Editor’s Note: Today’s guest post is by Heather Weltin, HathiTrust; Alison Wohlers, California Digital Library (CDL); and Amy Wood, Center for Research Libraries (CRL), who are coordinators for the CDL, CRL, & HathiTrust Shared Print Collaboration (more commonly called the “CCH Collaboration”).

Authors’ Note: Our goal in writing this blog post is to set the stage for expanding how we think about the future of shared print. We were first inspired to do this by David Crotty’s 2019 post about why community-owned infrastructure needs business strategies. This will be one of a two-part series, the second of which will introduce some ideas for change. We invite our colleagues and peers to engage with us in contemplating these ideas, either via the comment section or offline.

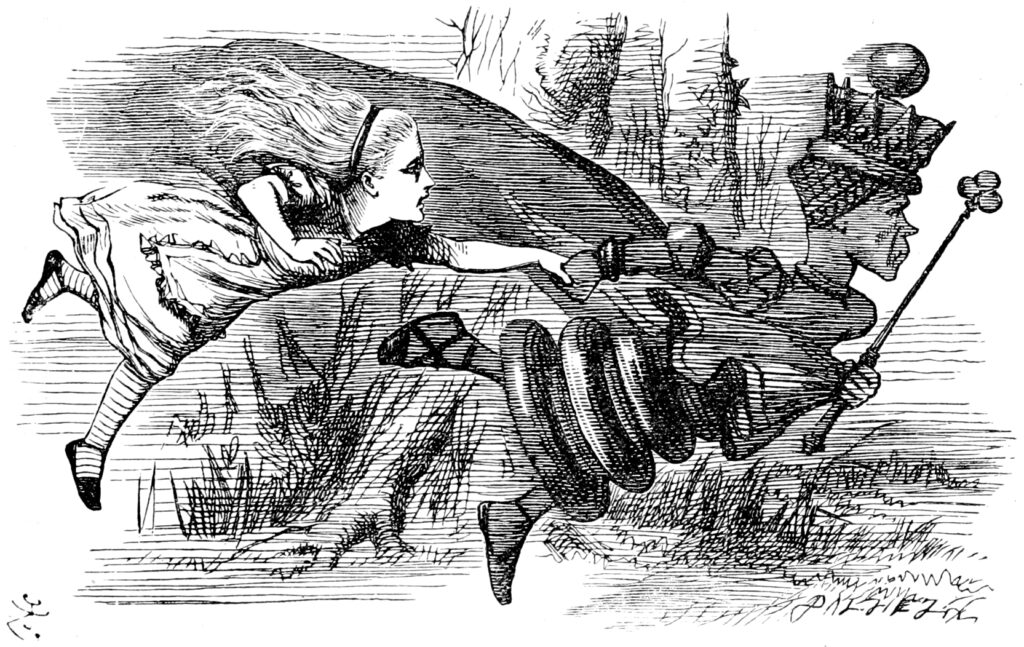

David Crotty’s Scholarly Kitchen post, Building for the Long Term: Why Business Strategies are Needed for Community-Owned Infrastructure, inspired us to apply a similar lens to the sporadically high-profile, fast-growing, and complex problem space of shared print — specifically the effort to build a national shared collection by networking amongst individual shared print programs. The number of libraries committed to cooperative solutions for print preservation and management has grown considerably and, just in the last several years, we have seen major breakthroughs in building partnerships at the national level in the US and Canada. And yet, there is something in it all that feels like we’re running in place. We find ourselves, to riff off Katherine Skinner’s July 2019 blog post Why Are So Many Scholarly Communication Infrastructure Providers Running a Red Queen’s Race, moving at top speed year after year but are seemingly still not that far from where we started.

Applying Skinner’s framework demonstrates that shared print has a sustainability problem. Libraries’ ability to steward print collections in the future is being compromised by how we manage them now. We believe that sustainability is both a mindset and a lens through which we need to view, analyze, and act upon the needs of the libraries. Our use of the word sustainability is aligned with the United Nations’ definition: the aim to meet current information needs without compromising future needs (informational, environmental, economic), and with ALA’s call to action for librarians to be catalysts, connectors, and contributors to community resilience included in their Report of the ALA Special Task Force on Sustainability. We have to evolve our shared print strategy to align with the core values of libraries, and to increase the value proposition of print collections.

