Editor’s Note: Every year as we enter the holiday season, we take a moment to pause and look back on the best books we encountered (not a “best books of 2023″ list, but a list of the best books the Chefs read during 2023 — the books might be classics, a few years old, or brand new). In recent years we expanded our list to include any sort of cultural creation or experience our Chefs wanted to share.

Here’s Part 1 of our list, Part 2 can be found here and Part 3 here.

Charlie Rapple

This year I loved Project Hail Mary by Andy Weir. You’ll remember 10 years ago everyone was reading his first book The Martian, about an astronaut left for dead on Mars, and the ingenuity by which he survives (it was recommended by Kent Anderson in The Scholarly Kitchen in 2014). Project Hail Mary (published in 2021) follows the same sort of formula, but don’t be put off: this time it’s not just about ingenuity in science, but also in communication. Our protagonist Ryland Grace wakes up in a spaceship with no idea who he is or what he is doing there. I will leave out the real spoiler details; suffice to say, he gradually remembers that he’s one of a team sent to save the world from a climate disaster (something is consuming the sun’s energy and causing catastrophic cooling on earth — a nice twist on reality). In trying to continue the mission, he finds himself in contact with another ship with another life form on it. We follow, with bated breath, as — tiny step by tiny step — they manage to start communicating. There’s loads of great sciencing too, but I loved the detailed think-through of how you would go about establishing communication with a life form that doesn’t have the same kinds of inputs or outputs as us. The emerging relationship between Grace and the alien is fascinating and touching. The whole thing is brilliantly imagined, entertainingly and accessibly written, and there’s an unexpected, delightful ending that, again, puts it a cut above The Martian.

This year I loved Project Hail Mary by Andy Weir. You’ll remember 10 years ago everyone was reading his first book The Martian, about an astronaut left for dead on Mars, and the ingenuity by which he survives (it was recommended by Kent Anderson in The Scholarly Kitchen in 2014). Project Hail Mary (published in 2021) follows the same sort of formula, but don’t be put off: this time it’s not just about ingenuity in science, but also in communication. Our protagonist Ryland Grace wakes up in a spaceship with no idea who he is or what he is doing there. I will leave out the real spoiler details; suffice to say, he gradually remembers that he’s one of a team sent to save the world from a climate disaster (something is consuming the sun’s energy and causing catastrophic cooling on earth — a nice twist on reality). In trying to continue the mission, he finds himself in contact with another ship with another life form on it. We follow, with bated breath, as — tiny step by tiny step — they manage to start communicating. There’s loads of great sciencing too, but I loved the detailed think-through of how you would go about establishing communication with a life form that doesn’t have the same kinds of inputs or outputs as us. The emerging relationship between Grace and the alien is fascinating and touching. The whole thing is brilliantly imagined, entertainingly and accessibly written, and there’s an unexpected, delightful ending that, again, puts it a cut above The Martian.Jill O’Neill

I warned David that I couldn’t pick just one title this year!

The Adventures of Amina al-Sirafi

The Adventures of Amina al-Sirafi

A ship’s captain has withdrawn from the sea to care for her young daughter and to keep out of the sight of those who she believes may hold grudges. She is drawn back into the world by the demands of a powerful old woman and is driven to reconnect with senior members of her old crew — her first mate, her navigator, her chief poisoner, an ex-lover. (The first chapter all by itself is a delightful attention-grabber.)

There are plenty of adventures and voyages here — not unlike those of Sinbad. As the reader, one encounters demons, monsters, and the elemental powers. But there is a strong narrative thread tying it all together. Where is the old woman’s granddaughter? What of the Moon of Saba?

This book by Shannon Chakraborty is the set-up of a new series, one that draws on Arabic culture in much the same way The City of Brass, The Kingdom of Copper and The Empire of Gold did. The story here doesn’t seem quite as complex as the books that made up the Daevabad Trilogy, but it does establish the personalities gathered around our brave sea captain.

The author knows when and how to bring in plot twists so that the reader is caught off guard. Magic is not always benign; generally speaking, it’s more likely not to be. And one should be cautious of any contract entered into with those wielding such powers!

If you choose to give The Adventures of Amina al-Sirafi as a Christmas present, be sure you order the British edition. The cover art and the end papers (Arabic navigational maps of the world) are striking.

This 2022 novel by Ray Naylor is an exciting example of speculative fiction but, if you try to speed through the action too quickly, you’ll experience mental indigestion. The book is not too dissimilar in some ways from such classics as Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed or C.S. Lewis’ Out of the Silent Planet, both narratives that examine the challenge of living side-by-side with those whose values we do not fathom.

In Naylor’s debut novel, he seeks to examine the various facets of how living creatures seek to communicate a sense of self and of tribe. On another level, the book has to do with sentience as encountered in machines as well as organic life forms. The challenges that Naylor puts forward are significant – the function of identity, the prioritization of artificial intelligence in a highly competitive and mechanized society, the vulnerability of humans living in such a society, and the violence of a dystopian world that has exhausted its resources.

