Editor’s Note: This post is by Phil Jones, Head of Publisher Outreach for Digital Science. Phill has spent much of his career working on projects that use technology to accelerate scientific discovery.

Earlier this year, I remember sitting in a conference hall, listening to a presentation on discoverability of scholarly content. As I sat there, I noticed the speaker repeatedly referred to ‘students and faculty’. The phrase leapt out at me not because of who the speaker was referring to, but who they left out. I started listening for, and kept hearing, the same turn of phrase in other presentations and at other conferences. When we talk about academics, we talk about students and we talk about faculty, but at almost all institutions, there is a group that sits in between these two, the long-suffering journeymen of academia, who do much of the actual work; the postdoctoral fellows. It occurred to me that as an industry, both publishers and librarians ought to be talking about postdocs a whole lot more. After all, it can be said that this overlooked group are responsible for creating and consuming a significant portion of, if not most published scholarly content.

In 2010, I left a faculty position at Harvard Medical School having recently been promoted after five years as a postdoc. People sometimes ask me why I clung on so long only to bail when I finally got that promotion. I’m not sure quite why, but perhaps my stubborn streak wouldn’t allow me to walk away until I’d beaten the postdoc trap, or at least until I could say that I had. Friends and colleagues continued the postdoc grind: some of them eventually got faculty positions, but many of them, including some of the most talented and dedicated scientists did not, and left academia for posts in the pharmaceutical industry, teaching, consulting, and even publishing. A big part of my personal motivation for starting a career in publishing innovation was the frustration of seeing many of my most gifted colleagues abandon their original ambitions not because of lack of talent or productivity, but because they were not being recognized for the work that they were doing.

Given my experience, I was delighted when a couple of months ago, the STM association asked me to put together a panel of early career researchers for the STM Frankfurt conference on October 7th, the day before the Frankfurt Book Fair. Populating the panel has not been a straightforward process. Finding volunteers to speak was not the hard part. Several of my former peers have their own labs now and access to eager young volunteer postdocs. The sticking point was money; postdocs often scrape through on bare minimum salaries and so few of them can afford a trip to talk to a room full of publishers. Fortunately, with the generous help of Wiley, Elsevier and the STM association themselves; we were able to obtain sponsorship funds to facilitate travel for an international panel of talented young scientists from a range of scientific disciplines.

You might be forgiven for thinking that my passion for postdoc recognition is a personal hobbyhorse, borne out of my frustrations as a late stage dropout from academia. You might wonder why I’m suggesting that postdocs are of particular importance to scholarly publishers and why I’m complaining so vehemently on their behalf. Being a postdoc is tough you might say, but life is tough, and many careers have rites of passage during which aspiring young people must pay their dues. Isn’t being a postdoc just the same as being a junior doctor or clerking at a law firm?

Well, not exactly.

