Mark Twain said, when asked what the limits of copyright should be, “Well, I said, perpetuity, I thought it to last for ever.”

In this post, I want to take some time to consider the role of copyright in the digital era. It is also worth looking at the role of Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) and how its fortunes appear to be rising from the staid organization it was only a few years back. In August of this year, Alice Meadows, fellow chef, presented a fascinating interview with Roy Kaufman, Managing Director of New Ventures at CCC. CCC reported last week that it paid a record $188.7m to rights holders in fiscal 2013, up 5% from 2012. Clearly copyright remains a force in a digital age, one that CCC recognizes, and one that presents a fascinating glimpse at the potential future role of an intermediary such as CCC in stimulating creative efforts.

To really think this through, I spoke with CCC, and some of their thoughts on the future are presented here. I also looked at a fascinating report from the National Academies Press in May 2013, entitled Copyright in the Digital Era: Building Evidence for Policy. This work was prepared by Stephen A. Merrill and William J. Raduchel on behalf of the Board of Science, Technology, and Economic Policy. This report is used as a resource throughout this post.

First, we should understand the history of copyright, and in fact why would should think about copyright at all. I enjoy Jack Bernard’s (Associate General Counsel at the University of Michigan) way of asking us to consider the meaning of copyright:

What is the purpose of U.S. copyright law? The answers are below. Jack Bernard indicates that very few think of (C) as an answer.

A) Reward authors for their creative efforts

B) Provide an economic incentive to write & publish

C) Advance public learning

D) Provide legal remedies for infringement

In other words copyright laws are in place to encourage access, creativity, and expression of ideas – this is important for us to realize in a time when copyright is more likely to be referred in restrictive terms.

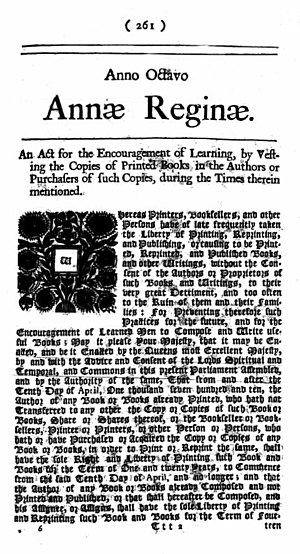

How was copyright law established deep in print publishing’s past? Once upon a time there was the printing press, Guttenberg’s innovation in the second half of the fifteenth century. It was not until 1710 that the English Parliament created copyright laws as we would recognize them today: the ability to grant exclusive rights to an author that are transferable for printing, reprinting, selling, etc. In the US of course, life was more complex, with variations across states, and it was only in 1790 that the US Government enacted the first Copyright Act – in fact this was one of the first acts of the United States Congress. The purpose of copyright is etched into the Constitution in Article 1. §Clause 8.,

To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.

As is the way with early legislative activities, that there was not much detail in these laws. It was up to courts over time to refine exactly what these laws meant to all the stakeholders involved.

As new technologies allowed for new means of authorship, the rapid expansion of publishing, the inclusion of new media such as photographs, music, and movies, so The United States Congress would again and again amend copyright laws, with a new act in 1976 covering reproduction, derivative works, distribution, performance and display. Further amendments have been made more recently to help us in a digital age, and to address the rights of copyright owners to see reward from digital streaming, with protection from piracy over digital networks.

So let’s look at some of the issues we face in considering copyright in a digital age. Technology itself is now embedded into copyright, allowing copyright holders to use innovative tools to prevent piracy, or to select the type of user who may be granted access. But where lays the balance? On the one hand, copyright law enshrines the concept of fair use. On the other hand, how much content may be shared before copyright is infringed? This is where there is much blurring of lines, especially when looking at how digital library holdings are utilized and e-coursepacks are used.

And then, what about open access and copyright law? In some ways, this represents the true red herring in OA discussions. It does not matter who has the copyright, copyright is still a force and all aspects of fair use and the ability to stimulate scholarship remain. It boils down to a business decision by the author, funder, institution and publisher.

Where does CCC come into the picture? For the answer to this question I turn to Roy Kaufman. His view is that the future for CCC can be divined by looking at how CCC was founded back in 1978. This was the period when Congress was going through its lengthy deliberations over what should be in the new copyright act. In the midst of all this comes a new disruptive technology, the photocopier. How would this new technology alter handling copyright issues? And so CCC was born, at the suggestion of Congress, as a central agency for handling copyright requests among content owners and users.

