This posting represents an attempt to sort out the various ways in which particular characteristics of research and of written research reports interact with each other, and in particular the ways that those characteristics affect a paper’s impact on the real world.

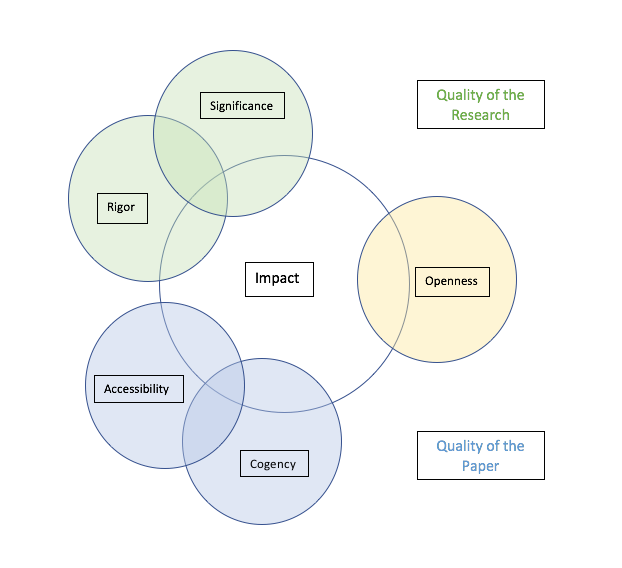

My conclusions are represented in this Euler diagram:

What follows is an explanation of the argument represented by the diagram—first, a quick list of provisional definitions for the terms used, and then a discussion of those terms’ implications in the context of the diagram.

Definitions

Rigor: the intrinsic scholarly or scientific soundness and intellectual honesty of the underlying research.

Impact: the effect, for good or ill, that a piece of scholarship actually has in the real world.

Significance: the article’s potential for impact.

Openness: the availability of the paper for reading and reuse.

Cogency: the rigor, accuracy, and clarity of the writing.

Accessibility*: the comprehensibility of the paper to the general reader.

Rigor

I’ve reviewed many scholarly papers, and when doing so I find that I’m invariably asked to answer questions like these:

- Is the research method scientifically or logically sound, and does it control for intervening or confounding variables?

- Was the data gathered rigorously and according to the method?

- Are the author’s arguments supported by the data?

- Does the author avoid making arguments not supported by the data?

- Does the author exaggerate the significance or strength of the findings?

- Is the article clearly and cogently written?

Unsurprisingly, most of these criteria map closely to the general rules of the scientific method: in other words, “rigor” questions tend to revolve around the issue of how well the research conforms to the rules of scientific inquiry.

Now, one might immediately respond, “Wait, but what about humanistic research?”. But in fact, humanists generally expect each other to adhere to the basic rules of scientific method as well: historians are expected to adduce evidence for their arguments about what happened in the past, not simply assert that events took place; scholars of literature expect each other to offer evidential support for their arguments about the influence of one writer on another, etc. The rules may not always apply in exactly the same ways from discipline to discipline, but the fundamentals are reasonably universal: whatever the discipline, scholarship requires evidence, honestly and rigorously gathered, and also requires that assertions take the form of conclusions that follow logically from such evidence.

Rigor has a bearing on both significance and impact because the more rigorous the research, the more likely it is to have resulted in valid findings — and valid findings are more likely to have genuine real-world implications than false ones.

Impact

The real-world impact of any piece of research will depend on many things: the number of disciplines for which it has implications (breadth); the significance of those implications for any particular discipline (depth); the effectiveness of its distribution within the population of those potentially affected by the findings, etc. This means that impact is, to a significant degree, a function of both the significance of the research and the openness of any reporting on it — and we can expect that both the accessibility and the cogency of the report’s content will affect its impact as well. Obviously, this isn’t to say that a relatively closed and/or inaccessible paper can’t have a significant impact: for example, if a cure for cancer were found and a resulting highly technical (thus, less accessible) paper were published in a very expensive toll-access (thus, less open) journal, we could expect that its impact in the world would be small — unless the privileged few who are able to read it are practicing oncologists, in which case the impact of the article would be felt by a great many people regardless of it being less open and less accessible.

