Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by David Parker. David is the co-founder and Publisher of Lived Places Publishing. In previous professional roles, David founded Business Expert Press, which has more than 1,000 titles in its catalog today. He was also editor-in-chief at Pearson Education early in his career.

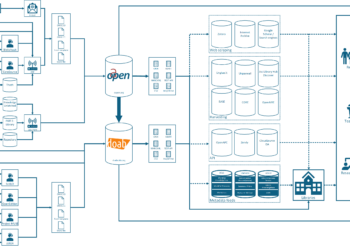

Funding open access ebooks has advanced significantly in recent years beyond book processing charges (BPC) levied on authors. Originators of alternative funding models, such as crowdfunding from Knowledge Unlatched, have spurred an increase in innovative models that rely on a mix of grant funding, central university funding, and library funding or converting books to open access upon the realization of a revenue target. Examples include Direct to Open (2DO) from MIT Press and Fund to Mission from University of Michigan Press, which rely on a mix of funding participants, most prominently library supported membership or subscription commitments. Cambridge Flip it Open and Bloomsbury Open Collections convert pre-selected books to open access upon realization of a pre-set sales target.

But these newer models for funding open access, as effective as they are in replacing BPCs, are vulnerable to a specific critique regarding institutional participation. From the perspective of global participation and support, these new models are likely out-of-reach for most institutions. If the base of institutions funding these open access models are in the hundreds rather than in the thousands, and based largely in Europe and North America and not in the Global South, we should ask if authors from these non-participating institutions will be equally pursued as publishing targets. I am not suggesting a willful disregard for authors from the Global South, but rather that editorial staffing, practices, author signings, etc., often reinforce past patterns without very intentional intervention. Time will tell and data will emerge as to who is being published and from which continent and institution they work, but the concern should keep us open to funding solutions that avoid BPCs and ensure global participation from libraries in the Global South.

The Troubling Logic Behind Book Processing Charges

The BPC is, in my view, deeply problematic. There are two reasons: 1) The burden to absorb the publishing cost often rests with the author, when it is not covered by university funding. And while it is true that the BPC can be paid with research grant funding, this means less money available to support actual research, and 2) that cost is enormously opaque. The oft-cited 2016 Ithaka S&R research reporton the cost of publishing a monograph presents a very wide range of costs associated with publishing a monograph, from $15,140 to $129,909. A more recent report from the Association of University Presses places the average cost at just under $20,000. These numbers include widely disparate inputs for staff time across every significant function from acquisitions, to development and production, then marketing and sales.

Are these actual “publishing costs” or a reflection of total business operating costs, which might be laden with poor practices? In my view as a 20-year publishing industry veteran, if it costs the publishing house, on average, $20,000 to produce a monograph, and in cases much, much more because of permissions, design, etc., that would be regarded as highly inefficient. To be fair, most BPCs are below $10,000, but I believe a case can be made for a much lower actual cost of acquiring, producing, and selling a high-quality academic book, based on my experience at a large publishing house and in several small, specialty publishing start-ups.

A Different Approach to Funding Open Access

A different model for funding open access would be to include it as an operating cost covered through revenue realization. All publishing houses have a mix of product models across print and digital that encompass single title and collection sales. As a proposal, what if five percent of the total revenue generated across all these sales was directed to funding open access?

Funding Open Access: How Much Does It Cost?

A model such as the proposed would benefit from full transparency in direct publishing costs, and it would require pricing for all publisher product models at or below par for the industry. The publisher could share actual book production cost inclusive of all pre-production costs, editorial services, design, developmental and copy editing, paging, proofing, and final production; in short, all actual book production costs minus acquisition costs and marketing and sales costs. In my view, this represents the actual cost of publishing a title. Acquisitions, marketing, and sales can be efficient or inefficient and are nearly impossible to allocate to a specific title without putting the proverbial thumb in the air. Every six months, the average publishing costs by line item could be shared on the publisher’s website

The five percent of revenue set aside in the same six-month period could then be allocated to fund titles released as open access at the published per title book production cost. For example, $200,000 in revenues would render $10,000 toward open access publishing, which would support two titles at $4,000 with a surplus of $2000 rolled over to the next six-month period of book production cost accounting.

This is effectively a hybrid publishing model and will not satisfy the aspirations of those seeking a fully open access publishing ecosystem. But I cast my publishing gaze across much more than the publishing of research and scholarly monographs and I acknowledge that many, many authors want to earn royalties.

Open Access Publishing: Who Gets Published?

The publishers’ author agreement would give the author the choice to opt in or opt out of consideration for open access publishing. This is a first in, first out model. It is not a guarantee that the book will be published open access, but it is a promise to the author that opts in that they will hold a place in line for their title to be published open access or converted to open access post-publication. There is an important exception to the first in, first out rule. An editorial board, could vote to move a title to the front of the line if there is a compelling social reason to do so. Consider, for example, the emergence of a pandemic and how this might shift publishing priorities in the public good. A model such as this is “equity rich” in that the author chooses to publish open access; not the publisher choosing who gets published open access.