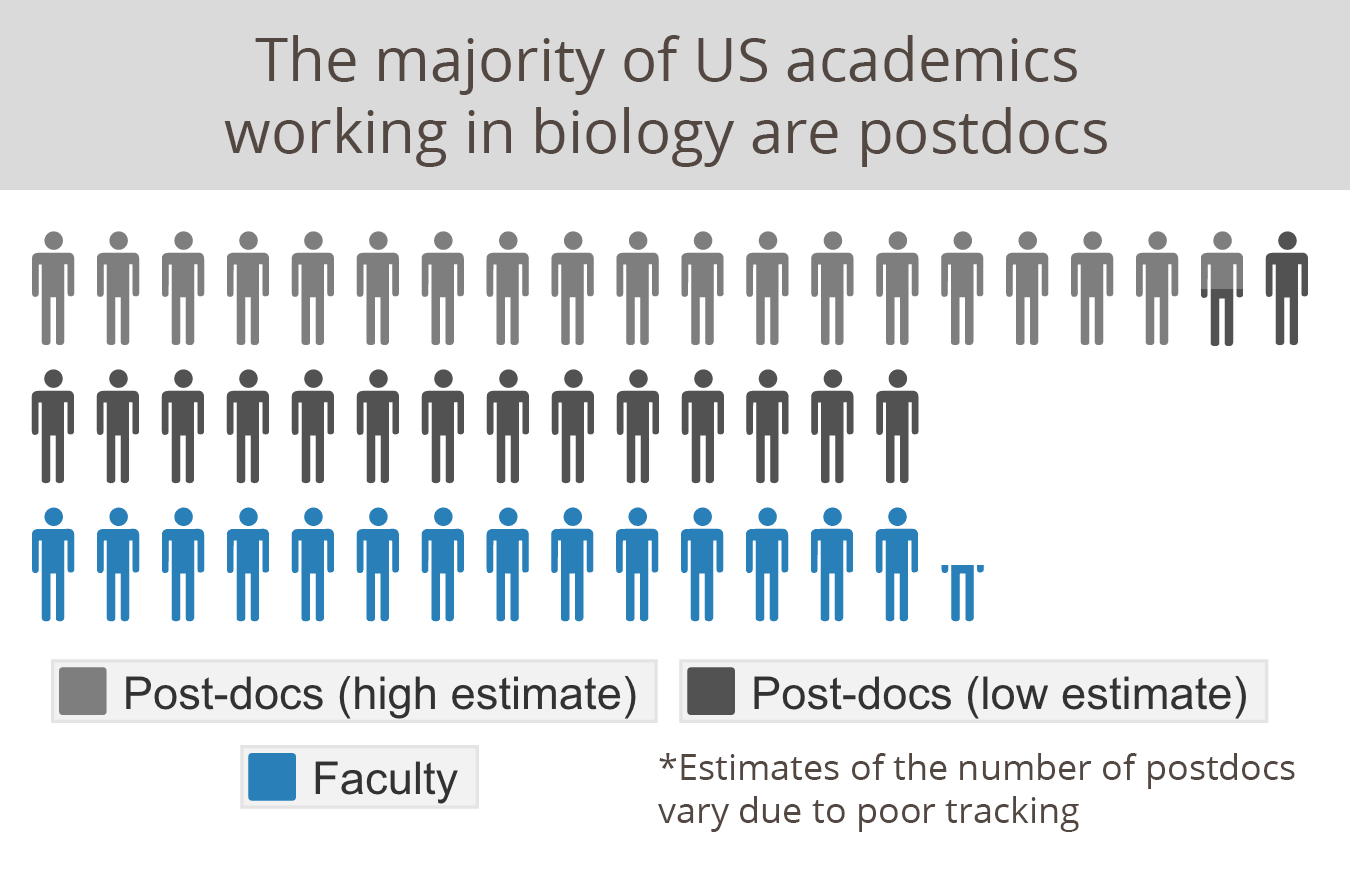

Research on the numbers of postdocs globally is difficult to find, due in part to the fact that neither universities nor funding agencies do a particularly good job of keeping track. However, it is clear that over the past decade, the number of postdocs and the length of time that researchers spend as postdocs have risen sharply. Fueled by what many academics consider to be an over-production of PhDs, and ever-scarcer funding to support full-time faculty positions, the national postdoc association estimate that there are around 90,000 postdocs in the US alone. According to this infographic from ASCB, primarily based on the 2012 NIH workforce report, only 15% of early career stage researchers in Biology ascend to a faculty position within six years of being awarded a PhD, and nearly a third do more than one postdoc. Perhaps the most startling statistic on the infographic is that there are estimated to be between 37 and 68,000 postdocs but only 29,000 University faculty members. Other analyses suggest that for every tenure track position in any field, there are roughly seven postdocs. In other words, postdocs make up the majority of professional academic researchers. It seems to me that if there’s a market that we ought to be thinking about, it’s postdocs.

The days of the postdoc being only a short stop along the way to a tenured post are long gone. Postdocs today are conducting much of the research, designing experiments, running labs, writing articles, participating in peer-review, and even writing grants, often on behalf of the principal investigators for whom they work. All the while, they are trying to build a personal reputation and distinguish themselves from their colleagues and competitors in hopes that they’ll be one of the 20% or so that make it all the way to a tenured position.

