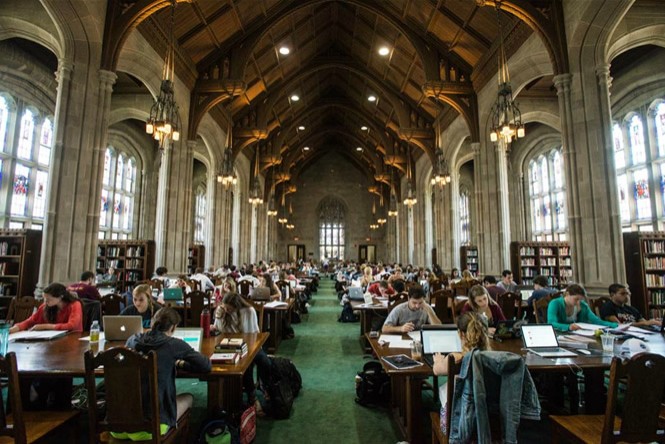

Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Emily Singley. Emily is Head of Library Systems at Boston College, and has previously held technology positions at Harvard University, Southern New Hampshire University, Curry College, and the University of Minnesota. She serves on the SeamlessAccess Outreach Committee, and her primary research interest is in how users access Library resources. (Full disclosure: Emily serves as a volunteer on the Communications Committee for SeamlessAccess).

On our highly residential campus, IP access works well. Or at least, it used to.

When the pandemic hit and all the students went home, we began to see e-resource usage decline. We suspect that our users, not understanding how off-campus library access works, simply gave up.

At Boston College, the majority of e-resource users navigate straight to publisher platforms, completely bypassing the library website’s proxied links. Like most academic libraries, we license resources based on campus IP range: if you’re on the campus network, you get through. Criticism of IP authentication is nothing new, and there is no lack of evidence of the user frustration it causes, but COVID-19 has sharpened the need to take action. At Boston College, we are turning to SAML-based federated access for a solution.

Why federated access? Because during the pandemic the one major vendor we’d set up that way — Elsevier — saw usage go up, not down. This came as a complete surprise: previously, almost all our Elsevier access had been coming through IP, with only a tiny percentage through federated. But once the students went off campus, federated access rose sharply. It seemed our now off-campus users understood federated access better than IP. We knew it was time for a change.

What is federated access?

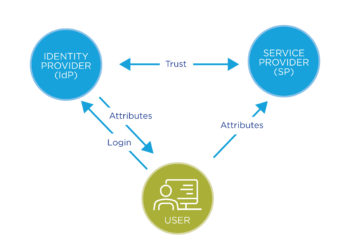

While a detailed explanation of SAML-based federated access is beyond the scope of this post (for that, I recommend SeamlessAccess.org’s short video as well as Aaron Tay’s excellent overview), here are three things you should know:

- Authorization is handled by the institution’s identity provider (IdP), meaning access is determined by a user’s actual institutional affiliation, not whether they are on the campus network.

- Many institutions who use SAML also leverage single sign on (SSO), allowing credentials to persist across campus services. This means that users who are already logged into common services like email, the learning management system, or even the library catalog won’t need to login again to access e-resources.

- Federated access underpins the SeamlessAccess service, meaning that for providers that adopt it, sign-on can persist across publisher platforms, allowing users to navigate seamlessly between databases.

Implementing federated access at Boston College

Spurred by the reality of a global pandemic, my library spent the summer implementing federated access. By mid-July, we had over 200 providers — including all major publishing platforms, university presses, aggregators, and individual journal titles accessible via federated connections. Now, as we begin the Fall term, we are better able to support both on-campus and online learners. Our implementation was not without some challenges, however, including:

Maintaining access for all resource providers

We do business with almost 600 e-resource providers, but only around 200, or one third, currently support federated access. So how to maintain access to all our resources, without having to run multiple authentication systems? We chose to use a hosted solution (OpenAthens) to manage all our federated and IP connections in one place. Similar solutions (e.g., LibLynx) are also available.

Working with IT

Federated access requires a SAML authentication infrastructure as well as membership in an identity federation — two things that are normally controlled by IT, not the library. At Boston College we were fortunate: our campus already had a SAML-based authentication infrastructure (Shibboleth) in place, and had already joined the InCommon identity federation.

