Editor’s Note: Today’s post is from Duleeka Knipe, Keith Hawton, Mark Sinyor, and Thomas Niederkrotenthaler of the International COVID-19 suicide prevention research collaboration (ICSPRC). Dr. Duleeka Knipe is suicide epidemiologist and a Vice Chancellor’s Elizabeth Blackwell Institute Research Fellow at University of Bristol. She is part of the Bristol Suicide and Self-harm group and is a commissioner and section lead on the Lancet Commission on suicide and self-harm. Professor Keith Hawton (CBE) is Director of the Centre for Suicide Research at Oxford University and Consultant Psychiatrist with Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust. Dr. Mark Sinyor is a psychiatrist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre and an Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Toronto. He is lead author of the Canadian Psychiatric Association guidelines for responsible reporting on suicide. Dr. Thomas Niederkrotenthaler is an internationally recognized expert in the area of media and suicide. He is research group lead for suicide prevention at the Medical University of Vienna (Austria) and current Vice-President of the International Association for Suicide Prevention (IASP).

Please be aware that this article talks about suicide.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the measures to address it have sparked considerable academic research about the potential impact on mental health. How this research is presented in the scientific literature and subsequently covered in mainstream media is of crucial importance. In particular, there is a longstanding challenge with responsible reporting of research related to suicide. Inappropriate reporting can contribute to further suicide deaths, whereas reports that may engender hope may prevent some suicide deaths.

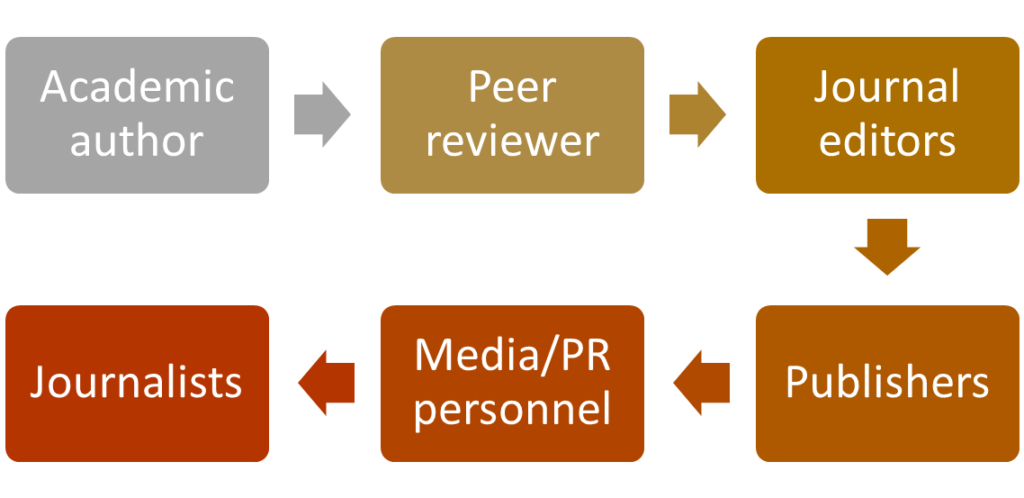

The obligation for responsible reporting does not weigh solely on the shoulders of journalists, as they often rely heavily on the content and style of academic publications and associated media releases to inform their reports. Everyone involved in the process of research communication bears responsibility. Whilst scientific papers themselves might primarily be written for an academic audience, in the era of open access publishing, direct engagement by the public and mainstream media has substantially increased.

There is strong research evidence documenting the harmful effect that inappropriate media reporting of suicide deaths can have on rates of suicide in the population. Concerning aspects of reporting include description of suicide methods, sensational headlines, and excessive reporting — these can lead to suicidal behavior among vulnerable people. Furthermore, associating the negative effects of the pandemic with suicidal behavior, unless done exceedingly carefully, carries substantial risk of normalising it as a way of coping at a time of crisis, which could inadvertently lead to more suicide deaths.

There is strong research evidence documenting the harmful effect that inappropriate media reporting of suicide deaths can have on rates of suicide in the population. Concerning aspects of reporting include description of suicide methods, sensational headlines, and excessive reporting — these can lead to suicidal behavior among vulnerable people. Furthermore, associating the negative effects of the pandemic with suicidal behavior, unless done exceedingly carefully, carries substantial risk of normalising it as a way of coping at a time of crisis, which could inadvertently lead to more suicide deaths.

