Two months ago, Nina Jankowicz (author of How to Lose the Information War and How to Be a Woman Online, and executive director of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Disinformation Governance Board during its brief existence in 2022) announced the creation of the American Sunlight Project (ASP), the mission of which is to “(increase) the cost of lies that undermine our democracy” by “mobilizing to ensure that citizens have access to trustworthy sources to inform the choices they make in their daily lives.” Given the importance of issues related to dis- and misinformation in the context of scholarly publishing, I invited Ms. Jankowicz to respond to a series of interview questions; responses came from her and also from Carlos Álvarez-Aranyos, the ASP’s co-founder and Chief Communications Officer.

The Scholarly Kitchen (TSK): For the purposes of ASP’s work, how is the term “disinformation” defined?

Nina Jankowicz (NJ): Disinformation is defined as the use or amplification of false or misleading information with malign intent. This is different from misinformation, which is when someone creates or shares false information without malign intent. For example, someone touting a miracle diet pill in an attempt to get rich quick would be spreading disinformation, whereas your eccentric cousin bringing up his favorite Thanksgiving topic — the staging of the lunar landing — is just amplifying misinformation.

How will the ASP deal with difficult issues in which actual facts are in dispute – will it remain silent on such issues, or will it follow a particular line of strategy in determining what side to take on the factual question?

Carlos Alvarez-Aranyos (CAA): We have no interest in arbitrating truth. Healthy debate is essential, and we will never seek to interfere with it in any way.

I think the answer to your question goes back to the definition of disinformation: It’s lies told with malign intent. That last part distinguishes disinformation from traditional lies, and it separates our work from the referee-type behavior you’re suggesting.

In cases where bad actors are disseminating lies in order to deliver a strategic outcome (such as the fake Biden robocall that went out just prior to the New Hampshire primary, or deepfake videos produced to generate confusion in the midst of a crisis), we will seek to identify and expose the bad actors behind those efforts.

TSK: How is information analyzed at the ASP in order to determine whether it should be flagged as disinformation? What criteria are used, and how are they applied?

NJ: The American Sunlight Project will not be engaging in traditional fact checking or “flagging” of content. Instead, we’re more interested in exposing to the American people how information flows and the deceptive practices that get disinformation into their feeds. We will also work to make primary sources more accessible to Americans who want to rely on truthful information in their daily lives.

TSK: Can a factually true statement constitute disinformation? If so, how do we deal with that?

NJ: The most successful disinformation often has a kernel of truth at its core, or builds on false concepts that have been socially normalized as true. It might take the form of a quotation stripped of context to make it seem like the speaker was saying something they didn’t actually say, the exploitation of deeply held beliefs on divisive issues such as gun rights, or information that builds on an existing widely-held conspiracy theory.

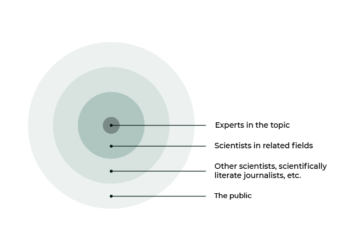

That’s why we at ASP are primarily focused on information flows: By understanding the provenance of information and the ways narratives shift as they jump from anonymous internet fora to fringe news outlets to mainstream news and are then amplified by politicians and influencers, we can expose citizens to a more nuanced view of what they’re consuming, hopefully driving greater understanding.

While those who spread lies for power and profit often benefit from painting the world in black and white, we know it’s actually quite a colorful place. Seeing the entire, colorful picture of our country in all its detail is crucial to a strong democracy, and a big part of that is understanding where the information we’re consuming is coming from.

When I teach my course on “Disinformation and Influence in the Digital Age” at the Syracuse Maxwell School, one of the assignments I give my graduate students early in the course is to track their information consumption for 24 hours. Many roll their eyes at this assignment; they think they have great information consumption habits. Sure, they read widely, but in the Internet age — and particularly the age of mobile news alerts and autoplay — many of us are consuming information quite passively. Most students are shocked at the amount of information they digest through digital osmosis.

By introducing individuals to the concept of more deliberate information consumption — and by educating them about the tools that allow deceptive information practices to flourish, such as targeted advertising and algorithmic amplification — we can help them develop a clearer, more colorful picture of the information environment they inhabit.

TSK: In scholarly publishing, we have to find a balance between filtering out false information and providing a forum for informed views and research results that may contravene majority views or received wisdom. How should we distinguish between disinformation and genuine scientific/scholarly disagreement?

NJ: Scholarly and scientific publishing can and should be a place for lively debate and discussion. But that debate and discussion should not be based on clearly false information, information that is not replicable in randomized controlled trials, or misleading information that is spread with intent to deceive. Scholarly publications now also have to contend with the hallucinations and misstatements of generative artificial intelligence. I do not presume to lecture the scholarly community, but I believe this is a great moment to review the scholarly publishing process and its incentives. The peer review process — when engaged in earnest and with the best of intentions — ought to be a failsafe against the quandaries that scholarly publications are faced with in the digital age.

TSK: You’ve observed that “disinformation knows no political party.” Will ASP hold everyone, across the spectrum of political and social views, to an equal standard of scrutiny?

NJ: Absolutely. I’ve personally called out disinformation coming from the left before, as well as what I feel was a hyperbolic response to Russia’s 2016 election interference. I’ve also called out the current administration for what I perceive as mistakes in its response to disinformation. I believe in an actor-agnostic approach to identifying and countering disinformation, and that means telling hard truths. Even if doing so won’t win us friends in the short term, it will make our democracy stronger in the long run.

TSK: Defending our democracy means, among other things, preserving space for a broad range of views, opinions, and interpretations of reality. In a democracy, there will be a lot of people who think other people’s expressed views constitute disinformation (or at least misinformation). How should we manage the tensions between preserving respectful space for viewpoint diversity and rooting out disinformation?

NJ: One of the things that the internet strips from our discourse is face-to-face interactions. I’ve received a lot of abuse and people have said horrible things to me online because they disagree with me. They likely wouldn’t say these things in person. That doesn’t make online abuse any less horrific, but it reminds us that it becomes more acute because it’s dehumanized.

If you wouldn’t want something said to one of your family members, perhaps you shouldn’t be saying it at all. There is so much room for disagreement without resorting to violent speech or action. I would never wish what I have gone through on those I disagree with, or on purveyors of disinformation. I will defend my right to call them out — but I firmly believe that it should be done respectfully.

Unfortunately, this sort of violent rhetoric has become normalized in our politics. Whenever I interact with members of Congress and other political leaders, I remind them their words have consequences, and that they must set the respectful standard for discourse we hope to see in our country. America is — and must be — better than name-calling and threats.

Discussion

1 Thought on "The American Sunlight Project Wants to Make It More Costly for Bad Actors to Spread Disinformation: How Will They Do That?"

Thanks Rick, excellent, interesting and topical post, this answer below caught my attention, re what scholarly publishers might do, reproducibility and transparency of the whole research body of work, underlying data, code, protocols for the article, are key areas to consider, obviously some discipline specific nuances, but I do believe more is being done by publishers in the area of transparency and reproducibility.

NJ: Scholarly and scientific publishing can and should be a place for lively debate and discussion. But that debate and discussion should not be based on clearly false information, information that is not replicable in randomized controlled trials, or misleading information that is spread with intent to deceive. Scholarly publications now also have to contend with the hallucinations and misstatements of generative artificial intelligence. I do not presume to lecture the scholarly community, but I believe this is a great moment to review the scholarly publishing process and its incentives. The peer review process — when engaged in earnest and with the best of intentions — ought to be a failsafe against the quandaries that scholarly publications are faced with in the digital age.