Amid all of the excitement and trepidation surrounding artificial intelligence (AI), there is one big question for our industry that seems to rise above the rest: Are scholarly publishers primed to become the critical content suppliers for the big Generative AI companies such as OpenAI, AI21 Labs, NIVIDIA, and Anthropic?

Are Academic Publishers One of the Big Winners of Generative AI?!

The biggest issue with many of the current Generative AI models, including the versions of GPT, is the source of their training material and the quality of their answers. While the incredible power of LLMs is self-evident, some of the outputs such as those derived from regurgitated Reddit posts leave much to be desired.

For many real world purposes (and the public good), we need verified, high-quality, peer-reviewed content being fed into LLMs so that the best possible outputs will emerge on the other side. If we continue relying on general purpose AI models whose sources tend to be mysterious, we run the risk of rubbish in = rubbish out. Real world medical, business and legal applications require much higher degrees of accuracy and reliability in order to be turned into viable, fit-for-purpose products. In other words, trust.

For high-stakes, high-value projects, it is only natural that governments and corporations will look to scholarly publishers for high-quality, verified content. The AI companies are likely to look to big-name scholarly publishers as much for the content as for the brand and trust of being endorsed by the scientific community.

For the big publishers, this is nothing new. Elsevier has been working on models that use information gathered from Elsevier’s extensive repository of clinical evidence, combined with clinical, financial, and operational data, to suggest the best course of care for physicians. Just last week, Scopus, Dimensions, and Web of Science announced new conversational AI search products. Interestingly, many of these models are actually considered SLMs (small language models), which are more targeted as opposed to the ‘general’ models taking the world by storm.

Will other publishers be able to monetize their content in a manner that can be licensed and productized effectively?

Which publishers are primed to succeed?

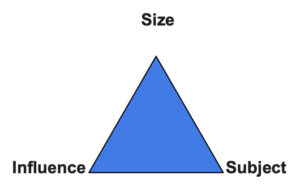

LLMs require large data sets and it is reasonable to expect that use cases will be driven by quantifiable and evidence-based areas from international publishers with a vast content set. The success of these strategies will be dependent on the size, influence and subject areas of the respective publishers.

The larger presses are more likely to have the resources and expertise to grapple with this kind of move at first, and smaller publishers may consider learning from their experiments (assuming there is some transparency and reporting) to see where they might be able to provide added value.

On the other hand, smaller publishers shouldn’t immediately count themselves out. “No matter the size of the data set, the relevance of the data is what really matters”, says David Myers from Data Licensing Alliance. “There are small publishers that are the most highly ranked in their specific discipline. As such, companies looking to build out AI solutions are seeking these publishers out first rather than the Elseviers of the world because without them, there is no true comprehensiveness to the trained data.”

Might a strong industry player be interested in licensing many small collections from small to medium size publishers and license as part of a larger data set?

How can publishers leverage and monetize their content?

License, Build, or Wait?

Traditionally, publishers license their content to relevant parties to read and digest. It is yet unclear whether use of content is covered under ‘fair use’ and will require additional licensing. For now, it seems that AI use is yet just another benefit to companies looking to license content from scholarly publishers. In turn, publishers may be able to increase their service offerings and add additional value to the companies, organizations, and governments that license their content. “As a matter of US copyright law, courts are more likely to rule in favor of copyright owners when licenses are available”, says Roy Kaufman, Managing Director, Business Development at Copyright Clearance Center.

However, this doesn’t necessarily need to be the only way that publishers leverage AI. There seem to be a few different ways that scholarly publishers are using their own content to build such models.

- Team up with the big AI players

While the appeal of building a tool in-house might seem attractive at first, most organizations in the scholarly publishing community don’t have the core technology or personnel in place in order to pull it off. Recently, Clarivate announced a partnership with AI 21 Labs as part of its “Generative AI strategy to drive growth”. Could this be a sign of additional big partnerships in the works? Will smaller publishers have similar opportunities? Or might they go through some of the big data or rights aggregators?

- Data licensing plus

Publishers can potentially monetize their content, but it is unclear how exclusivity might be handled and with what counterparties. Also, when will content owners maximize their licensing revenues? Some of these companies may ask for publishers to take an even larger and more active role in checking and giving feedback on the quality of the LLM outputs.

