Editor’s Note. Today’s post is by Christopher A. Barnes, Reem Khamis, Yvette D. Hyter, and Betty Yu. Christopher is Assistant Professor and Digital Publishing Librarian at Adelphi University, where he oversees the institutional repository and the University Libraries’ open access publishing program. Christopher is the Production Editor for The Journal of Critical Study of Communication and Disability (JCSCD). Reem is Professor of Speech-Language Pathology and director of the Neurophysiology in Speech-Language Pathology Lab at Adelphi University. Reem is Co-Managing Editor for JCSCD. Yvette is Professor Emeritus of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences at Western Michigan University, owner of Language and Literacy Practices, LLC, and co-managing editor of the Journal of Critical Study of Communication and Disability. Betty is a Professor in the Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences and a Co-Managing Editor of JCSCD.

While higher rates of endogeny can help indexes identify journals being used for self-promotion, nepotism, or other unethical ends, endogeny itself should not be equated with them. Literally meaning growth from within, endogeny can be the result of a narrow or new field of research. Indexes should therefore avoid using the rate or percentage of endogeny as a standalone criterion for exclusion or delisting.

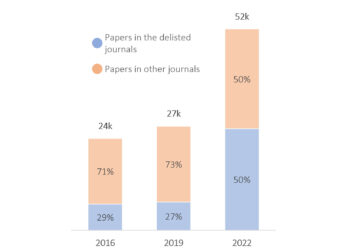

The problem of predatory publishing and the quality of open access (OA) scholarly journals have been hot topics for the last few years, especially since the pandemic brought increased scrutiny to the ways that scientific knowledge is vetted before and after publication. There has been an uptick since the end of March 2023 when Science reported that Clarivate was removing several open access (OA) journals from their Web of Science (WoS) index over quality concerns. As readers of The Scholarly Kitchen will know, Clarivate delisted 82 journals – including major ones by large OA publishers Hindawi and MDPI — after a review using their set of 28 selection criteria (see Christos Petrou’s guest post “Of Special Issues and Journal Purges”).

Editors and publishers rely on such publicly available lists of criteria when applying for inclusion in indexes as well as when designing policies and procedures for new journals, as in our case. Getting our new diamond OA journal indexed in WoS is a goal and we are therefore familiar with the criteria. But we are more familiar with the application guidelines for the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ). Given its prominence and the role it often plays in the institutional vetting of journals, we believe it is more urgent to us to get indexed in DOAJ than in WoS. It was therefore disappointing and concerning to learn that our journal is eligible for inclusion in WoS but will likely not be eligible for the DOAJ until we publish our third or fourth issue. Why?

Our first issue did not meet the DOAJ’s endogeny requirement by exceeding the allowable percentage of articles authored by an editor or reviewer. While the WoS guidelines don’t speak to it, the DOAJ stipulates that “endogeny should be minimised” as part of their “quality control process” and stipulates that “the proportion of published research papers where at least one of the authors is an editor, editorial board member or reviewer must not exceed 25% based on either of the latest two issues.” This particular language is actually new, having been updated at the end of April, possibly in response to the conversation sparked by the WoS delisting. The previous iteration of the policy placed the cap at 20%, “based on the research content of the latest two issues.” While the higher percentage might make it seem like the change amounts to a loosening of the endogeny requirement, this must be balanced against the adjustment to the way the percentage is calculated. It is now determined by evaluating the authorship of research articles in either of the latest two issues rather than both of them combined, meaning that each issue must meet the endogeny threshold independently.

The DOAJ does not explain its reasons for this change, simply calling it a “clarification.” Given the current debate over how to judge the quality of a journal and identify predatory or problematic publishing practices, we can guess that the move was made with the goal of making it easier to spot them. But we would rather not have to guess, and therefore encourage the DOAJ to be more transparent regarding the rationale behind both the policy and its specifics. We also believe exceeding the endogeny percentage should result in further evaluation to determine whether the number actually indicates a problem with that particular journal. For example, are submissions with an editor as an author receiving preferential treatment in the form of suspiciously rapid review or are they being reviewed by individuals with an undisclosed conflict of interest? Are editors being listed as coauthors on papers they had little or no involvement with so as to increase the chance of publication or the speed of review? If a journal is following all ethical guidelines and best practices in its submission and review processes, a higher rate of endogeny should not be taken as evidence of a lower quality publication. Knowing what indexers are looking for would also help less experienced editors develop workflows which prevent such unethical behaviors from happening.

