In early August of 1789, Rebecca Foster was raped on three different days by three different men in her home on the outskirts of the small town of Hallowell, Maine. The wife of the town’s minister, she charged these men publicly, and there was a trial. None of the men was punished; Rebecca and her husband, Isaac, moved away, first to another town in Maine and then to Maryland. Then as now, it was unusual for rape to be charged, not least to go to trial. Then as now, rape created spirals of trauma.

I can assert that Rebecca Foster “was raped” not because the historical record for this case is clear, but because of the extensive scholarship on the subject this is a reasonable interpretation. The primary sources include Foster’s description of the rapes to witnesses at the time, particularly to the local midwife, Martha Ballard, who recorded it in her diary, and the trial record. From the extensive work of generations of historians and others who have worked on this and associated cases I also know that the cultural and structural forces were such that accusations of rape were rare, and that sexual assaults and those rare accusations both regularly followed traditional patterns of gender and racial hierarchies of power. I also know how even more rarely were such assaults prosecuted and then rapists convicted. I know quite a lot about how the court system worked, how rural Maine’s economy operates, what the social structure and the religious culture of this small town looked like. I know about how midwives’ played a role in the work of adjudicating sexual violence just as they were essential health care – including reproductive care – providers. And that they clashed with the emergence of male doctors, whose track record particularly as regards reproductive health care was comparatively poor. Mostly, I know about Rebecca Foster’s eighteenth-century case from the extraordinary work of a single historian and the infrastructure of research that preceded and then followed her work on Martha Ballard, the Maine midwife who wrote about Rebecca Foster’s charge: “Mrs Foster Has Sworn a Rape.”

Last month I read a comment from a fellow historian on social media wondering why a popular historical novelist in a prominent media interview hadn’t credited the scholar who is nearly synonymous with the topic she’d fictionalized. Because it’s right in my own research wheelhouse, I started reading and thinking more about this case and about questions of attribution and generosity, particularly as they pertain to the fragile humanities research infrastructure. As we experience unprecedented (in scale, not kind) attacks on historical research and teaching, it struck me as particularly important to open a more general conversation about the contexts and costs of the invisibility of humanities research. I am particularly concerned with the implications of leaving the vast infrastructure of research invisible to a public largely unaware or unconcerned with how much hard-won knowledge, including creative endeavor, that research has facilitated.

To be very clear, I am not accusing the novelist of anything more than a lack of generosity. I am an enthusiastic and regular reader of historical fiction; my favorite novels are by authors who work their fiction the way they work their history – layered, and deeply informed. I wrote, for example, in an early Scholarly Kitchen best book round-ups about my deep appreciation for Rachel Kadish’s The Weight of Ink; only later did I discover this marvelous interview with JSTOR about her research for the book. I confess to be thoroughly biased about Deborah Harkness’s work because she is one of my favorite people as well as writers, though I’m obviously in good company as a fan of her hugely popular All Souls series; my favorite remains Shadow of Night in part because her incredible knowledge and skills as a historian of 17th century England and science are so apparent in every lush detail. I often learn more even about places I thought I knew well when I read a wonderful historical novel. Susan Scott Holloway’s book about Mary Emmons, the woman Aaron Burr enslaved and married, for example, blew me away despite my having read lots in the world of Hamilton-adjacency. I read Kaitlyn Greenidge’s Libertie, a novel about the daughter of the real life Black doctor in late 19th century New York, Susan Smith McKinney Steward, twice in a row it was so evocative. I could go on, and on. So it’s not that I’m hostile to historical fiction – quite the contrary.

And I think it’s important to note, too, the obvious point that novelists are working to create something fresh and new, and often or mostly imagined, even if inspired from any number or types of other art, people, and places. And sometimes ideas are just in the air – no one has a commanding claim to ideas that many people come to seemingly at once; we are all breathing the same air and often we’re just coming to conclusions together. Still, it is also true that scholars can rightly feel abused by journalists and creatives who use their work without attribution and that this may happen more often to women and to people of color.

