This is a disruptive moment for journal licensing. The value of the big deal has declined. When the value of a product declines, one expected outcome is for customers to drive down its price in the market. But something slightly different is instead taking place. Several major university negotiating groups, including those for Germany and the University of California, have cancelled deals with Elsevier, the result of failed negotiations. Some consortia have entered into “transformative” agreements with Wiley, Springer Nature, and others, including Elsevier. In this moment of disruption, I wish to focus on one growing if counterintuitive element of the library negotiating playbook: helping publishers prop up the value of their big deal bundles.

Assessing One’s Interests

For many libraries and consortia, the dilemmas and opportunities today feel significant. Many libraries are scrutinizing the value of their license agreements with greater sophistication than they once did. In the United States, in the wake of the failed Elsevier negotiation with California earlier this year, statements of support have come from libraries, faculty senates, and university administrators, even if there have as yet been no major follow-on cancellations.

Rhetoric aside, most libraries looking to seize this moment to rethink their approach are seeking more value in their bundles rather than a lower price to reflect the declining value of the core product. In some cases, this reflects a commitment to accelerating the transition to open access. In other cases, this may be a sophisticated recognition of publisher interests, as discussed below. In still other cases, it may derive from concerns about losing budget. Whatever the cause, the decision to seek enhanced value is notable.

Of course not all libraries face identical interests. Indeed the director of one major research library expressed relief to me this summer that their licensing consortium recently reached an agreement with Elsevier, avoiding the distraction from higher strategic priorities that would have come from a protracted negotiation if starting today. And more broadly, the university groups with the highest research output — like California — clearly face different incentives than those that publish less. Most libraries and consortia will be trying to determine their best individual negotiating opportunities in this moment of disruption, rather than all working from an identical playbook.

Understanding One’s Counterparty

As ever, the key to a successful negotiation is to understand the interests and limits of one’s counterparty. In the case of the global commercial publishers, in the near term they are motivated to ensure that revenue continues to grow and therefore margin along with it. They also must develop the fundamentals for longer term growth on both these metrics. Understanding how revenue and margin is reported publicly is essential, and this varies to some degree by publisher.

RELX’s annual financial statements and investor presentations are instructive, because Elsevier (in these materials sometimes called RELX’s STM unit) receives a higher percentage of its business from workflow platforms and tools (in other words, outside primary publishing) of any publisher. From these public materials, we can see that Elsevier’s results, for example operating costs, capital expenditures, and margin, are generally reported only in the aggregate. Revenue is detailed with somewhat greater granularity, through pie charts without accompanying percentage figures, covering world region, segment/format (i.e., print, electronic primary publishing, and databases and tools), and type (ie subscription vs. sale). Of course there are many subsidiary responsibilities for profits and losses in any large organization, but these can be adjusted internally. All this to say that while maintaining its overall revenue base is a vital priority, a publisher can have at least some room for flexibility in how that revenue is sourced — and therefore within a given publisher how products are bundled for a customer.

Libraries are coming to recognize that this can present an opportunity. Even though the economic value of the big deal has declined, publishers are trying to resist any form of outright price cut that will hit their revenues. Instead, they are looking to maintain or even grow their revenue by adding more value to license agreements as they are renewed. So libraries are asking publishers to look across the various assets in their portfolios, not only in platforms and analytics and tools but even in their primary publishing portfolios, and add them to the big deal bundle.

Flipping the Big Deal

There have been two fundamentally different approaches libraries have taken to increasing the value of the Big Deal. First is the most widely discussed form, the “transformative agreement,” which bundles open access publishing for affiliated researchers with reading rights to publications that remain available via subscription. A number of these deals have been struck in recent years. Although transformative agreements may not actually be in the academy’s best interests and raise troubling questions about how costs are allocated among member institutions, many publishing intensive consortia will continue to pursue these models.

Because of the long-term implications of a shift towards open access via transformative agreements, libraries have opportunities to play publishers against one another. In Germany, in Elsevier’s absence, the other major houses have seen mouth-watering opportunities to take market share from Elsevier — especially on the supply side in terms of article flow. And as a result, Germany’s Deal consortium has found opportunities to strike deals with first Wiley and then Springer Nature that might otherwise not have been possible. A consortium with the wherewithal to cancel one publisher may have greater opportunities to strike agreements on more favorable terms with its competitors. These dynamics not only raise questions about why Elsevier hasn’t been able to strike a deal in Germany, but also whether and if so in what form California will play these dynamics to its own advantage.

