Are the humanities down for the count? Big declines in majors, unable to compete with the ascendance of STEM, unable to stem the worldwide degradation of liberal democracy — which was, after all, the seedbed of humanistic scholarship in the modern west: the situation seems dire. The fate of Stanford University Press (SUP), its Stanford University funding imperiled, seems like a parable of the fate of the humanities. And it may yet be, though maybe not, and maybe not for the reasons we think.

The situation brings together a predictable mix — perhaps a toxic cocktail — of recent phenomena affecting the humanities in higher education. An upper administration with a STEM bent, the invocation of business-style accounting to assess scholarship and scholarly programs, and more than a whiff of uptempo resistance to collective investment in the collective good. The short version is that Stanford’s Provost, physicist Persis Drell, proposed cutting the press’s subsidy of $1.7 million in the interest of creating a “sustainable” and “right-sized” press.

The details are a bit more gruesome. SUP’s clashes with the Stanford administration have been widely reported and discussed, here on the Scholarly Kitchen, in higher ed media, and mainstream media, including on KQED, San Francisco’s NPR station. The SUP total annual budget is $7.7 million, with $5 million in revenue. The university’s subsidy, it has been pointed out, is a tiny fraction of the overall university budget. So what was the point? Some have suggested that the Provost meant to shutter the press entirely, though she has denied that. Without clearance until very recently to do the kind of fundraising that underwrites presses at universities with extraordinary wealth comparable to Stanford’s, the loss of that subsidy, whether immediate or over a few years, would be devastating to the press’s operations.

But the Stanford community and the university press community roared back. With the motto “125 Years is Not Enough” the elegant website Save Stanford University Press “chronicles the ongoing situation.” If you have not seen it, take a look at the extensively linked timeline of events and coverage. It starts with April 26, and the Chronicle of Higher Education story on what sociology professor Woody Powell called “a reprehensible moment for one of the richest universities in the world and a diminution of intellectual inquiry.” It continues through to the Faculty Senate meeting last week in which graduate students responded to administration reference to using the savings from the press subsidy for graduate student stipends and “categorically reject[ed] this…false choice.” The site includes the letters of support from around the Stanford campus and from scholarly societies, as well as statements from the Association of University Presses.

The website also includes a page of “SUP Facts,” beginning with the press founding in 1892, at the request of the university’s first president in his first year. It is the oldest university press in the western United States. Like all university presses, it plays both a local and a global role. A university press serves the scholarly community writ large, by putting critical exchange into practice through intensive review of submitted work, and by producing revised and polished work. And in its local context, a university press is a key site for the culmination of intellectual exchange. It embodies, as the graduate students at the faculty meeting expressed it, “the values and knowledge we hope to create and disseminate.”

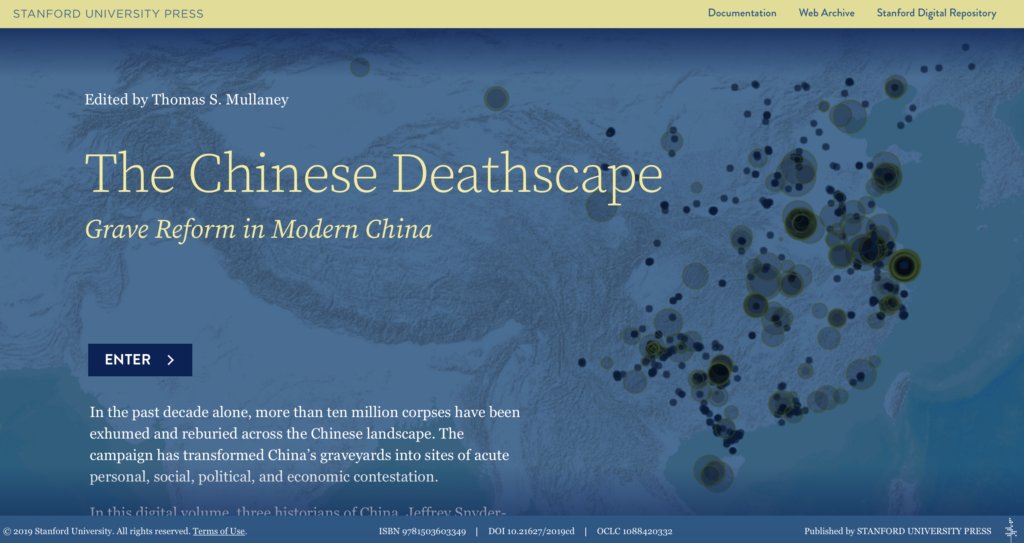

A group of faculty have been especially active on social media, in engaging news reporting, and by rallying the Stanford faculty senate. Among the most vocal is Tom Mullaney, professor of Chinese history. A prolific and highly regarded scholar, Mullaney has published with multiple presses, but brought his most recent project to his home campus press. The Chinese Deathscape is the result of his extensive research on the more than 10 million grave relocations in China in the last decade; he is joined by two other scholars in an interactive website that looks at the experience and implications of Chinese gravesites over several centuries. Published on a bespoke platform that was one result of a grant from the Mellon Foundation to SUP, Mullaney described the high quality of the editorial work that went into his publication. With an editor securing and then managing seven peer reviewers with content expertise and digital expertise, the press brought a top notch team to this work.

