One question that consistently vexes journal editors is the effect of their policies on submissions. Will authors take their best work elsewhere? Will we attract an avalanche of cookie-cutter dross? Will the new policy improve the quality of the articles we receive or just create an administrative headache?

The policy that has caused the most angst over the past decade is mandatory data sharing. It is well established that policies ‘recommending’ or ‘encouraging’ open data do very little to increase the proportion of articles that share their data, whereas mandatory policies that require data sharing as a condition of publication are generally more effective. It’s also well established that most researchers don’t really want to share their data, so bringing in a strong data sharing policy may persuade many to submit to a competitor journal. But is this really a concern?

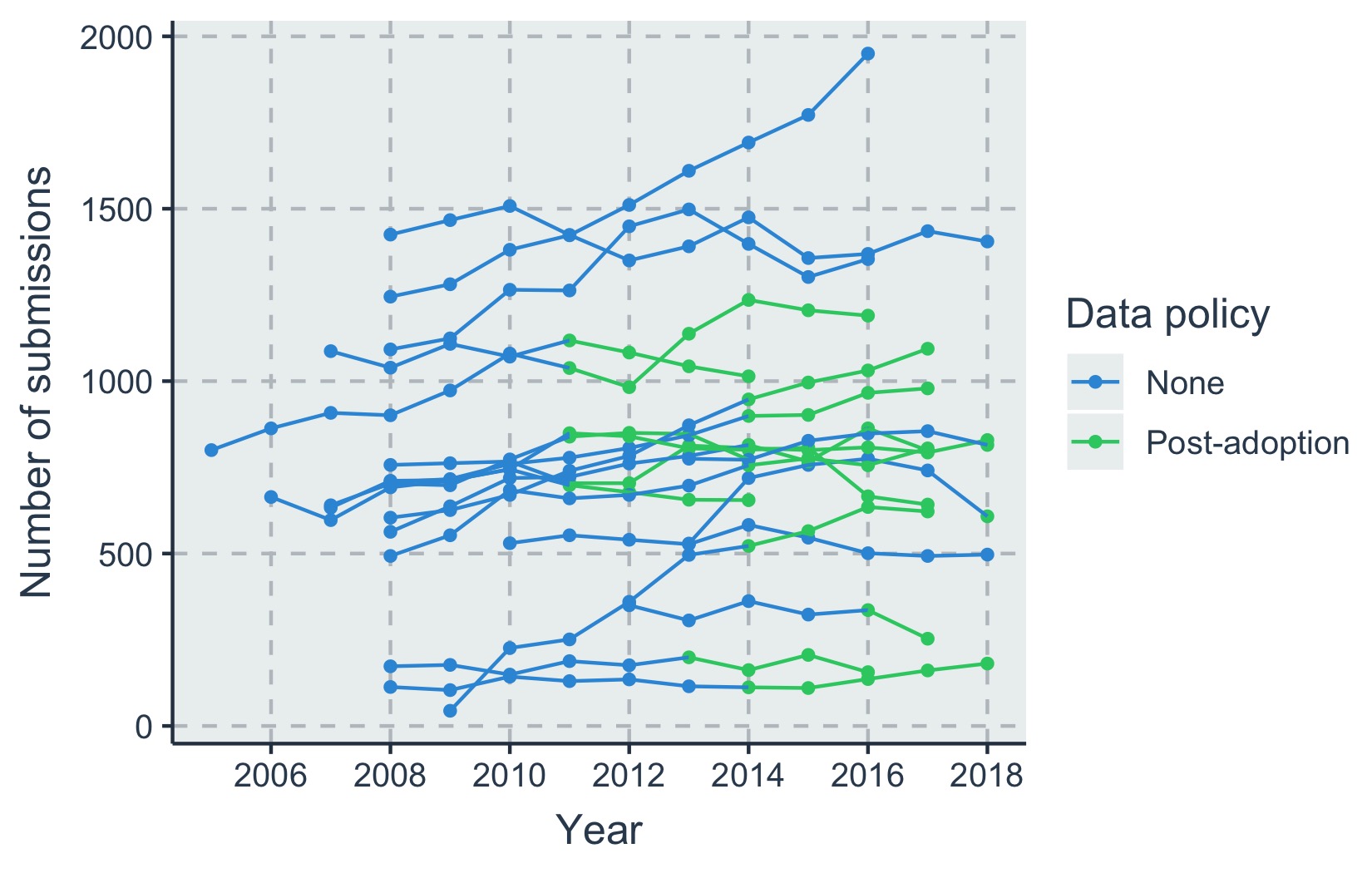

We’ve been gathering data to investigate how bringing in a mandatory data sharing policy affected total submissions to journals in ecology and evolutionary biology*. Some journals in these fields adopted the Joint Data Archiving Policy (JDAP) in 2011, while others adopted data sharing policies more recently, and still others have no data sharing policy. We posted our initial analysis on The Scholarly Kitchen a few years ago, but criticism in the comments on that post lead us to collect additional data on journals with no policy and revisit our analysis approach.

