I recently hosted a webinar introducing some concepts around research impact — what it is, why it’s important, how it can be achieved and how it can be measured. I love these sessions because they draw people from all over the world and in exchange for sharing some of what I have learned, I get an update from the coalface on the challenges of fitting impact into your day-to-day life as a researcher, alongside everything else that is expected of you. I try to give a good chunk of the time over to questions because “what I think you should know about impact” is not always the same as “what actual researchers want to know about impact”. The questions always remind me that I may have dedicated my life to research impact and consequently see everything through that lens, but despite growing funder / governmental expectations around impact, for a lot of researchers, it is still uncharted territory. In a recent webinar one of the questions asked was “how related are journal impact and research impact?” This got me onto my usual spiel about the importance of separating academic impact from “real world” or broader impacts, and how they are essentially separate things. But, reflecting on the point made me wonder if they are not more intertwined than I have tended to allow for in my rhetoric.

Spiel part 1: journal impact is not inherited by the research published by that journal

Journal impact is usually a synonym for Impact Factors and other scores based on the average number of citations received by a particular journal in a particular period. Journal impact is not an indicator of the quality of individual studies published in that journal. The journal’s impact “score” is retrospective — it cannot tell you the influence that an individual piece of research will have in the future, even in academic terms. It cannot be taken as an indicator of the likely number of citations a paper will receive, and it cannot indicate what sort of change a study might lead to in the “real world”.

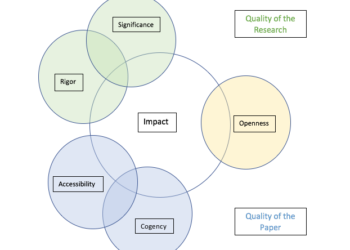

It is fair to say that a good journal Impact Factor does likely mean that more people try to publish in that journal (because it can look good on an academic CV, though many countries are moving away from evaluating researchers on where they have published). It then follows, to an extent, that the more people are submitting to a particular journal, the more selective it can be. And this, in theory, should mean that the research being accepted for publication by that journal is “better”. But note all the caveats I have used here. What constitutes “better” is still subjective, and depends on different editors’ and reviewers’ opinions. You cannot say that “research published in a high impact journal is in itself high impact”. That has to be established paper by paper, using a number of criteria, and will take years (I think the latest estimates are that it takes on average a year to get one citation, and maybe ten years for a paper to achieve the lion’s share of all the citations it will ever receive).

Spiel part 2: journal impact ≠ academic impact ≠ research impact

Even though a paper doesn’t inherit journal-level “impact”, that doesn’t mean its academic impact is not influenced by the journal in which it’s published. A more highly ranked journal might be more discoverable, and thus more widely read; more readership might lead to more citations. Possibly the journal brand might encourage a greater trust in the paper’s quality, or a greater exaggeration of the paper’s relevance, again broadening and increasing the citation potential. But the next part of my spiel makes the point that citation counts don’t equal academic impact, anyway, whether or not they’re influenced by journal impact.

Academic impact means the extent to which a piece of research has advanced knowledge in the field. This is not actually defined by citation count, however often citation counts are used as a proxy — it might equally well be defined in terms of the re-use of the methods or data published alongside the paper.

And however you’re defining academic impact, and whatever you’re using to try and quantify it, it is only one part of research impact — some would argue quite a small part.

Spiel part 3: research impact = real world impact

Research impact is made up of a much wider range of impacts with the lion’s share considered to be impact beyond academia. Indeed, the phrase “research impact” is defined by many in a way that specifically excludes academic impact — as “real change in the real world” (I’ve gathered a few definitions elsewhere). It breaks down into many different kinds of impact including changes in attitudes; awareness; economic or social status; policy, cultural or health outcomes (I like Mark Reed’s breakdown of types of impact). In the short term, such “broader impacts” can be quite independent from the academic impact, being achieved through dissemination and engagement directly with people like to benefit from or apply the research findings and recommendations. Broader research impact requires a purposeful approach to making sure that more people can find, understand and act upon your research.

But ultimately real-world impact potential is increased by academic and journal impact