The future for CCC takes them a step further with this philosophy. In a digital age, we see more technology, more ways to atomize content, and more content that may be licensed. The role of an intermediary such as CCC is further cemented in this more complex environment that ironically leads all stakeholders to crave more simplicity in handling licenses. In addition to this, as Roy says, “People will comply with copyright if it is easy to do so, and they are less likely to comply if it is hard.” So, CCC sees its role as enabling the use of copyright. Another view of CCC’s role here is to look at its evolution into developing workflow tools. Dow Jones kicked this off, requesting a product that allowed for external customers to re-use its information content. Essentially this is a workflow tool, which extended into the development of RightsLink as a tool for managing color charges, page charges, and now article processing charges (APCs).

It seems to me as if CCC is heading towards being a data rich organization, like Thomson-Reuters, that could provide authority and metrics around the licenses held and shared – a digital repository that in principle could serve as a measure of an author’s impact on the world. In talking to Roy, while my musings are clearly my own, he does indicate how CCC is working in a Creative Commons environment. While no signed license is required for a CC-BY OA publication, it may be that a corporation who wants to share a large number of copies of an article would rather have a paper trail that authenticates the license. So, while not required, CCC has an option for a corporation requesting rights to an article to request the license itself. This is data, and this data is accumulating in the CCC repository – think how valuable this could be.

In summary, copyright is indelible to the creation and publication of content. There is real value in being able to go to one place to definitively determine the copyright status of something you want to reuse. What we will see going forward is the enabling of tools around licensing data, and simplified workflows.

Watch this space.

Discussion

23 Thoughts on "Copyright in a Digital Era: The Rise and Rise of CCC"

The US Government is working toward making a huge number of journal articles publicly available after an embargo period which the government itself specifies. Are there any copyright restrictions on the use of these documents once they are made available, or does copyright simply vanish? I have not heard of any restrictions. If not then the journals are being seriousy devalued, because they are only selling access for the brief time that the government allows. CCC stands to lose as well.

Moreover, the government is apparently claiming the right to do this with any article written in a researcher’s lifetime that is somehow based on prior research funded by the government. How is this possible? What does “based on” mean in this case?

Surely these are important copyright issues, involving several poorly defined concepts that cry out for clarification. Is there work on this?

My understanding of the OSTP memorandum is that it does not require any specific licensing terms. It does request that efforts be made to encourage “creative reuse” of articles, but there are no demands to remove or change the copyright status of the articles themselves. In fact, the memo requires agencies to, “describe, to the extent feasible, procedures the agency will take to help prevent the unauthorized mass redistribution of scholarly publications.”

Well NIH already provides public access via PMC and they have half of the US Federal basic research budget, so it is the primary precedent for the OSTP non-NIH agencies. What is the copyright status of author manuscripts published by PMC? Is there any formal specification or grant of copyright? What is it’s legal basis?

The OSTP memo language sounds self-contradictory, which would not be surprising as it is a political policy document. Creative reuse versus authorized distribution? Authorized by whom, by the way, the agency or the copyright holder? Nor does it have any legal force that I know of. It is just a staff memo.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/about/copyright/

All of the material available from the PMC site is provided by the respective publishers or authors. Almost all of it is protected by U.S. and/or foreign copyright laws, even though PMC provides free access to it. (See Public Domain Material below, for one exception.) The respective copyright holders retain rights for reproduction, redistribution and reuse. Users of PMC are directly and solely responsible for compliance with copyright restrictions and are expected to adhere to the terms and conditions defined by the copyright holder. Transmission, reproduction, or reuse of protected material, beyond that allowed by the fair use principles of the copyright laws, requires the written permission of the copyright owners. U.S. fair use guidelines are available from the Copyright Office at the Library of Congress.

By creative reuse, they’re really talking about text and data-mining, which can certainly be done without violating copyright.

I know little about this, hence my questions, but I sense a deep confusion. If a PMC article is downloaded 1000 times isn’t that 1000 copies?

In fact the reference to reproduction seems like a throwback to print. If I am a teacher I do not have to copy and hand out a PMC article. I just tell my students to all download it. If I want mass distribution I just broadcast the URL. In this sense the copyright has indeed vanished as soon as the free copy is posted. The Internet is a copy machine.

Not “vanished” because derivative works and commercial reuses still fall under copyright and are not voided by the NIH policy. Also, while it is true that the URL is free to distribute so that anyone can access the articles online, there is no right to print out copies and distribute them freely–a right that is hugely important for OA publishers of monographs, which derive crucial revenue from sales of POD editions. This has been the business model followed by almost all OA monograph publishers so far including National Academies Press, the presses at Michigan and Penn State (which I directed), Knowledge Unlatched, and presumably the new Amherst College Press.

Your basis for the claim about text and data-mining is what?

Very useful, thanks. But the journals are still being devalued because they only sell access for a limited time, after which it becomes free to all. Access, not reproduction, is the journal’s primary product. The core issue is the government’s right to do this and the scope of that right, if it in fact exists?

I hope you will forgive a neophyte for butting in, but ‘by what right?’ caught my attention.

