Editor’s Note: Five years after it was announced, Plan S has had a significant impact on the scholarly communications landscape. cOAlition S recently released a new proposal, “Towards Responsible Publishing,” essentially meant to change course and replace Plan S. We asked the Scholarly Kitchen Chefs for their thoughts on the proposal.

Lisa Janicke Hinchliffe

As some readers of The Scholarly Kitchen know, I have been serving as the Project Director and Trend Lab Leader for the Charleston Trendspotting Initiative for a few years now, working with Katina Strauch and Leah Hinds to foster community-engaged conversations that explore trends and issues in the industry and forecast the impacts of these on scholarly publishing and academic libraries. Applying this kind of “futures thinking” to a possible policy change requires thoughtful analysis of current conditions, pressures on the system, risks, resources, and potential implications. It isn’t enough to think about the world as one wants it to be; one also needs to take a reality-based look at how the world actually is and what is likely to happen as a result of any given policy or action. Not all of what is likely to happen is what one wants to have happen. As I consider “Towards responsible publishing: a proposal from cOAlition S” and the current feedback survey, I am left with the uneasy sense that there is a lack of attention to the potential outcomes of the ideas being presented. For example, the vision asserts a causal claim: “Our vision is a community-based scholarly communication system fit for open science in the 21st century. This system empowers scholars to share the full range of their research outputs and to participate in new quality control mechanisms and evaluation standards for these outputs. This approach will ensure rapid, transparent dissemination of high-quality scientific knowledge.”

But, will it?

Or, will it fragment the scholarly record in such a way that results in rapid dissemination of separate components of a given project but a decline in the coherence and transparency of the dissemination system as a whole? Will scholars avail themselves of this empowerment? In light of the geopolitical breakdowns in scientific diplomacy, and suggestions that geowalling publications and data could be pursued if there is not reciprocity in openness, will open science even survive as a priority throughout the 21st-century? It’s worth having lofty ideals and visions; but, when putting policy into practice, considering changing contexts and thinking through both intended and unintended consequences would strengthen any next steps the cOAlition pursues. Otherwise, in a few years, it may find itself in a parallel place to the current situation in which its policies drove industry consolidation as well commitment to APCs and transformative agreements as financial models, which the cOAlition leadership now grapples with as problematic.

Rick Anderson

While there is lots to unpack and discuss in the latest cOAlition S proposal, I’m going to focus my brief comments on one particular aspect of the document: the coalition’s continued use of Orwellian doublespeak. I’ve called attention to the group’s previous foray into this realm, by which it established a policy that confiscates an author’s exclusive rights as a copyright holder (requiring those rights to be transferred to the general public) and called it a policy of “rights retention” – exactly the opposite of what it is. The new proposal contains what is perhaps an even more egregious example of this tendency: the claim that the new Plan S proposal represents a “scholar-led” initiative – whereas it is in fact a top-down, funder-mandated initiative that imposes the funders’ will on scholars and leaves the latter no choice about whether to adopt the program. (Beyond, of course, the choice not to apply for research funding.) Whether Plan S itself is a good thing on balance is a question on which reasonable people can disagree. But claiming that it is “scholar-led,” when it is in fact funder-led, funder-defined, and funder-imposed, is false and should be of concern to anyone who cares about truth. Making Plan S actually scholar-led would be a simple matter: change it to allow funded scholars to decide for themselves how, where, and under what licenses (if any) they will publish their work – and see where the scholars lead. But of course this would undermine the very foundation of the program. If it were scholar-led, it wouldn’t be Plan S.

Haseeb Md. Irfanullah

cOAlition S’s new proposal envisages a “community-based scholarly communication system”, where “scholar-led communication” is happening following a “scholar-led approach”. But it doesn’t explicitly define or explain “scholarly community” — a significant gap in this proposal.

Reading the five principles proposed, and believing that these are not targeting cOAlition S members only, I’ve tried to figure out the scholarly community. The community seems to include i) ‘authors’ of published research outputs (Principle 1); ii) ‘researchers’ with unpublished research documents (e.g., preprints) (Principle 2), as research assessment (e)valuators (Principle 4), and as one of the stakeholders of publishing ecosystem (Principle 5); and iii) ‘academics’ as peer-reviewers (Principles 2 and 3), as quality control standards setters and monitors (Principle 3), and as editors (Principle 3). Those who are not part of the scholarly community, but are mentioned in these principles, include Third-party suppliers/publishers (Principles 1 and 3), third-party infrastructure/service providers (Principles 1, 3 and 5), and research funders (Principle 5).

Despite this divide between the scholarly community and the non-scholarly community, Principle 5 brings them together, encouraging all to channel their resources to the proposed transition to a scholar-led system. But, it divides these two groups again by demanding commitments from the non-scholarly community to support diversity in academic cultures, disciplines, and traditions.

