how heavily weighted are those factors against timeliness of a completed review, which factors into time-to-acceptance and time-to-publication?

Not to mention things like statistical or replication checks, which for accepted papers may be more likely to be confirmations than checks requiring substantive text changes.

Can you think of a new metric that has (in the long run) actually improved peer review and academic publishing? In this case, the only way to get a decent measure of the review’s ‘quality’ would be to ask the editor to give it a score out of 10.

I don’t mean to be flippant, and I don’t know if it could be called a “new” metric, but the relative consistency of JIF for individual journals over several years is an implicit comment on the value of peer review. JIF validates journals (not individual articles), and a consistent JIF validates the editorial program of the journal (or invalidates it with a low JIF). For the record, I think the value of all these metrics is vastly overstated and the ongoing discussion (and investment in them) a waste of time and money.

Joe, I wholeheartedly agree.

This article is starting to stir up a lot of excitement, especially in the academic library world. When I pulled up this article showing the altmetric score (as of 10:37 am edt), it was 192 with indicators as to where comments are coming from. It is mostly twitter, with 264 tweets by 240 tweeters, plus discussions from four blogs and two google searches. Interestingly, Altmetric pulls Tim’s blog entry here and puts it at the top (reverse chron. order), but if I google the article title (because it’s embedded here), it doesn’t pop up for me. If you browse through the tweets, there are some fairly high-level people in the academic word who are taking this article at face value.

This is why it’s so crucial that editors and reviewers do their jobs properly and force extensive changes on bad papers like this one. There’s nothing that can really be done once it’s been published to make sure that people don’t take action on what are (in this case) deeply flawed conclusions. It’s even more problematic when those deeply flawed conclusions reinforce peoples’ preconceptions, so that they don’t trouble to question the veracity of the paper.

You could reach out to the editor, and encourage the journal to issue an Expression of Concern, or to talk to the authors about a possible retraction. The contact information for the Editorial Board is readily available on the journal website: http://www.springer.com/computer/database+management+%26+information+retrieval/journal/799?detailsPage=editorialBoard

Blog posts like this are an important way to educate the community, but as N. Lee suggests, they could get lost in the noise. Sometimes the direct approach is called for.

The authors are not particularly interested in improving or retracting their paper: I raised most of the above with them when they posted their preprint, and they made no attempt to fix the issues (including the major flaws with the last arXiv preprint dataset that they lead with). The article as-is supports their agenda and that’s all that matters.

The journal has a responsibility to the content regardless of what the author’s want. As a publisher, I’ve had to act on papers even though the authors didn’t want to retract or issue an errata, because it was a real problem that could not go undocumented in the literature. Of course not every accusation can be acted upon, but if you don’t draw attention to the problem, it can’t be fixed.

Remember Hanlon’s razor: “Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.” Sometimes bad papers sneak through. Now, if you’ve already alerted the editors to your concerns, and they also chose to turn a blind eye, that’s a different story. But that’s not what your comments suggest.

Yes. I believe it was Mark Twain who said: “A lie can travel half way around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes.”

The original title of the paper, when it was first presented at CNI, was “What does $1.7billion get you?” (https://www.cni.org/topics/assessment/how-much-does-1-7-billion-buy-you-a-comparison-of-published-scientific-journal-articles-to-their-pre-print-version) – a reference to the library community’s collective spend on subscriptions to journals. Framed in that way—As a library faced with the choice to subscribe to a journal or rely on the freely available preprints, is the difference worth the cost?—I think the paper is a slam dunk. If Vines is right and the differences are minor because the freely accessible version in many cases actually reflects the value added by peer review, that only makes the argument stronger—the free version actually includes whatever genuine value is added by the for-profit publishing process, and all you get for your $1.7 billion is some minor copyediting. If Vines is right, there is (perversely, given the equally unpromising trajectory of the current model) a sustainability problem with switching to reliance on preprint servers: if everyone canceled their subscriptions and turned to ArXive and its growing body of analogs, the publishers would fold up and the peer review process would have to be managed another way. But that’s a problem I think libraries might rather have than the current model of being presented every few years with constantly-growing million-dollar offers they can’t refuse.

