One of the things we talk about a lot here in the Scholarly Kitchen, and in the various neighborhoods and niches of the scholarly-communication ecosystem generally, is public access to scholarly and scientific publications. We discuss the degree to which everyone ought to have access to those publications at no charge, and what are the most fair and effective means of making them freely accessible. We talk about the differences between “public access” and “open access.” We talk about the difference between technical accessibility and practical discoverability. And lately, it seems like there’s increased interest in another facet of access: comprehensibility of the content itself.

Let’s back up for a moment. It seems to me that there are multiple facets or dimensions of concern when it comes to public access to scholarly and scientific publications (which I’ll mostly save space by calling “scholarship” from here on). Actually, though, I wonder if it might be more useful to think in terms of layers:

Layer 1: Access to scholarship. This layer has to do with whether and to what degree the general public is able simply to find and to read scholarship. The easier it is to find and the less they have to pay to read it, the more access they have. Importantly, if you can’t actually gain access to the scholarship itself, then you don’t have either of the next two layers of access either.

Layer 2: Freedom to use content. This layer has to do with reuse rights. To the degree that scholarship is freely available to read, but not to reuse or repurpose, this layer of access is thin. This freedom grows and deepens with the reuse options made available to the reader. The most common ways of making reuse maximally free are by licensing the work to the public under a Creative Commons Attribution-only license, or by placing it into the public domain.

And then there’s a third layer, which is the one I want to discuss here:

Layer 3: Accessibility of content. Here the term “accessibility” doesn’t refer to the degree to which one may find, read, and reuse the scholarship; it refers to the degree to which the scholarly content itself can actually be understood by the generalist reader. And right now there’s some interesting debate going on about this layer of accessibility, with different voices making conflicting claims about the degree to which it’s possible (and desirable) to change the way scholarship is written and presented so that it will be more accessible to those who read it.

I won’t take the space here to rehash the various arguments, assertions, and proposals that are currently flying back and forth in discussion forums like the Open Scholarship Initiative listserv, in workshops put on by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, in fellowship programs designed to teach students how to engage the public with their research, on university campuses, and so forth. These arguments are mostly based on an important but too-often unexamined assumption: that scholarship can be made generally comprehensible to a lay audience without a sacrifice in meaning and content.

All of this begs two important questions: is it actually possible to make advanced scholarship comprehensible to the general public, and if so, is doing so a good idea?

Both of these questions are provocative and politically fraught. If you answer “no” to either or both of them, you open yourself up to accusations that range in seriousness from laziness or a lack of imagination (“Of course scholarship can be made intelligible to lay readers; it just takes more effort than scholars and scientists are willing to expend”) to the more serious ones of intellectual elitism (“So you’re saying the general public is too stupid to understand scholarship?”) or political reaction (“You just want to keep the people in the dark so they don’t rise up and change the system”).

Is it possible to make advanced scholarship comprehensible to the general public, and if so, is that a good idea?

It seems to me that reality — as it usually is — is a bit more complex than this, though. Let’s consider some of the reasons why a scholarly or scientific journal article might be difficult for a non-specialist reader to understand, noting that some are more legitimate than others:

- It might be poorly written – either unintentionally (such as by someone who simply isn’t a good writer, or who has a poor command of the language in which the article is written) or intentionally (such as in an academic jargon that tries to signal complexity, depth, or in-group status by obfuscation).

- It might be well-written, but using vocabulary that has specific disciplinary meanings that aren’t known to the general public (for example, think of the very different meanings that the term “alienation” has in psychology, Marxian economic theory, law, and theater).

- It might be presented in formats that make it inaccessible to those with disabilities of various kinds.

- It might describe concepts and processes that are irreducibly complex (such that simplifying them for generalist consumption would alter their meaning or obscure important nuances).

- In unusual cases, it might clearly and accurately represent work that is actually nonsensical and has no coherent meaning (as in recent sting operations designed to expose fraudulent publishing practices).

(I’m sure this list doesn’t exhaust the possible explanations for difficulty in a scholarly publication; if readers have others to suggest, please do so in the comments.)

People don’t usually make this comment publicly or explicitly, but I’ve heard some hint around that making scholarship more broadly and easily understood could actually serve society badly, because the general public doesn’t have the intelligence or wisdom to make responsible use of the information. What if we make all of the scientific literature on vaccination protocols both available to and easily understood by the public, and the result is more people being empowered to twist and misrepresent the data for anti-scientific purposes (whether intentionally or not)? For what it’s worth, I think this is an indefensible position; it applies equally well to any information whatsoever. If we’re going to have an intellectual (or, worse, ideological) means test by which we decide who gets access to information, our democracy is in trouble.

