Author’s Note: I wrote this post 8 years ago, but have been thinking about it lately, as more and more of the publishers I work with seem overwhelmed by events. What is the future of my organization, they ask, or indeed of any publisher of scholarly materials in the face of animosity from the library community and the overweening demands of funding agencies? It’s important to bear in mind that there is nothing new about an adverse trading environment; you win or lose a game depending on how you play it. I note that many of the figures cited in the post would have to be adjusted to make them align with today’s realities (e.g., the percentage of OA articles has risen sharply), but I stand by my argument. There is only one option for a publisher, and that is to pursue a strategy of growth.

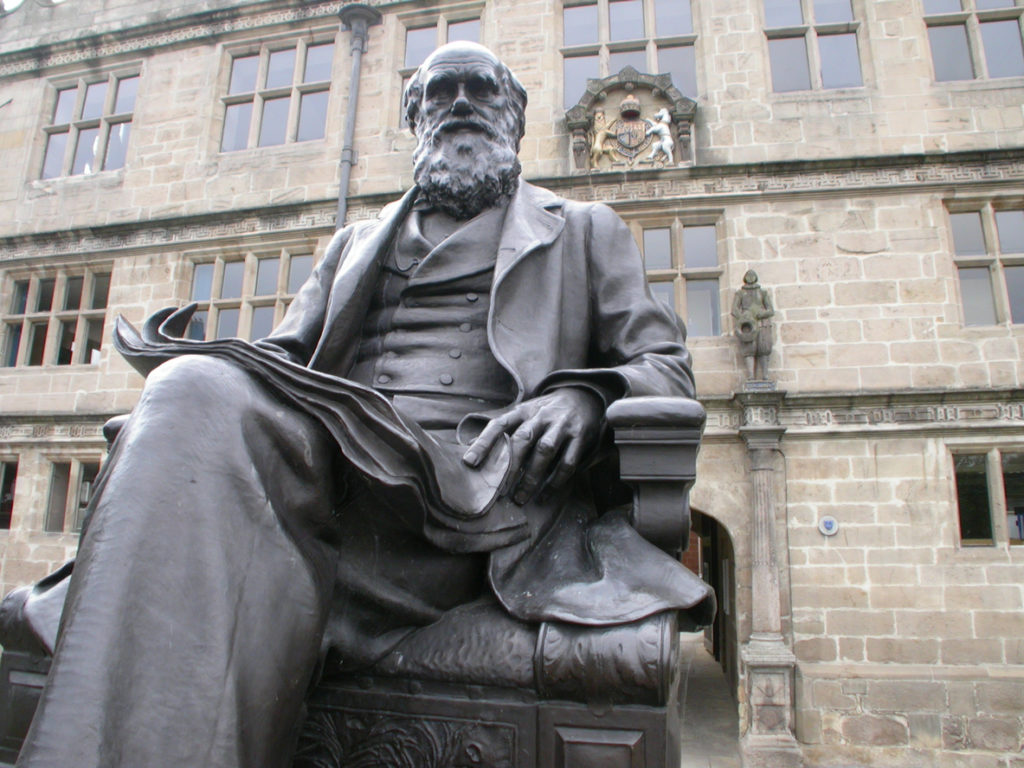

Open Access Millennialism is the belief that the world of scholarly publishing has a purpose and is moving toward the fulfillment of that purpose: at some point (but when? when?) all scholarly material will be open access (OA), and it is only the foot-dragging of self-interested publishers and the innate conservatism of academics that is holding it back. The signs are everywhere (“‘We would see a sign!’”): in the growing number of OA services, the mandates for OA from funders, and the general utility of locating content with no more than a Web browser and a mouse-click. I would have thought that the idea that history has a purpose was tossed out the window in 1859, but you can have OA without a sense of historical destiny. Just bide your time and let the utopians party. When you wake up the next morning, as I’ve said before, it’s just business.

We do have a number of divergent figures, however, that are likely to be reconciled in some way in the years ahead; these are in fact the two metrics that I personally keep an eye on. The first is that the average income to the publisher per article is about $5,000. You derive this number with great mathematical sophistication, by dividing the number of articles published each year (about 2 million) into the size of the journals market (about $10 billion). Voila! We now have a benchmark against we can measure OA pricing and services.

The reason that $5,000 figure (an average, I repeat) has captured my attention is that PLOS ONE charges $1,350 (Editor’s Note: now $1,749) and Peer J even less (though if you can figure out the Peer J business model from the public utterances, you will indeed have to engage in mathematical analysis far more complicated than long division) (Editor’s Note: PeerJ now offers a $1,395 APC). The $3,650 difference represents an imbalance that may, through entropy if not as a matter of destiny, force down the size of the journals market. This is the argument for subtractive change, about which more in a minute.