Defining a scholarly community based on these new cOAlition S principles has two major challenges. First, the authors, researchers, academics, peer-reviewers, and editors making up the academic community in fact do not represent ‘individuals’, rather the ‘roles’ that they play in the scholarly (publishing) ecosystem. That’s why we see the same individuals playing all these roles at different times, or even at the same time, but for different institutions, journals, and publishers. Also, although the proposed principles treat publishers as third-party service providers, in many small society journals, they are essentially those same academics acting as the publishers while representing their disciplines as well as their learned societies. The interactions and tensions among the different mandates, responsibilities, and demands from different roles make it challenging to define a concrete community.

Second, even if we consider that this community is made up of individuals, it is very heterogeneous, even within a discipline, based on gender, seniority, education, experience, knowledge, methodical approaches, geography, culture, and institutional/national socio-economic conditions. Increases in transdisciplinary research makes it more complicated to define a community which could collectively make decisions and take actions as envisaged by the cOAlition S principles.

Scholars’ institutions play a vital role in creating a scholarly community as they directly define and decide on academics’ livelihoods, workloads, assessments, and career progression. Although the institutions’ role isn’t explicitly stated in the proposed principles, it is elaborated sufficiently in the ‘Opportunities to engage’ section of the proposal, along with research funders’ role. cOAlition S’s proposal also outlines phased pathways toward what funders could do by changing the way they fund research, support changes in researcher assessments, finance the publishing of articles and peer-review reports, and bring stakeholders together to support a scholar-led publishing system. These ambitious, ecosystem-transforming pathways also don’t clarify the meaning of scholarly community. The example of the editor-based Publish, Review, Curate (PRC) model given in the proposal’s annex highlights individuals’ roles as authors and editors, not that of a community.

So, by not adequately conceptualizing scholarly community, I am not sure, if the cOAlition S’s proposal to transform the publishing landscape is really a community-based one. As a concept, scholar-led or community-based approaches may sound good, but may not be feasible given the multilayered heterogeneity within a community and the limited power individual researchers have to influence the currently inequitable publishing system.

Instead of a scholar-led system, we should talk about institution-led systems. Here institutions could be research or academic institutions, discipline-based learned societies, or even global transdisciplinary society of societies, such as International Science Council (ISC). As hubs of scholars, such institutions should be targeted as the change-makers of scholarly publishing. We should invest our time and effort in institutions, rather than in elusive ‘community’.

Roy Kaufman

Good intentions can pave many roads.

Can I agree with some of its premises and goals of the proposal? Sure, but “let’s fuel progress by making the scholarly record harder to find, with more burden on the author, with less obvious signals of validation and worse metadata” said no one, ever.

If enacted, the Plan S proposal would place enormous new burdens on authors. Not only would they need to agree upon and set the standards of quality control, but in “publishing” all scholarly outputs immediately and openly, authors would be forced not only to take responsibility for that quality control, but also for the application of interoperable metadata needed to enable each and every output to be discoverable and connected to final results.

A recent MEDLINE data quality assessment by some of my colleagues identified serious challenges in MEDLINE’s records. Would the Plan S proposal ameliorate or exacerbate challenges like this? Will it lead to greater discovery, increased linkage of articles and data, and greater usage and impact for authors? Traditional publishing outlets expend enormous resources on this and, while it has never been easier to disseminate content online, it also has never been harder for materials to be noticed and linked to, e.g., identities, grants, and institutions.

As mentioned in a Scholarly Kitchen post that I co-wrote in May with Jamie Carmichael and Jessica Thibodeau, “[s]cholarly research is complex and interconnected; change in one area can spark improvement or deterioration throughout the ecosystem (emphasis added).” In the transition to open science, stakeholders across the ecosystem acknowledge that authors should not have to shoulder an open access administrative burden that takes time away from their actual research. The scholar-led proposal from Plan S seems to overlook this, which is one of the few things that institutions, researchers, funders, and publishers seem to agree upon. Bluntly, being a great researcher does not inherently make you an adept publisher.

Additionally, the proposal’s call for the community — including service providers — to supply open tools and commit funds to sustain the model with little to no return-on-investment is unsustainable. While well-intentioned, this type of approach is a recipe for failure. Adding links, building metadata bridges, and enriching records have real costs that require significant amounts of money. With the required tools already available, a better approach is to invest in their adoption, not to duplicate work by creating new ones.

Scholarly communications are important, which is why its participants have such strong views. Getting communications wrong has real-world consequences, many of which are unintended. Let’s acknowledge this and work together to solve the challenges that we can actually solve without adding complications and entropy.

Angela Cochran

The recently published cOAlition S proposal raises an important question — what do researchers want when it comes to the future of research publishing?

One might argue that the research community has already answered that question. Plan S prohibited funded authors from publishing in the majority of journals. Still, authors continued to publish where they wanted to publish, and remained “compliant” by using funds from their universities rather than their research grants, alternative funding from coauthors, or green methods in subscription journals. Many journals made good faith attempts to try to move toward OA only to find that the majority of their authors prefer to publish under a subscription model.