- Build LLMs in-house

Down the road, as the ability to create custom LLMs becomes simpler and cheaper, publishers might be able to use their content to create products and validate projects they are working on to further the mission of their society or maximize return for their shareholders. The resources required in order to make this happen probably limit this possibility to a small handful of publishers for now, but this could change with the quick proliferation of open LLM models.

Sit tight and wait

Some publishers are waiting to see what happens with other publishers before jumping in. This space will face considerable litigation in the upcoming years and it is understandable that publishers might not want to be dragged into a protracted legal battle. In addition, some publishers may want to wait to make sure that there really is a big enough market opportunity to capitalize on and that the added value of their content over the generic large language models is tangible enough in order to invest the time and resources required to make it happen.

The challenge with waiting is that the market will move forward and those who do wait may find their opportunities taken by more fast-moving competitors.

A setback to OA publishing?

In a world where peer-reviewed content holds value for Generative AI companies, the question arises whether content that is locked behind a paywall has greater value than OA content. The answer to this question may depend on the specific license that the OA content is published under and to what extent AI companies partner with OA publishers to create a direct feed of content.

Will publishers who still have a lot of content locked up, such as IEEE or NEJM, retain the most valuable assets? Will publishers that limit licensing to more restrictive terms such as CC BY-NC and CC BY-NC-ND have revenue streams denied to those exclusively using CC BY licenses? “Some publishers may be less willing to accelerate the transition to full open access if they consider licensing content to generative AI companies to be a more lucrative or secure revenue opportunity”, notes James Butcher, author of the Journalology newsletter.

Part of the answer to this question might actually lie in understanding what these LLMs have already scraped and to what extent they were allowed to do so. The question of whether the ingestion, without any sort of consent or negotiation, of massive reams of content is even legal is very much undecided. Recent deals such as the one between the AP and OpenAI suggest that, whenever possible, these companies want to proactively come to arrangements as opposed to battling it out in court.

As Niko Pfund, President and Publisher at OUP USA, puts it: “As with many new technologies, the question is less whether it can be done, but how it should be done, and we’ve already seen litigation on this question, which will likely struggle to keep up with what’s happening in practice, given the breakneck pace of developments.”

What about the authors?

In addition, there is a question as to who stands to benefit from these deals. Could authors receive income from their work via a CMO (Collective Management of Copyright) license, regardless of the agreement they have with the publisher? Most OA policies require copyright to remain with the author, but most publishers who do this also make them sign an exclusive license so the publisher is the only one that can license the works to others (or they make them publish it under CC BY terms).

If there is no revenue share, will there be a public outcry from authors whose work is being used again for the commercial gain of the publishers? Will there be a researcher who takes a page from Sarah Silverman’s book and takes on the Generative AI companies or the publishers they work with? If publishers do pursue this business strategy, will it push more academics to break the shackles of publishers and publish on their own? Will more journal editors quit to protest the imbalance of power?

Alternatively, publishers could invest in creating platforms for authors to publish their content for free so that they can use the content for their models.

The lone banana problem — can publishers cooperate to actually create good LLMs?

In a recent blog, Daniel Hook, Director of Digital Science, describes his difficulties in trying to get Midjourney to produce an image of a single lone banana. The issue that he raises is that even the most advanced Large Language Models have blind spots or areas of information that are missing. That problem may be exacerbated if each publisher licenses content on their own, as any single publisher rarely covers the entirety of knowledge on a particular subject area. While small data sets can sometimes outperform larger data models, the more complete coverage an LLM has of a particular field, the more complete and robust the resulting outputs should be.

So who actually has the content? Is there a company or institution with enough trust from different publishers as well as access to the data required to bring content from different publishers under the same roof and create an LLM whose outputs are truly beneficial? Could an industry group such as STM or ALPSP fill in the gap? Could Wiley do some experimentation on their own and then rope in some of the publishers they work with in their partner services division?

