The pandemic has wrought profound disruption on the academic sector. In the United States, impacts on face-to-face instruction and the residential model have resulted in substantial challenges to the student experience, while setbacks to scientific research and researchers themselves are no less significant. Increasing costs of retooling campuses and declining revenues from a variety of sources have caused significant anxiety and very real cutbacks. In early May here at The Scholarly Kitchen, one of us provided a primer for forecasting budgets in the US higher education sector, and subsequently we have dug deeply into institutional budgets for a number of commissioned projects. Today, we are able to share findings from a major research project about the budget situation in US academic libraries, from an out-of-cycle edition of the Ithaka S+R US Library Survey that we conducted this fall. Our results reflect the perspectives of 638 library directors — roughly 43% — from four-year colleges and universities in the United States.

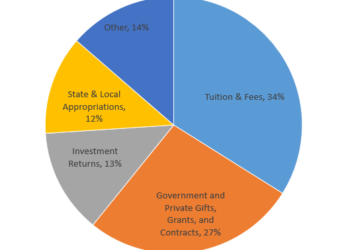

Across institutional types, higher education is seeing significant reductions in several principal revenue categories. The latest enrollment figures show an overall decline in first-year undergraduates of 13%, varying by institution type. And, given the greater financial aid needs for so many students and their families in this time of recession, institutions have had to offer higher tuition discount rates. These two factors indicate a decline in net tuition revenues across the sector. With state budgets under extraordinary fiscal pressure, direct appropriations to many public institutions will be reduced for years to come. Endowments nosedived in the spring, causing grave concerns, but public markets have rallied since, and many endowments ended the fiscal year up — and in any event, these funds cannot generally be used to address short-term emergencies. Universities administering hospitals and healthcare systems faced a substantial drop in revenue as routine care and elective surgeries were canceled or postponed. The scientific research enterprise has thus far faced essentially no cuts and even benefited in some cases from targeted stimulus, perhaps the most important bright spot at major research universities. Yet with most major revenue categories experiencing uncertainty and in several cases worrisome decline, and with few opportunities for new sources of revenue, budgeteers are making an array of spending cuts designed to stabilize finances and position their institutions for the future.

Academic library budgets

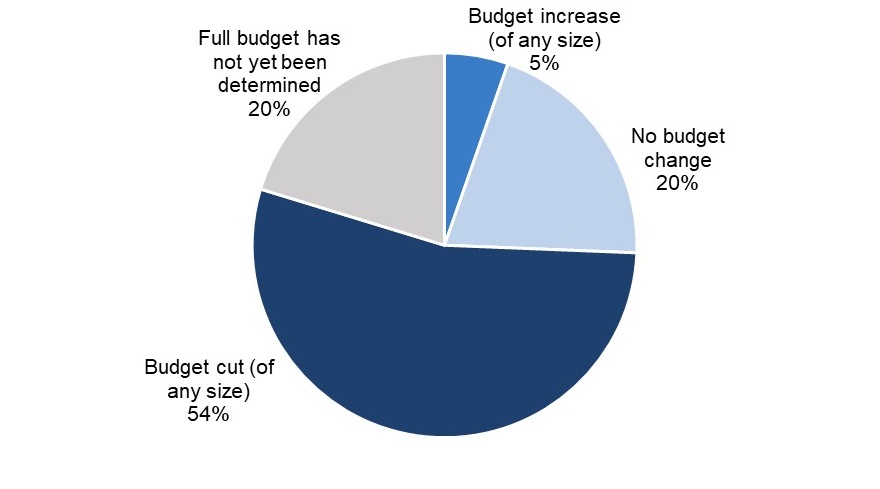

The overall impact on academic library budgets is still playing out, but it is already substantial. Of the directors who had their 2020-21 budget determined at the time of the survey, the majority — roughly 75% — have experienced cuts. Roughly 20% of directors reported that they did not yet have set budgets at the time that the survey was conducted in September. In these cases, there are indications that libraries have been subject to expenditure controls, pausing spending wherever possible.