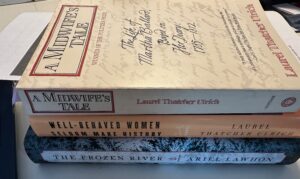

So after that set of caveats, what I’m talking about here is the really risky behavior of not recognizing the extensive research foundation on which a lot of work is built. In 1991 Laurel Thatcher Ulrich published A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785-1812. It was a big deal. Not because it won a Pulitzer Prize, though that was cool, too, but because A Midwife’s Tale reflected the hard work of women’s history for generations to call attention to the significance of the daily work that made communities and sustained families. It was a call to a different kind of history, not only of wars and politics, of John Adams and George Washington, but Martha Ballard, a woman who delivered babies, who had babies, who contributed immeasurably to her community and whose story would have been nearly invisible if not for the diary she kept that a 19th century historian of Maine described derisively as too dry and dull – and unimportant. Ulrich’s title was a bit of a feint, and any characterization of it as simply a biography is wrong. It’s a rich history pulled from a close and complex analysis of all the dry and dull details to reveal the fullness of a community. Including of Rebecca Foster’s rape.

Having inspired scholars, students, community histories and creative folks for more than thirty years since Ulrich’s book, Martha Ballard is now easily accessible online in multiple formats. A google search for “Martha Ballard midwife” returns a bazillion hits (okay, more than 39,500 in .01 seconds is the actual report). A big project team developed Dohistory.org, a website about the Ballard diary and the histories it reveals funded by the NEH and the Maine Humanities Council that in 2000 won the award from the American Association for History and Computing multimedia prize; that year it was also a Yahoo! Pick of the week. It still works, mostly. The site is now maintained by the Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University, a key center for advanced digital history. The scope and sheer volume of primary sources shared on the site for investigating Ballard’s diary and the history of Hallowell is extraordinary: the fully transcribed and searchable diary of Martha Ballard, from the work of an early 20th century husband and wife team, as well as multiple other relevant diaries, maps, newspapers, other public records and secondary sources. As I was browsing the online sources and materials about Ballard including event of midwives and local officials in Maine commemorating Ballard, I also came across a neat text mining project by historian Cameron Blevins.

Filmmakers Laurie Kahn-Leavitt and Richard Rogers also worked with Ulrich and another big team for more than five years to produce A Midwife’s Tale for PBS as part of its American Experience series. It’s a gorgeous dramatization, and it stars actor Kaiulani Sewall Lee, whose Maine family knew Martha Ballard. I still hear colleagues talk about teaching with the film as well as the book. Martha Ballard has been an ongoing key topic and resource for scholars and teachers alike; a JSTOR search turns up more than 500 references, including on the history of midwifery, reproduction, and sexual violence. The history of midwifery is bound up with the modern histories of gender and sexuality; although JSTOR is easily accessible to anyone who registers to read on the site as well as through libraries, scholars have been working and writing in public about the history of midwifery and reproductive sexuality in this and other historical periods on such sites as Nursing Clio, a collaborative scholarly blog about gender and medicine (and where you can find a lot of smart references to Martha Ballard).

In short, there is no shortage of material that the research on Martha Ballard could and has inspired. The novel in question here is The Frozen River by Ariel Lawhon, described on the jacket flap as “a gripping historical mystery inspired by the life and diary of Martha Ballard, a renowned eighteenth-century midwife who defied the legal system and wrote herself into American history.” The interview that my historian colleague was responding to was one with NPR’s Scott Simon. In it, Lawhon described how she came across Ballard, sitting in a doctor’s office looking for something to read and found in “a small devotional. So I opened it to that day’s date. It was August 8, 2008. And I read the story of a woman named Martha Ballard, who had delivered over a thousand babies in her career and never lost a mother.” But you know, the Daily Bread devotional for that day didn’t start with Martha Ballard. It started with Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, noting that she was awarded the Pulitzer prize, and describes the prize-winning book as based on the diary of Maine midwife Martha Ballard.

There are so many echoes of Ulrich’s first chapters in Lawhon’s, maybe because the Kennebec river as it flows through Hallowell is such a rich and important character in Ballard’s diary, and maybe because the theme of her conflicts with the doctors is so poignant. Certainly Ulrich wrote creatively, even lyrically about Ballard; she was not by any means a passive stenographer as Lawhon’s acknowledgements suggest when she notes that Ulrich’s book offers “the facts – and nothing but the facts.” That’s damning with faint praise to be sure, but is also a mischaracterization of how historians work, and most assuredly of how Ulrich was working. Ulrich in fact described her work as bringing forth the stories that were in the margins. Not unlike how Lawhorn describes her own efforts.

