Innovation in peer review is a hot topic, with major efforts focused on streamlining or changing a publication’s version of the traditional process so that reviews are more transparent (signed or published) or speedier or less difficult to transfer for authors whose manuscripts are rejected.

An interesting experiment has been going on for a half-decade, yet isn’t front and center in conversations about peer review innovation. This is the BMJ’s approach to inviting patients and caregivers (called “carers” here) dealing with particular health conditions to review relevant manuscripts. The paradigm shift this represents strikes me as significant — searching for an image for this post showed that nearly all the doctor-patient relationships portray physicians talking (often, literally talking down) to patients, as the experts. But patients with health conditions and their caregivers often become experts in their own right, visiting specialists, hearing differing opinions, learning the ins and outs of coping with chronic or acute conditions, and holding their own insights into what it’s like to actually experience a cancer, a heart condition, diabetes, mental illness, or surgery.

I was at a meeting recently when I recalled this initiative out of the blue, and I grew curious about whether it still existed, how it had done, and so forth. I contacted BMJ, and they were kind enough to respond to a dozen interview questions. The respondents contributing to these answers are:

- Tessa Richards, Senior Editor/Patient Partnership, BMJ

- Amy Price, Patient Editor (Research and Evaluation) BMJ

- Sara Schroter, Senior Researcher, BMJ

British spelling variants in their responses have been preserved. We colonist-taught copyeditors still notice these . . .

As you’ll see, the initiative is going strong, has led to many changes in how manuscripts are reviewed, is well-received by all involved, and has been expanded in interesting ways. That sounds like a success by any measure. Enjoy this story of a successful innovation in peer review.

A few years ago, BMJ implemented a way for patients to review manuscripts. When and how did this start? What was the motivation?

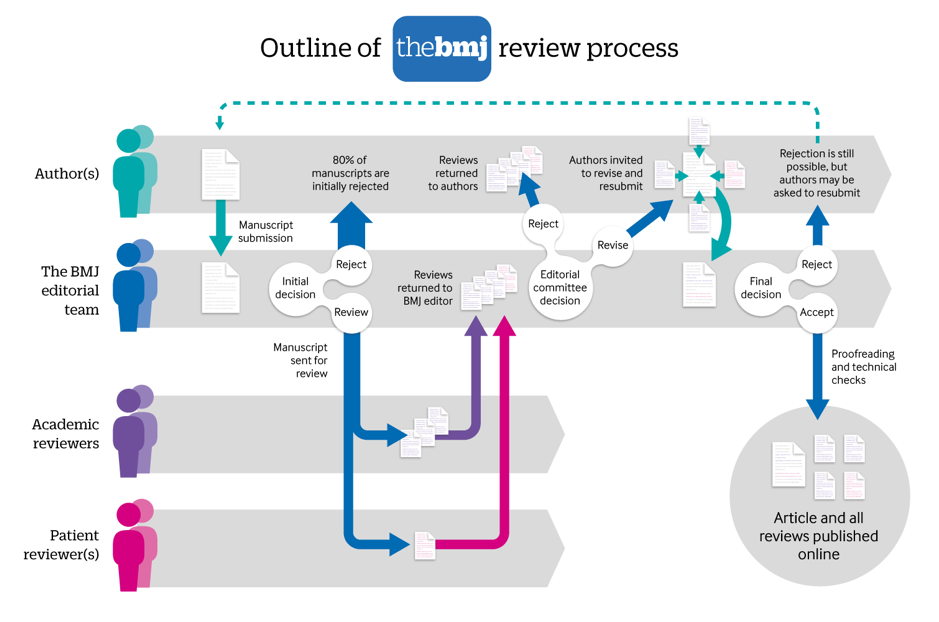

In 2013 The BMJ committed to setting up an international panel of patients and patient advocates, to co-produce a new patient partnership strategy to advance the “patient revolution” in healthcare. The journal has been actively advocating for patient partnership for over 25 years, but we agreed that a co-produced strategy which saw us “walking the talk” on patient partnership in our own editorial process would make our advocacy for it both more credible and effective. Our aim being to spur on international efforts to improve the quality, safety, value, and sustainability of health systems through realising the transformative potential of working in partnership with patients, their families, local communities, and advocacy groups. Our strategy embraces a range of measures to co-produce content with patients and the first step we took, in January 2014, was to initiate patient review of research papers alongside peer review. This was shortly followed by a request to all authors of research papers to document if and how they involved patients in their study. This is now a mandatory requirement, and entails authors providing answers to set questions including if and how patients were involved in defining the research question and outcome measures, the design and implementation of the study, and the dissemination of its results.

