Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Erich van Rijn. Erich is the Interim Director and Finance Director at the University of California Press.

The Charleston Library Conference happened once again in person, and with a very robust number of attendees. It was interesting to observe what has changed and what has stayed the same since the last time I attended the conference in 2017. One thing that’s changed for the better is that the statue of John Calhoun that conference attendees have typically marched by on their way to sessions at the Gaillard Center was removed from Francis Marion Square in 2020 during the pandemic. One of the things that has definitely stayed the same, and has been amplified to some degree, is a strong focus of the conference organizers on open access. This has been spurred along by the messy inevitability of open access (OA) in the journals business and the library’s ongoing and somewhat uncertain role in facilitating it. However, I’ve also noticed an uptick in interest in open access book publishing models, and what libraries can and can’t do to facilitate these models.

Is Luminos Working?

In 2015, my former boss and current Scholarly Kitchen Chef/PLOS CEO Alison Mudditt led a team at the University of California Press who launched our Luminos open access monograph publishing program. The program survives to this day largely unchanged. Briefly, the program starts with the assumption the baseline cost of publishing a monograph is roughly $15,000. In order to recover those costs, Luminos uses a cost-sharing model that involves direct contributions from the author’s institution, money from a library membership fund, direct subsidy from the Press, and sales of print copies of the book. The elevator pitch for the program was (and is) that these funds combined allow for the global digital distribution of an openly licensed edition of the monograph. When it was launched, the Luminos program was one of the very few initiatives that was really trying to tackle the whole issue of open access books. Since then, many others have now waded into the fray, including the TOME project, which was launched in 2017, and Luminos is far from the only initiative that allows for open access book publication.

At dinner one night in Charleston, another publisher leaned over to me and asked bluntly, “Is Luminos working?” My answer at the time was, yes. But this question forced me to reflect a bit more carefully about the economics of Luminos and of OA monograph publishing more generally and what the library’s role in facilitating open access for books can really be. Answering the question about Luminos’s success depends a lot on what the measures of success are and how publishers, particularly university presses, deal with the difficult problem of the relationship between the costs of open access and the revenue derived from sales, largely to individuals, of their lengthy backlist of previously published books. Looking at Luminos strictly as a financial proposition, I think the results are a mixed bag. However, looking at Luminos as a way to create a pathway to immediate, unembargoed open access for the monographs published in the program that enhances these books’ impact and usage, I think it’s hard not to argue that it has been a success.

A chief challenge of the business of open access book publishing for university presses, however, has been the tremendously high costs of publishing a book. These are well documented in the 2016 Ithaka S+R study on the costs of publishing monographs, which is still in my opinion a highly valid and very important study, although not everyone agrees with the conclusions. The $15,000 figure that Luminos has used since its launch in 2015 is on the very very low end of the spectrum that is documented in that report, and is likely not realistic. But while not dismissing the cost side of the equation, I think what a lot of folks are beginning to consider is the revenue side, which is how university presses actually recover their costs of operation since most of us receive a small amount of direct institutional support at best.

Revenue from the Library

Many of the open access books efforts at university presses have been creatively exploring how to generate enough revenue through OA monograph publishing that authors can publish without having to do any independent fundraising. Several that emerged and were featured at Charleston, which largely focus on the collective buying power of academic libraries are:

- TheMIT Press Direct to Open model;

- Central European Press’s Opening the Future;

- University of Michigan Press’s Fund to Mission.

Beyond these program-specific projects, a somewhat recent entrant is the so-called “Third Way” Project, which is under development. It is a multi-publisher initiative that involves a one-time payment to publishers that would de-risk an embargoed free-to-read model for the ebook. Those one-time payments would be enabled by library purchases of a collection of books that would be made free to read after a period of time, but would be available to participating libraries immediately. (In the interest of full disclosure, I should mention that I have played a role at various points in its initial conception.)

Something these initiatives that have emerged in recent years have in common is that they are less focused on making a better case for the cost of monograph publishing. We all know acquiring, developing, producing, and marketing monographs is expensive, so how are we going to make this work? All of these programs lean fairly heavily on participation from academic libraries to make them work in a way that allows books to be made open (or, at least free to read) with no author payment required. This is not a small feat, and although there may be quibbles with all of these approaches, I think all are to be lauded for tackling the important project of trying to figure out open access books.

