Almost every day, my email or Twitter feed brings an alert to a “free” report, article, white paper, etc. No payment or subscription required!

It sounds great. In many ways it is the promise of the Internet fulfilled, a world in which a single click brings you the document you are seeking for immediate review or even a deep read.

The reader experience, however, is quite often not exactly that. Instead of a paywall, perhaps to be negotiated through a proxy server or some other authentication mechanism, the reader is faced with a demand for their contact information. Or, even more demanding, they face a requirement to create an account. Use of that account will be tracked and the data fed into an analytics system, likely joined up with data collected elsewhere as well.

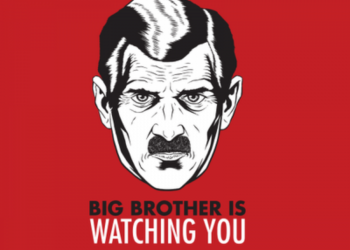

Yes, dear reader, in such cases, you have been datawalled.

I found myself thinking about this as I clicked the link in a tweet to read a review of the movie Paywall: The Business of Scholarship. From the tweet I saw, I was expecting the text of the review to appear. Instead, given the review was published in The Lancet, there was a demand to create an account (or use my existing one if I had one). Given the topic of the movie, I couldn’t resist tweeting out “LOL. Review isn’t OA.” More than one reply came back observing: yes, but it’s free.

True, Elsevier tells you this straightforwardly on the page you encounter: “This article is available free of charge. Simply log in to access the full article, or register for free if you do not yet have a username and password.”

Well, sure, the article is “free” in the sense there is no monetary transaction. But, not free in the sense that I must trade my time and my personal information in exchange for the access. And, I must consent to account terms — e.g., data tracking, analysis, reporting — that I have no mechanism for negotiating. Instead of a paywall, I face a datawall.

Now, of course copyright owners of “free” resources have the right to set the terms of access. They can put up a datawall that demands the exchange of personal information (and thus enables data tracking, reporting, and maybe even aggregation with other datasets) for an otherwise free article.

I wonder how far we will see this extend.

There are already examples of “freemium” open access in which basic reading is available without providing contact information or having an account but other kinds of reading (e.g., downloading full document for annotation) is behind a datawall or paywall.

In preparing this essay, I reviewed a number of publisher websites and government policy documents. Absent from these is mention of whether “free public access” or “APC-funded open access” means access without providing a contact email in exchange or without being required to set up a (free) account. This is a curious silence. It leaves open a future in which publishers and platforms monetize open access through intense data analytics activity tied to user identities as well as APC fees.

With the strengthening publisher-based RA21 approach to authentication, the developing supercontinent of scholarly publishing, and the ever increasing trend to tracking and monetizing user data, as well as the silence on this topic in policy and contracts, personally, the question does not appear to me to be if public and open access publications will be pushed behind a datawall…but rather how quickly.

Discussion

22 Thoughts on "From Paywall to Datawall"

A thoughtful, provocative piece. Within the EU, another factor comes into play – data protection. Any organisation requesting personal data like this from an EU national needs to explain clearly how it will use said data, and will be open to demands from EU-based individuals to see a copy of records held on them, who such data has been passed to, demand corrections to inaccurate data, object to further processing of the data, etc.

How about Richard Poynder’s review?

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-06140-7

Are publishers truly unclear on “whether … “APC-funded open access” means access … without being required to set up a (free) account”?

OASPA membership requires that articles “can be read without the requirement for registration of any kind”

https://oaspa.org/membership/membership-criteria/

Likewise, “journals requiring users to register to read full text are not accepted into DOAJ.”

https://doaj.org/publishers

This is as required in the original Budapest definition: “By “open access” to this literature, we mean its free availability … without financial, legal, or technical barriers other than those inseparable from gaining access to the internet itself.”

https://www.budapestopenaccessinitiative.org/read

The only example of a registration barrier given here is from a paywalled journal. Likewise, the example of purported “freemium open access” linked to acknowledges that it is “not yet to the standards called for by many open access advocates, such as the Budapest Open Access Initiative”, i.e. not in fact open access. Glad I could clear that up.

Thanks for the info, though to be fair, there is no singular accepted definition for what exactly the term “open access” means (is a free article with a CC BY NC license “open access”, or is a Green article in a repository under traditional copyright open access? And just what exactly is bronze open access — is it open access at all?).

It’s a rabbit hole to try look for consensus on what is open access or even who has the authority to define it. If you aren’t concerned that we could see a shift to datawalls rather than paywalls, that is certainly one view. Personally, I’m concerned anytime an assumption is made about what a contract means when the contract is silent on the topic. If we want the contract to mean all forms of reading (and download, printing, etc.), it needs to say that. Precisely because terms like “open access” are not singularly defined.