But just because openness doesn’t determine impact doesn’t mean that there’s no connection between them. It’s obvious that a paper has more capacity to affect people and systems if it’s more broadly available, even if not everyone who has access to it is equipped to take full advantage of the content; if everything about the above cancer-journal scenario were the same except that the journal were open access (OA), there’s no rational reason for its openness to decrease the impact of the findings; if anything, it should increase the impact. (Could its openness have an irrational, or at least non-rational, negative effect on the paper’s impact? Yes — if, for example, the findings were dismissed by some oncologists simply because they were published in an OA journal. But in that scenario it’s ignorance, not openness, that lessens the paper’s impact — and even that effect would, I think, inevitably be short-lived. Eventually it would become clear that the cancer cure works. This effect could be more long-lived in other fields and disciplines, of course. And of course it’s also important to bear in mind that “impact” doesn’t necessarily mean “positive impact.” In the case of a paper that promotes dangerous and ineffective cancer “cure,” the more open it is the more negative its likely impact will be.)

What about the effect of quality on impact? In a perfect world, of course, the lower the quality of a piece of research, the less impact it would have. Unfortunately, our world is not perfect, and low-quality research regularly does have an impact in the world. Again, these are two characteristics that interact, though one may not strictly cause the other.

Significance

Since significance can be an ambiguous term, I’m giving it a provisional definition for the purposes of this model. That definition is “the article’s potential for creating impact.” The degree to which it realizes that potential will determine how much impact it actually has, obviously.

Is the content of an article more or less significant depending on how open it is? This depends on whether one considers significance a function of potential or actual real-world impact.

For example: suppose I discover a cure for cancer, but never tell anyone. Was my discovery significant? Arguably yes, on its intrinsic merits. If all that counts for significance is the potential impact and importance of the finding, then my article is equally significant whether it’s never published at all, or published in a toll-access journal read only by specialists, or made freely available in an online repository. However, if significance is measured by actual real-world impact, then my article will have no significance at all if I don’t share its findings with anyone else (and don’t use the information myself to cure anyone’s cancer).

The real — but not complete — overlap between significance and quality in this model suggests that there’s meaningful interaction between the validity of findings (as measured by the paper’s intrinsic scholarly quality) and the real-world implications of those findings (as measured by the paper’s intrinsic significance). In other words, a paper that reports the discovery of a cure for cancer is much less significant if the findings are fraudulent and the cure isn’t real. The false findings may create a large public reaction, and therefore appear to have significance, but this model doesn’t address “significance” in the public-relations sense, but rather in the intrinsic scholarly and scientific sense — according to which a finding is only significant if it’s real.

Openness

Openness — public availability of an article for reading and reuse — has some effect on the ability of an article to create impact, but doesn’t interact with any of the other variables. Why? Because a high-quality or high-significance article has the same intrinsic qualities regardless of the venue or manner of its publication. It may be published in the Lancet or in a fraudulent predatory journal; if it reports cogently on significant and rigorous research, its intrinsic qualities are the same. Similarly, an article will be equally accessible in the sense the term is used here (“easily comprehensible to the general reader”) and equally cogent (“rigorously and clearly written”) no matter where it’s published or under what copyright terms.

This is a really important point, because it goes against what seems to be an increasingly popular idea: that openness should be considered integral to quality. This attitude is reflected, for example, in the current policy at the University of Liège, under which publications will only be considered in a faculty member’s bid for tenure if they are deposited in the University’s institutional repository. Such policies make academic rigor and significance secondary to support for a particular mode of publishing and distribution. The logical conclusion of such a policy is that if a faculty member discovers a cure for cancer, publishes it in a toll-access journal, and fails to deposit it in the IR, her discovery of the cancer cure may not be considered when she applies for tenure. Obviously, this is absurd; it means that the researcher’s genuine scientific accomplishments and contributions matter less to the institution than the choices she makes about how and where to publish her work.