Revenue Beyond the Library

However, part of the issue with a flip to OA publishing for books as opposed to journals is that university press book publishing programs recover their costs by cultivating a diversity of revenue streams, which include academic library sales, but also sales to consumer channels. In addition, many of those revenue streams involve the sale of older, previously published “backlist” titles. Most university presses receive only a small amount of institutional support, if any at all, so we are generally forced to operate in the market to generate revenue to recover our costs of operation. Unlike journals publishing, where proportionately more revenue comes from academic library spending, my experience is that consumer purchases of books account for a very large share of most university press’s revenues. This is a feature and a bug. As library expenditures on book acquisition have declined over the decades, the consumer market has picked up the slack for many presses, which has helped keep the lights on for them. But on the flipside, it makes financing the publication of a university press book a lot more risky because it is less dependent on a fairly predictable number of library sales.

Academic book publishers, and specifically university presses, are rightly concerned that if a shift to open access publishing diminishes the ongoing revenue streams from consumer channels by making older content freely available in digital formats, this might have deleterious effects on a university press’s long-term sustainability as a program. This issue was cited as a possible concern already in 2016 in the Ithaka S+R report. The authors wrote:

As publishers introduce OA titles to their lists, most, if not all, will still have print and perhaps even a premium or enhanced digital version for sale via consumer channels. What will the impact on revenue per title be as a result of this? While such sales for an OA title will likely decline, it may depend on the title and the formats offered.

So just to summarize, there are two facts that are often overlooked when we discuss how university presses generally recover the costs of publishing their frontlist of new titles and how they might finance open access for monographs:

- A very large portion of a university press’s sales are not to academic libraries. Libraries are key to a university press’s overall success, and our model doesn’t work without them, but our model also depends on other revenue sources;

- Most of a university press’s annual revenues derive not from sales of new books, but from sales of previously published titles collectively known as the “backlist,” which are generally those titles that were published more than twelve months ago. The sales of these titles may adversely be impacted by the availability of open access formats as readers transition to digital.

Adding It All Up

I would argue that very few monographs recover their entire costs of publication within 1-3 years after publication, no matter what methodology you use to compute the costs. But the book economy that grew up in the post-WWII era allowed university presses to ride the long tail of their backlist into the consumer channels. Even monographs contribute to the backlist over time, often being adopted in college courses and selling in modest numbers annually that help a university press to recoup its investments in the newer books that it needs to publish. While sales of monographs have decreased over the years, I would argue that it has been many decades since academic library purchases funded the traditional university press’s operations single-handedly or nearly single-handedly even for the most specialized scholarship. Thus, the cost-sharing model of Luminos shines a light on the ongoing funding dynamic that will be necessary to continue to facilitate open access. Libraries can and should be part of that solution, but they can’t be the whole solution. One of the many successes of Luminos has been to ask the academic library community to contribute what I would call a reasonable amount to opening up monographs by contributing to a membership fund. Those who have stepped up have allowed us to keep the program operating as the program has grown to become nearly 20% of our monograph output. But I have concerns that even the Luminos model will create a drag on our backlist over time, particularly if it were scaled up without an increase in the funding that we receive per title.

The imprint of the traditional university press still holds value to many stakeholders in the scholarly publishing ecosystem. They are respected for many reasons, but first and foremost for the editorial development that they invest in a work. Our editorial teams, peer reviewers, and faculty committee members invest countless hours in projects, many of which go on to become field-defining projects, but some of which never even see the light of day for various reasons. That is expensive work. While I don’t think that it’s the libraries’ responsibility to fund a university press’s entire infrastructure, one or more stakeholders will need to in order to secure funding for a successful transformation of the monograph publishing ecosystem to a more open model.

So, is this a solvable problem? Yes, but we won’t get there overnight. Publishers usually want to make decisions that are informed by data. An NEH-funded study that the Association of University Presses is conducting with John Sherer at the University of North Carolina Press and myself as co-Principal Investigators on the continuing viability of sales of print copies in the consumer channels in an open access world will help inform the ongoing viability of models that continue to factor in some revenue from print sales. We have collected the preliminary data, and will be reporting our findings along with Roger Schonfeld and Laura Brown at Ithaka S+R in 2023. But as the world migrates seemingly inexorably to the digital, continuing sales of print books bankrolling the free availability of ebooks may be a transitional model, but likely not a transformational one. Other solutions will need to be found, and collaboration will be key. There is still work to be done to find a model that will really work for university presses.