Repeated warnings were raised that Plan S was more of a boon to commercial publishers than to anyone else. This proposal is, at least, a tacit acknowledgment that those warnings were right.

There is one thing publishers know for certain…researchers want to spend as little time on publishing activities as possible. Yet this proposal requires more effort from the research community in disseminating their research results using processes currently managed by journals.

Keeping this in mind, I am pleased that coupled with this proposal is an effort to conduct a survey with researchers. Hopefully, this consultation will help everyone understand whether researchers have any desire to invest the time and effort to run the research dissemination enterprise in their spare time.

Discussion

9 Thoughts on "Ask The Chefs: cOAlition S’s “Towards Responsible Publishing”"

Sincere thanks to the chefs for highlighting this proposal, and the associated consultation we are running on behalf of cOAlition S. While we are endeavouring to keep up with online commentary, I’d strongly encourage the contributors to this article, and anyone reading it, to submit your views via our online survey. This way I can guarantee your feedback will be captured and fed back to cOAlition S through a structured process of analysis and review. Most questions are optional and there’s a free text comment box at the end so this can be a copy-paste exercise if you’re short on time. You can find the survey here: https://survey.alchemer.eu/s3/90624212/cOAlition-S-towards-responsible-publishing

Hi Rob, I appreciate you highlighting this opportunity. But, answering the survey requires licensing one’s responses with a CC BY license and assigning copyright of some information to the researchers. These are compulsory conditions I cannot agree to. And, I really question the assertion that these are needed so you can legally process the data. I answer many surveys each week that do not require either of these things.

Hi Lisa, your response prompted me to take another look at the survey consent form and I agree with you that these conditions are more onerous than is necessary. We’ve now replaced the two conditions you mention with the following: ‘I agree to allow researchers in the project team to copy, store, analyse and publish any data or materials collected as part of this project in line with the permissions given above [in the rest of the consent form].’ Hopefully this removes any barrier to you and others contributing to the survey.

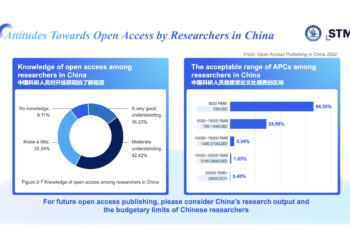

Nice article—thank you all. To Rob? I wonder whether the surveys to come will be revealing. There are plenty of existing surveys that measure researcher attitudes on open access, publishing, and related tangents. Piecing these together, it’s been clear for many years that these attitudes vary (often wildly) by region, field, career stage, age, institution, need, and more. So it seems to me misguided to think that all we need at this point is more evidence that will hopefully undergird new funder-driven one-size-fits-all solutions. Researchers want their work to get noticed, they want their work to make a difference, and they want to get credit. To me anyway, if we can work together around basic, evidence-driven principles like these instead of around ideological goals, we will find that a whole world of truly researcher-led opportunities await us on the road ahead.

Thanks Glenn, you’re right that researcher surveys won’t give us definitive answers, but they are the best (only?) tool we have for engaging with the research community at scale. In parallel to the surveys we will also be running eight stakeholder focus groups in December, and we are expecting to undertake further, more focussed, engagement activities in 2024. We’ll use the latter to dig further into the key issues that emerge from the early feedback survey that is open till 29 November.

There are no easy answers here, of course, but we hope that this process will give us a sound evidence base of quantitative and qualitative data to inform further iterations of the cOAlition S proposal.

A ‘scholar led’ academic publishing ecosystem already exists: journals owned by scholarly societies. These societies seem to strongly prefer the slow (= rigorous) editor-led peer review subscription model that this new proposal aims to eliminate.

Exactly. And they’re being driven en masse into the arms of large commercial publishing firms — in large part because initiatives like Plan S (and, in the US, the new and stricter OSTP requirements) are making it impossible for them to do business independently anymore.

Unintended consequences are a bummer.

Not sure the consequences were unintended.

If you wanted to support non profit scholar led OA, you would give money to non profit scholar led OA. You would then build them up to showcase scholar led OA as the epitome of rigorously reviewed high quality research.

If you wanted to support for profit commercial OA, you would roll out Plan S which adds a whole lot of requirements for things that OA advocates care about (specific CC licenses, 0 embargo etc) and builds no capacity for the things researchers care about (publishing in quality outlets that win them respect, fame and funding).

The whole thing has a very 1984 feel to it. We say we want open for all. Equity and fairness. No barriers to research. But instead, we put up more barriers and add bureaucracy. High quality and strict standards will give way for profits and low quality publishing. AI will help spread the bad research. Scholarly societies will eventually die without funding, and in the end, we will have a few giant commercial publishing powerhouses controlling everything.

In the name of Open