While I agree that it is always valuable to help make people aware of how much of their privacy they’re giving away, is this a battle already lost? The vast majority of internet users seeking a report like this will be simultaneously signed in to Google and Facebook, and already having their activity tracked by dozens, if not hundreds of trackers. Does having one more company collecting their data, one more drop in the ocean, really matter at this point?

That I consent to some entities tracking me does not mean I consent to all entities tracking me. Maybe you don’t read terms of service/privacy policies but I do in many situations. I dropped a class this semester rather than be subject to terms of service/tracking/data re-use for a platform used in the course.

Right, and I agree 100% (and don’t use Google, have never used Facebook, and don’t use Amazon because my privacy is more valuable than the services they offer). But here aren’t you complaining about that very same thing? This publisher will give you an article if you consent to being tracked? Why is this somehow wrong or deceptive as compared to the hundreds of trackers that are following nearly every person on the web around all day every day? What is different here?

The issue I’m raising is a policy/contractual one. If funders (e.g., institutions, grant agencies, governments, libraries, departments, and even individual scholars) believe that they are paying for free, unfettered reading (including reading, download, printing, etc.) and in fact are not then there is a gap in the policy/contract regime.

I’m not raising a moral question – as I acknowledged copyright owners have the right to do what they are doing. I’m raising a question about what is and if that is what was intended. If it was intended, great. If it wasn’t, then action is likely warranted to align policy/contract with intention.

Yet this was a movie review, likely not a funded article. I suspect what one will see more is required registration for “personalization” and other advanced features, with bare bones access separately available as well.

Regardless, this is the (current) way of the world, whether we like it or not. Surveillance remains the internet’s most successful business model.

Yes, it is the way of the world it seems. And, I agree that we’ll probably see a baseline of open-for-reading. But, I think that baseline will be as restricted as possible (like the freemium models).

If you are a funder or otherwise open access advocate and that isn’t the world you want or thought you were creating, that it is the way of the world doesn’t mean you can’t seek to take corrective action. If we are trading subscriptions for APCs in the pursuit of open, it would be ironic if that openness isn’t what we thought we were buying.

Another way to characterize this paywall/datawall distinction might be to observe that the reader’s role has moved from customer to product.

In either case, someone has assembled an asset that has monetary value, and money still exchanges hands. In the paywall case, the product being sold is the work itself, whereas in the so-called datawall case, the amassed data is the actual product. And as luck would have it, the latter presently has the higher street value.

This is the root difference between inserting an implied “[…for free]” at the end of Google’s mission statement (as several of us recently heard at a forum, to which we responded with a collective groan) vs. a more accurate “[…because, dear readers, your eyeballs are surprisingly profitable].”

Just an observation, not a value statement….. 🙂

As a reader, I am now under constant surveillance. Most commercial publishers have an army of tracking cookies and analytics plugins. I can block a lot of them – at least my ad blockers show that they are blocking lots of them. But probably not them all.

When I encounter data-walled content, I do register, but I use a fake name, email address, and when possible, do so via a proxy server/VPN/Tor. I download whatever articles I want from that publisher and forget my login details. If I wasn’t going to pay $90 for a PDF, I am not going to give them my real personal information. And then there’s always sci-hub…

Being tracked is the least of it. Some publishers of “free” material want your credit card information as well as your name, “just in case” you also want to BUY something they publish. This, in my opinion, is fundamentally dshonest.

Along time ago I heard this summation of publishing business models (from a publisher): you’re either selling your content or you’re selling your audience. At the time “selling your audience” referred to advertising models, controlled circulation, etc. Now “selling your audience” has expanded to include more granular functions of data analytics, insight generation, and derivative products and services – and they all require some method of data collection. I suppose we can add selling your services to that too (not strictly content). Anything else to add or evolve?

Leave your Name and Email to comment …

Ha!

As far as I know, that’s required for the “Send me a notification of further comments” functionality of the site. But to be clear, we at The Scholarly Kitchen don’t do any tracking or reuse commenter email addresses (and with no verification step, half of them are things like fake@fake.com).

Hi Lisa. It goes beyond scientific publication. People are realizing here in Brazil how harmful the paywalls in big news media are – by making it harder to access and prevent people from reading dense materials and investigative journalism they are counteracting by the increase of false content in whatsapp (major force in presidential elections here). Newsmedia are not taking responsibility, they could just overturn the paywalls, but it seems they are concerned about that kind of engagement you mentioned above – clickbaits