This is a guest post by Rob Johnson of Research Consulting and Vanessa Proudman of SPARC Europe. Drawing on a recent survey of European funders commissioned by SPARC Europe, they explore what European funders are doing to drive change in scholarly communication, and argue that funders’ open policies could be backed up more by funders’ own practices.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Research funding organizations are the life-blood of research and innovation; they are uniquely positioned to influence and fundamentally shift publishing practices and in turn maximize the impact of research. Active engagement by public bodies in the scholarly communication system is not without controversy, however, as the response of some scientific societies and journal publishers to a rumored US Executive Order expanding the requirements of an already-existing policy on public access to federally funded research and open data shows. While some stakeholder groups see such initiatives as an unwarranted intrusion by government agencies into the private marketplace, many others have argued for such a policy change, noting that the ‘scholarly publishing landscape can be meaningfully changed only if the funding agencies take the lead and initiate change.’

Attention in the publishing community tends to focus on the ‘big hitters’ of the research funding world. The publication policies of bodies like the US National Institutes for Health, the National Science Foundation, the European Commission and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, alongside private mega-foundations like the Wellcome Trust and Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, inevitably attract headlines given their considerable budgets. Yet it is important to look beyond the usual suspects to fully understand the direction of travel within the research policy landscape. Within many national contexts, a single government funder of research wields enormous power over the research environment, while even the smallest charitable trusts are at liberty to set the terms of acceptance for their own grantees. In research, as in so many other spheres of life, he who pays the piper calls the tune.

Surveying the landscape

As a longstanding voice advocating for unfettered access to research and data in Europe, SPARC Europe has a strong interest in the role of funders in driving open science. In consultation with Science Europe – the association representing major public organizations that fund or perform research in Europe – the European Foundation Centre (EFC) and ALLEA, the European Federation of Academies of Sciences and Humanities, SPARC Europe therefore launched a survey in 2019 of funders’ current policies regarding open science, exploring to what extent they reward and incentivize their researchers to adopt open practices.

The survey, which was mainly sent out to the members of Science Europe, ALLEA and the EFC, targeted about 400 European funders, and garnered just over 60 responses from 29 countries. The response cohort includes important national funding agencies (almost 50% of the respondents), pan-European funders (the European Research Council and the European Commission), national and regional academies, foundations and philanthropic organizations, and research charities. Note that the numbers do not show the difference between funder sizes. Survey questions explored funders’ policies on open access (OA) to research publications and data, the availability of funding for the dissemination of research, evaluation criteria for grant applications and research outcomes, monitoring and compliance arrangements, and planned policy changes, including their position on Plan S.

Survey participants were self-selecting, and thus the responses are likely to be biased towards those funders who are favorably disposed towards open science. The aim was to provide insights into the direction of travel in the European bloc, with open access defined as: ‘the free online availability of research articles, books, or other published content, combined with licensing that allows reuse with limited or no restrictions’. The findings may therefore not be transferable into other regional contexts such as the US, where Federal public access policies have hitherto been less prescriptive than those of their European counterparts.

A one-way journey?

The survey findings and accompanying dataset confirm some existing notions on the state of open science policy in Europe. The overall direction of travel is very much in favor of greater openness, but national and international funding agencies are far more likely to have open access policies than national academies or charitable foundations. Meanwhile, funders based in North and Western Europe have to date tended to place more stringent expectations on their grantees than those in the South and East. Research data policies still lag some way behind those for open access to research publications, with 61% of the sample reporting an OA policy but 69% reporting no data policy.

Other findings are less predictable, however. While most funders either already have an OA policy or are working to develop one, our work exposes a long tail of funders, many of which are private and charitable foundations in medicine and health sciences, who currently demonstrate only a marginal formal policy commitment to open practices. Four of our respondents stated outright that OA is not a priority for their organization – though it is likely that a much higher number would be found in this category amongst non-respondents – while others simply lack the resources either to develop or to implement and monitor a policy.