Research also shows that disseminating stories of survival and resilience may be associated with lower suicide rates across the population. It is important to note that, regardless of how COVID-19 impacts suicide rates globally, it will remain true that the overwhelming majority of people who contemplate suicide will not go on to carry out suicidal acts. The suicide deaths that do occur should also be understood as preventable and those in the public who seriously consider suicide must be helped to recognize that these thoughts are a sign that they should reach out for help. Unfortunately, this crucial information is often omitted from media reports on suicide, both those regarding suicide research and in general.

At this challenging time, it is vitally important that the research community and those involved in disseminating findings do not contribute to increasing the risk of suicide in vulnerable populations. Media guidelines for the reporting of suicide have been developed and are now recommended by national (e.g., Samaritans in the UK) and international organizations (e.g., World Health Organization). Specific guidance during the COVID-19 pandemic also exists (IASP; Hawton et al (2020)). These guidelines typically target journalists and media professionals, but the principles apply to others. Titles and abstracts of research articles, as well as science communication efforts (e.g., press releases), often provide the basis for news reporting on research and it is essential that these texts are consistent with media recommendations.

We recommend that authors, peer-reviewers, university press offices, and journal editors consider the following points when publishing information about suicide during the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath:

- Remove references to methods of suicide from article titles (where possible) and avoid detailed description of methods (e.g., how a ligature was attached) in all science communication efforts.

- Descriptions of a novel method of suicide can contribute to spreading that method and should (where possible) be avoided. Where this is not possible, avoid referencing methods in the title and any detailed description of the exact method in the main text.

- Avoid simplistic explanations of suicide, for example single ‘triggers’ or causes of suicide (in this case, COVID-19 and its associated public health measures). Suicide usually results from a complex interplay of factors; it is rarely the case that a single event or factor leads someone to take their own life. We recommend that a statement about this complexity prefaces any speculation.

- Avoid sensational language, such as “surge”, “spike”, “crisis”, “tsunami”, and “epidemic” when describing the potential impact of the pandemic – these terms have been used out of context, generating sensational news headlines. There is currently no strong evidence of increases in suicide deaths during the first few months of the pandemic.

- Special care should be taken when describing suicidal behavior in young people, as this group is particularly susceptible to suicide contagion.

- Do remind people that suicide is preventable and in press releases and other marketing material highlight sources of help (e.g., list of international crisis centers). In these materials it is also advised that they should include stories of mastery of suicidal crises in people with whom the public are likely to identify.

These recommendations are not aimed at limiting discussion about suicide or to restrict publication of research findings. It is, however, essential that we all work together on safe and accurate translation of suicide research findings into media reporting that minimizes risks to vulnerable individuals and that might even confer some benefit to them.

Written on behalf of the International COVID-19 suicide prevention research collaboration (ICSPRC) — an international group of suicide prevention researchers and charity leaders from 39 countries. This group’s aim is to share knowledge to minimize the impact of the pandemic on suicide deaths globally.

If the issues in this article affect you, please see the International Association for Suicide Prevention (IASP) or contact an appropriate organization in your country.

Discussion

3 Thoughts on "Guest Post — Responsible Reporting of Suicide During COVID-19: The Role of Academic Publishing"

An added concern in this specific context is that one of the circulating conspiracy narratives is that the excess death statistics for 2020 are made up predominately of deaths by suicide due to public health measures and that these deaths have been attributed incorrectly to COVID-19 itself. Extremely clear discussion around where deaths by suicide fall in the context of the overall excess death statistics during the pandemic will be important to avoid inadvertently fueling that narrative.

Thank you for not using the terminology “committed a suicide.” As a suicide survivor – my older sister died by suicide five days before my 17th birthday – the stigma is enough and the added burden of likening suicide to an act of crime is unnecessary.

I lost my beloved adult son to suicide a few months after the pandemic was declared. While I think factors related to the pandemic were influential, I agree that suicide “usually results from a complex interplay of factors.” I applaud your work and your careful consideration of how elements of its reporting might influence one’s decision to attempt or complete suicide. However, I think elements in popular culture are far more influential–and that is my primary concern for survivors, including for my young granddaughter.