At the same time, this is a novel that could easily be adapted into an action film. There are drones and submersibles and one or two battles at sea. There are scattered allusions to Jack London’s classic, The Sea Wolf. You are in the ocean depths upon occasion, but you’re also in a research lab on an archipelago off the coast of Vietnam. You are following as protagonists a female scientist, a hacker, and the victim of a press gang. Among the secondary characters are a set of automonks, an interesting head of security and a truly unique android. You may think you know who to root for, but there are plenty of opportunities to be proven wrong.

There is precision in Naylor’s construction of the narrative. Each of the 48 chapters is preceded by a paragraph of text from a fictional scientist’s work. (The reader is well-advised to pay attention to those.) Even the external book design has significance. Grab the hardcover from Farrar Straus and Giroux and note the inked page edges. There was a tremendous share of talent poured into this.

The above are two relatively light genre recommendations. Ping me privately and I will rattle off a dozen more titles and yet another dozen authors (living and dead) over which I mulled during 2023. This was the year I finally read Alberto Manguel’s A History of Reading, originally released back in 1996. From there, I went directly to his A Reader on Reading (2010) and the much shorter 2019 meditation, Packing My Library, both available from Yale University Press.

There’s a great deal of uneasiness currently about ordinary reading behavior — what books we read and why, our access to books, the amount of time spent with books, the social currents that drive publishing decisions, and the books that may not survive. For now, I will echo a thought from the preface of Alberto Manguel’s A Reader on Reading:

I believe there is an ethic of reading, a responsibility in how we read, a commitment that is both political and private in the act of turning the pages and following the lines. And I believe that sometimes, beyond the author’s intentions and the reader’s hopes, a book can make us better and wiser.

This year, more than ever, I have been grateful for the freedom to read at will.

Rick Anderson

As usual, I’m going in a slightly different direction because my book reading is pretty pedestrian and uninspiring (when I’m not reading review journals, I’m reading crime novels). But my music consumption is much more wide-ranging and potentially interesting, so instead of recommending books I’m going to recommend some of the best music releases of the year. I’ll start with a world-premiere recording of works by Vicente Lusitano. A well-known music theorist in his time, Lusitano is primarily remembered today — when he’s remembered at all — as very likely the first Black composer to have been formally published. His sole surviving collection of works, the Liber primus epigramatum, from which these ten motets were taken, was published in Rome in 1551. Lusitano was born in Portugal of mixed European and African parentage and eventually became a priest and a music teacher in Padua and Viterbo, and made his living through student fees (since paid clergy positions were available only to White men at the time). Throughout these marvelous vocal works you can clearly hear Lusitano paying tribute to Josquin des Prez, but at the same time he has developed a style distinctly his own — echoes of which we’ll hear later in the work of, among others, Carlo Gesualdo.

As usual, I’m going in a slightly different direction because my book reading is pretty pedestrian and uninspiring (when I’m not reading review journals, I’m reading crime novels). But my music consumption is much more wide-ranging and potentially interesting, so instead of recommending books I’m going to recommend some of the best music releases of the year. I’ll start with a world-premiere recording of works by Vicente Lusitano. A well-known music theorist in his time, Lusitano is primarily remembered today — when he’s remembered at all — as very likely the first Black composer to have been formally published. His sole surviving collection of works, the Liber primus epigramatum, from which these ten motets were taken, was published in Rome in 1551. Lusitano was born in Portugal of mixed European and African parentage and eventually became a priest and a music teacher in Padua and Viterbo, and made his living through student fees (since paid clergy positions were available only to White men at the time). Throughout these marvelous vocal works you can clearly hear Lusitano paying tribute to Josquin des Prez, but at the same time he has developed a style distinctly his own — echoes of which we’ll hear later in the work of, among others, Carlo Gesualdo.

Turning in a radically different direction, we have Rare Global Pop 1980s. Belgium’s Crammed Discs label has been releasing fun and oddball pop and experimental music since the early 1980s, when they burst onto the avant-rock scene with albums by Aqsak Maboul, Julverne, and the Honeymoon Killers. Over the past few years the label has been raiding its vaults and putting out a steady stream of reissues and compilations under the series title Crammed Electronic Archives. The series includes six EPs by the likes of Nadjma, Des Airs, and Maurice Poto Doudongo — a hugely varied list that embraces afropop, European postpunk, and Arabic electropop. But if you don’t want to deal with six relatively brief releases, consider picking up this 17-track sampler, which provides an excellent overview of this fascinating catalog project as well as some rare singles and remixes not included on the EPs. If you’re like me, though, you’ll want every track of every release.