Matching policy with practice

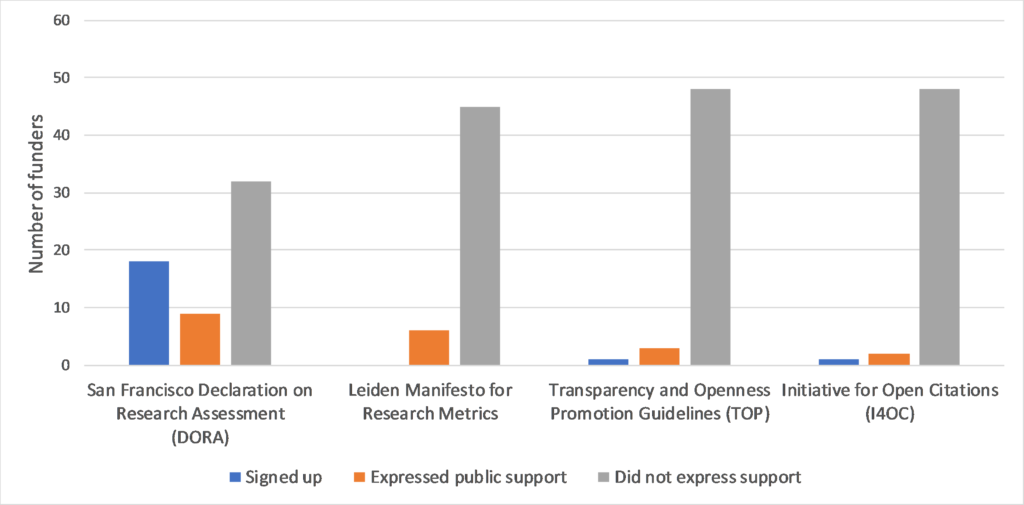

Interestingly, digging a little deeper into the data exposes a gap between the expectations placed on grantees and some of the funders’ own open practices. When considering how open science features in grant evaluation processes, although some funders offer a wide range of evaluation criteria, most are largely continuing with traditional ways of evaluating their research, with just under 20 still using metrics like the Journal Impact Factor. This said, an appetite for broader change does exist, as evidenced by 27 funders reporting having signed or expressed public support for the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA). Only seven funders, however, report using open science grant assessment criteria. At the time of the survey, it was Italy’s Compagnia di San Paolo, Belgium’s FNRS and the UK’s Wellcome Trust who went furthest in this regard, stating that, barring agreed exceptions, they will only take compliant OA publications into account when evaluating the track record of a grant applicant. Four other funders report considering all outputs, but attach additional weight to compliant OA publications. For the moment, these organizations remain the exception rather than the rule but it seems likely that other funders will follow their lead in the coming years. Somewhat surprisingly, 14 respondents reported not having any formal set of evaluation criteria.

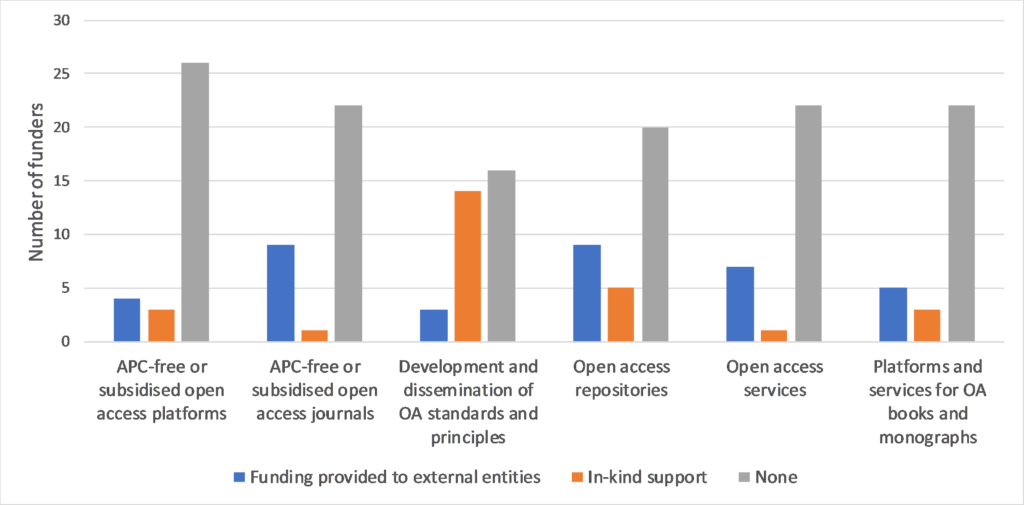

Furthermore, some respondents with open access policies neither engage in offsetting deals, provide publishing platforms or journals, or invest in open access or open science services or infrastructure, all of which are means to support and implement these policies in practice. While almost 90% (33 out of 37) of the organizations with an OA policy support the payment of publication charges, only three, the Austrian Science Fund, Parkinson’s UK and the German Akademie der Wissenschaften in Hamburg, reported (in the spring of 2019) that more than 75% of their research outputs benefit from this support.