However, I would argue that the more difficult and interesting issue is not whether the general public has either enough native intelligence to understand scholarship or enough judgment and strength of character to use knowledge wisely; the more relevant issue is whether the general public has enough background knowledge to comprehend advanced scholarly publications. And the answer, obviously, is that sometimes they do and sometimes they don’t. And I want to suggest one important principle when it comes to making scholarship accessible to the generalist reader: apart from the writing style of the author, what makes a piece of scholarship comprehensible to the non-specialist reader may not be the complexity of the discipline itself, but the type of study being reported.

For example, oncology is a very complex field of scientific study. While one could certainly argue that anyone willing to put in lots of hard intellectual work would be capable of becoming an oncologist, it’s undeniable that the vast majority of people have not, in fact, put in that hard work, and therefore aren’t prepared at any given moment to start working as oncologists. But you don’t have to be an oncologist, or even have any background in oncology, to understand a clearly-written summary of the clinical trial of a cancer treatment. There is no reason why such a summary couldn’t be written in such a way as to make reasonably clear to a lay audience whether and to what degree the study indicated effectiveness in the treatment.

The degree to which it’s possible to make scholarship more accessible will vary by context and discipline, and the techniques that work will vary as well.

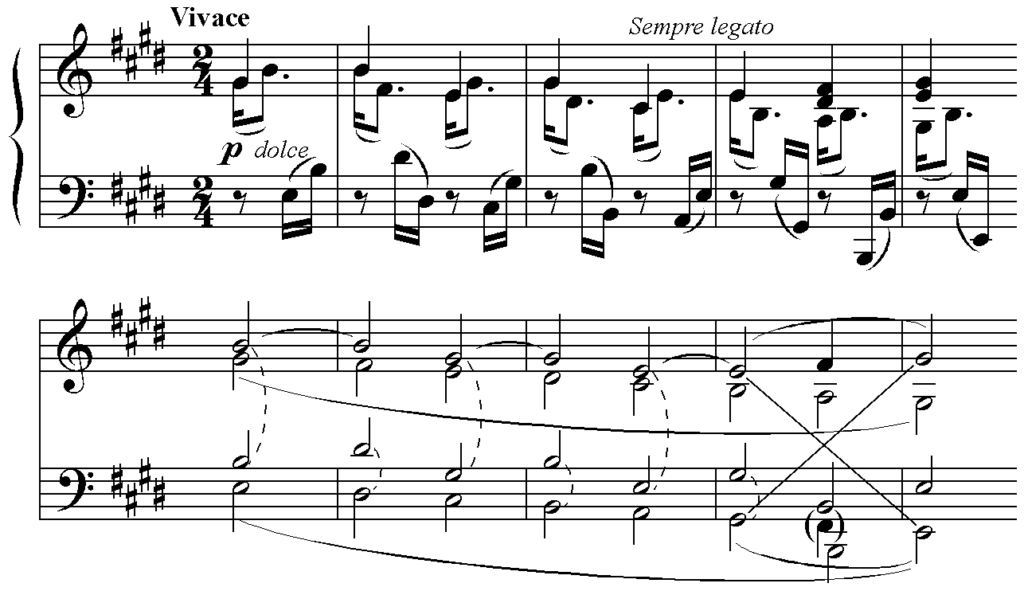

However, not all types of scholarly and scientific studies lend themselves to that kind of summary. To take an example from the humanities: Schenkerian analysis (a simple example of which is illustrated in the image at the beginning of this post) is an advanced form of musical analysis that is only comprehensible to someone who has a thorough grounding in music theory. There’s no way to “summarize” a piece of Schenkerian analysis and thereby make it understandable to someone who doesn’t know what a triadic inversion is or who doesn’t know the difference between harmonic modulation and harmonic mutation. Not all complexity can be reduced to simplicity without a real sacrifice of meaning. None of this is to say that the general public is too dumb to understand Schenkerian analysis; it’s only to point out that the general public consists mostly of people who have spent their time learning things other than music theory. The same issue applies to an awful lot of scholarly disciplines. Some consist of principles and concepts that could easily be expressed in more commonly-understood terms without undermining their meaning; others don’t. Clinical trial results are usually pretty easy to summarize in lay terms; mathematical proofs, maybe not so much.