What have the results been thus far in general? How many papers have experienced this kind of review? What percentage?

Setting up patient review of papers was initially challenging as it was a novel innovation, but the process is now well-embedded, and editors have embraced it. We have around 700 patients and carers registered for patient review. So far, we have sent out close to 2,000 invitations to patients and carers, and have received 754 completed reviews back. This level of acceptance and return of reviews is very similar to that of peer reviewers. Between January and March 2018, 26% of papers sent out for external peer review also had a completed patient review. Over the last two years, we have extended patient review beyond research papers and now routinely send educational articles and some comment articles to patients as well as peer reviewers.

Last year we surveyed patient reviewers who had reviewed recently, and had an excellent response rate (n=122/164, 74%) showing a high level of engagement with the initiative. Feedback was positive and constructive. Patient reviewers shared many useful insights and ideas on how to improve patient review of BMJ papers, and we are currently discussing how to implement them.

Here are some illustrative quotes from patient reviewers:

“I have already suggested to a number of other advocates they should apply to become a reviewer. I find the process very inclusive and it is one of the few places where I feel we are invited for the right reasons. We aren’t tokens in the BMJ process, we are equal and valued voices.”

“I am cautious about who I share information with in terms of my health. Just putting my name out there as a patient reviewer exposes some of that. I have decided that the benefits of being a BMJ peer reviewer are greater to me than the risk of exposing myself that way, but it was a consideration.”

“Initially I was worried that my lack of in-depth knowledge of statistical methods would make my comments seem petty or too simplistic. Yet when I read expert reviewers comments I saw that they picked up on some of my points which gave me the confidence to stick to my guns and write anything I felt was important to say.”

How do you decide when a patient review should be included?

We invite patient reviewers for most research papers, particularly those where patients were recruited into the study reported, but we recognise that it is not appropriate for all papers. For example, we don’t routinely invite patients and carers to review methodological research papers or journalology papers.

How do you recruit patients and carers to be reviewers?

We have done this in various ways with the help of our patient partnership panel and patient editors who have been a constant source of advice and support for outreach to patients and carers via their own networks and linked communities. We also reach out to specific patient groups and organisations. To make our readers aware of the initiative, we have embedded an invitation to our readers to extend our invitation to review papers to the patients they see. The database continues to grow organically as patient reviewers share with their own networks. Our registration form and guidance are available here.

How do you evaluate their qualifications?

We welcome all patients and carers to review for us, and there are no pre-conditions for joining the database. We are interested in their lived experience of illness, medical interventions, and treatments, and also any advocacy work they undertake for fellow patients. We do not ask them to critically appraise/comment on the validity of the studies reported but they are very welcome to do so. Their comments are taken into account along with peer reviewers’ at the internal meetings where the BMJ editorial team decides which papers to publish or reject. All reviewers, including patient reviewers, are asked to declare any competing interests.

Is there now a core group of patients for the common conditions medical research covers?

Most of the 700 patient reviewers registered are people living with or caring for people with long-term conditions, but we also have patient reviewers who are happy to comment on acute conditions and broad-based medical issues such as patient and carers’ experience of accessing and using services, their involvement in decisions about how services are designed and delivered, priority setting in health care, and ethical debates. We do of course make it clear to reviewers that they are free to decline invitations to review.

How have authors accepted having patients as reviewers?

Feedback from our patient reviewers tells us that authors are responding courteously and constructively to their points when revising their papers. We plan to carry out a formal evaluation of papers reviewed by patients and carers to see the sorts of comments they are making and how authors are responding, and we will do this alongside an analysis of the response to peer reviewers’ comments.

Have review times increased with patients involved?

Not at all. We have implemented patient review so patient reviewers and peer reviewers are invited at the same time and both are asked to submit their reviews within 14 days. The average interval between invitation and submission for patient review is slightly faster than for standard peer review.