The what and why of shared print

Shared print is a body of collaborative activities undertaken to ensure that print collections are retained and available for current and future users. Shared print builds on the value of long-standing library partnerships and services, including interlibrary loan and shared storage, by adding a layer of formal agreements that individual libraries make to retain (not withdraw) and provide access to a specific set of print resources through a designated time horizon.

Libraries invest in this activity because print collections continue to be relevant to the scholarly communication ecosystem. Crist and Stambaugh’s 2014 survey of ARL libraries surfaced three general rationales for retaining print collections that are generally available and preserved digitally: re-digitization, supporting research consultation of the print form, and guarding against catastrophic loss of collections. Overall, patterns of use and digital availability, coupled with space and resourcing opportunity costs, have driven the adoption of shared print strategies amongst academic libraries (Dempsey, et al., 2013).

Throughout the twentieth century, a number of strategies to create shared collections, including shared storage facilities, collaborative collection development, and rationalizing the number of copies of low-use material were undertaken. But none took hold at a scale large enough to create a national impact. In the 1990s, with the growing networked digital collection and changing economies of acquisitions and impact on perceptions of value of the print collections, the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) recommended the establishment of regional repositories to steward print resources, and the creation of inter-institutional networks of information-sharing to reduce duplication and to delegate the responsibility of managing print collections. The result is what we think of as shared print today.

As early as 2003, at the Preserving America’s Print Resources summit, there were calls for greater coordination among regional programs. Despite these calls, shared print programs continued to develop as unrelated efforts with only a fraction of the full corpus accounted for. Collections retained and services developed targeted the needs of their member libraries. This state has persisted despite the establishment of two national alliances, the Rosemont Shared Print Alliance and the Partnership for Shared Book Collections, which were born of the desire to work across the growing number of regional and local shared print initiatives.

In a parallel effort to support shared print’s transition to a new phase of integration and interoperability, in January 2020 our organizations formed the California Digital Library, Center for Research Libraries, and HathiTrust (CCH) Shared Print Collaboration. The Collaboration has acted in a facilitative role to build relationships and encourage discussions across functional and organizational silos. A 2021 summit of library leaders, shared print experts, and service providers surfaced common aims for working across functional and organizational silos to embed shared print across the collections lifecycle. In 2022, the momentum continued with partnerships across libraries, consortia, and service providers effectively advancing the vision of embedding shared print into the collections lifecycle. But, in 2023, we struggled to see systemic change in embedding shared print in the work of all functional areas across the lifecycle of collections. In addition, a joint task force recommended that the two national alliances merge to meet “the organizational, structural, and cultural challenges of shared print programs” including reducing redundancy of effort and workload on individuals.

How the Seven Barriers Manifest in Shared Print

Using Skinner’s list of seven barriers for academy-owned and academy-led infrastructure, we have grouped them to underscore the ways these barriers work in tandem to hinder shared print progress.

Resourcing

- We are chronically underfunded and understaffed; support is contingent and attention is fleeting.

- We often compete with one another for scarce resources.

Chronic underfunding and understaffing are problems for libraries in general. The 2022 Ithaka US Library Surveyrevealed a new lens for understanding overarching resourcing trends: while resources are not necessarily lacking overall, the prioritization of those resources is shifting. Further analysis indicates a shift from expenditures for collections to services. This change particularly threatens shared print because of our business models’ reliance on membership.

Shared print programs and initiatives incur costs that libraries generally share through a membership model. These costs vary and while one of the national federations is working on a calculator, we do not have the information or transparency needed to effectively compare and understand shared print costs.

Several large shared print programs relied on significant grant funding for the first few years of their operations, which subsidized the initial cost, but not the ongoing expense for individual libraries. For programs embedded in the services of existing consortia and membership organizations, some raised special funds from amongst the members to support the work, others redirected existing capacity, and some also underwrote the early costs to build momentum and incentivize participation.