What all of this suggests is that it may not be useful to talk about making scholarship or science “more accessible” in generic terms. The degree to which it’s possible to make scholarship more accessible is going to vary by context and discipline, and where it is possible, the techniques that work will vary as well. In some disciplines and with some kinds of studies, it may be wise to change the way in which studies are written up; in others, it may be wise to leave the writing alone, but add a layer of explanation or summary. And some kinds of studies may resist effective or accurate simplification at all.

Discussion

21 Thoughts on "Access vs. Accessibility in Scholarship and Science"

I spent a lifetime acquiring books and journals in the sciences. I understood from early on that I did not know what most of the people I was speaking with knew. Thus, I would start each interview by laying ground rules. They know the science and I know publishing.

Science is tough stuff and even if one reads summaries, etc, for the vast majority of us we will not understand what is presented and that is why we have scientists who if we want, after we have studied the topic and come up with some intelligent questions, will gladly spend the time answering our questions.

To quote: “Nobody understands quantum mechanics.”

Richard Feynman

Neither does anybody understand this Feynman’s oneliner. It would take a book to explain it.

Whether medical content is among the easiest to communicate is debatable. But it is true that the biomedical community (led by NIH) has made the largest investment among all the sciences in helping assure accesssibility and understanding by the general public. Public access policy, MedlinePlus, Clinical Trials.gov, etc. Maybe they just make it look easy! In a real sense our lives depend on it, as not every physician caring for a sick patient is well skilled and motivated to communicate effectively what we need to know and understand.

Whilst I agree with a lot of what you say Rick, I wonder if you’ve missed something. The difference between what something says (often in obscure language) and what it means in practical terms (often in more conventional language).

So to your examples. The oncologists (usually a team) writing their summary for patients will have written initially in deep statistical jargon that is impenetrable to those not versed in (or interested in learning, as you state it) the statistics vernacular. So what is written for oncologists is converted into what it means for policy makers or patients.

Likewise, Schenkerian analysis. The deep music theory jargon can surely be translated into what this means for the listener of the piece. How does that harmonic change alter my mood (the practical meaning) – regardless of whether I know or care if it’s a modulation or a mutation.

(Mutations and modulations are not totally unheard of concepts in oncology of course, but no doubt with their own specific meaning.)

Of course whether scholars should spend their time on practical relevance for every paper is a different question.

I think the argument misses the point of the scholarly article (or book). These are highly-evolved forms, with the purpose of generating a conversation among experts in a field. If every journal article had to be written for a lay audience, they’d all be 300 page long textbooks followed by the new discovery. This would be an incredibly inefficient way for experts to communicate.

So while yes, it is vitally important to communicate research results to the non-expert public, the journal article is not the right vehicle for doing so. This requires a different kind of communication, and one doesn’t need to lose one to gain the other.

I think part of the problem here is our tendency to discuss “the journal article” as if it were a single thing. A close reading of a piece of Emily Dickinson correspondence, and a mathematical proof, and a piece of highly technical musical analysis, and a description of a clinical study are all examples of scholarship or science, but beyond that they don’t have much in common. The fact that each of them may be published in a journal doesn’t somehow make them all examples of the same thing. As I said in the piece, there are some kinds of scholarship or science that can (and arguably should) be made more intelligible to the lay reader, or the implications of which can easily be summarized for a lay audience. My problem is with the idea that all of it can be, and therefore should be, and that if it isn’t intelligible to a lay audience it’s necessarily because the scholar or scientist is being lazy or elitist.

I think it’s also worth unpicking what we’re trying to achieve by broadening audiences for research, and whether “general public” is always the right way to describe those broader audiences. “General public” is too broad a term to be a target demographic, and represents an end of a spectrum that goes from “other people researching this specific thing” through “others in the general field” through “others in the discipline”, “others with a similar level of education” etc. If you focus too specifically on “general public” you create the challenge that David describes, of having to explain so much at so simple a level that it becomes impossible to create a meaningful / useful summary. But aim just a couple of notches further back on the spectrum and it becomes a lot easier to write a summary that will enable many more people to find and understand the research. For this reason, we’re careful at Kudos not to talk about “lay” summaries – as they aren’t necessarily for lay audiences. We talk about “plain language” which helps people both within and outside of the field. In the context of precision medicine, I recently (https://www.slideshare.net/growkudos/raising-awareness-of-and-engagement-with-precision-medicine/1) used the example of the general practitioner who now needs a better handle on research in molecular genetics and biochemistry. Forget the polarities of “arcane scientist vs general public” and focus on the grey areas in between!

That’s a great point, Charlie. We should probably think about accessibility or comprehensibility as a spectrum value: not “is this article accessible or not,” but rather “how far up the slope of comprehensibility would it be wise to push this article?”, where “wisdom” is determined by trying to figure out exactly whom your target audience is.