The other metric that I keep my eye on is another awkward relationship, the relative size of the OA market measured in dollars (about 2.3% of the total) and the number of articles available as OA, which is variously reported as in the range of 15-20%. (I believe the percentage is much higher, but much of Green OA is hidden in institutional repositories that do not see the light of day or the tender mercies of SEO.) (Editor’s Note: 2020 estimates are that OA has grown to 36% of the market in terms of articles, and just under 9% in terms of revenue) This is another argument for the subtractive scenario: the number of scholarly articles continues to grow (by 3-4% a year) as does the proportion of those articles that are OA, but the money received for these articles is much less than that for traditionally organized publications. Suppose the entire journals market, measured in dollars, were only 3-4% of what it is today? Or even 30%? What then? What would happen to the established publishers as they tried to rethink their cost structure to align with the emerging market realities?

A digression, if I may, into the world of books, where I keep my eyes peeled for trends in library circulation. It’s often said that 40% of books in libraries never circulate, a figure that, at best, is imprecise, but it points to another gap, that between the books in a library’s collection and the actual demand generated by patrons. Many libraries are seeking to align collections with patron demand, which can’t be good news for book publishers. What we see here are publishers benefiting from inefficiencies in the publishing ecosystem, whether for book circulation or OA growth and pricing. And here is the subtractive argument once again: as the inefficiencies are worked out of the system, the total cost of scholarly communications will drop.

So the subtractive scenario is that the total market will eventually shrink because of the economic disruption brought about by OA. The additive scenario argues that the market will be bigger, that is, revenue from OA will be additive to the revenue from traditional journals. And the substitutive scenario has the market remaining at essentially what it is today, adjusted for inflation, but with the mix skewing toward OA.

I made the case for the additive scenario in 2004, and I was right: the market is significantly bigger today. But how about ten years from now? And after ten more years have elapsed, will we still be asking what will be happening in ten more? This begins to sound like the Peak Oil argument, which is utterly convincing, but it is wrong. Peak Oil is not a function of how much oil there is in the ground but of how much human imagination you can bring to that oil. The market for scholarly communications is likely to have similar characteristics. As OA grows (as I think it will), its downward pricing pressure will be more than offset by the overall increase in the amount of research and the ability of publishers to tease new value out of that research.

Peak Oil is not a function of how much oil there is in the ground but of how much human imagination you can bring to that oil.

Let’s test the proposition. A show of hands, please, among the librarians reading this. How many of you have gone to your provost to say that you want to reduce your materials budget by 30% because the widespread availability of OA makes your current level of expenditure unnecessary? How many expect to have this conversation in three years? In five? Yes, let’s now ask the big question: What about ten years, don’t you think OA will have made your traditional collections budget irrelevant by then?

The votes are in and we see that not only do librarians expect to spend more money in three, five, and ten years, but the possibility that anyone would even consider sharp cuts to library budgets is something of a heresy. Librarians, in other words, are in an unholy embrace with the publishers they despise. If one goes, the other goes with it, and thus they are likely to continue to support each other. This does not have to be a friendly relationship; it just has to be an economically persistent one.

The problem with the subtractionist argument is that it is essentially a case of vulgar economics. It assumes that there is a law of supply and demand, that markets are efficient, that lower costs drive purchases. But of course none of this is true in institutional markets. The academy works via an economics of reputation, and the participants in this economy naturally look out for their own interests. We should not look for a $5,000-per-article publisher to embrace $1,350 without a whimper, and we should not expect a librarian to cheerfully make a case for fewer staff, smaller budgets, and a tiny building. The market is additive because it is made up of people.

For a publisher, which position you take on this matter is significant. If you believe in substitution, then your strategy is to replace toll-access revenue with OA revenue. You assume that you don’t have to resize your organization (though a lower cost structure is always desirable) and you spend your time on transition plans. On the other hand, if you believe that the OA Millennialists are right, you take out an axe; you have to get that cost structure down to where you can make money in a much smaller market. You look for a leaner operation and you strive to replace people with machines wherever possible.

The additive camp, though, begins with a different premise. This camp has as its bedrock foundation the belief that people make the difference. While reducing costs is part of operating every business, for the additive party it is not the strategic priority. To put this differently, it’s not the CEO’s job; it’s something to be delegated to someone further down in the organization. For the additive party the emphasis is on the new: new products, new services, new markets. The company that has just cut 20% or more of its staff is at a disadvantage in this scenario. The machines that have replaced them are very good at the things they do, but thinking up new products is not among them.

Having won my bet in 2004 — ten years later and the market is much bigger — I could take my money off the table and go home, basking in self-satisfaction, but I am going to let the money ride. This is because the future belongs to the creative. Let’s check back in ten years. For some of us, our optimism may exceed our life span.

Discussion

8 Thoughts on "Revisiting — Additive, Substitutive, Subtractive: Strategic Scenarios for Publishers in an OA World"

This blog posting has aged like a good wine! It seems crystal clear that scholarly publishers can defend and grow their market by adopting a creative, “OAplus” strategy.

