Editor’s Note: Every year as we enter the holiday season, we take a moment to pause and look back on the best books we encountered (not a “best books of 2023″ list, but a list of the best books the Chefs read during 2022 — the books might be classics, a few years old, or brand new). In recent years we expanded our list to include any sort of cultural creation or experience our Chefs wanted to share.

Part 1 ran yesterday, Part 3 is now available as well.

Joe Esposito

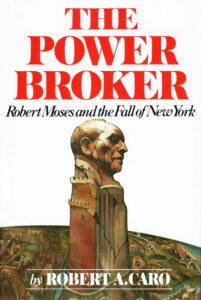

A friend urged Robert Caro’s biography of Robert Moses, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York on me soon after it was published in 1974. I looked at it, got distracted, and did not pick it up again until this past year. What a mistake: the book is a masterpiece. I was prompted to look at it again by a documentary, Turn Every Page (2022), on the relationship between Caro and his editor, Robert Gottlieb, which was produced and directed by Gottlieb’s daughter, Lizzie Gottlieb. I found the documentary to be informative, astute, and loving. The subjects deserve no less: what a triumph of authorship and publishing!

A friend urged Robert Caro’s biography of Robert Moses, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York on me soon after it was published in 1974. I looked at it, got distracted, and did not pick it up again until this past year. What a mistake: the book is a masterpiece. I was prompted to look at it again by a documentary, Turn Every Page (2022), on the relationship between Caro and his editor, Robert Gottlieb, which was produced and directed by Gottlieb’s daughter, Lizzie Gottlieb. I found the documentary to be informative, astute, and loving. The subjects deserve no less: what a triumph of authorship and publishing!

Moses, born at the tail end of the nineteenth century, was the principal architect and builder of the infrastructure of much of New York, City and State. The list of his accomplishments is stunning (think of parks, parkways, highways, bridges, even Jones Beach). I have lived most of my life in and around New York, and I now realize that it was all a house that Moses built. Moses was brilliant, an elitist, amazingly accomplished, arrogant, devious, racist, and contemptuous. He achieved power through brains, determination, lies, and intimidation. He was also immensely popular, as the public loved the parks and beaches he was masterminding. That popularity was the source of his power, as no politician — not FDR nor his nominal boss, Fiorello La Guardia (whom Moses referred to as a “little guinea son of a bitch”) — could afford to fire him. And thus the man shaped New York into what it is today, an automobile-centric city, with public amenities distributed unevenly to the various groups that comprise the city’s population.

The book exists on three levels. First is the biography itself, which is astonishing and disturbing at the same time. Moses is a creep! But people loved him because, as the book’s chorus says, he got things done. Every few pages I found myself reflecting on the similarities with Elon Musk.

The second level of the book is a history of New York, its political culture in particular, over five decades. The corruption and cynical politics are breathtaking; and hard as it is to believe, it was really worse then, in the age of machine politics, compared to today, when it is merely sickening. Some portraits are unforgettable: Al Smith, the governor of the state and huge supporter of Moses, and FDR, who does not come off well in this book, which characterizes him as devious, vindictive, and petty.

Finally, this is a book, on the meta-level, about Caro himself. It is a tour de force of journalism, astonishingly well researched, clearly written, and packed with the telling detail. Let me offer just one: in order to prevent the poor from getting to the new parks and beaches on Long Island, Moses connived to have the overpasses built too low to accommodate buses, which thus denied access to the poor who did not own cars. I wonder if there was anyone in New York government at the time whom Caro did not interview, any document he did not study carefully. This is why the Gottlieb documentary about him is called Turn Every Page.

I cannot recommend this book highly enough, but it comes with one caution: it is 1,700 pages long; the audio version is sixty-six hours. For some reason there is no e-book version. But it is worth putting in the time. I wish I had read it decades ago.

Tim Vines

I get suckered into buying too many business books in the airport. I’ve no emotional bandwidth for serious grown-up books, there’s never much good sci-fi, and I feel a nagging guilt that I should be doing something useful with all those hours on the plane. So I buy a book promising (as a theoretical example) to imbue me with the managerial wisdom of ancient wooden bowl carvers – and discover that these bowl carvers didn’t actually have all that much more insight into business management than the blurb on the back cover.

I get suckered into buying too many business books in the airport. I’ve no emotional bandwidth for serious grown-up books, there’s never much good sci-fi, and I feel a nagging guilt that I should be doing something useful with all those hours on the plane. So I buy a book promising (as a theoretical example) to imbue me with the managerial wisdom of ancient wooden bowl carvers – and discover that these bowl carvers didn’t actually have all that much more insight into business management than the blurb on the back cover.

Which is why Scaling People: Tactics for Management and Company Building by Claire Hughes Johnson is such a great contribution. It’s actually about management, it doesn’t try to shoehorn in a dubious metaphor from some other activity, and – despite its ominously boring cover – it’s a delight to read. I will confess that I’m only about 1/3 of the way through but have found every section so far both insightful and actionable, which is a truly rare combination in a business book. Now to take up bowl carving.