Of course, this won’t be satisfying to those who are arguing that everything has to be accessible to everyone and that if it isn’t, it’s because of laziness or venality on the part of the science community. I realize it sounds like I’m talking about a tiny lunatic fringe of advocates, but I’ve been surprised lately by how often I keep bumping into arguments like that.

I disagree with the attempt at division into cases that are more easy to think about here. I do not think that oncology is any easier to put in lay terms than Schenkerian analysis, nor is it necessarily more useful to do so. Schenkerian analysis is useful mostly to make statements about music intended for other Schenkerian analysts, but this is also the case for the statistical language employed when describing the outcome of a clinical trial.

I think a problem is that what what we need to communicate to other experts, is the result. What the non-expert needs to know is not the result, but what the result means. Now, my result means one thing to me and to my fellow experts, but this does not necessarily coincide with what it means to the public. Say that we try to see if some substance carries some increased chance of survival in some type of cancer. What we get out is some number for this, which we can communicate. This is, as you say, simple.

But then what? You need years of training to understand what that means. A statistically highly significant finding that your chances of survival improves with a factor of 3 does not necessarily imply that your chances are very good at all, they could be, for all practical purposes, just as bad as before, meaning that the result is pointless in the end where the interested public sits. But it can still be highly interesting for the experts looking for something to build on.

I think that it is fair to say that I should not hide this paper from the public. But would I do the world a service if I actively tried to maximize the impact of this finding with the general public? I’m not so sure.

Hi, Torbjörn —

Please note that I didn’t suggest that “oncology is any easier to put in lay terms than Schenkerian analysis.” I suggested that “you don’t have to be an oncologist, or even have any background in oncology, to understand a clearly-written summary of the clinical trial of a cancer treatment.” You’re right, of course, that a summary won’t communicate everything that a fellow oncologist would understand (or need to know, or be able to infer) from the study itself. The summary would serve a different purpose.

Rick,

Point taken, but that still leaves the question of what that purpose would be. This is of particular concern in a field like oncology, where over-broad outreach might actually make desperate people seek to go through painful experimental treatments that do them no good.

I think that the question of making research accessible is not one that should be solved within the context of single publications, but rather through a system of successively more accessible publication layers. But I’m not sure that is possible either.

Maybe we should start it easy: let’s make the Wikipedia articles comprehensible to an average reader.

While reading your text I thought that one of the reasons why research articles are hard to understand is that they build up on 5, 10, 20, 50 (or maybe more) years of research and the definitions tend to drop out in the process. For example, I’m working on some specific aspects of T cell activation, and of course I’d never explain in my paper what T cell activation actually is. One can argue that it is easy to find this background on Wikipedia, as it is already in the general knowledge. But T cells make a point here: the article on Wikipedia tries to summarize the whole knowledge we now think we have about T cells, in all the contexts and with all reasonable caveats. My personal experience when faced with a Wikipedia article that long (I sometimes search for some notion in physics or maths) is that after reading it I’m as dumb as before. Even if I understand the words. Even if I clicked on some of the links from the text (opening up on another long Wikipedia articles).

If even Wikipedia articles are tough, then I don’t see much hope for research articles…or maybe, to juggle the issue around: what should we do with the Wikipedia articles to make them really comprehensible to an average reader?

At a time when social media purveyors and participants are learning there are downsides to undiscriminating platforms, we should ask what that means for greater accessibility to scholarship.

You might ask whether scholarly journals truly are undiscriminating like Facebook and Twitter are. After all, we have peer review. But who gets to decide who a “peer” reviewer is? Or what a journal is? Maybe there are more nefarious purposes that a predetory publisher could pursue than vanity publishing. Could a nefarious state actor establish journals that publish controversial science with the explicit goal of magnifying disagreement around wedge issues like climate change, vaccinations and when life begins? What impact would that have on our politics? What if their goal was simply to disrupt the progress of science in the developed world?

I’ll argue that the value in our system of peer review and metrics is directly reliant on an audience that seeks to perpetuate it’s value. That is, a community of readers mostly composed of authors & reviews (or potential authors & reviewers). If we wanted scholarly communication to target the “general public”, we would need to engineer an evaluation system that wasn’t quite so ripe for disruption by intentionally bad actors. I’m not even sure that’s possible.

I don’t intend to suggest that the knowledge produced by scholarly communication should be restricted. But repurposing the journals system to target the general public seems like a move that could risk the very foundation of that system.