The Western Regional Storage Trust’s (WEST’s) transition out of grant funding and into a pure membership model – with accompanying fee increases to maintain similar service levels – resulted in cancellations, loss of revenue, and eventually, adjustments to service levels. While WEST has reached equilibrium with right-sized services and is growing its membership once again, the program remains vulnerable in its dependence on a membership model. The Eastern Academic Scholars’ Trust (EAST) managed the transition from grant funding more effectively through steady and intensive membership growth. For programs where consortial capacity was redirected, the sustainability of the ongoing shared print effort is subject to reprioritization and the availability of member funds.

Membership growth has been one way to maintain low costs after grants or other subsidies end, but it has its limitations. There is a limit to how much a regional or local program can grow while still providing effective services to all members and adhering to its “regionality.” In addition, if all or many programs see membership growth as the sustainability solution for the future, we are going to run into detrimental competition as multiple programs recruit the same libraries and libraries are participating in multiple programs. This will result in duplicative work and expense for the libraries without significantly expanding the services they receive.

Skinner observes that programs often compete for resources and argues for “incentives for alignment and disincentives for duplication of work.” In shared print, we are prone to duplicative work and do not have effective disincentives in place to help us avoid it. Instead, we are all trying to innovate along similar lines, particularly around technology, and measure success in our member and retention counts. This duplicative work involves resources which we know are already competing with other services across our library budgets, which can lead to undervaluing or deprioritizing shared print overall or moving support and attention elsewhere. Rather than focusing on growing membership and duplicative efforts, the shared print community could spend time focusing on collaborative efforts like broadening the scope of items committed, reaching optimal duplication of committed copies of items, or developing new and better services that leverage the shared collection.

The Innovation Delusion

- Our planning and strategy focus more on innovation than maintenance.

The significant role that grant funding and membership have played in shared print business models has encouraged us to emphasize the ways we can innovate rather than sustain. In his 2019 reflection on library collaborations, Roger Schonfeld observes, “Our profession has chosen to recognize and reward leaders for creating new organizations. There is as a result an incentive to create a new organization above and beyond the needs of the libraries themselves.” For years, this has worked to seed new shared print programs. The number of new shared print programs between 2010 and 2015 gave the work a center of gravity, a significance, and a sense of innovation it might not otherwise have had, because they connected networks of libraries that might not have worked together. These benefits initially carried us all forward on a wave of enthusiasm. But there is a counterbalance and unintended consequence of that momentum as Stearns and Wohlers highlighted in Shared Print on the Threshold, “While ever more prolific, varied, and collaborative on standards and best practices, shared print collections remain awkwardly siloed from program to program, and more detrimentally, from other library services and infrastructure.”

This siloing has led to competition for library attention and resources, and encouraged us to continually come up with something flashy and new to keep us ahead of the rest of other shared print programs and library collaborations and to provide an illusion of success. Maintenance is not captivating to funders or libraries, but it is essential to achieve sustainability and meaningful innovation. The key to finding the effective balance between innovation and maintenance requires imagining innovation and maintenance as two points on a continuum. Opportunities for innovative maintenance lie within the continuum.

Business Sense

- We depend on leaders who are not trained in basic business functions.

- We lack assessment and accountability.

- We don’t know how much money we currently spend on [shared print] as a field, nor are we measuring how actions we take impact that number.

Librarians have had to diversify their expertise as more services are gathered under the umbrella of information specialists. Our libraries and collaborations have created complex products and services requiring sophisticated business and financial management (e.g. WEST’s AGUA tool, CRL’s PAPR registry). But we continue to come up against a lack of business experience, strategy, and business resources as we try to move forward hosting and maintaining them, investing in their further development, and governing them collectively.

Fiscal and administrative hosting is an essential but complex need for our various collaborations and these have associated costs. Library consortia have some capacity for hosting strategic programs that resonate with their visions and missions, but that capacity is limited. Just this year, fiscal hosts for a regional program, one of the national shared print federations, and another national collaborative program – outside of but similar to shared print – ended their hosting responsibilities. Hosting these programs (and being hosted) takes significant resources and is not a core service of most libraries or consortia. As we look to a sustainable future, we need to build better business models that make hosting sustainable for both host and hosted program.