But our central IT wasn’t staffed to set up and maintain hundreds of library resource connections. If we added over 200 new providers to Shibboleth, the library would represent a significant proportion of the total SAML connections on our campus. I found this surprising, but it probably shouldn’t have been — this is a tangible demonstration of how libraries really are at the center of the scholarly infrastructure. Luckily, because we were outsourcing the resource provider connections through OpenAthens (supported by EBSCO), our IT staff only needed to set up one Shibboleth connection.

Protecting user privacy

Before we could expand federated access to more resource providers, we knew we had to address privacy concerns. One good thing about IP authentication is that it preserves privacy: only the user’s institutional IP address (or, if the user is off-campus, the proxy server IP) is passed to the provider, thus limiting the ability to identify users individually. With federated access, it is possible to pass more information, including name, email address, and other identifiable attributes — Lisa Hinchliffe, as always, provides a good discussion of these pitfalls. But when federated access is implemented correctly, it is equally possible to preserve privacy.

We were able to preserve privacy — releasing only anonymous, non-identifiable attributes to resource providers — through close communication with the IT staff who manage our campus IdP. This is perhaps the trickiest thing about federated access: while the exchange of personal information is entirely controlled by your IdP (and that is good), librarians are often not consulted. Anecdotally, I’ve heard from e-resource providers that they see all sorts of scary personal information being inadvertently released by campus IdPs. As I’ve pointed out previously, implementing federated access requires librarians, as privacy advocates, to begin to build strong partnerships with their campus identity groups.

Looking ahead — getting to seamless access

Going forward, my library is prioritizing resource access that works regardless of whether users are on or off campus. Over the next several years, our selection process will be preferential toward federated providers, and we will be encouraging those who don’t yet have a federated option to consider one. I’m old enough to remember having similar conversations with providers back when we were trying to get them all to adopt EZProxy: now we need our providers to upgrade once again.

We will also encourage providers to adopt the SeamlessAccess service: on too many platforms, users still have difficulty figuring out how to use their institutional credentials. A consistent, recognizable user experience that persists across provider platforms will greatly improve the usefulness of federated access, and bring it closer to being a true replacement for IP authentication.

Why federated access matters — facilitating the scholarly conversation

By adopting federated access, my library has accepted the reality that, despite our best efforts to teach them otherwise, researchers don’t start at the library. Even before the pandemic, we saw evidence of users bypassing traditional library access pathways: in one study, we found students starting from all over the digital world — they tracked citation trails in online journals, clicked on links shared by friends, and followed threads on social media. They followed the scholarly conversation wherever it led them, dipping in and out of the library along the way.

Every morning, over my coffee, I engage in my own little scholarly conversation as I scan through article alerts on my phone. And I run into the same frustrations described in Michael Clarke’s step-by-step user journey: I have to figure out how to get to the articles by finding special library links that contains a magical prefix that re-writes URLs so that I look like I’m on an IP range that I’m not actually on. Isn’t that kind of insane, when you stop and think about it?

This same user journey gets much simpler with federated access:

- You get an article alert on your phone and click the link

- You’re able to sign into the publisher website with your institutional credentials (bonus if the publisher participates in SeamlessAccess)

- You read the article

Wouldn’t it be great if access could work this way for all library subscription resources? And isn’t it high time for libraries — and publishers — to begin to facilitate, rather than interrupt, the scholarly conversation?

At my library, it took a pandemic before we learned that IP authentication doesn’t really support the way our users want to work. And this year we made a small start toward improving the user experience by implementing federated access, if only for a fraction of our resources. There is more work to be done, but we can’t do it alone: it’s going to take all of us — libraries, publishers, and IT. Libraries need to be privacy advocates, publishers need to adopt federated access, and IT needs to collaborate with libraries. We still have a long way to go before we achieve truly seamless access, but by working together, I’m convinced we can get there.

Discussion

8 Thoughts on "Guest Post — Why Federated Access Matters: One Library’s Pandemic Story"

While I’m absolutely in favour of federated access, this comment interests me: “When the pandemic hit and all the students went home, we began to see e-resource usage decline. We suspect that our users, not understanding how off-campus library access works, simply gave up.”

Many publishers worldwide dropped paywalls in the early months of the pandemic to allow users the easiest possible access to content off-campus. The Microbiology Society, to take just one example, saw mean monthly full-text downloads double when the paywall was dropped. However, almost none of the usage could be attributed to a specific institution because users were not relying on library channels. How confident is Boston College that their users were giving up, versus getting access to the content because publishers had dropped paywalls?