Also, I notice that David Crotty’s recent post about preprints (https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2018/03/14/preprints-citations-non-peer-reviewed-material-included-article-references/) relies on the assumption that preprints have NOT benefited from peer review. The excerpt on the front page reads, “Preprints are early drafts of a paper before it has gone through peer review. Should non-peer reviewed material be included in published article reference lists? If so, how can we make that clear to readers?” Indeed, the whole notion of a “version of record” casts doubt on preprint versions as lesser, and perhaps dangerously so.

So, are preprints dangerous rough drafts, or are they basically the final articles with all the value added by the peer review process? Who’s right, Tim or David?

As Tim notes, there is no way of knowing whether any given preprint has received any sort of peer review (aside from publicly posted comments, which only about 10% of what’s on biorxiv receive, and even then, there’s a big difference between a “comment” and a “peer review” https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2012/03/26/the-problems-with-calling-comments-post-publication-peer-review/ ). So given the uncertainty, the reader should treat any preprint as un-reviewed. Note also that the journal I was discussing was a biomedical journal, and as this flawed study showed, there are more differences between what’s on biorxiv and in a journal (the authors try to handwave this away). And to be clear, I am strongly in favor of the use of preprints and their citation in papers, provided some level of transparency about what is being cited (this includes websites, datasets, code and other things that may or may not be peer reviewed).

So should it reach the point you suggest (libraries drop physics journals and just use arxiv), then you would probably see journals tightening their reuse policies to prevent posting the accepted manuscript version on arxiv until an embargo had passed (or requiring payment of an APC). Realistically, moving to a gold OA model is more likely than the publishers going out of business and a brand new way of ensuring peer review arising.

But the most important point is that the study in question here fails to understand much of the value of peer review. It ignores the value in having the literature culled of unsupportable works, it ignores the validation, designation and filtration functions of peer review and publication (https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2010/01/04/why-hasnt-scientific-publishing-been-disrupted-already/). There’s more happening here than simple changes to text.

Hi Brandon – thanks for your comment. David’s line about preprints and my own can be squared by changing his a little bit: “Preprints are early drafts of a paper before it has been published by a journal.” There’s thousands of preprints out there, and some have been through peer review (especially their later versions) and some haven’t. It’s often very hard to tell how much peer review a preprint has gone through, so unless readers can easily access that review history and see the level of rigour themselves (by reading the reviewer comments and the authors’ response), it’s risky to assume anything about a preprint.

Thanks, Tim! Perhaps, then, the finding of the article under discussion could be recast as, “Most preprints on ArXiv appear to include all or substantially all of whatever changes were made as a result of the peer review process.” With that finding in hand, the risk of citing to a version that lacks a significant improvement from review is substantially reduced for at least that category of preprints, though of course any particular preprint might not fit the trend.

I wanted to comment on your last piece, https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2018/03/07/curious-blindness-among-peer-review-initiatives/ but I was away for several weeks and missed my chance. Like Tim Gowers and others I run an OA journal – as an academic with no budget, staff, hardware (just a laptop), using OJS and hosted at a big US university library. This is entirely possible, and academic interest in editing has not dimmed over the years. While some editorial help would have been welcomed, we manage without it. Our system of peer review would certainly have caught the deficiencies in the article mentioned in this post. Some of our published papers began as preprints, but few (preprints not too popular in the social sciences we draw on). The editorial process we use tends to weed out plenty of factual, grammatical, and referencing errors because we have time for dialogue and we have no budget constraints. And any suspicious work just doesn’t get published. As Tim Gowers notes, we can amend a mistake in an article and repost it given our OA format – a small error is never permanently on record. This is one benefit of having no commercial interests – we are more interested in the knowledge produced and its accuracy than eating into profit margins, which can lead to putting out questionable articles [although not in the top journals ] or having to devote staff time to amending a published article or issuing an errata. But this whole issue of styles of journal publishing touches on questions of social justice, about which I write here https://fennia.journal.fi/article/view/66910

“The more revisions a paper undergoes, the greater its subsequent recognition in terms of citations” http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2018/04/10/the-more-revisions-a-paper-undergoes-the-greater-its-subsequent-recognition-in-terms-of-citations/