Amplifying the problem of sustaining the business side of these programs is the challenge of measuring the cost of operations and their impact for libraries. Shared print’s foundation is in ensuring future access. It is an effort with a long horizon for return on investment without clear measures to gauge this. Using access statistics as a measure of success has not been fruitful. In the early days of shared print, the focus was on high overlap content and there was enough redundancy across library collections that the access benefit of shared print was decidedly just in case. Even now shared print programs do not appear to play a significant role in facilitating access to content (see Figure 1 in this EAST analysis). To date, we lack the tools or data to measure either immediate or potential impact.

Conclusion

Libraries are simultaneously limited and creatively fueled by the trilateral tension to calculate the demands of legacy collections, current needs, and future possibilities in every collection stewardship strategy. A common driving force of all of library innovations has been collaboration at scale – taking place above the group or consortial level. Each of us have been deeply involved in the important library collaborative effort to ensure the preservation and access of print materials in library collections. Yet, each of these efforts has fallen short of evolving into sustainable models that effect needed change over time.

Skinner put it well when she stated, “…we have to work at it – beginning with building a strong understanding of where we are today so that we can make sure that in the future, the faster we run, the farther we go.” In shared print, we can’t keep running the Red Queen’s Race and we are at a pivotal moment where choices we make can take us beyond these barriers. With the Rosemont Shared Print Alliance and Partnership for Shared Book Collections merger on the horizon, leadership transitions abounding, and organizational strategic planning running rampant, this could be our golden moment to forge a new and sustainable path. We’ll talk more about this in the follow up blog post. We hope you’ll join that conversation as well.

Discussion

2 Thoughts on "Guest Post — Shared Print Down the Rabbit Hole"

This is a really compelling and thought-provoking post – thank you for it. As someone involved in collaborative collection building for digital preservation, I feel our communities have much to gain by working more closely together rather than in parallel. Terrific to see this thought leadership from CDL, CRL, and HathiTrust!

Thanks to colleagues Alison, Heather, and Amy for shining a light on the important work of shared print for Scholarly Kitchen readers. I look forward to the follow-up post and recommendations they have.

I do, however, have a couple of comments to share:

First, I take issue with your conclusion that the graph on the EAST website demonstrates that shared print does not “play a significant role in facilitating access to content”. Nothing in the methodology of this very limited analysis could support such a conclusion, particularly as today’s discovery environments do not readily make shared print content discoverable. The statement that “using access statistics has not been fruitful” is an accurate one, but it does not mean that shared print could not impact access in the future nor should we conclude that this is not an important byproduct of shared print since if we do not protect and preserve our print content, it certainly will not be accessible.

I also believe that your interpretation of the sustainability of shared print – or lack thereof – does a disservice to many of the programs that have focused on sustainability and recognized its importance. Shared print today protects and preserves only a small portion of the print content housed in libraries in the US and Canada. Sustainability of shared print cannot be achieved without continued growth. Today’s models are likely to undergo change – possibly and maybe hopefully radical change – in order to adapt and evolve. In fact, I would argue that the work CCH began working with vendors and service providers to collaborate more deeply around embedding shared print in library workflows demonstrated ways in which today’s models for shared print must evolve. I hope that work will be revitalized in the future.

Much of the cost of sustaining shared print today is the result of its being siloed and not integrated into the ways in which libraries manage their print collections. While addressing business models is always appropriate – and EAST and other programs have, over the years, modified theirs in support of sustainability – the future of shared print depends more on how it is integrated into library operations. Eliminating the need for continued collection analysis work, for example, would have a significant impact on operational costs of shared print and could allow programs to either be absorbed more naturally into other library services, or allow those programs to serve more and more libraries at reduced costs thereby increasing the proportion of print content protected and preserved.

Finally, and this as well as my statements above are personal ones as my retirement as Program Director for EAST is well known and I do not want to be seen as speaking for EAST, I very much hope that the forward momentum that shared print has seen over the last decade is not interpreted as standing still but as evolving (maybe more slowly than we might like) and that with continued hard work there is no reason to believe that evolution cannot continue, particularly with the insightful work of organizations such as the California Digital Library, HathiTrust, and the Center for Research Libraries.