Increased competition for faculty jobs coupled with a highly challenging funding environment has significantly changed the nature of career advancement over the last decade or so. Researchers used to have to show that they were competent scientists in order to obtain a tenure track position and then develop an international reputation through published articles, conference talks and grants won, as they advanced through the tenure track process. Today, postdocs are often challenged to demonstrate that they have developed an international reputation just to obtain that initial faculty position. There has emerged a globally competitive marketplace for faculty jobs, with greater requirements for advancement to mid-career than ever before.

Of course, It’s not all doom and gloom. Postdocs represent the professors and scientific leaders of tomorrow and many of them will go on to have highly successful careers. For those at top institutions particularly, in labs with established reputations and solid publication track records, they can use their postdoctoral years as a springboard for their scientific careers, particularly if they have a supportive supervisor. Good supervisors realize and understand the situation that their postdocs face and view it as an obligation to train postdocs in the skills that they need to get a faculty job, such as grantsmanship, research planning, giving talks and writing for publication. Good supervisors also see it as a matter of professional pride to have their postdocs go onto successful careers themselves, and do their best to make sure that postdocs get the credit that they deserve for their intellectual contributions.

However, this training and support is often informal and generally not accredited or even required by universities. As a result many postdocs never receive adequate training, and are never pushed out into the limelight, irrespective of how much they contribute. For those in need of support, there are some national and international organizations like Eurodoc and the national postdoc association in the US, who are fighting for reform through their agenda for change. Still, campaigning for change on a political level is a slow and costly business and many postdocs still feel trapped in positions with no clear path to a permanent position. In the mean time there a real need among postdocs to mange and build their own professional reputations, independently of their supervisors, by showcasing their own personal contributions to science.

With postdocs being in such an unenviable position with apparently so little economic power, it would be easy to assume that they don’t represent an important market segment. Wouldn’t such an undervalued group have very little sway over institutional purchasing decisions? In the past, this would be a strong argument but it has lost its validity in the digital age. Institutions subscribe to the resources that enable academics to do their work effectively. These judgments are made with the support of metrics such as COUNTER and other usage statistics and in some cases, the number of articles published in particular journals by researchers affiliated to that institution. With postdocs making up the majority of working researchers, it’s clear that their reading and authorship choices have a strong impact on publisher revenues. For Open Access journals, the effect is even more direct, with postdoc authors often having the final say on where they publish their articles and therefore, to whom the APC is paid.

A second and perhaps more subtle consideration is the trend in funder mandates that push towards open science and the increasingly diverse measures of value and impact in research evaluation. The most commonly cited example of evolving funder attitudes is the REF in the UK, but the Dutch SEP and Australian ERA are following suit in requiring funding recipients to demonstrate the broader societal impact of their work, which can include activities such as public engagement, policy influence and patents. This movement has been a big driver in the rise of interest in altmetrics at institutions and as a key publishing value-add.

Looking to the future, we’re also beginning to see funder mandates to make underlying data available. It is clear that data publishing and repositories will become increasingly important as data sharing mandates become more common. From a business model point of view, perhaps the most interesting aspect of evolving funder perspectives is hinted at in the very last bullet point of the RCUK Common Principles on Data Policy:

It is appropriate to use public funds to support the management and sharing of publicly-funded research data.

In the same way that Open Access created a new revenue stream in the form of APCs for many publishers, facilitating data sharing represents a similar potential source of revenue.

While, in principle, these trends should affect all researchers, in reality, established investigators will be able to rely on their track records to a much greater extent than those at early career stage. Postdocs, therefore, stand to gain the most from new forms of publishing and managing their scientific reputations in accordance with changes in funder attitudes and values.

As new approaches to scholarly communication emerge, many young scientists are already building and managing their own reputations online. People like Erin McKeirnan (@emckiernan13) and Jon Tennant (@Protohedgehog) use social media and their personal blogs to reach an international audience with their own independently produced content. This approach can be very impactful from a scientific perspective, for example Rosie Redfield’s use of her blog to publish her disproof of NASA’s claims of a bacteria that could metabolize Arsenic. From a career development perspective, ground breaking scientist/blogger Jonathan Eisen claims that the judicious use of social media helped him score several grants (although, as a caveat, Eisen has also said that social media has also had negative impact on occasion). These approaches to personal scientific reputation management are still at a relatively early stage, however there is growing demand for it, and funding sources are being made available for new forms of scholarly communication that support it.