Expanding the Big Deal

Other higher education institutions and their consortia are less focused on extracting value through open access publishing services and therefore in some cases less interested in pursuing these transformative agreement models. Instead, they are developing a second strategy, seeking additional value in the form of assets that the publishers hold.

One particular flavor of this strategy is to bundle platforms and analytics and other tools with content. In some ways, this is an obvious approach, one that has been developing for years as an array of publishers acquire and in some cases build portfolios of workflow and analytics platforms. In practice, we can see this model in a license agreement that Elsevier recently reached with Poland, bundling not only Scopus but also SciVal with access to subscription scholarly journals.

Even if they lack the scale of workflow and analytics platforms, many other houses are probably just as able as Elsevier to build bundles combining these newer business lines with their subscription publications. Wiley can do this with Atypon (including RedLink) and Evidence-Based Medicine Databases, Sage with Lean Library and its research tools, Springer Nature with its databases and research solutions, and Taylor & Francis with its colwiz. There is some redundancy across the workflow and analytics platforms provided by the publishers (even more so if Digital Science’s portfolio were ever to be bundled with subscription content as part of the extended Springer Nature family), and redundant offerings should affect bundling models and negotiating strategy.

Of course libraries and their universities have every reason to be concerned over the long-term implications of ever larger bundles. There are real risks of lock-in from many of these workflow portfolios alone. And, in many cases the workflow and analytics tools are more typically licensed by another university office, such as the provost, chief research officer, or laboratory PI, rather than through the library, creating budgetary and decision-making complexity for a single bundle. As universities provide workflow tools to their researchers they should address these complexities and risks even if the vast majority have yet to do so sufficiently. Since combining subscriptions and workflow tools in a single bundle can only serve to increase the complexities and risks, libraries should seek to ensure the separability of the different components of any such bundle, along with other policy and licensing matters.

Some Publisher Considerations

Whether libraries propose to flip or expand the big deal, as was noted initially everything comes down to money. Publishers have long been willing to strike either kind of deal for the right amount of money. The real question at this disruptive moment is how much additional value they are willing to add into their bundles in order to maintain and if possible grow their current revenue base. Given that efforts to fight piracy and address leakage have been proceeding fitfully at best, publishers face a complicated calculus about whether and to what extent to spend down these other assets rather than seeing them as sources of growth. Publishers will take different approaches depending on their strategic positioning and assessment of the value tradeoff they will face.

To take one example, a publisher that has already gone to market with an integrated offering of workflow tools and platforms faces a different set of considerations for propping up its subscriptions than one that has more modest such investments or one completely left behind by these workflow businesses. And, even in the best case, is there enough value from these other assets to compensate for the declining value of the journal subscription?

Or, a publisher with a higher percentage of its revenue attributable to open access but a smaller overall market share may see more upside to flipping its big deals than might be the case for the market incumbent. Which houses see in open access an opportunity to develop a second long-term source of publishing revenue, and which instead see transformative agreements as an opportunity to increase their market share of article supply?

Both in flipping and in expanding the big deal, publishers generate value in cases where they may as a result forego future revenues. In some cases, they will be foregoing revenue for tools they have already brought to market — and in other cases where they have not productized an asset that has as yet been dormant. Against this backdrop, publishers may well be able to maintain their revenue bases and ensure a rosy near-term story for Wall Street. But, will they have obscured the decline in value of other parts of their product lines? And will it be clear that they have cannibalized what might otherwise have been seen as their strongest long-term growth opportunities?