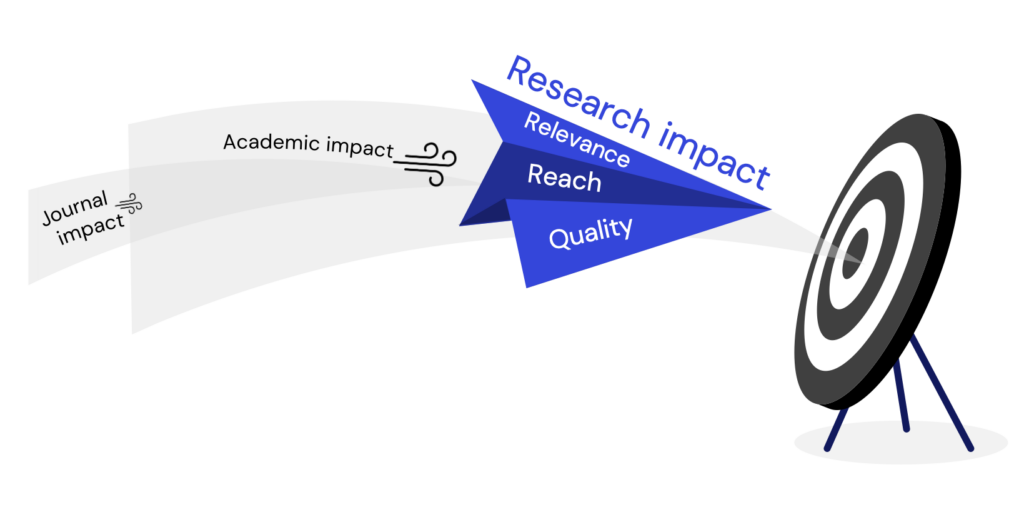

The conclusion I came to as I mused on this is that, for all this, journal impact and research impact are not as independent as I have tended to position them. The potential for broader impacts is arguably increased by the academic impact and even by the journal impact.

Broader / research impacts must derive from the relevance, reach and quality of the research itself. That is to say, they must improve something, solve something, change something (relevance); and the scale of this change is driven by quality (how well does the research solve the problem or bring about the change, and therefore how wide is the effect) – the latter also being a function of reach (how many people find it and understand it).

But each of relevance, reach, and quality can also be influenced by academic impact and journal impact. The more a piece of research advances knowledge in its field, the more follow up knowledge is generated — which in turn expands the scope and scale of broader impacts. So the academic impact increases the broader impacts. Meanwhile the higher the impact of the journal in which it is published, the greater the likelihood that the research will be found and read by those who can bring about that academic impact. So journal-level impact increases the likelihood of the academic impact of a specific paper, which in turn increases the broader impacts potential of the research the forms the basis of the paper.

Discussion

15 Thoughts on "How Related are Journal Impact and Research Impact?"

Most unfortunate that authors and researchers in the academia look for journal impact factor and never look for research impact. IF as has been said is not an indicator of quality of particular research that is published in that particular journal. Those in charge of publishing at universities push authors to publish their work in high IF journals without considering if the piece will have an impact on the practice, behaviour, industry, etc. in the community.

Absolutely. Some institutions are working towards recognising research impact, but the sector as a whole needs to acknowledge the importance of rewarding practical impacts, particularly when it comes to sustainability.

One question that was not answered here was how to assess research impact. There is a UK book on the matter, and what they did was to scan the grey literature, reports, media to see if research had been picked up outside academia, particularly in the research arena (this was a social science approach with an emphasis on public policy). So, if we had a routine scanning of the grey literature we could develop a RIF (research impact factor) which would, at the very least, be a proxy for uptake outside academia.

What’s the name of the book, please?

It’s nearly 10 years old, but one of the authors – Jane Tinkler – continues to write on aspects. It is Dunleavy et al with the title “The Impact of the Social Sciences”. See the link below.

https://methods.sagepub.com/book/the-impact-of-the-social-sciences

I’m a librarian whose career started back before PDFs, when journals were all in print and Interlibrary Loan meant bad photocopies and snail mail, or at best bad fax scans, and most research was still being done using print subject indexes, with a few indexes just starting to convert to CDROM, with their access limitations and poor search capability. And no one had heard of a Big Deal. Back in that world, there was absolutely no way to determine how many times an article was used/read, just cited. And it made sense to think that a more prestigious journal would be subscribed to by more libraries, hence its articles more discoverable which meant even more citations, etc. So judging an article/author by the overal journal impact factor made some sense and more importantly, was all we had (aside from direct citation counts).

But that’s not our world anymore. Now we can actually count exactly how many times an article is read, not just cited, and PDFs and digital transmission means that as long as the journal is indexed in one of hundreds of easily access “databases”, including big free ones like PubMed and Google Scholar, there is no reason any more to think that the prestigous journal is conferring greater discoverability to your article than a lesser one would, and thus greater “impact” on your field or the world.

But a lot of today’s top scholars did their training (aka PhD) under those older conditions and still think that the overall journal matters hugely to their own research impact. And sadly, a great many of those also serve on the Promotion & Tenure committees, and still apply those obsolete values to evaluating their younger colleagues’ research quality.

I am happy to work at a university where the main P&T cmtes don’t even look for impact factors in the applicant’s portfolio, although a few faculty do still provide them.

I might argue that we can measure how often an article is viewed or downloaded, but still have no clue as to how often it is “read”.