We should draw a distinction between understanding a piece of research (knowing what the authors concluded) and being able to evaluate it (judging whether the conclusions are reasonable). A fair portion of the population can do the former. However, it’s the latter that’s the more important and much rarer skill.

Perhaps pre-publication peer review should ensure that no paper is published with unjustified conclusions, so that readers get an honest assessment of the papers’ importance. In late 2017 that notion seems quaintly naïve.

The upshot is that we’ve made research more accessible (=understandable) than ever before, but very few readers heed the caveats and concerns of the experts who are able to actually evaluate it. The bullsh*t gets all the way round the world while the truth is getting its boots on.

Rick, thanks for another very thoughtful post. This point about accessibility is being felt awfully close to the bone lately, for sure in my own discipline of history but also of course in any field where expertise is being disregarded. A lot of historians are spending more time attempting to communicate to general audiences. A case in point is the confederate memorials debate, where historians point out that many of these memorials were erected relatively recently in the twentieth century, not in areas where the Civil War was fought or where Confederates had any specific historical legacy to memorialize, and thus the memorials themselves are about an entirely different legacy. Making this information accessible seems incredibly urgent right now. But the research in which this is based was largely –though not entirely–written for specialist audiences and put through peer review. In short, I think it’s not only the case that some subjects aren’t necessarily comprehensible to a non-specialist, but also that specialist literatures have a vitally important role in building syntheses which can and should be.

Not sure where to begin.

I am trained as a music theorist. I am not a particularly avid proponent of Schenkerian analysis — it’s rife with problems, including but hardly limited to a particularly 19th-century-specific teleological determinism as well as a near-theocratic prescriptive outlook — but it has its uses and the approach has some merit.

Nevertheless, scholarly research is by nature additive, in the sense that (as signaled by the emphasis on citation) a scholar’s work builds on what comes before, and before that &c. It is communication by and for specialists, and for good reason.

There is no reason to expect someone not versed in Schenkerian notation to be able to read it. Indeed, the commenter above who wants to know how the passage should “make him feel” (paraphrasing) has so completely missed the thrust of musical analysis as to make the task of trying to communicate the diagram utterly pointless.

Naturally, this sounds horrible; I apologize. But I am just as ill-equipped to understand the significance of an oncological breakthrough. And that’s fine. In fact, if my not understanding research articles about oncology is what it takes for cures for cancer to advance, I’m all for it. Why should my layman’s ignorance inhibit the progress of research? I can read the summary in the New York Times (or whatever) if it comes to that.

The unfolding of diminutions and progression of the Ursatz through the middleground of the Beethoven passage above has the same effect. If for whatever reason a theorist chooses to pursue this [outmoded] method of anaylsis — what is the supposed recourse? Should every article using Schenkerian analysis include a five-page boilerplate explaining the foundations of the theory? Seems like if someone cares that much they can go to the damn library and acquire the means to understand it.

(Perhaps I’m defensive; music theory is poorly understood in general and often (unfairly IMHO) held up as a needlessly esoteric discipline. “It’s music, it makes me feel blah blah blah.” Music is encoded culture; meaning is largely supplied by the listener; the analysis of music can teach us volumes about the cultural conditions under which it was created. Viz. the early triadic theorists of the 14th century and their fixation on the Trinity, or the 19th c. German obsession with organic growth vis-a-vis the Romantic preoccupation with “nature.” That it provokes an emotional response is not analysis — there are other fields of study that address this phenomenon. But I digress.)

So. There are plenty of accessible tracts on music — maybe not so much for oncology? But what is the utility of dumbing down oncological research so that I can understand it? I suggest that there is none.

Let us let research/scholarly articles be what they are. There are other media — “popular” science outlets, for example — to distill and communicate this information to the public.

Off topic: I am grateful that the commenting system interprets my double-hyphen as em-dashes.

Theoretical research in my discipline, economics is not going to be accessible to the “general public” much of it is not accessible to applied economists (including me)… On the other hand, most empirical studies and some applied theoretical studies could be given an executive summary to make them understandable to a broader audience. A few journals do this, but also bloggers, journalists etc have that role. The details of most scientific research need a lot of training in order to be able to understand them. But I also think it is true that most people aren’t intelligent enough to understand (mathematical and statistical) theory of this sort, i.e. training won’t work.

I spend more of my time thinking about undergraduate students than the general public but much of what has been said here applies. A very thoughtful essay Rick. Thank you. If I might, you might find this piece grappling with the role of scholarly articles and first-year students interesting: https://meredith.wolfwater.com/wordpress/2011/10/27/i-need-three-peer-reviewed-articles-or-the-freshman-research-paper/