At Digital Science, one of our goals is to support the next generation of researchers through new forms of digital communication. Figshare is a repository that allows researchers to put all their research outputs online and make them citable with a DOI. It is a great example of how we’re helping researchers claim credit for their scientific contributions by enabling them to make available everything from videos to computer programs, to more specialized outputs like astronomy data and chemical structure information. By tying alternate research outputs into traditional publications, we add value to the publishing experience, particularly for authors interested in building and managing their reputations, and enable them to showcase their own personal contributions. Altmetric is another offering that is of value to younger researchers, as well as more established ones. By enabling researchers to monitor their impact in ways broader than just citations, we help them capitalize and demonstrate the external effect of their work, and prove their value to funders, and by extension, institutions for which research funding is an important goal.

Other companies have begun to respond to the new needs of researchers. Earlier this year, I organized a panel at the SSP annual meeting where I invited David Sommer of Kudos to speak. Kudos is a platform to enable researchers to build their own reputations through summaries of their work, video abstracts and other types of new content. There’s also Bitesize Bio, founded by Nick Oswald and based in my new home city of Edinburgh that approaches the same idea from the perspective of a science specific blogging platform. These are just two examples.

In the future, there will likely be more innovation around this type of assisted self-publication. For instance, it may be possible to push content directly from electronic note-books and lab management programs, such as Labguru, to the web, and associate it through meta-data with the peer-reviewed article to which it relates. Researchers will be able to effortlessly participate in open science, prove their value to funders and build their reputations in a way that is accredited, legitimized and promoted by scholarly publishers.

Institutions have their role to play of course. Today, the ways by which early career stage researchers progress to mid-career are often arbitrary with too little control afforded to the postdocs themselves. Progress to faculty level depends too much on being in the right lab at the right time with a sympathetic supervisor, and not enough on the merits of the researcher. The risk here goes beyond simple unfairness; if our current scientific system does a poor job of selecting the most talented to advance, the quality of research and the progress of science will suffer. While publishers can’t control the way that institutions or funders manage their decisions and frankly, have no business doing so, we can support young researchers by providing tools to help them to independently build their personal reputations in line with funder values, thereby leveling the playing field.

At the end of the day, it’s postdocs themselves that we need to take our cue from, and so I’m looking forward to continuing the conversations with the panel of speakers in Frankfurt and learning more about what they need from publishers to be successful. By listening and adapting to the needs of the next generation of researchers, not only will we find the inspiration to develop new products, services and business models, but we’ll also be providing a significant service to science itself.

The panel will be part of the stm frankfurt conference on the 7th of October at 2:45pm, which will be 8:45am Eastern Daylight Time. It won’t be streamed live, unfortunately, but If anybody has any questions for the panelist, please feel free to tweet with the hashtag #stmpostdocs and I’ll post replies in the comment section below.

Discussion

22 Thoughts on "Guest Post: Phill Jones on The Changing Role of the Postdoc and Why Publishers Should Care"

Are these primarily post docs in the biomedical sciences?

My experience was as a postdoc in biology labs and certainly, biologists make up at least the single largest group and possibly most postdocs, which is probably why there is at least some data available. Having said that, I’ve spoked to young researchers from across the sciences and hear similar stories.

In the panel at Frankfurt, we had two Biolgists and a Chemist

I am a fourth year biomedical postdoc. I think postdocs are likely to be key to solve the “peer review crisis”. Currently, I receive maybe only 1 or 2 invitations a year to serve as referee. As far as I can estimate from speaking to other postdocs, this is relatively typical for senior postdocs in my field. I would happily review more papers, and after a decade in science I am probably well-qualified to do so. My impression is that editors prefer faculty members with more experience. I think in many cases senior postdocs can compensate by having more recent hands-on experience, and possibly a greater willingness to spend time reviewing a paper thoroughly.