“The Rebecca Foster story led me to think about the entire diary differently; how many other stories might there be hidden in those cryptic entries about visits?”

Laurel Thatcher Ulrich on DoingHistory.org

“I have always tried to stick very closely to the facts of history. And then I would find my story in the cracks, the conversations that are not recorded, the betrayals we don’t know about.”

Ariel Lawhon to Scott Simon, NPR’s Weekend Edition, December 16, 2023

I have not sought out every possible place where Lawhon’s more extensive attributions or discussions of research method could be lodged: I looked to the acknowledgements and notes in the book, to her website, to that NPR interview, and to few other interviews I could find easily. I also could have but didn’t ask either Laurel Thatcher Ulrich or friends who are accomplished authors of historical fiction what they think about the ethics of attribution generally and in this case. Ulrich is well used to people’s fantastical uses of her work. She wrote about the many appearances of her line about “well behaved women seldom make history” (including in products like a mug my stepmom bought for me at a women in computer science event) and the course of women’s history in her book of that title.

That’s because this piece really isn’t about calling out this particular author or comparing one to the other; it is about the nature of our interdependent knowledge, and what happens when we are so relentlessly overwhelmed by the narrative of independent production. A recent piece in The Atlantic about acknowledging all the people including editors who contribute to book production seemed to strike a chord with authors, editors, and readers alike. Interestingly, this piece was prompted in part by a review of Dan Sinykin’s Big Fiction: How Conglomeration Changed the Publishing Industry and American Fiction, which argues in part that mass production of course elides the extensive collective labor of production. Martha Ballard’s history didn’t fall like rain, available to be collected; it was built like any edifice. I name the builders and describe the edifice here because I fear for what we are losing when we don’t.

Discussion

7 Thoughts on "“Mrs. Foster Has Sworn A Rape”; or, What Do We Owe? Generosity, Attribution, and the Perilous Invisibility of Research Infrastructure"

Hi Karin. What an interesting story. Thank you for highlighting it. You certainly make a valid point about the fragility of the research infrastructure. In this case, however, wouldn’t you say that the infrastructure is actually pretty good, and one almost has to work hard NOT to find Ulrich’s fingerprints all over the Martha Ballard story? I realize, of course, that you don’t want to get into motives and intentions but I can’t help but think that an oversight like this would actually be more understandable if it had happened 30 years ago before we had today’s digital infrastructure.

Hi Peter! Thanks for your comment. It’s so hard to know what to make of this case, so yes, I came down on the side of simple failure of generosity. But also true that the research infrastructure is vulnerable both to upkeep (thank goodness for the RCHNM maintaining do history.org) but also to lack of credit. What’s not acknowledged is invisible is unimportant is unfunded.

Here’s what Martin Amis wrote in the acknowledgments of his 2004 novel, Yellow Dog.

This is a work of unalloyed fiction, but several of the areas it touches on involved me in some light research. The following books proved especially helpful, and I should like to thank their authors (and/or editors).

Robert Lacey’s Royal (Little, Brown) and Alison Weir’s Henry VIII: King and Court (Jonathan Cape).

Tony Parker’s Life After Life (Secker & Warburg) and the ‘Mad Frank’ Trilogy by Frankie Fraser (as told to James Morton) – Mad Frank (Little, Brown), Mad Frank and Friends (Little, Brown) and Mad Frank’s Diary (Virgin).

Andrew Weir’s The Tombstone Imperative: The Truth About Air Safety (Simon & Schuster) and The Black Box, edited by Malcolm MacPherson (HarperCollins).

Judith Lewis Herman’s Father-Daughter Incest (Harvard University Press) and Head Injury: The Facts by Dorothy Gronwall, Philip Wrightson and Peter Waddel (Oxford University Press).

That’s a great example of fair and generous attribution. One of the novelists I listed, Susan Holloway Scott, has a list of acknowledged scholars for my favorite of her books that looks like a PhD field exam. I always really appreciate reading more in the author notes section. I think it makes the novel more interesting.

Thanks for pumping up my “Wants to Read” list!

Yes, mine too!

I’m a nerd for source acknowledgements in fiction. I definitely notice when they are not included, and I admit I give the author a big side-eye. But I have usually already read the book at that point. Maybe I should be checking first!