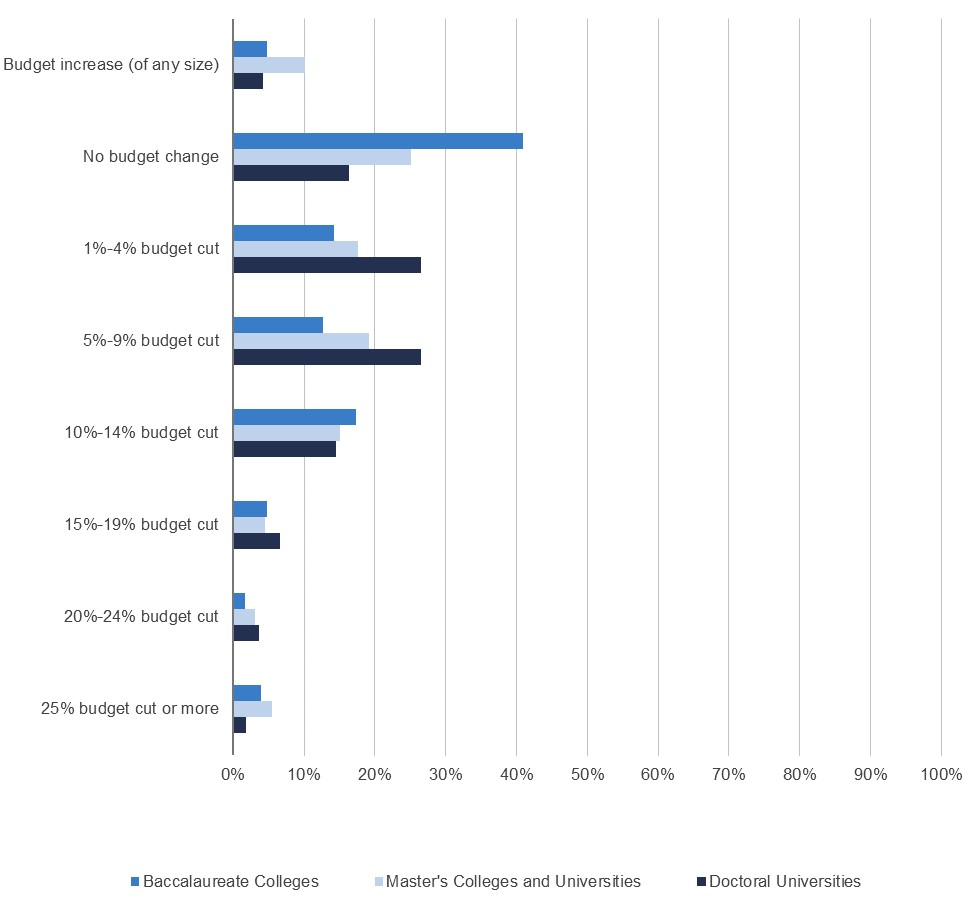

And not all institutions have targeted their libraries equally. On average, libraries at private institutions fared better than those at public institutions, and those at baccalaureate colleges were most likely to not report a change in their budgets.

How does the actual budget for the 2020-2021 fiscal year compare to what you would have otherwise expected before the COVID-19 pandemic? Please select the item below that currently best describes the percentage change.

Percentage of respondents that selected each item.

How does the actual budget for the 2020-2021 fiscal year compare to what you would have otherwise expected before the COVID-19 pandemic? Please select the item below that currently best describes the percentage change.

Percentage of respondents that selected each item, by Carnegie Classification. Excludes those who indicated that their 2020-2021 fiscal year budget had not been determined by the time of the survey.

When budget cuts have taken place, they generally spanned multiple expense areas, with a majority of directors across all institution types reporting some level of cut to collections, staffing, and/or operations. For each of these areas, a greater proportion of directors at doctoral universities decreased spending.

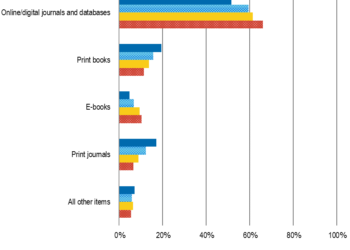

Collections spend

Libraries have steadily increased their investment in virtual services and digital resources over the past several decades. By 2010, library directors indicated that spending on online/digital journals and databases overwhelmingly made up the majority of their collections budgets. In the 2020 survey, directors reported that spending on e-books overtook print books for the first time. By 2025, library directors anticipate that spending on e-books will be nearly double that of print books. Streaming media is expected to be a more major area of investment — in fact, spending in this area is expected to rival that for print books five years into the future. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting shift to remote work has served to reinforce an existing acceleration toward digital resource acquisition.

In five years, what percentage of your library’s materials budget do you estimate will be spent on the following items? Percentages must add to 100 percent.

Percentage of respondents that selected each item.

Strategic directions

Given pre-pandemic investments in services and resources that serve scholars and students at a distance, academic libraries were relatively well-positioned to address relevant disruptions compared to some others on campus. Indeed, approximately seven in ten library directors agreed that their library’s previous digital presence was robust enough prior to the COVID-19 pandemic that they did not need to make many changes to strengthen it. They were just as likely to also agree that other senior leaders at their institution recognized this strength. For several survey cycles, we have reported on a decreasing sense among library leaders of perceived valuation, and this relative preparedness may have an impact in the long-term on the positioning of the library in the broader campus context.