Are acceptance rates different when patients review?

This is an interesting research question. We have not formally looked at this yet but may do so in the future. We would not expect to see major changes for editors’ decisions on whether to accept papers for publication which is based on multiple factors including originality, scientific robustness, and relevance for our readers.

You publish patient reviews along with the papers. Any issues doing this so far?

The BMJ has an open peer review policy whereby the authors’ and the reviewers’ identities are stated in the review. In 2015 we began to publish online, beside the published articles, the full pre-publication history for research papers, including the reviewers’ comments. We inform all reviewers that reviews will be published online. A few patients have asked to review anonymously, as have peer reviewers, and although we do not encourage this, we have accommodated these requests on a case to case basis. Our patient reviewer survey found (somewhat to our surprise) that most support open review.

If another journal were considering doing this, what advice would you have for them?

Our advice would be to “follow The BMJ’s lead.” Patient review of papers and patient and public involvement declarations are important steps along the road towards partnership and to facilitate research replicability. A few other journals have already begun this journey including Research Involvement and Engagement, CMAJ, and BMJ Open.

We find it essential to provide patient reviewers with clear guidance on what is being asked of them and to clarify why it is important. We suggest eliciting early and continuing feedback from reviewers, authors, and editors to inform and guide the process. Reviewers tell us they value feedback and information on the patient review initiative and, where possible, brief feedback on reviews they have done to help improve their confidence. Reviewers welcome receiving a year’s subscription to The BMJ and annual recognition on our website as a reviewer. The editors offer an annual award for Best Patient Reviewer, and patient reviewers are invited to join judging panels for The BMJ Awards. We also invite them as partners in our internal research, and to help us air the patient and carers’ voice by writing Patient Perspective articles for BMJ Opinion, contributing as authors to “What Your Patient Is Thinking (WYPIT)” which is a series owned, led, and edited by patients and carers. Our reviewers welcomed partnership and we advise other journals to consider the value of patients as collaborators and partners in their journals too.

This is a quote from one of our patient reviewers in our survey when asked if more journals should adopt patient review:

“This is cutting edge stuff right now. Now’s your chance to be at the front of this trend. It’s becoming more and more common, though, so if you don’t get in now, you risk being left behind. You don’t want to be the last major journal to adopt this important process, do you?”

Discussion

5 Thoughts on "Interview: The BMJ’s Patient Review Initiative — A Novel Expansion of Peer Review"

A study by Sara Schroter et al. on this was presented at the Peer Review Congress last year; just thought I’d point to it from the blog post (the link includes a video from the Congress):

https://peerreviewcongress.org/prc17-0103

“Introduction of Patient Review Alongside Traditional Peer Review at a General Medical Journal (The BMJ): A Mixed Methods Study”

A really interesting and encouraging article. Your readers might like to know that Cochrane (Cochrane.org) has been involving healthcare consumers (patients, carers, family members and service users) in the production of its evidence since 1984. Members of a network of 1700 consumers around the world contribute in a variety of way, most commonly by peer reviewing abstracts, plain language summaries and full Cochrane Reviews, but also helping to set priorities for research, developing research questions, identifying patient-important outcomes and working alongside researchers. Consumers contribute to the governance of the organisation. You can read more at http://consumers.cochrane.org/

Amendment. Since 1994.

I have been a consumer health informatics researcher for 16 years with some experience as a caregiver, but when I became a patient living with a serious illness myself about 3 years ago, it introduced quite a change in perspective. So when I saw the BMJ Patient Review Initiative advertised, I grabbed onto it with both hands. I’ve done 2 reviews so far and found it an interesting experience. The one caveat I’ve got, as a longtime academic article/book manuscript reviewer in the health sciences, is that the expertise required by the BMJ to review as a *patient* feels very different than the expertise journal editors require to review as a, well, reviewer. It’s a bit like getting a reviewer invitation for a manuscript in the field of early Victorian literature when your stated expertise is Czechslovakian modernist music: They’re both in the general basket of Humanities, but that’s all they have in common. I did have to ask some clarifying questions of the BMJ editors about that, but their responses were helpful and thorough, which made me feel better about the whole process.