The minor change to the DOAJ endogeny policy likely went unnoticed by most in the OA community, but it was major news for us as the editors and publisher of a new OA journal working on our first issue. Since we are looking forward to applying for inclusion in the DOAJ, we have been referring to the application guide regularly. Thanks to their high standards for inclusion, getting listed in the DOAJ confers legitimacy on new OA journals. Given this gatekeeping role, we believe that the DOAJ’s criteria for inclusion should be as clear and transparent as possible. Furthermore, we challenge the equation of endogeny with editorial bias, nepotism, and low-quality scholarship. Endogeny can actually be a good thing when understood in its literal sense as new growth beginning from within. It can also be necessary for the development of a new or narrow field of study.

Endogeny rates as red flags for unethical behavior

Upon discovering the change to the DOAJ’s policy, we did some research into the history of their endogeny requirement and studies of endogeny within scholarly publishing. Using the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, we found that the language about endogeny was first added to the application guidelines between 15 June and 28 July of 2021. The language read: “The proportion of published papers where at least one of the authors is an editor, editorial board member or reviewer, or affiliated to the journal’s institution must not exceed 20%, based on the research content of the latest two issues.” The next iteration of the policy cut the language about affiliation with the journal’s institution, and as already described, the current version raises the percentage to 25 and calculates it on either of the last two issues rather than both of them.

The implementation and development of the DOAJ endogeny policy corresponds with increased awareness of the problem of unscrupulous editors who use OA journals to publish shoddy scholarship by themselves and their peers in order to inflate their citation counts and perceived prominence in the field. A few months before DOAJ added endogeny to their quality control process, Locher et al., (2021) published “Publication by association: how the COVID-19 pandemic has shown relationships between authors and editorial board members in the field of infectious diseases.” In it, the authors identify “self-promotion journals” as “a new type of illegitimate publishing entity” in which scholars publish inordinate amounts of their own work within journals they edit, engage in agreements with other editors to quickly publish each other’s work, and do it all at the expense of rigorous peer review and high-quality science. The authors identify these journals by determining if any one scholar has been an author on more than 10% of all research papers, then examining the connections between such highly prolific authors and the other editors or the publishing organization. They found at least six journals in the field of infectious diseases whose editor-in-chief is also the journal’s most prolific author (p. 135).

In a follow-up article (Scanff et al., 2021) published by a group of researchers including many of those from the first study, the authors state they again found “a subset of journals where a few authors, often members of the editorial board, were responsible for a disproportionate number of publications” (p. 1). But the authors also caution against using these and other metrics alone to make a final judgment about the quality of a researcher’s scholarship or the integrity of a scholarly journal:

Some people are highly productive, and the speed with which good research can be completed is highly variable across research fields. Furthermore, authors may be represented in many papers because they play a key role in one aspect of the research, such as the statistical analysis, and senior researchers who oversee multiple projects may end up as authors on many papers. Similarly, shorter publication lags may occur simply because it is easier to find reviewers for eminent authors, or in a particular subject area, and/or because their expertise means that their papers require less revision. (p. 9-10)

The results of these research articles certainly provide support for the idea that high rates of endogeny can be a red flag and warrant further scrutiny. However, they also demonstrate why calculations and statistical analyses can only go so far in determining which instances of increased endogeny actually indicate a problem.

Further support for this view can be found at the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE). While they have been silent on the subject of endogeny, in May 2023 COPE published a new best practices document which addresses it in the context of guest edited collections. As they explain, “Guest edited collections can be more susceptible to organised fraud (e.g., peer review manipulation), financial conflicts of interest, greater instances of endogeny (papers published by guest editors and their close colleagues), citation cartels, and paper mills, and can lack ethical oversight” (p. 2). COPE therefore provides a long checklist of things editors and publishers can do to detect these behaviors, prevent bad science from being published, and retract it effectively if it is. The document does not include a percentage or formula for determining the proper threshold of endogenous content, instead opting to directly address the specific unethical behaviors it could signal, like undisclosed competing interests and extensive self-citations. The presence of endogeny in and of itself does not necessarily mean such problems are present, and COPE even states that “exceptions for narrow areas of research…can be made” (p. 6). We suggest that COPE’s “Best Practices for Guest Edited Collections” could serve as the basis for a new endogeny policy which moves beyond a statistical calculation to the specific unethical behaviors – “citation cartels, undisclosed competing interests, peer review fraud, identity theft” (p.8) – feared to be present.

