Gentle reader, who among us does not fondly recall those halcyon days of childhood spent with your nose held close to the paper, nostrils flaring, attempting to capture every whiff of the chemically induced aroma produced by dragging your fingernails across the surface of a magical scratch n’ sniff sticker? Memories of those artificial smells (“Berry Good” anyone?) are stored permanently in my gray matter (adjacent, no doubt, to the memories of scented markers and the effervescent delights of Shasta) just waiting to be released by a madeleine scented scratch n’ sniff.

That was augmented reality on a sticker in the late 1970s (at least it was the legal form of augmented reality on a sticker). After a long hiatus, augmented reality stickers are back—only this time they have no memorable scents or cartoon characters. But what they do have is equally delectable and never goes out of style: data.

The New York Times reported earlier this week that Google is shipping out stickers with QR Codes (sophisticated bar codes that are easily recognized by cameras) that can be affixed to physical objects (e.g. storefront windows). A cell phone with a camera, a Web browser, and the right software can then read the sticker and link, via the mobile Web, to a new “places page” in Google Maps which aggregates information about that location (e.g. reviews, contact information, maps, coupons, the Web site associated with that object). Google is promoting this new feature by highlighting 100,000 “Favorite Places.” These are businesses or other locations that Google has determined (no doubt via some mysterious Googley algorithm) are of particular interest. Over the next few weeks they will be sending out stickers with QR Codes to these locations (I was happy to see my favorite Chicago restaurant made the list!).

The technology is not new—it has been widely used in Japan for some time and, as the Times reports, most cell phones in that country ship with QR Code-reading software pre-installed. However, it has not been widely used in the US for a variety of reasons.

The idea of connecting physical objects to online data about those objects is a very good one with a myriad of applications. It should be noted, however, that the technology already exists to accomplish much the same thing without the need for stickers.

Current generation smart phones, including the iPhone 3Gs and Motorola’s Droid, contain all the technology necessary to connect the Web and the physical world—minus the stickers. These key ingredients are:

- A camera

- A GPS system

- A compass

- A mobile data connection to the Web

- A display and a mobile Web browser

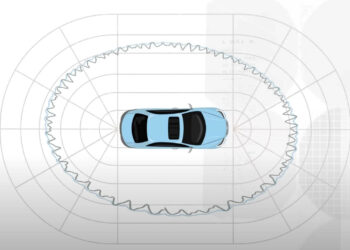

Any mobile device with these five technologies—and the right software—can retrieve information about the physical world just by pointing at a nearby object. The GPS system knows where you are, the compass knows what direction you are facing, and the camera knows what you are aiming at. The mobile data connection can then retrieve information based on these coordinates and display it on your device—no stickers required.

The iPhone application Layar is already doing exactly this (albeit with an emphasis on social interactions). While the business applications (advertising, promotions, etc.) are numerous, what is perhaps less obvious—but far more interesting in my humble opinion—are the potential for scientific and scholarly applications.

A researcher in the field could, for example, point her mobile device at a rock formation, an archeological dig, an ancient tree, or any other natural or man-made object. The device could then retrieve all data gathered about that object or on that site. The researcher could then make additional observations or recordings and upload them to the Web from the field in such a way that they are linked to the record for that location. Moreover, all object- or location-specific data already collected and published in scientific journals and books can be extracted and linked to the relevant coordinates. Instead of performing a complex literature search, imagine simply pointing your mobile device at an object and retrieving all data ever collected about that object.

There are some advantages to using Google’s sticker approach, however. At least until standards emerge, geo-tagged data would need to be indexed by a universal application (or, ideally, an indexing platform with an developer API)—think Layar for science (a similar problem exists with regard to leaving comments on the Web—your Facebook comments don’t show up on My Space and vice versa). This platform would effectively serve as a “map” that connects data to geographical coordinates. Google’s stickers avoid this problem as they simply point to a URL on the Web (which leads me to wonder whether it would be faster to simply type the name of the location into the Google Maps app on my phone…). You do need a QR Code reader (Google lists a number of them here), however, to translate the code to a URL—as well as a device with a camera, a mobile Web connection, and a Web browser.

The sticker system also can provide some level of control over the data associated with an object. The sticker points to a specific collection of data. A store owner, for example, will naturally prefer to control what information is associated with his or her business location (and if the store owner doesn’t like Google’s data collection, she can create her own QR Code sticker, using a code generator such as Kaywa, that points directly to a different URL). There are advantages to the end user as well. Imagine that, next to a painting in a museum there was a sticker with a QR Code. Upon pointing your cell phone at it, a description of the painting, complete with an audio recording, appeared on your phone—in every major language. The user, in this case, is brought directly to the relevant information—something that would be very difficult without such a specific pointer. Using the stickerless approach, one would find all the information various others have tagged at that location—which might include useful information but also might include a lot of information outside of the concise description you are looking for. While the museum curator could participate by posting the same URL as that which would be accessed via the sticker, it would take an extra step or two to get there.

Still, there are many instances where a sticker is not practical. There are historic and natural objects on which placing a sticker would be inappropriate, impractical, or offensive. It would not be practical to place a sticker on a tree on which someone has taken a core ring sample, a rock formation, or a historic artifact. In these instances, a stickerless approach to augmented reality is preferable.

Additionally, the two approaches are not mutually exclusive. A restaurant owner could use a Google QR Code sticker to direct patrons to that restaurant’s places page (or a non-Google QR sticker to direct patrons to the restaurant’s Web site). At the same time, patrons can use the stickerless approach to leave reviews (much like you can now use SideWiki to leave comments on any Web site), pictures, or other notes.

The logical question follows: when will Google announce a scented QR Code sticker? Google Grape perhaps?

Related articles by Zemanta

- Putting a Bar Code on Places, Not Just Products (bits.blogs.nytimes.com)

- The web meets world: Google favourite places, Sixth sense and augmented reality (trak.in)

Discussion

5 Thoughts on "Get a Whiff of Google’s Augmented Reality Stickers"

Hey, some of us used to sniff magic markers for an entirely different reason. I guess that tells you something about the state of my brain.

Esquire Magazine recently put out an “augmented reality” issue and I have to say I felt like a bit of a dolt holding a magazine up to a camera in order to watch a video on a computer. I kept asking myself, couldn’t I just see this content on a website without all the extra nonsense?

Hang on, OK, just needed to put the cap back on the glue bottle there… where were we?

I agree that there is still a lot gimmickry in augmented reality applications at this point. For those with smart phones, it seems like simply typing a location into Google Maps is going to be just as fast as taking a picture of a sticker. Still, I think the general concept of linking physical locations to data about those locations is a solid one and as the technology improves it will eventually become a seamless experience we don’t think twice about. “What do you mean Grandpa? There was a time when the restaurant menu didn’t simply appear in your visual cortex? How did you know what to order?”

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=26d8d762-be71-40d9-bb39-4e0cc49bfd9b)