I have a question about the nature of the transition.

Using publicly available data, I recently analyzed the proportion of articles funded by APC (Gold plus Hybrid) for a mid-sized scholarly society:

2017: 43.5%

2018: 43.5%

2019: 47.4%

2020: 51.5%

2021: 58.6%

Knowing the size of the APC and publicly disclosed publishing revenue, it was possible to calculate the revenue contribution of each paywalled article:

2017: $3,374

2018: $3,886

2019: $4,152

2020: $4,497

2021: unavailable

The same dynamic implies that the profitability of the paywalled(subscription) articles increased from 36% to 52% over the period. How long can this continue? (I have no access to private data so these numbers may not be 100% accurate, but I think shows a trend).

Taking this transition to its logical (absurd) conclusion the last subscriber will pay approximately $5.67M for the privilege of accessing the final paywalled article for this scholarly society!

Will the transition remain continuous, or will there be discontinuous step changes? Will the librarian’s boss ever refuse budget increases if they are used to fund subscriptions?

I agree that there is no reason for scholarly publishers to panic. By being sanguine and clear-eyed they will find new ways to add value.

Richard

P.S. I’m just completing a Discussion Paper on OAplus – if anyone would like a copy I can be reached at richard@rescognito.com or richard.wynne@cactusglobal.com

Thank you, Richard, for this interesting and informative comment. One thing that I would add is that growth comes in many different forms. I am myself not keen on growth through price increases. I am most interested in growth that comes by creating new value. In the book world this is usually discussed as the distinction between units and dollars. Dollar growth comes from price increases, but unit growth means you hve to sell more copies.

Joe Esposito

Joe, I love a good polemic and this is great stuff! I would love to see this with updated numbers as I couldn’t help but jump from the article to look at current figures (which makes the piece harder to read), but still lots to chew on.

A couple comments:

1. Great to see “OA millennialism” coined bc that’s very much what it is.

2. The framing around subtractionist vs. additive/creative is really helpful. If you substitute the word “risk” for creative, I think you start to get into the head space of more conservative publishers and their fears around what’s next.

3. For better for worse, every publisher strategy has to be growth because… capitalism. We don’t make the game, we just play it.

There are responsible, fair, good faith ways to grow — especially when you add the context of creativity to the dynamic — and there are not great ways, but there’s no way around it.

My question to larger community: Assuming the creative/growth approach, how do we do pursue these strategies without replicating the cycles of exclusion and appropriation that were foundational to building this community in the first place?

Joe, you asked for a show of hands of librarians who have gone to their Provost and asked for less money because of more wide-spread access to OA content. We have not. But we HAVE talked with our Provost about how and on what we’re spending our existing funds. And for this particular fiscal year the Provost gave us LESS money that we needed to cover journal inflation, but then gave us $400K in reinvestment funding – money that will be spent specifically in support of OA publishing initiatives of various kinds. The first allocation from that $400K reinvestment fund is going to a scholarly society to bring us in line with their new publishing/support structure, which will better support our institutional authors who publish in that society’s venues and will result in an overall reduction in our spend across the entire university with that society. The _Library_ will spend more, but the overall university spend will decrease.

The result of the Provost not meeting our journal inflationary needs meant we needed to cut subscriptions this year, and we did – partly via cutting individual title subs and partly through reducing our spend with one of the largest commercial publishers, where our multi-year deal with that publisher was ending as of 12/21. Our multiyear deals with two of the other largest commercial publishers are ending soon as well, one at the end of 2022 and one at the end of 2023. We anticipate going through spending reductions with those publishers similar to what we did with the first, and reinvesting those savings in/with publishers or other initiatives that better reflect our library and institutional values. The one sentence description that is being used to describe these efforts is: “We will be increasing investments to create community-owned infrastructure and shared digital resources, which may require less spending on purchasing content from proprietary, closed, for-profit scholarly information providers.”

So we may not be spending less, but who is getting what we DO spend is changing, and with the support of our Provost. A resolution being introduced into our Faculty Senate, that extends and expounds upon the one-sentence statement above, will hopefully result in similar support from our faculty.

Thank you, Mel. I wish you great success with your program. I suspect, however, that the “community-owned infrastructure” you cite will end up costing more than commercial offerings. See https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2018/01/09/50692/.

Interesting piece, Joe.

For those who’d like to learn more about the trends behind the numbers Joe cites in paragraph four, follow the link above to our October 2021 Market Sizing Update, or check out the webinar version here: https://deltathink.com/news-views-webinar-market-sizing-2021/

Always happy to have a chat, as well.

Hi Joe. I believe that fees currently spent on journal publishing would be better reinvested to support internal processes that provide immediate, open access to research. For example, assigning DOIs to research submitted for Library deposit (in open institutional repositories) would be discoverable via Altmetrics.

The article is about making money, not about increasing costs.