Looking Ahead

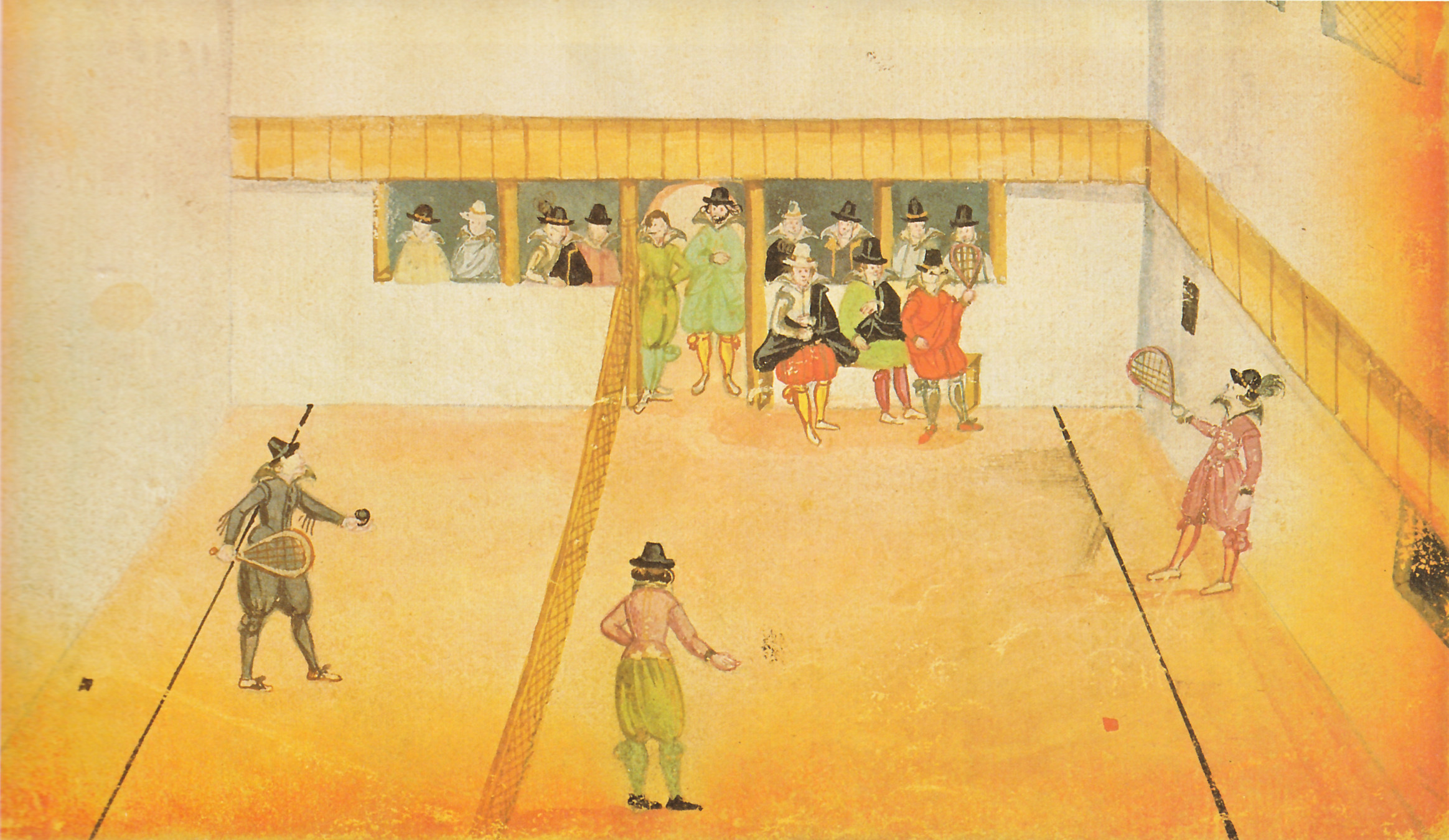

Many libraries are using a negotiating playbook that would, if successful, prop up the big deal in this moment of disruption. Is this the best approach for the academy? It is not the only possibility. Are there opportunities to seek price cuts and not simply value enhancements? Where might it make sense for libraries to develop productive alliances with one another and perhaps in some cases with preferred suppliers? How should they best map out and sequence their efforts? Sophisticated libraries and consortia have tremendous opportunities as they write a new playbook. The ball is in their court.

Discussion

1 Thought on "Will Libraries Help Publishers Prop Up the Value of the Big Deal?"

Appreciate this nuanced posting. You wrote, “Of course not all libraries face identical interests,” and that’s a key point here. Today’s headlines are naturally going to the groups that negotiate large transformative agreements, because these represent new and thoughtful, creative attempts to change the access and business underpinnings of certain (often the biggest and most costly) publisher contracts. Such experimentation is hugely important, and I daresay we will see many adjustments and re-thinking over the coming years; we’re not at the end state by any means (read SK in 10-20 years). But, to restate the point: consortia and libraries that have other goals or even wish to maintain the current arrangements but with more cost containment, shouldn’t be overlooked, marginalized, or criticized for lack of imagination. We’re reaching a stage where the previously more identical type of “big deal” arrangements are becoming far more varied to meet different situations, and that’s a Very Good Thing.