Conclusion

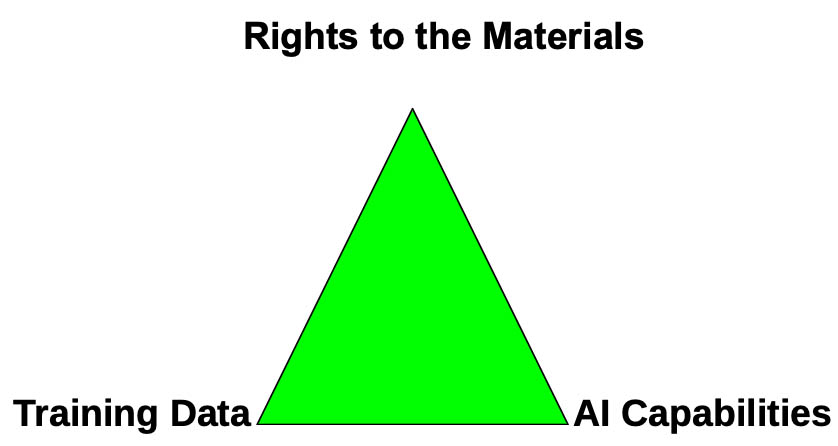

My colleague Roger Schonfeld suggested a golden triad is required for scholarly publishers to make an LLM project successful:

High-quality structured data is needed for input and some publishers have made a more concerted effort around these issues than others. For publishers who don’t know where to start, getting your metadata sorted out should be a priority. Ideally publishers should be aiming for fully structured data, but even having validated data in the form of structured XML files can be a good start. Companies such as CCC have systemized this process and work with the industry via their RightFind XML service. Others, such as Data Licensing Alliance, serve as marketplaces for content regardless of form and leave it to licensees to manage ingestion.

In parallel, publishers need to carefully consider what materials they want to license — out and in — including what rights they want to hand over and to whom. Finally, they need to figure out who has the AI capabilities to successfully pull off such a project and what their benefit would be to the process.

AI can leverage scholarly content to create a countless number of products and the more use cases that can be created the more value it will have. It behooves publishers to make their content as relevant as possible in their respective disciplines and consider how they want to be part of the move towards a Generative AI world.

If our curated content is as valuable as I believe it can be when properly leveraged, might we even see GenAI companies looking at scholarly publishers as potential targets of acquisition?

***My heartfelt thanks goes to David Myers, Roy Kaufman, David Crotty, Roger Schoenfeld, Niko Pfund, James Butcher and Leslie Lansman for their ideas and comments on the various drafts of this post. As I am not a copyright expert, any mistakes or inaccuracies in this area are mine alone.

Discussion

6 Thoughts on "Will Building LLMs Become the New Revenue Driver for Academic Publishing?"

Thanks for the thoughtful contribution to this space. I wonder if, as in both graphic design and in the entertainment industry, if those who actually create the content you reference, in this case, authors (researchers and patients in medical publishing), will seek their fair share in the monetization of their data used to power subsequent models emerging from its use, or perhaps seek stronger intellectual property protections instead as this work becomes more conspicuous?

In theory, I would expect an outcry from the author community if their content was again being monetized without recompense. That being said, many academics tend to be hyperfocused on their own publications and career advancement and may not have the time or energy to start taking on publishers. My anecdotal experience is that most authors don’t understand the IP they are signing over when they publish their articles, they are just happy to be finished with the process.

Isn’t this already the case? For most subscription journals, content is monetized in exchange for the services rendered to the author (the Gold OA model changes this to the author paying directly for those services). Not to mention all the journals that have extensive rights licensing programs already in place, as well as advertising. How is licensing content for AI training any different?

Maybe it will be different in terms of public perception? The ‘Sarah Silverman’ effect?

Maybe. But I didn’t see much outcry when journal articles were licensed to IBM for its Watson product:

https://group.springernature.com/gp/group/media/press-releases/springer-nature-collaborates-with-ibm-watson-/16060474

Great article and excellent questions. Will be challenging to answer them. A problem that has plagued other industries before – but will now be a lot more prominent – is the costs aspect. Costs related to running the infrastructure required to cater to tens of millions of people globally are gargantuan. Microsoft and Google haven’t found the solution for this just yet. Secondly, if anyone cares about the environment and climate change, it’s probably wise to dive into that aspect of this technological innovation as well. It’s an inconvenient truth for sure.