We’ve now obtained submission data from 15 journals for (at minimum) the four years before and four years after the JDAP (or similar policy) was brought in. For journals that had only recently adopted a policy or had no policy at all, we requested submissions data for 2011 to 2018. We used a discontinuous time-series analysis to see if submissions to journals changed over time, and if this was affected by introducing the JDAP. We also controlled for Impact Factor over time, as this may also affect submissions. The average IF across all journals and years was 5.3, with a minimum of 1.7 and a maximum of 17.9. Most journals showed only small increases in IF over time with some annual fluctuation.

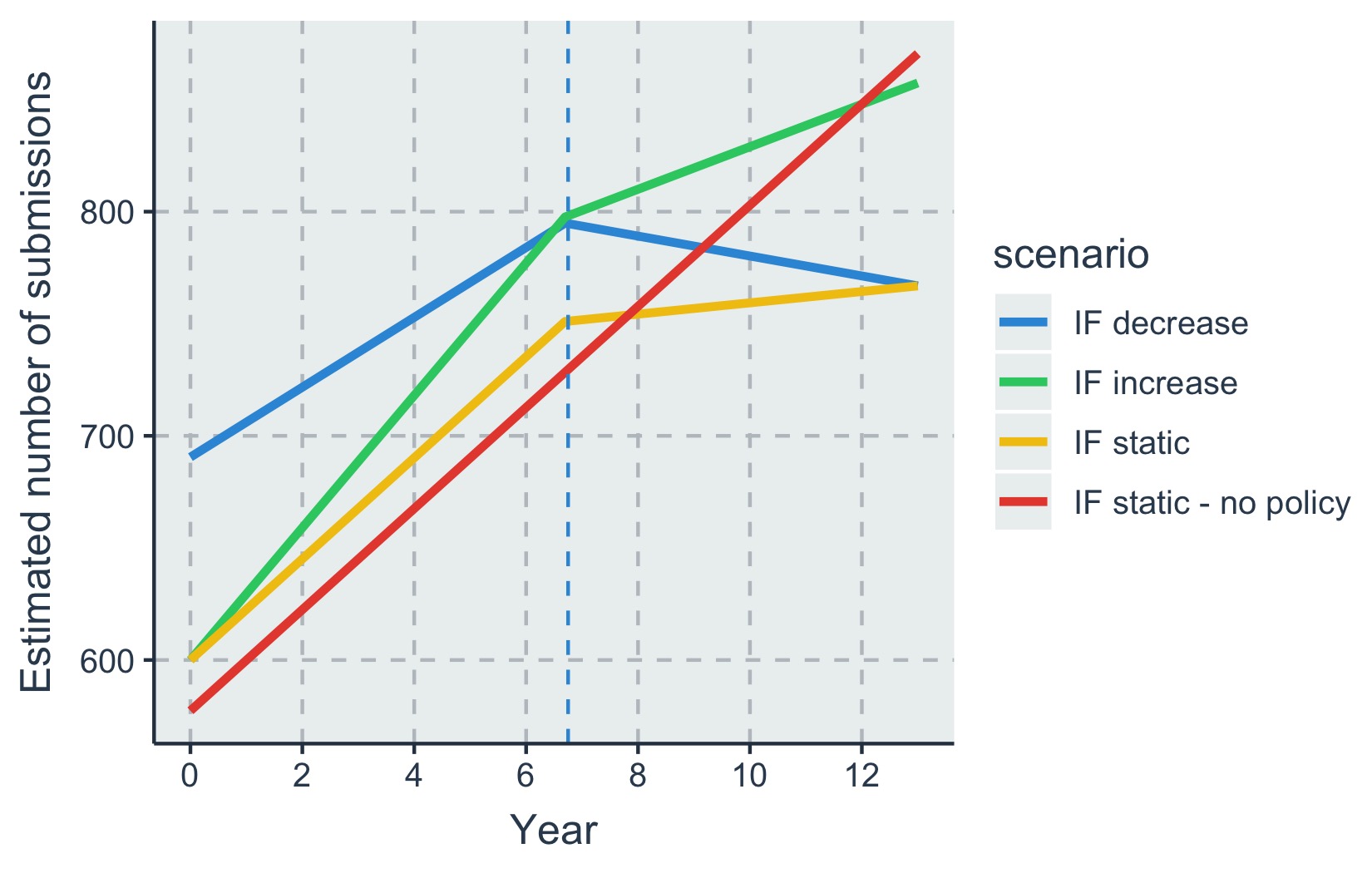

The results of our modeling indicate an ‘average’ journal with no JDAP saw a modest increase in submissions over the time period. Adopting the JDAP negatively affected submissions, although the scale of this effect depended on how the journal’s IF was changing:

- A journal with a rising Impact Factor also has rising submissions. Unless the increase in IF is large, adopting the JDAP slows the rate of increase of submissions per year.

- A journal with a steady IF would expect submissions to more or less level off upon adopting the JDAP.

- A journal with a falling IF would see a decrease in submissions upon adopting the JDAP.

- A journal with variable IF would have submissions going up and down over time with the amount depending on whether it is pre- or post-JDAP adoption.

These results do contrast with our original conclusions, which found no strong evidence for an effect of the JDAP. The difference here is that we control for changes in Impact Factor (which also affect submissions) and make a more explicit attempt to account for effects driven solely by the passage of time. As an example of the latter, submissions to Open Access megajournals (particularly PLOS ONE) rose steeply between 2010 and 2018, siphoning a growing number of submissions away from some of our focal journals as the decade wore on.

Journal editors clearly have to consider much more than just raw submission numbers – their goal is to find publishable articles, and having a mandatory data policy may or may not be helpful. For example, authors with low quality datasets and weakly supported conclusions may be deterred from submitting if they know that others will be able to examine the data (which is a good outcome). On the other hand, authors working on long term study systems may also go elsewhere because making the data public could severely undermine their ability to produce future work.

It’s possible that worries about the effect of data policies on submissions just reflect a moment in history – the decade where we moved from very few journals having data sharing policies to almost complete adoption. These results also quantify another feature of journal publishing: a journal that’s growing and gaining citations is much better placed to bring in potentially unpopular policies than one that is struggling. Ultimately, Chief Editors who care about promoting quality research may just have to take the plunge and bring in mandatory data policies, regardless of the effects on submissions and regardless of what their competitor journals are doing.

*We are very grateful to the Chief Editors and Managing Editors at these 15 journals for their helpful advice and cooperation with this project. Given the sensitive nature of submission data we’re unable to make the dataset publicly available, but please contact us if you have questions about the data.

Discussion

2 Thoughts on "The Effect of a Strong Data Archiving Policy on Journal Submissions (Part II)"

Tim, this is really interesting work and you have come to the discussion (as always) with data in hand. Nevertheless, I do wonder whether a regression analysis of 15 journals can tell us, especially when you’ve attempted to group these journals into 4 categories and use a covariate (IF) that may not be randomly associated with the intervention (data policy) or the effect (submissions).

Using a more general statistical analysis–the interocular test (i.e. eyeballing the data)–there appear to be two or three journals that may be driving the trends you report. Can submission data from these journals be explained in ways other than data policy, for example, changing its scope or business model? Do you have counterfactual examples to the general trend, and if so, what appears explains them? Can the editors of these 15 journals provide a narrative to explain their own trends? I realize that this kind of analysis is a case-based approach, but it may uncover deeper explanations and caveats on the effects of implementing a data policy. Your general conclusion: Data policies may have a negative effect on low-impact journals, but little or no effect on high-impact journals is probably still correct.

Hi Phil. Thanks for the comment. I agree that the generalizability may be lacking when we consider 15 journals, but we haven’t actually split them into 4 categories. Each journal provides data for estimating the slopes both before and after policy introduction (if there is one). The ones that did not have a policy introduced are used as data for estimating the slope over time (year) without any policy in addition to the data from each journal before policy introduction. The 4 scenarios in the figure are only 4 possibilities of variable combinations. Many more are possible, but we didn’t estimate their trajectories.

IF may indeed be related to both submissions and IF which is why it was included as a confounder (moderator) of the relationship between time and submissions.

Tim would have to look into whether we have any other inside information about the journals that may explain their differences in trajectory. We were hoping that some of that variance would be captured by IF changes over time, but obviously there are many other possible contributers that we have not accounted for here. It would be amazing to have data from more journals, but it’s hard to get submission numbers.

I agree that the general conclusion likely holds, and that provides some weight to these results as they are logically what would be expected.