In this context it’s important to note that openness isn’t only a characteristic of written research reports, but also of research processes and practices themselves. Research conducted using electronic lab notebooks that make data publicly available in real time as it is produced is more open, for example. This is an example of the difference between open science and the more narrow concept of open access.

Cogency

Cogency has to do with the quality of the writing, and therefore applies only to the written report of a piece of research, not to the research itself. Here it’s important to note that quality of writing isn’t a frill — it’s not frosting on the cake of good science or scholarship. If the writing isn’t logical, coherent, and honest, that fact significantly undermines the value of the article. Cogency of writing has no effect on the intrinsic rigor and validity of the research itself, obviously; solid research is solid research, and the results are the results. Or, to put it another way: if you discover a cure for cancer and do a poor or dishonest job of writing up your findings, that doesn’t make the cure less effective. But misrepresenting the research — through either intellectual sloppiness or conscious deceit — imposes a damaging layer of obfuscation between the research results and the community that could benefit from knowing about and understanding them. Cogency shouldn’t be confused with accessibility, but the connection between them is obvious.

Accessibility

Bearing in mind that for our purposes accessibility means “comprehensibility to the average reader,” it’s obvious that cogency and accessibility interact both with each other and with impact: research that is widely understood has more of a chance to impact the world than research that is understood only by a few specialists — though, again, research that is understood only by a few specialists can still have very significant impacts on the world — and research that is cogently written up is more likely to have impact than that which is written up poorly or misleadingly (all other things being equal).

That said, though, it really is important to bear in mind that cogency and accessibility aren’t the same thing. As I argued in a previous posting, the cogent presentation of highly technical scholarly material may be unavoidably inaccessible to those who don’t have the foundational knowledge necessary to understand it — and since no one has the time to gain foundational knowledge of every discipline, there will always be articles that can’t be made easily comprehensible to every member of the general public without a meaningful loss of content or accuracy.

Another very important thing to bear in mind — and this basic fact is very often lost in the public discourse on openness in scholarly communication — is that we don’t, for the most part, live in a binary world. When it comes to openness, for example, it’s not generally true to characterize scholarship as either “closed” (“locked up,” “locked down”) or “open.” There exists a broad spectrum of openness and closedness, and virtually all articles fall somewhere between the poles of that spectrum. An article that is written but never published or otherwise distributed at all may be said to be completely closed. An article published in an expensive toll-access journal that allows no self-archiving is more closed than one published in a more affordable toll-access journal that allows its authors to self-archive without embargo. An article that is published in a free-to-read journal under a CC-BY-NC-ND license is more open than those, but is less open than one published under a CC BY license, etc. Ignoring the spectrum nature of openness and characterizing as “closed” every manifestation of publishing that is not fully open in every respect may be rhetorically stirring, but it gets in the way of advancing understanding of these important issues. (For a good discussion of this dynamic, see the Open Scholarship Initiative’s work on the “DARTS Framework” here.)

The same is true of all other characteristics discussed here. Accessibility, cogency, impact, significance—all of these are spectrum values, not binary ones.

And this brings up one final, but very important point: while we often use “impact” as a term with a very specific meaning in the context of scholarly communication, it is also a term the colloquial meaning of which matters very much. The significance of a paper for one person or group will be different than it is for another; the ways in which openness affects impact will vary from one publication to another. This diagram attempts to show areas in which the various properties of a publication interact with each other, but the nature of those interactions will be pretty variable from case to case.

* N.B. — There is another important dimension of “accessibility,” and that is the sense of “accessible to people with perceptual challenges of various kinds.” For our purposes, I’m including that sense of the term in the idea of “comprehensibility to the general reader.” For example, an article may be less comprehensible to an individual because it’s densely and technically written, or because the reader has dyslexia, or because the article is rendered in a font that is difficult for that person to see. In any of those cases, the result is that the document’s content is less accessible to that person (regardless of how openly available the document is). This means, among other things, that “accessibility” (unlike, say, rigor, openness, and maybe cogency) can never be a completely objective measure.

