Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Violaine Iglesias. Violaine is CEO & co-founder of Cadmore Media, the first video hosting platform dedicated to scholarly information. Cadmore’s vision is to provide the best on-demand streaming technology and service to scholarly and professional organizations so they can publish media content in the same expert way they do journals and books. With prior roles at SAGE Publishing, GVPi and Random House, Violaine has 18 years of experience in academic and trade publishing, including 8 years working with video publishing solutions.

Video is everywhere these days.

It’s on YouTube of course. And TikTok. Twitch. Instagram. Twitter. LinkedIn. Netflix. Prime. Hulu. Vimeo.

And, Zoom. So much Zoom.

But, you know where video isn’t? On academic publishing platforms. There are exceptions, of course. A handful of established “video publishers” with large operations: JoVE for research methods; Alexander Street Press, Infobase, SAGE Publishing for educational collections. Kanopy and Swank, while more generalist, do sell academic content to libraries. Select societies do, too, mostly in the medical sector, where video can helpfully be tied to CME credits. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons has made video a central part of its content strategy with its Orthopaedic Video Theater. The American Psychological Association has long offered PsycTherapy, a large collection of demonstration videos. ASCO has been leading the way with its Meeting Library. On the engineering side, SPIE has pioneered video integration into its Digital Library (see my interview with Patrick Franzen, their Director, Publications and Platform, in a video titled How to generate income from video proceedings). And, of course, most scholarly societies are embracing some form of video for marketing or learning purposes.

However, when it comes to publishing video products, there really isn’t much available out there. Let’s explore – and rebut – some of the commonly stated reasons why scholarly communications has missed the boat on streaming so far.

Reason #1: Academics aren’t interested in video

They just want articles and, maybe, proceedings. What we commonly hear: “Look, we’ve tried video abstracts, and they didn’t make that much of a difference, plus who is going to pay for them?” To which I would respond: Who was that video abstract made for? If it’s for academics, they probably aren’t interested indeed, because it takes longer for them to watch a three-minute video than it would to read the abstract itself. Like other forms of communication, video needs to serve a purpose, and it makes sense to use it when it adds relevance; whether that’s to demonstrate a method that needs to be reproducible, to present a technique that is better shown than described, or to tell a story that benefits from being heard directly in the author’s own voice.

Reason #2: Academic video is boring

That’s mostly true. What we also commonly hear: “But we put our session recordings online, and nobody watches them.” There are several very valid explanations for this. Academic videos are often long; they are poorly produced; they feature a LOT of slides, with not enough authors speaking to them. But what if we made those videos more viewer-friendly? There is no inherent reason for video itself to be an unpopular medium amongst academics. Publishers need to do the same homework with video as with any other content type: identify a need and find an efficient way to fulfill it.

Reason #3: It’s really hard to find “serious” video

That’s also (very) true. Where do you go today to find trusted video content? If you start on Google, unsurprisingly, you invariably get YouTube, the video platform owned by Google at the top of the results. Academic video isn’t exactly favored by YouTube’s ad-driven algorithm, which craves short, viral, sensationalist content. It doesn’t look like Google Scholar, Web of Science, Scopus, or PubMed are particularly interested in expanding their coverage of video, although it is possible that the explosive growth in video presentations spurred by the move to online conferences may make this more appealing to them. Most publishing platforms still treat video as a second-class medium. In fact, I would argue that there is more content available than it initially appears: societies, in particular, often have a wealth of media resources coming from different parts of their organizations. But those resources are typically not made or incorporated into publishing products; and when they are, they are barely indexed and largely undiscoverable.

Reason #4: Video is hard

As in, hard to produce and distribute. That’s partially true. Yes, making a video comes with a set of specific challenges (files are big!) but, most often, it seems unattainable because societies do not have the right staff, expertise, or technology — until now. I don’t know any more than anyone else what a post-COVID world will look like, but I am fairly certain that the abrupt move to online events is going to leave a lot of organizations with mountains of free video content to publish, and a lot of vendors eager to help.