Not only as a Stanford history faculty member, then, but also a press author, Mullaney thinks the treatment of the press is indicative of a wider misapprehension of how diverse scholarly fields function. From the nature of research (where it happens, and how it proceeds) to intrafield sharing of research and interpretation (from modes of sharing to platforms for sharing) to reporting results (through publication of multi-authored, multiple short papers from one research project to single authored longform essays and books), scholarship looks very different from one discipline or field to the next. And when any one is presumed the standard, the variations suffer.

He’s not alone in thinking that a presumption against the humanities and social sciences is behind the proposed cuts to the press. A statement from Stanford Graduate Students in the Humanities and Social Sciences read at a packed Faculty Senate meeting June 13 noted that the episode and the administration’s responses had simply, “reaffirmed that this institution does indeed marginalize the humanities and social sciences — which seem to have value only insofar as they support STEM fields.” Even undergraduates are open about this tension, which is evident across campus.

The final determination of SUP’s fate is unclear. For now, the university has maintained the status quo in funding the press’s subsidy for another year. There are two university committees that will study the situation. One is appointed by the Provost, and is looking to external guidance on, “the optimal size of the press, its financial needs, its fundraising potential, its organizational structure, and its governance and reporting structure within the university.” The second was created by a resolution of that last, intense faculty meeting and its membership will be determined in the fall. At issue, in part, is what standing the university’s Committee on Libraries, which sponsored the resolution and has historically been involved in discussions about the press and its functions, will have in these deliberations. There will surely be many next chapters in this saga.

It is perhaps the perfect illustration of what the near-frenetic enthusiasm for technology and business has wrought that it is the university press in the shadow of silicon valley — from the university that has been the seedbed of some of the most important (and arguably, some of the most problematic) innovations of the past century — that is under the gun. The language of “right-sizing” the press, and the concern with “sustainability” that is surely not about quality — after all, SUP is making important contributions to knowledge with every publication — seem to be only about financial investments and returns. Is this what a great university does, is, and should be?

Right now Stanford is on the back foot after the intense support rallied for the press. But imagine this going a different way. What if Stanford used this opportunity to embrace what the humanities and social sciences are offering — not just about how to serve tech, but how to survive and thrive? What if the university mobilized the accumulating evidence about the fundamental value and values that are expressed by such eminent units as their own university press?

A flourishing critical scholarship on the scale and structure of media and technology companies has shown how a failure to incorporate basic insights from the humanities is impoverishing society. From Siva Vaidyanathan’s 2011 The Googlization of Everything (and Why We Should Worry) to Safiya Noble’s 2018 Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism and more, we see how both the business and the product structures of big tech can drive detrimental social effects that may overwhelm the positive goods they offer. Technologists themselves see this, and are expressing increasing alarm. The adage “not can we, but should we?” requires not only an ethical perspective, but insights from research in non-technical fields.

And beyond this growing recognition, it’s pretty easy to find analysis, anecdotal evidence, studies and surveys reporting that businesses most want the skills that liberal arts majors are taught: analysis, communication, and research. And what about the economics of a university? Internal analyses have been showing, from Robert Gates’s famous studies at Texas Tech and onward, that humanities courses can be subsidizing STEM course offerings.

There is, as a letter of support from the American Historical Association acknowledged, “a fundamental compact between society and its great universities to add to our store of knowledge in all its forms, including the extensive research and complex argumentation whose medium is scholarly books.” Stanford University has a unique opportunity at a unique moment to be forward looking and forward acting — to see in fact how the humanities maybe just what technology, Stanford itself, and its near neighborhood in Silicon Valley most needs. It could throw its arms around the humanities and social sciences and embrace what this historical moment most needs. Hug a university press today.

Discussion

16 Thoughts on "Stanford University Press and the Wrong Lesson of the Humanities"

A side-by-side comparison with the University of California Press might be instructive here: Neighboring university presses, affiliated with elite schools, established within a year or two of each other. And yet, the one affiliated with the wealthy private school seems to be struggling while the one affiliated with the public school seems to thrive. Seems like a curious juxtaposition to me.