Is it the right of the consumer to demand a new contract? I hope you’ll forgive the substitution of ‘we’ for ‘government’ in this case, when I say that we (through taxes &c) hire scientists to perform a service. The fruits of that service (research papers) are sold to a third party so that we can buy back access. This is not to say that publishers don’t add value; look no further than Mr. Anderson’s excellent list elsewhere on this website for a thorough refutation of that idea. Chief among the values publishers add are peer review, editorial oversight, and from these trust in branding. But these values are difficult to grasp in the face of the sting of paying twice, yes? Especially where the aim of the initial investment is described in such lofty terms as the advancement of human understanding.

In short, I’m not comfortable with the implication that the publishers are Lando Calrisian to the government’s Darth Vader (“This deal is getting worse all the time!”). But I also see that this is a challenge to a distinguished business. Is there space to negotiate a longer embargo? Is there an embargo period that you feel could accurately reflect the value publishers currently bring? Perhaps more importantly, is there a value that publishers can add in the future beyond access to the latest in research that would entice subscribers to remain subscribers, to attract new subscribers? Publishers, it seems, would be in a better position than the government to add value to the available literature than a government database (which I imagine to be as user friendly and as welcoming as the warehouse where they stashed the ark of the covenant).

Sorry to go on. I realize it’s a challenge, and it’s disruptive. But it’s difficult to say it’s wrong. And in challenge lies opportunity. I hate ending on a platitude. But there you go.

Probably worth mentioning that the research paper is not the “fruits” of the labor performed by the researcher (and at times paid for by the taxpayer). The actual research results themselves are the fruit, and despite all the furor over opening access to the articles written about those results, they are usually locked up behind patent paywalls. You’re not paying for an article written about the cure for disease X, you’re paying for the cure for disease X. More on this here:

http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2013/08/06/is-access-to-the-research-paper-the-same-thing-as-access-to-the-research-results/

Exactly. The policy position has been that the government pays for research because the results benefit society. The people pay for progress, not paper. The ownership of the journal articles has never been an issue until now, and a goofy issue it is.

Les, What I question is the government’s claim that they have an ownership interest, a license, in everything I write for the rest of my life that is in any way based on the work I happen to have done for them. I cannot find a legal principle that supports that claim. The government got what it paid for, which is my research plus a report. After that my expressed thoughts are my own, or should be.

You have to go back to the Constitution to understand that, one of the powers that Congress has is the right to create a copyright law. They determine the scope of copyright, exceptions, the public domain etc. Copyright does not just come out of thin air. Congress has the right to create and amend copyright. It is a statute.

I’m assuming that it is all based on this (from Wikipedia):

“A work of the United States government, as defined by United States copyright law, is “a work prepared by an officer or employee of the” U.S. federal government “as part of that person’s official duties.”[1] In general, under section 105 of the Copyright Act,[2] such works are not entitled to domestic copyright protection under U.S. law.”

So, in this case, there is no copyright in this material once it is made available. Feel free to argue about whether you are or are not an officer or employee of the US Federal Government in this context. But I would bet dollars to doughnuts that this is the assumption under which this all applies.

By virtue of its being a revenue-driven organization, the CCC will naturally err on the side of revenue maximization. In other words, the propensity for helping rights holders make overreaching claims is baked in. This was quite evident in CCC’s funding of the claims against Georgia State University.

Thus the need for a countervailing force. Unfortunately, that force has yet to emerge.

You have something against rights? What do you see as overreaching?

Nothing against the legitimate assertion of copyright here. I cited the Georgia State University case as an instance of overreaching. CCC is simply following the nature of revenue-driven organizations which is to err on the side of enhancing revenue. This, naturally, creates a propensity to overreach and exceed the bounds of legitimate copyright assertion. That is, unless there is a counter balance of some sort.

The usual counter balance is the cost of litigation plus its probable lack of success. That is how checks and balances works.There are avenues of redress but they are increasingly difficult, as they should be.

Your opinion on Georgia State is just that. It is an argument, not a proof.

And last I knew all organizations were revenue driven. It is called survival. I personally am revenue driven because I keep getting these pesky bills.

> I personally am revenue driven

so given the chance to be paid an enormous sum of money for an repugnant act, you would do it to get rid of the pesky bills? Clearly not (and I do not believe it for a second). The same can be said of some organisations that place public benefit higher on their priorities than other organisations; it is a matter of degree.

Not sure what you mean to say by emphasizing that the CCC is a “revenue-driven organization” that aims at “revenue maximization.” Are you aware that the CCC is a non-profit organization chartered in the State of New York, and that it is as much mission-driven as revenue-driven, the proof of which lies in the fact that it operates some programs for mission purposes at a loss? (I am a member of CCC’s board of directors.)