At the same time, many higher education institutions implemented a variety of personnel and benefits reductions this year. Some three-quarters of doctoral library directors reported decreased spending on personnel, compared to about half of directors at baccalaureate and master’s institutions. Just as budget allocations are a more reliable indicator of strategic directions than are stated preferences, choices about how to distribute budget cuts and staffing reductions can provide clarity about strategic directions.

Across institution types, the most common approach to reducing staffing costs — reported by six in ten libraries — is instituting hiring freezes. Salary freezes and elimination of current vacancies were also fairly common, taking place at roughly four in ten libraries. These results appear to have minimized the impact of COVID-19 budget cuts on current employees.

There have also been furloughs and job cuts. While these are reported across essentially all library departments, they are unevenly distributed. Access services; technical services, metadata, and cataloging; and facilities/operations and security employees have been disproportionately impacted by this year’s budget cuts both through furloughs and elimination of both vacant and current positions. This makes sense: where physical library locations have closed, employees whose work is reliant on the physical space have been affected more. Still, even for these staff, elimination of current positions has taken place in an extreme minority of reporting institutions: only 6-7% of libraries that eliminated at least one position reported doing so with staff in these positions. Meanwhile, even as they are transitioning collections to digital and more likely to target staff reductions at those whose roles rely on the physical space, eight in ten library directors still see their physical locations as essential for carrying out their missions in the long-term.

Long-term outlook

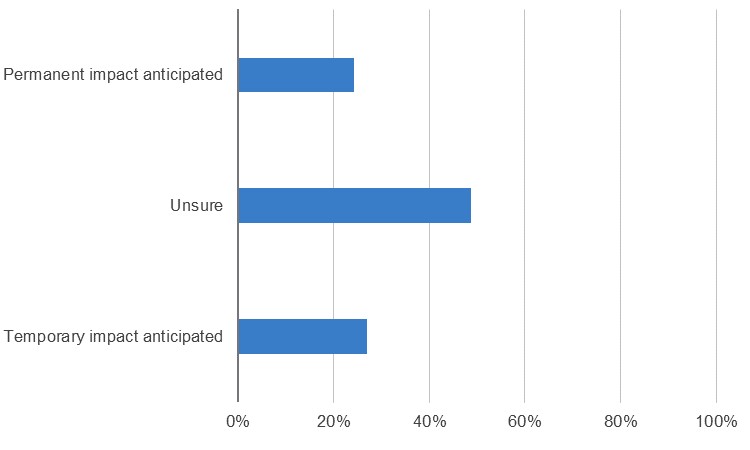

Library directors — like many other higher education leaders — simply do not know whether the budget cuts they have faced in the current fiscal year will be temporary or permanent. About one-quarter of respondents expect that COVID-19 will impact budgets temporarily and anticipate the budget recovering within a few years, while an additional one-quarter predict that cuts will be permanent. The remaining 50% fall in between these extremes demonstrating a lack of clarity regarding their budgetary future.

I anticipate that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on my library’s budget will be temporary (i.e. the budget will recover within a few years) rather than permanent.

Percentage of respondents that selected responses in each category.

Looking ahead

With so many US academic libraries facing cuts, some might be tempted to assume that the sector is bottoming out and will soon recover. To the contrary, we see risks of a further slide. In the current set of findings, nearly a quarter of responding directors report not having a budget for the current fiscal year: this often means that they are subject to expenditure controls and will spend less, in some cases far less, than they did in previous years. And while many directors are not sure what the future will bring, we have heard anecdotally from some that the cuts they are experiencing in the current fiscal year are part of a university effort to smooth anticipated reductions over two or more years, meaning that they anticipate further cuts next year. While a more optimistic scenario remains possible as the political and public health situations develop, it would be irresponsible to forecast that the sector has reached a nadir.

Like all higher education leaders today, library directors face the delicate balance of managing today’s challenges while also addressing long-term strategy. In light of present circumstances, publishers and other vendors have several opportunities to support the sector beyond the free access offers and price caps that have been extended. To take one example, in light of staffing austerity measures, there could be renewed attention to reducing the administrative burden faced by librarians to acquire, configure, and maintain products. And, with so many users working remotely, bringing greater seamlessness by reducing authorization, authentication, and other discovery to access barriers in an off-campus environment has never been more important. Libraries and publishers alike are only beginning to understand the impacts of reduced budgets, changes in work locations, and future higher education and funder priorities on strategies for achieving open access. And new product development may be more likely to target other budgets within the higher education sector than that of the university library.

All this remains to be seen. For now, we look forward to working with academic libraries, learned societies, scholarly publishers, and software providers to help navigate these challenging dynamics in support of the researchers, instructors, and students whose needs form the heart of the academy.