Turning in a radically different direction, we have Rare Global Pop 1980s. Belgium’s Crammed Discs label has been releasing fun and oddball pop and experimental music since the early 1980s, when they burst onto the avant-rock scene with albums by Aqsak Maboul, Julverne, and the Honeymoon Killers. Over the past few years the label has been raiding its vaults and putting out a steady stream of reissues and compilations under the series title Crammed Electronic Archives. The series includes six EPs by the likes of Nadjma, Des Airs, and Maurice Poto Doudongo — a hugely varied list that embraces afropop, European postpunk, and Arabic electropop. But if you don’t want to deal with six relatively brief releases, consider picking up this 17-track sampler, which provides an excellent overview of this fascinating catalog project as well as some rare singles and remixes not included on the EPs. If you’re like me, though, you’ll want every track of every release.

And of course I have to include a reggae album. Here are the things I love about Berlin reggae band Tooth of a Lion: first, and most importantly, they deliver the heavyweight goods: tuneful old-school reggae in a rootswise style with maximum bass pressure. Second, they sing in German rather than awkward English. Third — and this is very important — they don’t put on fake Jamaican accents. Here’s what I like less: their debut, Sonne von unten, is an EP rather than a full-length album. (Of course, at 34 minutes long it’s about the same length as a typical 1970s reggae album.) It’s hard to identify highlights because each track here is excellent, but “Kaun Kaun Kaun” hits extra hard due to its showcase-style dub extension, and “Flaschensammlah” incorporates a galloping dancehall interlude that is lots of fun.

And of course I have to include a reggae album. Here are the things I love about Berlin reggae band Tooth of a Lion: first, and most importantly, they deliver the heavyweight goods: tuneful old-school reggae in a rootswise style with maximum bass pressure. Second, they sing in German rather than awkward English. Third — and this is very important — they don’t put on fake Jamaican accents. Here’s what I like less: their debut, Sonne von unten, is an EP rather than a full-length album. (Of course, at 34 minutes long it’s about the same length as a typical 1970s reggae album.) It’s hard to identify highlights because each track here is excellent, but “Kaun Kaun Kaun” hits extra hard due to its showcase-style dub extension, and “Flaschensammlah” incorporates a galloping dancehall interlude that is lots of fun.

Dianndra Roberts

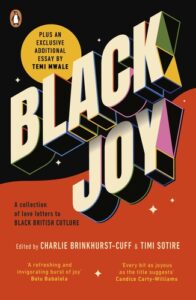

Black Joy edited by Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff and Timi Sotire

Black Joy edited by Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff and Timi Sotire

“Joy surrounds us. It can be found in the day to day. It’s what we live for. So why do we so rarely allow ourselves to revel in it?”

I picked up this book while walking around a bookshop — a place I find great joy getting lost in — and thought why not? I could always use some more joy and if anything I’ll learn a bit more about those who contributed to the book. I thought it would make a good read but I wasn’t expecting how much I would find parts of myself in some of these essays: the wonder that is the artist formerly known as Prince, memories of Choice FM — a staple of the community in 90s/00s London and when you finally have a Black colleague. The feeling of being home when you touch down on the plane and the Caribbean heat gives you a friendly slap or learning to cook traditional food with your elders. For me being able to make these dishes almost feels like a lifeline as I’m getting older. All these experiences filled my heart, and had me feeling seen — smiling and nodding at a book in public.

The joy in this book is one of individuality and community. It was a wholesome read to see the reflection of the ins and outs of the Black British experience that I am proudly a part of. It was fun to read how it has changed and in some ways is still the same across generations and spaces. With essays from Munya Chawawa, Leigh-Anne Pinnock, Diane Abbott, and more, each essay really is an individual experience from the discussion, structure, and style. Everyone can and should read this book — even if this is not your community there is joy to be found in the experiences shared and it’s an insight into humanity. There has long been a compulsion that the telling of the Black experience has to be one of struggle — and yes there is struggle, but there is also laughter, community, safety, and joy! There is a lot of joy to be had and told. These stories are just as important, so read them and share them.

Discussion

3 Thoughts on "Chefs’ Selections: Best Books Read and Favorite Cultural Creations During 2023, Part 1"

I’d been looking forward to the best reads of 2023 in TSK. Thank you for these wonderful suggestions.

On my end, two books that stuck with me this year, for very different reasons, were Jennifer Egan’s Candy House, and RF Kuang’s Yellowface. The first one imagines a not-so-alternative future, where a startup has made it possible to upload to an app our memories and make them public. The second — a hilarious satire of the publishing industry.

Crime novels (and other pedestrian best sellers) are my typical go-to as well, but I’ve been sprinkling in some non-fiction. Range by David Epstein was an absolute standout for me this year, and had/has me thinking about interdisciplinarity in every sense of the word. Highly recommend!

I am delighted to read that classics are also considered in the “Best Books we Encountered in 2023” list.

I returned to Barbadian literary artist and Caribbean scholar, George Lamming’s 1953 novel In the Castle of My Skin.

This Caribbean classic is a semi-autobiographical fiction which follows the life of the protagonist named “G” (as in “George ” for “George Lamming) in pre-independent Barbados.

Lamming is a literary genius as he subtly exposes the ideologies within this colonial society in order to awaken postcolonial consciousness within readers.

Recommended reading for all!