As far as funding scholarly communications infrastructure for publications and research data is concerned, certain funders in Europe are making considerable investments in general research infrastructure, and in projects to help innovate the scholarly communications system. However, there seems to be a lack of funding for projects that have matured and have become infrastructure or services. Only a minority of respondents were actively contributing financially, though there is significant in-kind commitment to the development of standards and principles. In spring 2019, it was the Austrian Science Fund who reported investing financially in the broadest range of infrastructure, while the Swiss Academies of Arts and Sciences and Portugal’s Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia provided the widest range of in-kind support for OA. Examples of funded infrastructure for OA to publications include APC-free or subsidised open access platforms, APC-free / subsidised OA journals such as OLH or SciPost, OA repositories such as EuropePMC or arXiv, key OA services for articles such as SHERPA or DOAJ, or platforms and services for OA books and monographs such as OAPEN, Knowledge Unlatched or OpenEdition.

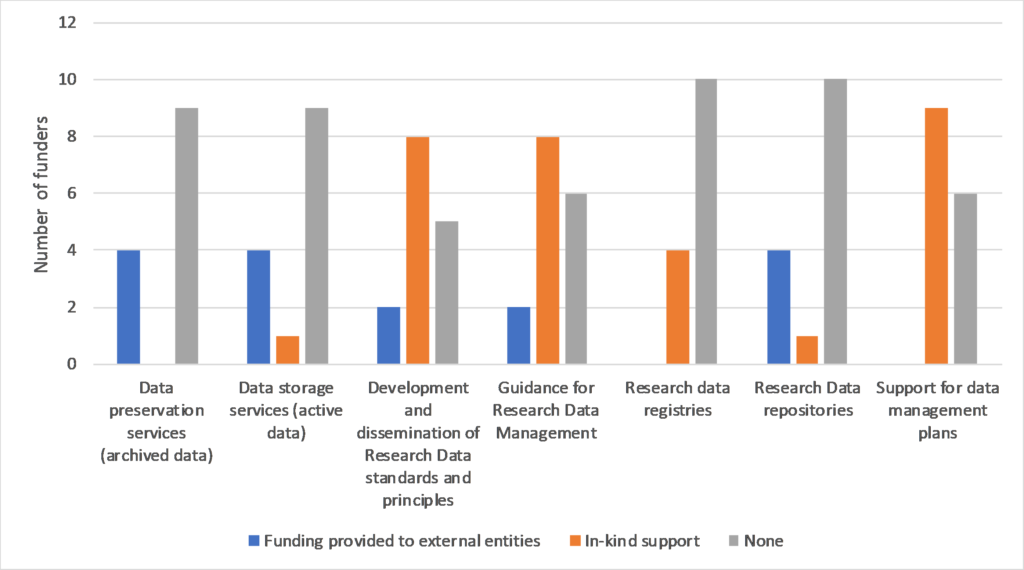

For research data (RD), far less funders with an RD policy report supported any of the following: the development and dissemination of research data standards and principles like FAIR Data, data preservation services, data storage services, guidance for research data management such as UKDS guidance, research data registries such as re3data, research data repositories or support for preparing data management plans. As with OA to publications, we see funders contributing most to the development of standards or guidance through in-kind contributions. In spring 2019, the funders who reported funding the widest range of research data infrastructure/services were the Swedish Research Council and the Swiss Academies of Arts and Sciences. Those who contributed the wider range of in-kind support to RD infrastructure/services were the Royal Irish Academy and the Austrian Academy of Sciences.

What does the future hold?