But back to the original question from my publisher friend—is Luminos working? My answer would be that because it’s embedded in a 130 year old publishing program with a capacious and highly regarded backlist that can help bankroll it, we have been able to continue to make it work. It has created more equitable access to a lot of important scholarship, and it has made that work more impactful. But different publishers are still experimenting with different ways to tackle the thorny problem of generating enough revenue to programmatically support open access monographs. In 2015, we decided to throw caution to the wind, and worry less about how OA might impact the program. This was a bold move. We will continue to revise the model, learn what we can from other approaches, and continue to pursue other models that create a pathway to open access for our authors. Several other programs are growing and are standing on the shoulders of our effort and others’. They may yet build a better mousetrap. Everyone is still figuring this out — and we all should continue to do so while working collaboratively to crack this nut. From my perspective, no university press is going to solve this problem alone. There is still more work to be done, but I would argue that ongoing experimentation with different approaches to getting to open is in all of our interests in order to enhance the impact of university press scholarship.

Discussion

11 Thoughts on "Guest Post — Charleston 2022 — Finding Paths to Open Access Book Publishing"

As a mission-driven small, independent, family owned publisher, this is exactly the conversation we are having… we can (and will) fund some OA ourselves with our backlist – but the more success we have in opening our frontlist, the fewer backlist titles we’ll have to fund future publications. With no journals or associated institutions to directly fund us, I’ll be watching with interest while we also experiment in our own small ways!

Granted that we shouldn’t look at Luminos as a “strictly financial proposition,” it’s also true that unless the model is financially sustainable, it can’t continue doing all the other things that factor into its success as a project. Could you tell us a bit more about how Luminous is doing financially? Is it fiscally sustainable now, or on a firm trajectory towards fiscal sustainability?

A good question, Rick, and I’ll answer it as directly as possible. At its current output levels, Luminos is largely sustainable, and I’d like it be a sustainable option for more of our titles. There’s a lot more that I could say about the latter point that I’ll save for later. Part of the Luminos cost-sharing model was always a “UC Press Subsidy.” We’ve learned since we launched the program in 2015, that that subsidy has been somewhat larger than we originally envisioned, but we have always had strong support many key stakeholders in our mission to continue providing that subsidy through our other programmatic activities. That subsidy largely derives from other revenue streams like ongoing sales of our long backlist and outside fundraising. But the financial reality is that with a backlist of a 140 titles, Luminos would not be able to stand on its own two feet as a business entity and support all of its costs of operation without significant increases in per-title revenue or a *lot* more scale or both. Having said all that, the Press as a program subsidizes almost *all* of its monograph publishing to some degree, whether in Luminos or not, and Luminos provides a pathway to immediate open access with broad reuse licensed. It’s why a lot of authors choose to publish in the program.

Very helpful, Erich, thanks!

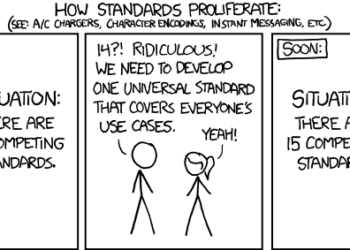

Thanks very much indeed to Erich for such a pleasingly reflective and un-messianic post on a topic perhaps not always awash with those virtues. It’s also great to be reminded of the historic importance of non-library revenue streams to monographic performance, and of the challenges posed by that key fact for OA modelling, in whatsoever guise. Which is why we continue to need all sorts of different experimental approaches: the idea of one, universalist solution to the OA monograph challenge seems now increasingly far-fetched. But that complexity will, of course, bring with it its own challenges, not least for institutions, and for funders…

I am disappointed to not see Lever Press (https://www.leverpress.org/) mentioned in your section on library supported OA efforts. Originally supported by liberal arts college libraries of the Oberlin Group it has grow to welcome support from any institution that values open access and Lever’s liberal arts ethos. Working closely with Michigan Publishing of the Michigan University Libraries (https://www.publishing.umich.edu/) and publishing open access ebooks on the Fulcrum platform (https://www.fulcrum.org/) it is opportunity for smaller colleges to play a part in developing OA scholarly monograph publishing.