Which gets to the next part of your response — perhaps it’s less about “discoverability” than it is about “priority”. Every academic I know has a pile of unread PDFs on their laptop (or if they’re older, like me, a stack of printouts on their desk). What gets moved to the top of that pile and is more likely to be read requires a personal calculation, which certainly includes the reputation of the journal in which it was published. Note: journal brand reputation is not the same thing as impact factor, as every researcher has their own hierarchy and knows where the stuff that’s most relevant and important to them is published. The calculation probably also includes factors like who did the research (reputation of the research group and their institution).

I tend to think of all of this in the same way one looks at letters of recommendation for a candidate for a job or promotion. It’s all very qualitative and individual — what do I think about what the letter says and the person who wrote it? Unfortunately there is a bias for quantitative data (give me a numbered list I can look at quickly) and a quantity problem — if I have 1500 applicants for a job, I can’t carefully read all of their papers and I need a shortcut to winnow the list down to a reasonable amount. There are ways to do this beyond the impact factor, but often time pressures and laziness take precedence.

Good points. In the Release 5 of COUNTER usage data, which librarians use heavily for our licensed products, they distinguish “title investigations” from “title requests”, the former being any kind of measurable interest vs an actual full-text read/download “request”. I use “investigations” as an indicator of some interest in making recommendations for subscription additions/cancellations, eg. if 300 articles from a journal we don’t have a sub for have investigations, then I follow that title over to our ILL requests to see if the users bothered to take that next step or not.

This gets to the nub of the question – practicality. I have been involved – as many others have – with evaluating multiple research grant applications, multiple applications for promotion, and multiple applications for jobs. We are sometimes talking about dozens, but it can often be more than that. It is completely impractical to expect those doing the evaluation job to read these applications in details. Indeed, in the majority of instances these applications use quantitative data; they state the number of publications, whether or not they are in top journals, the number of citations, the previous track record of research etc. So, practicality, and a certain degree of objectivity, force us to use metrics of various kinds. If those metrics are faulty, then they need to be replaced with better ones. But they cannot be dispensed with. And of course in the end we exercise judgement, which can be subjective. So, our subjectivity is disciplined by the metrics, and that’s not a bad outcome!

I think “dozens” is a gross underestimate. A good friend is a department chair at a major public health school. When they advertise a job, they get hundreds, if not thousands of qualified applicants. But the scale point is essential to understanding why the much-derided impact factor hasn’t been discarded and replaced with something better. Most attempts to do so fail to understand two essential services provided by the impact factor (even if poorly provided):

1) Scale — If I need to take a stack of 1500 applications and narrow them down to a smaller, more manageable pile to look at in depth, a numbered ranking is an easy way to do that.

2) Very often researchers are tasked with doing something outside of their area of expertise. An outside opinion is often brought in on a hiring committee, or one’s research sometimes leads one down unexpected paths. Having a quick set of numbers to know which work in that field is important and what to read to get a handle on it is invaluable, rather than trying to read everything.

Neither of these problems can be solved by “just read the paper” approaches, as there’s not enough time in the day (or a lifetime) to fit all that in.

I’ve also made extensive arguments elsewhere about just how hard it is to accurately measure “real world” impact of research, particularly how the time scale of such research goes far beyond the typical grant/career lifecycle:

https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2018/08/02/societal-impact-meet-new-metric-old-metric/

Thank you for this post, Charlie! Could you elaborate on what you mean in your final sentence? “The publishing community needs to demonstrate that it is a following wind, not a headwind.”

Hi Cami, sorry for the tortuous analogy! Basically I am making the point that journal impact can act in support of other kinds of impact, rather than being a counter force. Publishers should feel able to make this point and use my arguments above to back up their claim to be supporting (rather than pushing against) efforts to achieve broader impacts. Albeit only in the way I outline above. Hope that helps?!

Thanks, Charlie! That does help, and I agree. Publishers are part of the research ecosystem, and we should all be working together (publishers, authors, institutions, funders, etc.) to help that ecosystem thrive. AND, to your point, publishers should get better about communicating how they SUPPORT community goals and initiatives where that support does exist.

Here is my definition of research impact:

Research Impact generally refers to the effect research has in areas outside the academia – economy, society, culture, Environment, etc.

The easiest definition of “research impact” is “Making the world better”.

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22705585.v1

Journal & Research Impact in my version.

Journal impact and research impact are related but not the same. Journal impact refers to the average number of citations that articles in a journal receive in a particular year. It is a measure of the reputation and visibility of the journal in the academic community.

Research impact, on the other hand, refers to the influence that a particular piece of research has on the field. It can be measured by the number of citations that a particular article or author receives, but it can also be evaluated by other metrics such as media coverage, policy influence, and patents. While journal impact can be a useful proxy for research impact, it is important to remember that not all highly cited articles are necessarily highly influential, and not all influential research is published in high-impact journals.