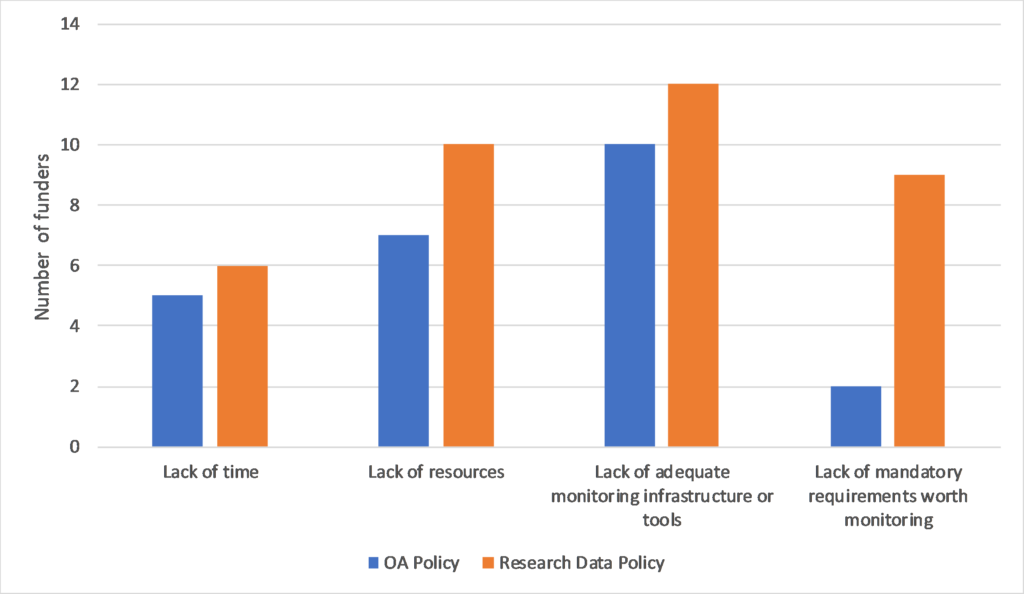

The survey data points to an evolving and potentially more demanding European policy environment. Of the 37 funders with existing open access policies, most had released or reviewed them within the last three years, and over half expect to review them again within the next 12 months. While many funders already have some mechanisms in place to monitor OA compliance, others reported lacking the time, resources, infrastructure or tools to do so effectively.

When asked what funders would expect their next policy reviews to focus on, respondents highlighted a desire to strengthen monitoring and compliance arrangements, as well as reviewing embargo periods, the eligibility of hybrid journals, licensing specifics and the role of caps/limits on APC expenditure. Research data policies are similarly in flux, with most up for review within the next three years. Future revisions to research data policies are likely to emphasize compliance with the FAIR principles, offer increased levels of guidance and support, and endorse the EC’s approach of making data ‘as open as possible, as closed as necessary’.

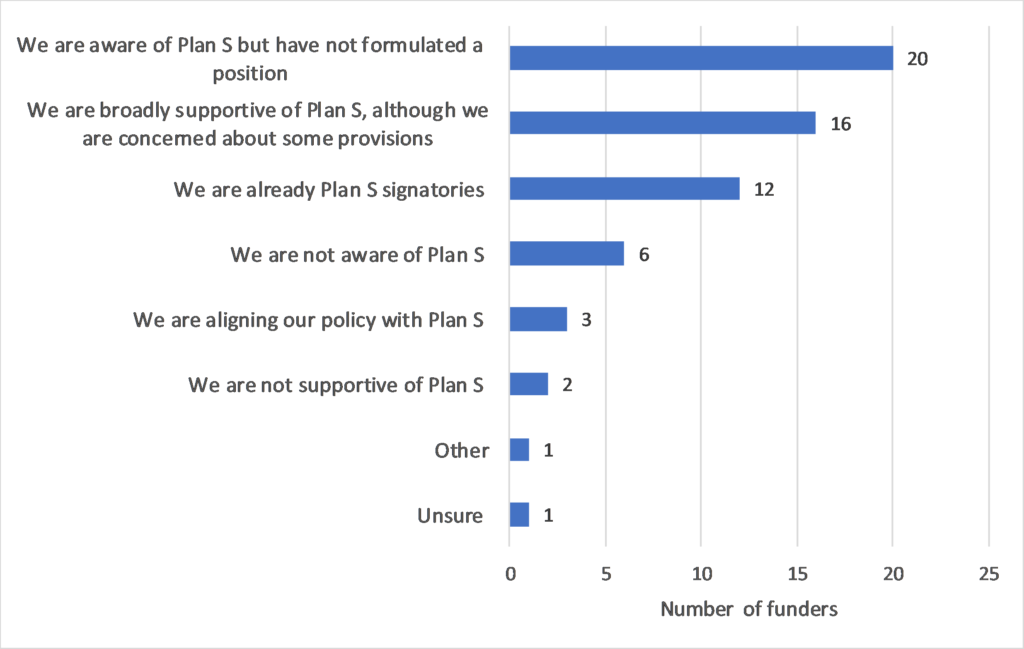

European funders were also asked to describe their organization’s position on Plan S. As of spring 2019 (prior to publication of the latest Plan S guidelines and requirements), 12 out of 61 respondents had already signed up to Plan S and a further three were aligning their policy with it; only six funders were unaware of Plan S and only two stated they were not supportive. Of the remaining 38, the majority had yet to formulate a position at the time of the survey (spring 2019), though positions may well have shifted since that time. Others expressed broad support for the Plan’s overall aims, and for open access in general, but with reservations about some elements.