Reason #5: Video is expensive

That’s also true, especially if your goal is to create well-produced video content like JoVE or the American Psychological Association. But all the more reason, then, to make the most of the content that you do produce, including publishing it properly. It has been fascinating to witness academics get a crash course in recording themselves over the past few months, whether for online teaching or for online conference presentations. There has been a steep learning curve, but everyone is learning. Teaching will – hopefully, at least in part – go back to the classroom, but these newly acquired skills will remain, and the pool of available video “authors” is now orders of magnitude larger than it was pre-COVID.

None of these reasons — individually or collectively — is a good enough reason to refrain from embracing video. So, here’s a call to arms, in eight steps, for those of you who are considering moving into video publishing.

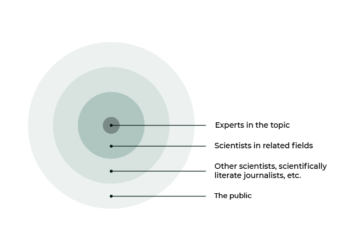

Step #1. Create your own market

We know that video is popular, especially amongst younger generations. Publishers have access to the best experts in their fields, including scholarly and professional societies that can tap into their membership. Give your experts ways to showcase their expertise. Investigate the new needs of higher education. Is there a reason why societies couldn’t play a key role in producing the learning materials needed for remote learning? The world hasn’t stopped needing the core function that societies provide, which is to bring experts together and facilitate communication amongst them and with the wider world. This doesn’t mean that the mission cannot be fulfilled in new ways. Journal subscription revenue is threatened, and cost-cutting is one way to address the problem, but how about increasing revenue by diversifying into video content?

Step #2. Make video more interesting

Give your authors better instructions. Buy them headsets – audio quality matters more than anything else. Have their recordings edited. Finding video experts is an easy task today: with just an iPad and zero training, even my 10-year-old can create the funniest videos (to the extent that video creation doesn’t count towards screen time at home – I enjoy the output too much). There is an entire generation of early graduates who are video whizzes, and the tools to create video have never been better and cheaper. Nobody expects this trend to stop.

Step #3. Don’t shun long-form video

If videos are too long, the answer isn’t necessarily to shorten them; perhaps the author does indeed have a lot to say. Just make it possible to skim it, search it, and skip to the part that matters. Watch times are always considered to be the best measure of success, but that assumption should seriously be challenged. If time is an academic’s most precious resource, isn’t what matters that they can quickly find and extract relevant information? If, for example, an academic finds a short segment they’re interested in, skips directly to it, watches the presenter for a minute or two, and clicks on a readily-available link to a corresponding article – can that reasonably be considered a user experience failure? Engagement can be overrated and is easily mistaken for what is, in fact, time wasted trying to find what matters most. While more and more resources are available, it has been shown that researchers tend to practice “strategic reading” (or, as Crossref’s Geoffrey Bilder would put it, “reading avoidance”). There is no reason to believe that “watching avoidance” would be any different.

Step #4. Treat video seriously

Make sure your videos are peer-reviewed. Give them a proper home online. Embed them alongside the rest of the research you publish: articles, books, proceedings, posters, presentations. Advocate for prestigious abstracting and indexing (A&I) services to index them. Have a business model for them, whether that’s charging a fee, making them open access, or monetizing them in other ways. Most importantly, market them — quote them, tweet about them, post extracts, write blogs and stories about them. The key to success for digital publishers has always been the right mix of quality content, clever marketing, and sound technology. Video publishing is no different.

Step #5. Tag and transcribe video

Scholarly publishers do metadata like no one else. Enrich your video with metadata, abstracts, DOIs, ISBNs, ORCID IDs, MARC records, captions, transcripts, translations. Streamline your workflows. Adapt your existing tools to incorporate video, or invest in new ones. Work on your metadata models like you do for books and journals. Be on the lookout for an upcoming NISO Recommended Practice for Video and Audio Metadata Guidelines (full disclosure, I am one of the co-chairs working on this) or, better yet, reach out to the group if you are already working on a model.

Step #6. Be creative

Video makes sense in most fields in some way, but what will work best? Methods? Techniques? A video review journal? Courses? Lectures? Can your new online events fuel year-round subscription products? Is there an opportunity for open access video? Video preprints, anyone? Once it’s online, video can be embedded and re-used more easily than any other type of content, which makes it an ideal candidate for trying out new products and business models.