Thanks Magnus,

Yes, this is a theme that has come up in discussions with the postdocs on the panel. In many cases, editors have relationships with more senior academics, who sometimes then either recommend postdocs or pass the work along.

Perhaps part of the issue, is that it’s not yet fully appreciated just how much postdocs now occupy a central role in research.

Being asked to review papers comes from publishing papers yourself. Once you get in the publishers’ databases as an author, you will get asked to review papers. In my experience, when you first register as an author submitting a paper, the publishers had a section asking whether you would be a reviewer in the future. If you mark yes, then you will get asked.

I reviewed dozens of papers and was never even close to a senior academic.

The concept of “managing” one’s reputation bothers me a bit. Reputation is the judgement of others. If you mean self promotion that can easily backfire. Also, are you claiming that “…our current scientific system does a poor job of selecting the most talented to advance…”?

You seem to be inviting postdocs to throw themselves into a lot of what are really just experiments.

Hi David,

I think we all manage our reputations, don’t we? Presenting ourselves in a positive light is not only something that we have every right to do, but is also absolutely necessary. One of the problems that postdocs face is that by default, their supervisors are assumed to be the intellectual driving force behind the work, and it takes a positive effort by the supervisor to push the postdoc into the limelight. The problem is that this creates a significant perverse incentive for supervisors, particularly for ones who have not themselves achieved faculty. I know a number of very talented scientists who never managed to get faculty posts, purely because they were never recognized by the academic community as being the originators of their own ideas.

Rather than relying on a supervisor, to promote their postdocs to the scientific community, I believe that it would be fairer to enable them to do so themselves. I’m not convinced that using twitter and blogs is the answer here, rather I think that we as publishers need to provide tools that allow researchers to expose more of their personal contributions to science, whether that be data sets, videos of techniques, or their personal perspectives. Rather than forcing postdocs to experiment with these approaches, it’s better if publishers, institutions and funders work together to legitimize new types of research output, as we have done with altmetrics and are beginning to do with data publication.

Yes, I believe that our current system could do a better job of selecting the most talented to advance. Not just for this reason, but for others as well. For instance, there is a growing concern that grant funding agencies are being increasingly conservative when awarding grants. The end result being to discourage the type of scientists who want to do truly innovative work, which by its nature is higher risk. Here’s a blog from NPR that discusses that point.

http://www.npr.org/blogs/health/2014/09/09/345289127/when-scientists-give-up

I must post an erratum to my previous comment.

I meant ‘supervisors that have not yet achieved tenure’, rather than faculty.

Sorry about that.

Phill, my first point was that the concept of managing one’s reputation implies a degree of control that does not exist. Certainly we all try to influence our reputations, and that is one reason I comment here in the Kitchen, but that is not management.

More broadly I am skeptical about the program you describe because it assumes a new system of evaluation that I have no confidence will come to be. Getting post docs to run off in all sorts of new directions may not be good advice, and the same for publishers. So I advise caution here.

As for the selection process, things can always be better but that does not make them poor. I am always skeptical of claims that existing, wide spread and time tested systems of procedures do not work, especially when these systems are run by very smart people. Unlike some others, I do not believe that the system of science is broken.

I didn’t invent the term ‘reputation management’. Perhaps it’s a misnomer, I’m not sure, but either way, that’s a semantic argument, rather than a logical one, and doesn’t have anything to do with the arguments expressed above.

I wouldn’t suggest that postdocs, or publishers run off in all sorts of direction at all, and I didn’t do so in my post. In fact, I clearly state that reliance on current tools, like blogs and twitter, may not suit all postdocs because they require a lot of media savvy on the part the researcher. It is also true that the effective use of these techniques requires a lot of time and effort. What I suggest is that publishers should take a good look at the communication needs of the majority of their users and innovate to meet those specific needs. I go on to identify data publication as being the specific direction that I think we should explore, because, as I said in my post, it’s an emerging trend in funder mandates.