There are so many ways in which that would be an interesting comparison— the geographical proximity and public/ private as you note. But I think there are deep issues less to do with the distinctive profiles of the presses —both excellent, but quite different— and more to do with the way they relate to their universities (one a full system, among other things) and the governance of same. Thanks for your comment—

My pleasure Karin. Thanks for your article. I’m mainly interested in the larger question of why some scholarly publishers succeed while others scuffle. I’m sure the answer would be much more complicated that “one published good books, the other not-so-good books.” SUP and UCP seem like fascinating case studies into this very question.

Yesterday at our Publishers Lunch at University Press Books/Berkeley we had at the table three executives of the University of California Press who had, in mid-career been asked to apply to be the director of Stanford Press, one having done so. Our bookstore has sold both press’s books for 45 books. Both have been top-tier publishers for all that time. Both have always had financial problems and had to solve them by seeking subventions. Both have suffered from clumsy executive decisions. Both have been blessed with powerful faculty support, which has beautifully come into force at Stanford in this kerfuffle.

Thanks for your comment Bill. UCP is significantly bigger than SUP though, right?

Methinks thou dost protest too much. Oh, the humanities! They won’t completely fade away (and I doubt they’d leap to the defense of their department brethren if the shoe was on the other foot). Sometimes downsizing really is rightsizing.

The problem with downsizing or rightsizing or whatever you want to call it is that it betrays a lack of understanding of publishing economics. Book publishers make money when they reach a certain scale. If Stanford Press were to reduce its title output, it would actually be losing more money than it is now. The real goal for the Press should be to get bigger, not smaller. The economics are different for an academic department, where cutting faculty positions leads to bottom-line savings. I am not defending any such action, but want to make it clear that there is no way to discuss the budget of the Press in the absence of an overall strategic assessment.

Agreed! And my agreement comes with an exclamation point because I know you mean a strategic assessment that is not just the finances but the other values at question.

Where are the alumni donations? Maybe they need to add a Press option to the Stanford Giving page, it sounds like the Press is seen as an afterthought by administration. http://giving.stanford.edu/how-to-give

Two comments: In a time of concerted attacks on liberal values in America led by its President, one would think that America’s liberal institutions would be pursuing a defence, and perhaps a strengthening, of all manifestations of liberal values including (outstanding) university presses. Second, one might expect generally supportive comments to this issue in a blog of America’s Society for Scholarly Publishing. Instead, we get doubters except for Joe Esposito’s reply. Makes me wonder.

Not certain how one could read Philip’s comment as one of doubt so much as wanting to delve deeper into the UCP vs SUP comparison.

Exactly. Thanks Alainna. One would think that the wealthy, private institution would be more likely to support a UP than a public, but equally prestigious, university. But it appears that assumption would be wrong. I’d be curious to know how the Provosts of both schools view the missions of their UP’s. And how committed they are to helping them execute those missions.

The financial problems at Stanford UP preceded my hiring as director in 1983. The Press had, for most of its life, included a printing and binding facility; recharges to other offices for all sorts of job printing furnished a modest subsidy to the Press. The last vestige of that operation had been removed just before I was hired. But University administrators continued to classify the Press as an “auxiliary enterprise,” which to their thinking meant that the Press was expected to be self-supporting. “All ships float on their own bottoms”: that was the watchword.

I had never promised that such a thing was possible; indeed, I campaigned vigorously to be included in the priorities list that governed activities of the University’s development office. I believed then, as now, that there are people who would gladly donate to an endowment fund that could be employed to subsidize books that could not earn their own way. The Belknap Fund at Harvard UP is the best example, but just one of many, of exactly that form of financial support at university presses.

It is worth noting that my boss at the time, James Rosse, the Provost, was an economist whose academic specialties included media. He left the University late in his career to become president of Gannet, the newspaper chain. He was, I think, opposed in principle to nonprofit enterprises. I recently wrote more extensively in the Chronicle of Higher Education concerning this history.

Grant, this is an unfortunate way of finding an old friend, but I can’t find another email address for you. I was just thinking of you because another edition of my book was just published and I was a little horrified to recall that I started writing it exactly fifty years ago. So, here’s to University presses! I don’t know if my email address will appear on this note, but, if not, maybe the Scholarly Kitchen can pass it along. Hope to see you again some day.

The humanities argument is persuasive; however, the economic argument is irrefutable: A $1.7 million annual subsidy to the Press is three-hundredths of a percent of Stanford’s annual operating budget. This is like $30 to a family making $100,000 a year. A doubling of the subsidy would not change the University’s financial position at all, but would ensure a healthy Press for many years to come.

Good idea: Double SUP’s University subsidy and unleash the staff and faculty to do necessary additional fund-raising. Stanford Press published 138 titles in 2015; California, 181; Princeton, 307; Oxford, 1500. On the “rightsizing” issue, the size of the University, or its wealth, has little to do with how large a press wants to be.