Todd Carpenter

For I have known them all already, known them all:

Have known the evenings, mornings, afternoons,

I have measured out my life with coffee spoons;

We live out our lives in a world that is measured and quantified. The alarm goes off at 5:50 AM so we can get the kids off to school on time. We catch the 8:15 AM train to New York or a 20:40 flight to London. On our way to the office, we dutifully try to remain not that much faster than the posted speed limit of 35 MPH. The email attachment is returned because it exceeded the 30MB attachment size limit. After work, we try to squeeze in a trip to the gym to do a 5K run on a treadmill so that we can lose that “spare” ten pounds. In the scholarly publishing world, we obsesses about our own set of metrics, such as impact factors, h-index, altmetric, or download figures. In an increasingly digital world, the ability to focus on minute incremental changes from one state to the next has become both a symptom and a symbol of our current age.

We live out our lives in a world that is measured and quantified. The alarm goes off at 5:50 AM so we can get the kids off to school on time. We catch the 8:15 AM train to New York or a 20:40 flight to London. On our way to the office, we dutifully try to remain not that much faster than the posted speed limit of 35 MPH. The email attachment is returned because it exceeded the 30MB attachment size limit. After work, we try to squeeze in a trip to the gym to do a 5K run on a treadmill so that we can lose that “spare” ten pounds. In the scholarly publishing world, we obsesses about our own set of metrics, such as impact factors, h-index, altmetric, or download figures. In an increasingly digital world, the ability to focus on minute incremental changes from one state to the next has become both a symptom and a symbol of our current age.

Despite our obsession with quantification, have we really ever spent time thinking about how these metrics derived? What makes a meter a meter, a pound a pound, or why on earth is a mile equal to 5,280 feet? It makes rough sense that a foot was derived from a rough approximation of the size of a human foot, or the hand as a measure that is now only relegated to expressing how tall a horse is. If we are quantifying the passing of time by seconds, minutes and hours, where do these systems come from and how are they established? This is the focus of a fascinating book I started out 2023 reading. Beyond Measure: The Hidden History of Measurement from Cubits to Quantum Constants by James Vincent lays out the history of how various measurements began and how they have developed. The process of formalization has grown from averages, estimates and ever precise measurements, the world has grown ever closer and more consistent based on our structures of measurements. As we increasingly demanded greater precision and our scientific understanding of the basic physics of our universe, the standards that have developed are increasingly based on physical constants. Our common understanding of time is no longer driven by a fraction of the average length of a day of a place outside London in the UK, or the movements of the sun across the sky as it had been historically. Today, our basic unit of time, the second, is defined based on the fundamental properties of the caesium 133 atom and the frequency of its vibration (i.e. radiation). Vincent traces other attempts to ground the standards that quantify our lives in basic physical constants, such as distance and

Years ago, I had a lovely discussion with the manager of a NASA registry of exoplanets, who upon learning that I was involved in standards setting, excitedly said she needed my assistance in standardizing the different methods of measuring time by two different schools who use different standards for calculating the presence of an exoplanet. One group used sun-based time, while the other group used earth-based time. After describing the physics involved (it is far more complicated than simply the 9 minutes it takes for light to get the extra distance between the two planets), I realized that the problem wasn’t that of standards, rather it was about the social agreement of which measure to use. Fundamentally, Beyond Measure is really about the same social forces that drive us to need and want measures we can trust and that we all agree upon. At the end of the day (GMT 0:00:00), we all want to be sure that we’re on the right train, headed in the right direction to make our meeting on time.

Roy Kaufman

Sometimes, especially when I am travelling or when a lot is happening in the world, I struggle to connect with books. In those times, magazines, newspapers and podcasts absorb my then-especially short attention span. When this happens, I look for a good “world-building” novel to break the cycle.

Sometimes, especially when I am travelling or when a lot is happening in the world, I struggle to connect with books. In those times, magazines, newspapers and podcasts absorb my then-especially short attention span. When this happens, I look for a good “world-building” novel to break the cycle.

When I consider of world-building novels, I typically think of the first in any great (or for that matter, reasonably good) fantasy series such as JK Rowling’s Harry Potter or the His Dark Materials by Phillip Pullman. Occasionally however, someone is skilled at world-building when working with our world. To me, the master of this is James McBride. I previously read Deacon King Kong, about life in Brooklyn projects in the late 1960s, where a church Deacon shoots a young man who he used to coach in baseball but who is currently dealing drugs.

McBride’s new book, The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store, is about the relationships between Black and Jewish residents of “Chicken Hill,” a neglected-by-the-town neighborhood in rural Pottstown, Pennsylvania to which these outsiders have been relegated. The story begins with a mystery of found human remains, a dancing Hasidic man, and a quasi-biblical flood. It then moves backwards to a time not so long ago when the town held an annual Klan parade and the residents of Chicken Hill here expected to make themselves scarce. In modern times of progression and regression, McBride reminds us of people’s complexities.

Discussion

3 Thoughts on "Chefs’ Selections: Best Books Read and Favorite Cultural Creations During 2023, Part 2"

Nice recommendations! Joe, like you, I picked up The Power Broker when it came out but didn’t finish it. Good reminder to go back to it.

Roy, thanks for the McBride recommendation, too.

Thanks for the warm comment on the Moses bio. As for the James McBride title, my wife is reading it now with her reading group. She loves it. She and I read McBride’s previouis novel, “Deacon King Kong,” together last year and came away with deep admiration.

Let me know if you like it Julia.