I agree that science is not broken. That’s far too strong a statement and not something that I would ever say. Having said that, it’s misleading to say that the current selection process is time tested. Like everything, it is constantly evolving, and the conditions under which is operates are also in flux. We are in an unprecedented time in science, with a greater number of people at the postdoc stage than ever before, and far greater competition for jobs, promotions and grants. I believe that the pressures that researchers face, particularly young researchers, have evolved to the point where they are damaging the progress of science. That’s a very different statement to saying that science is broken.

How does competition damage scientific progress? Do you think that high journal rejection rates damage progress? Competition is often thought of as a way to find excellence. Of course it is not particularly pleasant.

Competitive environments have high attrition rates, but a high attrition rate doesn’t necessarily mean that effective competition is taking place. For competition to be effective, the way in which we measure people has to align with the qualities that are needed for success at subsequent levels. To use an absurd analogy, if we chose who would represent us in the Olympics based purely on their heights, that would allow us to be highly selective, but we wouldn’t be selecting the best people.

In my argument above, I describe a situation where we have a high attrition rate but don’t have entirely effective competition. What I think is going on, is that the ability and willingness of a postdocs supervisor to promote them to the academic community is a more important factor than how good a scientist they are.

High journal rejection rates are a completely unrelated issue. There are others (EG Randy Schekman http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/dec/09/how-journals-nature-science-cell-damage-science) who have made analogous arguments concerning distorted selection criterion, but I personally haven’t done enough research to comment confidently on it.

Reblogged this on Microbiology, Ecology, Metagenomics and commented:

Really insightful article about the state of the post doc. Lots to think about as I transition into this huge pool of scientific professionals. I’m glad that discussions such as this are taking place.

Phill, on reflection I think that if you narrow your focus to scholarly societies then you have a viable argument. Helping young researchers advance their careers is a big part of a society’s mission. We have discussed here before how communication can do that, which seems to be what you are after.

It may well be that societies are best placed to add value here. After all, as Angela Cochran said, in the recent SSP educational seminar in Washington that she, Rick Anderson and I gave, ‘the one solid competitive advantage that societies have over commercial publishers is access to practitioners’. There may well be creative things that societies can do to help young researchers in particular communicate their ideas particular communities more effectively.

One thing worth taking note of is that societies are struggling to maintain membership numbers, particularly among postdocs. As one of the postdocs said during the Q+A, the value of membership is not clear to many young people. It’s interesting to note that, meanwhile, postdoc associations, which are cross-disciplinary, but focused on that one career stage, are steadily growing in membership and influence, but that’s a whole other blog posting.

I wouldn’t say that the arguments above only apply to societies, though. At the core of my argument, I’m simply saying that publishers should pay close attention to the needs of their users in order to be able to provide those users with value. To me, that basic principle seems unarguable.

I hesitate to argue with the unarguable, but it is not clear to me that a publisher’s concern for its users should include the latter’s career advancement. If a central value of journals is the ranking of papers then where the authors are in their careers probably should not be a consideration. If publishers were also to concern themselves with advancement there might be a potential conflict of interest. But perhaps I am stretching the point.

Thanks Phil – the session at Frankfurt was one of the highlights of the STM meeting. As one of the postdocs there noted (actually I think it was someone in the Twitter stream), it’s amazing how many folks in the audience – including me – had no idea about the challenges postdocs face and the career environment in which they work.

Thanks for the kind words, Ann.

I’m glad that we succeeded in shining a spotlight on the issue.

I hope that we’re just at the beginning of the conversation. As an industry, I think that we need to get a better handle on the needs of postdocs, because they are primary customers, and innovate to meet their needs. Publishers that do rise to the challenge stand to gain a lot, as they will make themselves more relevant and be able to point to greater added value.

This is a great article that highlights a problem in science which extends far beyond publishing. As a lab head, I run into institutional obstacles to promoting the careers of my postdocs. For example, many University programs will not allow postdocs to officially supervise postgraduate students although the realistically do much of the supervision in labs without getting credit for it. Without a mentor willing to argue for them, many postdocs to enormous amounts of work for no official “credit” e.g. something that can go on a c.v. to help them get a job.