Great comment, thanks. And yes, you are absolutely right, there are many reasons why usage may have dropped – not just the opening of paywalls, but also possibly, the fact that students may have been accessing resources less during the stressful early weeks of the pandemic. However, one reason we suspect that user experience was a factor was because we saw differences across different vendor platforms – for example, those platforms that are more likely to be accessed directly from the web saw starker declines than those that are more easily accessed from a library link.

I’m interested in your assertion “It seemed our now off-campus users understood federated access better than IP” I struggle to see what is so difficult to understand about IP authentication, can you explain this further? I agree with Tasha, Elsevier’s usage probably went up because pay walls came down, not necessarily because users used SAML more. We also know that during the pandemic, the likes of Sci-Hub crawled content at a huge rate, taking the same articles over and over again. How much of the increased access was full text downloads by researchers and how much was just crawlers and Sci-Hub. It would be very interesting to see the data. SAML is expensive and needs resources and, as you say, only 200 of your 600 resources support federated access, large libraries have more than 1000 resources so the percentage is even less. Globally, around 120,000 libraries enjoy IP address access, only a small percentage of them have a SAML based solution. As recent articles in the SK have stated, there is a lot of fear among libraries that publishers are pushing for federated access in order to facilitate the tracking of users and their behaviour. While I agree that federated access has a lot to offer it’s important to be aware that IP authenticated access will continue to be needed by a large number of libraries for the foreseeable future and publishers must be prepared to support this.

Thanks for the excellent comment, Andrew. I completely agree that IP authenticated access will be needed for a long time to come – that is why implementing OpenAthens was essential for us, because we needed to keep IP going. You also make a good point about the cost of federated – it is not something that libraries can do on their own: we were lucky in that it was already supported at our institution, but I realize that this is often not the case.

Emily, thanks for this very interesting and valuable post about your experiences implementing OpenAthens.

I’ve noticed something odd whenever federated access comes up lately — it is positioned as a replacement for IP authentication rather than for proxy servers, or this distinction is blurred. While to my knowledge all (or nearly all?) library proxy servers use IP authentication, not all IP authentication involves proxy servers, since most campuses provide direct IP-based access from campus. Proxy servers are designed to fill in the gaps when campus IP access is not an option, but federated authentication is being positioned as a replacement for both. What gets lost in the mix is that direct IP authentication from a campus network is broadly popular with everyone but security-minded publishers (and even they like it when it results in high usage and renewals).

It is appropriate to talk about federated authentication as an (eventual) replacement for proxies. It is much more of a stretch to suggest that they can replace IP authentication in toto. Has any campus, after implementing a federated system, contacted all of their vendors to have their campus IPs removed from their customer records? I would be very interested in a post from an institution that has made that leap. If none can be found, I’d be very interested in a post that examines what needs to be in place before that can realistically happen.

(By the way, I just want to note that it is just as easy if not easier for publishers to reroute users via that “magical [proxy] prefix” as it is to reroute users to their institutional IdP. It is just that most of them have chosen not to.)

Great point, Matthew. There is a need to distinguish between IP-based access and proxy server access – they are two different user experiences. At Boston College, we did not remove our IP range for federated vendors, because we didn’t want to significantly change the on-campus user experience. Until our campus has true “single sign on” we will continue to register our ranges. The good thing is that by implementing OpenAthens, this work is much easier to maintain and more streamlined. The bad thing is that users will still be confused as to why access works differently when they are in different places / on different devices.

A great post, thanks for taking the time to share your experience Emily. From a publishers perspective: even if a large part of our clients were to completely move over to federated access, we would still need to support IP based access for the rest. Compare this to the IP4 vs IP6 problem, we can never switch over to “The New Thing” while a significant need for “Clunky Old Thing” still exists. Also, the problem is not IP based access per se, but using a proxy service which causes hassles and confusion. One could envisage a remote IP based authentication without using a proxy service, but that would require significant out-of-the-box thinking.

Thanks, Etienne, and I completely agree that we will need the “Clunky Old Thing” for some time to come. And I understand your point about IP vs proxy service access, but would add that at least at my college, where most authentication is IP-based, not proxy server based, this access method is still problematic. I think we need to get to a point where access is not network based at all – because the rest of the web doesn’t work that way and our users do not expect it. Any access method that needs to be taught, is, I think, problematic.