Indeed, Lever Press is a great example of a born OA press that has a solid institutional commitment to making it work. This post was focused for the most part on a number of university press initiatives that were featured at this year’s Charleston conference. Many of these are trying to better integrate OA monograph publishing activities into their more traditional programs, and our mechanisms for supporting those activities differ from Lever’s. But we can also obviously learn much from Lever Press’s efforts and model.

One thing I would say is that the university presses making presentations at the Charleston Conference are in fact moving to the Lever Press model and other models that have been around for a while that have adopted consortial library funding & have been successful at that (including Knowledge Unlatched, Open Library of Humanities, Open Book Publishers, Annual Reviews, punctum books, etc.) — and it’s significant that Lever is a joint project between MPublishing, Amherst College Press and the library consortium, the Oberlin Group. I mention this because in my opinion the Lever Press initiative was probably one of the most innovative, low risk, cost efficient born OA presses we have seen in this country and the collaboration between 2 presses of differing sizes and catalogue emphases and a library consortium is unique and progressive. It is also worth noting however that since 2015, when the Lever group projected 90 titles by 2019, only about 18 titles have been published over a span of 7 years, and this means something is off but it is clear they are also on better footing now (I guess?) and maybe have even projected downwards the # of titles they want to publish each year: a good idea in my mind, although one would hope they could handle a scale of something like 20-25 titles per year: good for authors and good use of library revenue. My understanding, and Erich will correct me if I am wrong, was that Luminos launched with a somewhat similar but also different innovation and collaboration between UC Press, libraries, and universities all sharing the $15,000 cost equally, and it would also be interesting to hear exactly how that has worked out in terms of how the financial support has broken out per book over time.

I heard Alison Muddit give a talk on Luminos just before it launched at the University of California, Santa Barbara however many years ago, and at that time, I also read the working paper that provided the general outline for what became Luminos (which working paper was also the result of a research collaboration on the part of the press, librarians, and researchers: smart). My issue at the time was that, in the humanities and social sciences (primary emphases of UC Press), there simply is never $5,000 lying around in any researcher’s department or even in their research funds, provided by the university and/or external grants (typically, within UC system, e.g., early career faculty get such grants but no one else does unless they have an endowed chair or run a program, etc.). It just isn’t there and it still isn’t (the TOME pilot is a good example of a successful sourcing of not just library funds but also university administrative funds, such as from a provost’s office, but only so many, and not really many universities have the funds for this, so the model is deeply inequitable and maybe not sustainable over the long term?). When I shared with Alison that no humanities department I knew of would ever have the funds to pitch in 1/3 of the cost of a Luminos monograh, she said that was what Deans’ offices were for. I turned to the scholarly communications librarian I attended the event with and said, “has she actually hung out with Deans in the Humanities?” Full disclosure: I am a PhD in the humanities and worked within the university system from about 1993 to 2013 (and I am still an active scholar). I respect the hell out of Alison Muddit and everything she has done, especially with PLOS, but the humanities are not the sciences. So I’m simply curious about how the sourcing of funds from researchers has gone and whether or not Luminos depends more on library funding now than academic unit funding? & I’ve always been curious too about how UC Press sources the money from libraries: with what methods?

So I guess part of what I am trying to say here is that I don’t agree that new UP experiments with subscribe to open models for OA books is categorically different than what born OA presses have been doing for a while now, including Lever. So when Erich writes, in response to the commentator above who was disappointed not to see Lever mentioned here, “Many of these [new UP OA book programs and their revenue models] are trying to better integrate OA monograph publishing activities into their more traditional programs, and our mechanisms for supporting those activities differ from Lever’s.” I think that might well be true for Luminos and was actually hoping for more concrete financial information here relative to the question posed to Erich, “Is Luminos working?” Because the model is not like any other model I know of, and as someone who runs a consortial library funding program for OA books, I want to know more details re: how the $$ comes in, from whom/where, and where it goes, and what’s left over still to fund each book (on average) by the press? More pointedly for me is to say, yes, Lever actually *is* like the newer initiatives, period, because it adopts a collective consortial library funding model and these newer initiatives (Opening the Future, MIT’s Direct2Open, Michigan’s Fund to Mission, CUP’s Flip to Open, etc.) *all* have adopted a Subscribe to Open-styled consortial library funding model. I don’t know exactly what the cost point is for each book that is published open within each of these programs, and how that breaks out between what libraries supply and what the presses have to recover by other means, but I think that should be more transparent, especially for librarians. But following Erich’s thought here, maybe newer UP OA book initiatives will always be imbricated with their existing (and often heavy) costing models and therefore UPs will always have to recover costs by other means above and beyond whatever they source from libraries, even with these newer models. One day I will faint if I ever hear one UP say they are going to innovate their book costs, as opposed to saying they are always set in stone. Tthe director of Indiana University Press, Gary Dunham, is an exemplary exception. I met him during OA Week and was so impressed with what *he* has done around producing OA books. Story for another day.