Step #7. Make video accessible

Accessible players and platforms are rare but possible to find. Good captions may cost $2-$3 per minute of video, but they are indispensable. If you can’t afford them, enlist your authors to help, or perhaps your wider community who may be sensitive to the need to make content accessible to people with disabilities. Transcripts also make video more discoverable to search engines, easier to consume for anyone who isn’t a native speaker of the language used in the audio track, and effortless to understand when the speaker has a strong accent. And they save time for anyone who wants to scan the video and watch it at their own pace (I have made this argument at length in a Learned Publishing article, “Beyond the mandates: The far-reaching benefits of multimedia accessibility”).

Step #8. Think global

We’ve all witnessed how online events have broadened the reach of academic conferences overnight. Conferences are better documented than ever. Without travel requirements, and with recordings automatically available, conference content is now accessible by almost anybody, anywhere in the world, even long after the event has concluded. Societies suddenly have a whole new audience and an enormous amount of (virtually) free content with which to engage them.

It’s time for societies and publishers to do what they do best with video: publish it. Just not (only) on YouTube.

Discussion

9 Thoughts on "Guest Post — Video is here. Time to embrace it."

I feel like this whole article could be answered by looking at what Latest Thinking is doing for a couple of years now already:

https://lt.org/

Quite successfully if I may add.

Latest Thinking is great, just a particular kind of science video – of which I think there are many others kinds that could be developed further. The case is for all publishers and societies to embrace video in some form.

And let’s get some video KBART recommendations. 😇

Deal! Based on conversation we had at NISO Plus this year, our working group is supposed to feed into the new version of KBART.

Thank you very much for this important and necessary article arguing for videos in scholarly communication. For a couple of the described reasons and steps the TIB AV-Portal (https://av.tib.eu) is giving answers and opportunities in finding and publishing scholarly videos with advantages in long term preservation, citation features, deep indexing and much more. The Portal in 120 sec: https://av.tib.eu/media/22006. Give it a try. 😉

Hi Matti, thanks for mentioning the TIB AV-Portal, which would have deserved a mention in the post! Always admired its attention to enabling academic video discovery by applying publishing best practices to it.

Yes to all of this! Thanks for the nod, Violaine, as we passionately share your vision of creating and providing engaging scholarly video content. Infobase has been a staple in colleges and universities for over 75 years and in that time seen so many changes as to how content is delivered and used…and we love where the future is heading!

We are seeing more insightful, challenging, cutting-edge research being put into engaging videos and multimedia presentations. Creating concise and rich metadata and searchable segments has always been an important step in our process to ensure our media has all of the bells and whistles that instructors and professors expect in the year 2020. Resources like interactive transcripts, closed captioning, MARC records, segmented content or clips, enhanced metadata for searching ease, translations, on-demand delivery, interactivity, and the list keeps growing. This area of the educational market is such an exciting place to be and we can’t wait to see more of the amazing content that our publishers, producers, and colleagues produce and to share them with our academic market.

Anne Feldkamp

Director of K-12 Streaming

http://www.infobase.com

A few days ago I learned from a colleague at Springer Nature, Christoph Baumann, how he is approaching academic video, I put down some notes here: https://science-and-video.org/2020/10/26/systematic-approach-to-science-videos-for-academic-peers-and-professionals/ In the long run, Christoph says, videos shall neither replace lectures for students nor scientific books but will become an additional source for an easy information exchange between researchers and professionals in the private sector.

Use of video for peer-to-peer communication appears to be limited, however, since information exchange still works most efficiently via written text, in most cases.

With respect to video I’d appreciate any approach to standardize things: As long as each video requires huge individual efforts – well described by Violaine -, only enthusiasts will make use of it (and dedicate too much time to it). In the very long run, I believe, there will be standards for producing scholarly videos like there are standards today for publishing manuscripts in journals.

Hi Thilo, thank you very much for highlighting that blog post (and the Science and Video blog, generally). I agree that standardization is needed, but I am more optimistic than you are; NISO is currently working on a recommendation for standards and we are seeing more and more interest in the “publishing” of video content. Cadmore’s platform actually aims at making this process a lot easier with a streamlined workflow and the ability to automate repeatable steps, so video publishing isn’t only accessible to large publishers like Springer Nature.