Endogeny and the growth of a new field

We are writing in defense of endogeny because it can also exist at journals which have been begun by faculty with the mission of advancing a field of study that has been marginalized in their discipline and within which they are the pioneering experts. In such cases, it is understandable that the editors would be among the authors. We want to draw attention in particular to journals that have as their primary mission to give voice to minoritized scholars whose works are systematically excluded because they challenge the status quo. These scholars face institutional barriers that keep them from attaining the visibility and from building the bodies of scholarship they need to thrive in the academy. The journal can serve as a nurturing space for them and their scholarship, with editors and reviewers who share their critical perspective and desire to see the field grow. One might say that encouraging endogenous growth is one of the main reasons such journals are founded.

As a case study, let’s examine the journal we established: the Journal of Critical Study of Communication and Disability (JCSCD). The journal emerged to address the lack of scholarly venues for critical scientific studies related to people and groups who are marginalized and/or pathologized for their languaging and ways of communicating. The need for such a journal became more critical in light of calls for explicit recognition and dismantlement of racism in the Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences (SLHS) field after the murder of George Floyd. Many members revealed their frustration with the American Speech-Language-Hearing Assocation’s (ASHA’s) focus on performative diversity and lack of commitment to addressing institutional and structural racism. This includes restricting (and thus marginalizing) the publication of critical race scholarship in our field to special issues in ASHA journals, if they are published at all. By critical scholarship, we refer to the undertaking of scholarship that is sociopolitically contextualized, that fosters activism, that counters ideologies and practices that reproduce oppression and exploitation, and that reflects on one’s own positioning within the sociohistorical present. The JCSCD was established to foster critical scholarship in relation to language and disability. It aims to publish global perspectives and welcomes methods of inquiry that challenge positivist and colonial forms of knowledge, as well as papers that interrogate ingrained discourses and ideologies.

As the project evolved and developed, the journal became a point of gathering for the small group of scholars working on shifting scholarly work in the discipline from a positivist perspective to a critical one. Specifically, a perspective that is inclusive of the voices of people with the lived experiences of communication disability; that brings together studies focused on understanding social factors that restrict and oppress people with communication differences or disabilities; and that facilitates the advancement of decolonized knowledge production in order to guide inclusive and equitable practices affecting minoritized communicators. There are relatively few scholars in the field with a developed agenda within this critical perspective, and many of them are members of the journal’s editorial team. They joined as an act of resistance to the paucity of critical examinations of communication and disability. For the journal to develop and evolve, contributions from these members are necessary in order to model the work this journal aims to foster. Their contributions provide a powerful lens through which to reconfigure scholarship in relation to communication and disability. Their work provides a starting point that would be unique since they are setting out to shape new content and perspectives of studies.

A journal like JCSCD is trying to create a paradigm shift in an area of study and leveraging OA journals to do so. This type of effort may depend on — at least in the early stages — the contributions of its founders. That will raise its endogeny rate but should not exclude it from the DOAJ and other indexes on the grounds that this higher rate equates with lower quality and unethical behavior. We therefore encourage the DOAJ and other indexes to share the specific unethical behaviors they fear may be present when a journal issue has a high rate of endogeny, and to develop a means of detecting them. It will make it easier for legitimate journals to avoid unethical behavior associated with endogeny, and less likely that a high-quality journal serving a new field will be excluded for fostering growth and development from within.

The authors wish to thank Lisa Janicke Hinchliffe for the valuable feedback she provided on multiple drafts of this essay.

Discussion

3 Thoughts on "Guest Post – In Defense of Endogeny"

File under “unintended consequences” I suppose. Niche journals will attract articles from a niche community, and the journal internal citation rates will be high. Nothing new there: specialized scientific societies have long published journals that disproportionally publish and cite the works of its members. Seems like the root problem is getting to a human empowered to override the red flag criteria. Much like authors appealing a self-plagiarism rejection when the source of the “plagiarism” was iThenticate etc. flagging their own thesis or pre-print.

I was surprised to read that WoS will index a new journal after only two issues. That seems substantially loosened up from past experience.

Particularly frustrating for journals that publish a single, continuous issue for the calendar year, rather than more traditional ‘batch’ issues at regular intervals. We have had a similar rejection from DOAJ recently for a new journal that launched in early 2022. The 2022 issue/volume had over 25% of publications with an editorial board member listed as an author (all declared in the competing interest statement and fully removed from editorial processes). The 2023 issue has already organically addressed this, as the journal is now up and running and thus has a wider net to cast, but based on this information the journal won’t be accepted until after the 2023 and 2024 issue/volume closes (unless we change the publication model and go to small issues at set intervals).

DOAJ regularly works with journal editors in similar situations to discuss their journal’s eligibility, tackle concerns and try to find solutions. Editors are very welcome to contact us at helpdesk@doaj.org