But again, are these new OA book programs really different from Lever? In their original business plan Lever estimated costs per book at about $17,000 but again, I would love to know what portion of that was projected to come from libraries and what portion was to be covered by Lever (via MPublishing and Amherst College Press), or, was the idea that the $17,000 really would cover total costs of production? If the latter, I say: huzzah (although again: where are the books?). John Sherer made very transparent at the Charleston Conference (admirably, I might add), relative to the new “Third Way” program, that the cost point for each OA book would be $5,000 and that they are hoping for a commitment from libraries worldwide of about $2M annually for a total of 400 titles published each year: an innovative way to more rapidly scale up OA book production and on behalf of multiple UPs that might not be able to run library funding programs on their own: more equitable (for authors but also for presses), and more sharing of the burden of risk. It gave me pause though when Sherer said there would be a 3-year embargo on the titles, but again, as this is a highly creative project (I was just pleased to hear about a truly collaborative OA book program like this that will benefit many presses and authors), Sherer explained that the 3-year embargo is to help UPs recover their costs by other means, such as through digital book sales, because the cost point of $5,000 is low (!) and maybe that will scare UPs off, especially since the TOME project began with the cost point of $15,000 and according to the report on the 5-year project, that wasn’t enough for the majority of UPs that participated. What then does the TOME experiment lead to? Precisely to Fund to Mission, Direct2Open, Opening the Future, the Third Way, etc., regardless of which UPs participated in the TOME pilot or not. Not to mention you see the same business consultant(s) all over the landscape devising the “new” consortial library funding schemes for OA books. It’s the most “in club” I’ve ever seen. And the players are quite powerful compared to the smaller born OA initiatives who don’t have decades worth of inside library contacts nor “exclusive” benefits to incentivize libraries to participate, such as access to closed backlists or packages of backlist titles. And some presses with better university subsidies will always have a better ability to recover their costs, reasonable or not (cost inefficient at large scales, in other words). Never mind the smaller guys who innovated consortial library funding first (I place Lever in that category but with MPublishing and the Oberlin Group behind them, more turbo-charged, kind of like getting out of the gate on the fastest horse).

What is my conclusion here? Yes, Lever should have been mentioned along with a lot of other OA initiatives that have been around for a while. These projects did not spring, like Athena, from Zeus’s (traditional legacy) forehead. There may be different costing models for where money sourced from libraries goes, production-wise and/or operating costs-wise, and how different UPs recover revenue shortfall per book, but the funding model is the same: consortial library funding, sometimes with market-based incentives (that gives me pause too because all of a sudden, funding OA books got neoliberal and competitive) or not. Just once I’d like to see the boys club of UPs widen their circle, or get out of it.

Two components of the discussion that need to be laid bare (in the future reporting) are 1. granular detail into the reported costs of producing a monograph, and 2. granular detail on the impact of OA publishing on print sales. The former is taken as an article of faith – more or less – in the reported business costs of publishing from the relevant players and the latter is prone to hand wringing about the demise of print. Detailed and transparent data on both of these points will only serve to produce better publishing practices, strategies, and, ultimately, momentum in open access publishing.

So there’s no more granular information on the Luminos program?

Apologies if this has been mentioned elsewhere already, but what about the Steven King model? In retail publishing, it’s the revenue from a few bestsellers that makes it to possible to publish all the other titles stocking our local Barnes & Noble bookstores. Most titles sell only a few hundred copies each. Especially with today’s distribution and return models, it’s impossible for pubishers to cover editorial, design and production costs without subsidies—academic publishing is not alone in this. So, is the Steven King (or Ann Rice, JK Rowling, or John Grisham) model an option? Maybe it means developing a line of retail titles (or products) that subsidize everything else? Or maybe it means selling full freight to the public and using this revenue to give the books to students (or whatever target audience) for free? In other words, rather than treating open books as a weak product in need of constant support, can it be treated instead as a product made possible by an associated retail (and non-OA) component?