Discussion

8 Thoughts on "Quality Criteria in Scholarship and Science: Proposing a Visualization of Their Interactions"

Nice summary. A qualifying comment: The first four questions you mention in rigor cannot be answered effectively without openness of the data, materials, and research process. In that sense, open science might need to be connected with rigor. (Open access of the paper is not directly relevant for rigor, so I can understand why it was separated for that aspect of openness.)

There is another sense in which openness is relevant for rigor. It is much too easy to fool ourselves in the research process. An open research process, particularly pre-registration, can clarify the distinction between planned and unplanned analyses and mitigate inevitable confirmation and hindsight reasoning biases that undermine the rigor and credibility of the research claims. As such, open processes facilitate rigor for our present selves to remember the decisions of our past selves.

More info in this paper: https://www.pnas.org/content/115/11/2600

Thanks, Brian, good thoughts.

One point, though: rigor and the assessment of rigor aren’t the same thing. A research project is equally rigorous (in reality) regardless of how open the researchers are with their data and processes. You make an important point about the ability of (for example) trial registration to increase the likeliness of genuine rigor, but it’s important not to confuse openness with rigor itself. The conflation of those two concepts is a problem, I believe.

Rick interesting paper. But, I have to admit that I don’t see much of what you say. Science is tough stuff and most of the papers are not geared to the general public but rather to the cognoscenti. Science is a bunch of large fields broken down into discrete subsections. In fact, a scientist – at least those I have dealt with over the years – would not agree to read a paper and comment on it if it were not in their field. As an example of the rigor presented in science I give a list of some recent papers published by the Dr. Robert Harington’s math society:

Stably irrational hypersurfaces of small slopes

Stefan Schreieder.

J. Amer. Math. Soc.

Abstract, references and article information

Full-text PDF

Request permission to use this material Request Permissions

Classification of the maximal subalgebras of exceptional Lie algebras over fields of good characteristic

Alexander Premet and David I. Stewart.

J. Amer. Math. Soc.

Abstract, references and article information

Full-text PDF

Request permission to use this material Request Permissions

Regular supercuspidal representations

Tasho Kaletha.

J. Amer. Math. Soc.

Abstract, references and article information

Full-text PDF

I doubt if these papers fulfill your criteria – accessibility means “comprehensibility to the average reader,”

As for impact, the immediacy of impact is dubious, and if I can use an analogy, most scientific papers are bricks in a wall being built by the scientific community. Thus, few have immediate impact and some may have no impact whatsoever.

Perhaps this might be of interest too, https://zenodo.org/record/3366168 – in preparation for a larger study I did a literature study on the qualitative perceptions of scientific literature. The results are yet to be published – probably in German language.

Hi Rick,

Great article. I think putting together a framework at all surfaces the uncomfortable truth that we really don’t all have a shared definition of what good research actually is. There are an awful lot of hidden assumptions held by various stakeholders which to a certain extent underlies why as an industry, we find ourselves talking at crossed-purposes so very often.

I’m curious about your accessibility criterion. You mention how some research articles that can only be understood by a few people who have specialist knowledge are necessarily less accessible. If we think of accessibility as a component of quality, and by extension incentivize that, do we run the risk of reducing opportunities for researchers to do more complex and esoteric work?

I’ll admit to that being a bit of a loaded question. Back in 2008 when Osamu Shimomura was awarded a nobel prize along with Martin Chalfie and Roger Tsien for the discovery of GFP, he talked about the pressure that young researchers are under to do ‘easier’ research. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2008/shimomura/25936-interview-with-osamu-shimomura/

If we think of accessibility as a component of quality, and by extension incentivize that, do we run the risk of reducing opportunities for researchers to do more complex and esoteric work?

I think one should separate out “quality” from “impact”. You could do an incredibly high quality study showing the sky is blue that would have very little impact.

That said, I think the idea is that to be impactful, the research must reach the right audience where it will have that impact. There’s an argument to be made that the more openly available the work is, the more likely it is to reach that audience because you will not be excluding anyone on the basis of being able to subscribe to or purchase the article. But that’s probably only going to matter for certain pieces of research. Openness can potentially heighten impact but it does not automatically heighten impact unto itself.