Figure 5 European funders’ positions on Plan S (n=61)

Plan S undoubtedly had strong advocates amongst our respondents, particularly amongst existing signatories such as the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), who commented: ‘15 years after the Berlin Declaration, signed by over 600 institutions, the goal of 100% Open Access is still a long way off. Plan S revives the debate on achieving Open Access within a foreseeable timeframe’. Analysis of the accompanying free text comments suggests there was no single sticking point that was holding other funders back from adopting the Plan. Respondents variously cited timelines, costs, a perceived deprecation of green open access, impact on national research competitiveness, and a lack of wider consultation, though none of these were mentioned by more than three funders. Some noted uncertainties over the Plan’s implications, or a conflict with existing national policies, but indicated an intention to align policies where possible. One other funder suggested they would be unlikely to adopt the Plan’s principles any time soon: ‘Plan S is too radical for our country’s research environment and publishing tradition.’

The results suggest that cOAlition S could attract more signatories from the European funding community with time, and that it has had a galvanizing effect within that community that extends well beyond the current signatories. Despite this, many European funders appear content to be ‘fast followers’ rather than ‘first movers’, letting cOAlition S members take the risks associated with radical change. Growth in cOAlition S over the last few months has been positive, and it now boasts 24 members from across Europe, North America, Africa, and the Middle East, but more support will be needed to maximize its potential impact.

A call to action

Funders are embracing open science and rightly asking more of authors, institutions, and publishers in support of the move to open science. Irrespective of individual funders’ positions on Plan S, our findings illustrate two clear needs:

- for more policy development where it is lacking; and

- where policy does exist, greater alignment between policy and practice, and between countries.

However, funders could do even more to ensure their own practice matches their policy aspirations. This means investing in open scholarly communication infrastructure, scrutinizing publishing expenditure, including open criteria more in evaluation processes, and becoming active signatories and proponents of initiatives designed to promote responsible use of metrics, such as DORA, the Leiden Manifesto, and the TOP guidelines. To end on an important note, 90% of all respondents felt that making open access the default for the good of research was important or very important. We hope that this study will stimulate more funders to develop Open Science policy and to incentivise Open Science in the years ahead.

Discussion

4 Thoughts on "Guest Post — An Open Agenda: European Funder Approaches to Open Science"

Thank you for this very informative post. We just finished the 15th APE Conference in Berlin and I recommend to have a look at video recordings of Jean-Claude Burgelman (European Commission), Mark Schiltz (Science Europe) and a whole Session about the Transformative Agreements (DEALs) with Wiley and Springer Nature. http://www.ape2020.eu

As a participant of APE I can confirm these tanks were very informative.

Consequently, what I am missing in this post is what Jean Claude Burgelman eloquently confirmed – opennes for most funders appears to be a means to an end, not the end itself. It would be interesting to analyse how this agenda informs their policies in turn. But maybe that is the basis for a sequel to this article. Thanks to the authors in any case for such an informative survey.

Thanks for the comment, Andrea, I think that is a really important point. A meeting in London yesterday convened by UK Research and Innovation (one of the funders represented in our survey) to launch a consultation on its new open access policy shed some light on this. Funding body representatives there emphasised the importance of what they called the ‘public benefit test’, which I took to mean ‘taxpayers have the right to read the outputs of research they have funded’. They further argued that this test is applied independently of, and takes precedence over, disciplinary norms. Public benefit was therefore presented as the rationale for requiring open access monographs as well as open access articles, albeit over a longer timeframe, despite the many challenges associated with the former. They also noted a desire at government level to better understand the economic impact of existing and proposed open access policies, including whether these could be economically damaging (with this ‘damage’ primarily defined as a loss of tax revenue to the UK Treasury). Funders are being more and more vocal about the importance of making their research open, not for the sake of open itself, as you point out, but to use open as a vehicle to increase research impact and speed up innovation. Funders and institutions are asking publishers to play a role as suppliers in support of this goal; they in turn need to review and adapt on various levels to meet funder, institutional and researcher needs.

How will these efforts ensure that the diversity and quality of science will be preserved? The argument assumes that funded research is quality research, bias free, equally distributed and sufficiently abundant. If libraries step out and funders take over, the overall scientific endeavor will suffer. And as a society we will all be poorer for it.