This is a proposal for a new form of funding and publishing open access that is based on transparency and equity. It is a hybrid model of sorts, but it assumes an efficient and effective publishing house selling content at or below average market pricing and then publishing with quality and care. It is a model that puts all authors on equal footing, regardless of their home institution and the universities’’ capacity to contribute to what are effectively membership models. And it is a model that does not rely on grant funding, university funding, nor authors paying out-of-pocket BPCs. It is, of course, not perfect, but it is different and should serve as a discussion starter.

Discussion

11 Thoughts on "Guest Post — Funding Open Access Book Publishing: A Different Approach"

For clarity’s sake – is the proposal to reduce operating margins by 5%? It seems you are proposing no new revenues, but a reduction in a press’s margin?

Yes, I’m struggling with several aspects of this proposal as well.

First, it requires “selling content at or below average market pricing”. This seems counterproductive to me. If I make a superior product, higher production values, better editorial services, I’m still required to sell the product at or below average pricing. Which seems to incentivize cost-cutting and lower quality. Further, if publisher A sells a book for $10 and publisher B sells a book for $100, then publisher A only has $0.50 to put toward OA where publisher B has $5.00 to put toward OA. Again, this seem counterproductive to the goals here.

Lastly, I remain confounded by the desire for cost transparency in this (and many OA) policy models. There seems absolutely no need for an expensive and ultimately meaningless transparency exercise to be added here, other than to satisfy the curiosity of some customers who fear that they are being hoodwinked. Pricing is never set by costs, rather it is set by value. For the purchaser of a chair, it should not matter how much each nail cost the carpenter, rather what matters is the design and comfort of the chair. Is it worth the price you are required to pay for it? As the Plan S transparency policies have shown, the end results of such effort are meaningless as each publisher allocates costs differently, and one can lump anything under vague categories like “overheads” or “development”.

Hi David,

“Pricing is never set by costs, rather it is set by value.” In my experience pricing is set by expected margin, competitor pricing comps, acceptable indsutry expected price increases and, yes, by the customers perception of the value. I suggested this model would require pricing at or near market pricing (i.e. average competitor pricing) rather than higher so as to avoid the possible perception of pricing in the cost of publishing open access. If my price is the same as my competitors, and I am sending 5% of that cost to funding open access, I am doing it through margin management, not pricing acceleration.

this approach seems to consider OA a sort of “charity” for an Academic publisher

I believe this presents an alternative to be discussed and considered as David noted, some Fully OA journals have also considered a central fund/kitty that is contributed to – the challenge seems to be how to heard and align all the cats and manage the program with publishers in an equitable way?

Appreciate you sharing your thoughts David, putting you head above the turret – also like the Lived Places books you are publishing

“A different model for funding open access would be to include it as an operating cost covered through revenue realization”

I find this proposal rather disturbing as it takes OA publishing hostage and makes it conditionally linked to arbitrary revenue targets that publishers extraneous to academia think they are owed. I would venture to suggest that peer-network academic publishing will eliminate superfluous intermediaries seeking to extract ever mounting fees from both authors, readers and society at large whilst producing nothing of value themselves.

I think it’s high time we moved past tollbooth economic models. We do not live in the middle ages anymore, nor are books compiled word for word by hand in a wooden printing press.

This an interesting approach, but I am confounded by Mr. Parker’s concentration on what he calls direct costs, which apparently do not include such very real expenses as the costs of health insurance, phone bills, etc. How are these to be covered? But perhaps I am misinterpreting the proposed model?

Hi Lynne, I believe a publisher has many, many expenses not specifically tied to publishing a book. And I beleive, at least in a hybrid publishing models such as I propose, a publisher has many ways to generate revenues beyond a BPC. By allocating only those post acquisition and pre marketing and distribution costs to the “direct costs” of publishing a book to establish the cost of producing an OA book, I am removing much of the “grey” area in publishing cost reporting that stands behind BPCs. It’s controversial, and not for most publishers I know.

what happens when you get a unicorn title that’s in huge demand, globally important and relevant, real profitable, it’s fueling your five percent OA fund, life is good… and then comes the time to flip that golden goose to OA because the author opted in?

do you stay true to your first in first out principle and tank your whole business? or do you start making exceptions to the rule?

essentially my hunch is this model ultimately keeps the most valuable and in-demand titles closed in perpetuity (and those are exactly the ones that should be made OA posthaste), while only the niche least-read non-profitable ones end up getting the OA treatment.

Maybe, but only at the risk of the publisher acting in opposition to its public and stated practices as a publisher. I know this happens, but when it does the publisher loses credibility with authors, librarians, etc. Business can and does persist as usual, but the taint remains. Why not choose to prioritize integrity and mission over profit?

because in this model OA mission is directly linked to revenue — ideally you’d have your harry potters, bibles, twilight sagas and 50 shades of gray (academic edition) bringing the cash in, take the 5% (or even more) and put it towards OA publishing and furthering your mission. more revenue = more OA titles

but if you flip those most sought for titles — your rich and steady streams of revenue — to OA, you’re compromising your ability to keep delivering on your OA mission in the future. less revenue = less OA titles

either way it’s a lose-lose situation in terms of integrity unless i’m fundamentally misunderstanding the proposed model