- Image by fabi_k via Flickr

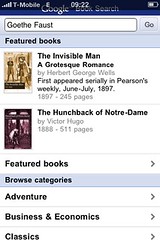

When my company added six million Google Book Search and Google News Archive links to two of its databases last month, I learned a few things about some puzzling disparities in Google’s treatment of scanned public-domain works.

The two databases — 19th Century Masterfile (NCM) and Public Documents Masterfile (PDM) — are discovery aids that link to many millions of documents, nearly all of which are in the public domain. By adding links to the locations of several millions of these on Google sites, we were able to discern, very clearly, differences in Google’s treatment of 19th century historical and literary materials versus scanned government documents.

Click through a bibliographic record to a 19th century item, and you will be able to download the complete document in PDF or Mobipocket formats about 90% of the time. By contrast, click on a bibliographic record linking to a government document, and you will be met in most cases with either no preview, a snippet view, or a limited view. The full-text seems to be available only 10-20% of the time.

I have been asking around about this and have been the beneficiary of any number of theories, but have not been able to get any real clarity as to why this discrepancy exists.

The same thing happens when the documents are viewed through a university’s system. When downloading a 19th century document, a scanned version of ‘An Introduction to Greek and Latin Etymology’ from the University of Michigan library, I was struck by the wording of the introduction that Google includes at the front of each of their scans, as follows:

Usage Guidelines

Google is proud to partner with libraries to digitize public domain materials and make them widely accessible. Public domain books belong to the public and we are merely their custodians. Nevertheless, this work is expensive, so in order to keep providing this resource, we have taken steps to prevent abuse by commercial parties, including placing technical restrictions on automated querying.

We also ask that you:

- Make non-commercial use of the files. We designed Google Book Search for use by individuals, and we request that you use these files for personal, non-commercial purposes.

- Refrain from automated querying. Do not send automated queries of any sort to Google’s system: If you are conducting research on machine translation, optical character recognition or other areas where access to a large amount of text is helpful, please contact us. We encourage the use of public domain materials for these purposes and may be able to help.

- Maintain attribution. The Google “watermark” you see on each file is essential for informing people about this project and helping them find additional materials through Google Book Search. Please do not remove it.

- Keep it legal. Whatever your use, remember that you are responsible for ensuring that what you are doing is legal. Do not assume that just because we believe a book is in the public domain for users in the United States, that the work is also in the public domain for users in other countries. Whether a book is still in copyright varies from country to country, and we can’t offer guidance on whether any specific use of any specific book is allowed. Please do not assume that a book’s appearance in Google Book Search means it can be used in any manner anywhere in the world. Copyright infringement liability can be quite severe.

Immediately, I am struck by the apparently contradictory nature of the message. Notice the phraseology — these are “Usage Guidelines” versus “Terms of Use.” Google asks but does not require. While re-stating that these documents are in the public domain, Google requests that these be used by individuals only, not by organizations, or for commercial purposes. The justification for these requests is the cost of the scanning process which, one can only assume, promises some ultimate commercial benefit to Google.

Google (or their lawyers) seem uncertain about the rights that they have to public domain scans. However, my interpretation is that they are clear about their desire to restrict use by other commercial entities or non-commercial organizations.

Without further information from the source, it’s difficult to know why access to government documents is currently noticeably restricted, in contradiction with the broad availability of 19th century materials. One is also left to wonder whether Google believes that they have any legal grounds for their “Usage Guidelines,” which seem to defy the very nature of public access.

Meanwhile, it seems Microsoft has plans of its own involving public domain materials. An article in Sunday’s Times Online announced that 65,000 19th century works of fiction from the British Library’s collection will be made available for free public downloads this spring . Cited as, “the latest move in the mounting online battle over the future of books,” one wonders if the British Library’s Microsoft-backed project may be the first in a series of initiatives aimed at reducing Google’s stranglehold on public-access materials.

Given how confused Google appears to be about what “public access” means, some competition in this area might be a good idea.

Discussion

8 Thoughts on "Are Google and Microsoft Squaring Off Over Public Domain Works?"

Yes, I have found it particularly annoying that GBS doesn’t give access to non-copyright US government texts. The arguments seem bonkers; it’s hard to imagine they don’t understand that part of the US copyright system!

Access to government information has been a concern in the library community almost from the very first announcement that many of our leading libraries would be working with Google to digitize their collection. For the most part librarians, particularly those who specialize in government information, have had their concerns and trepidations dismissed. However, there is good reason, based on experience, to be concerned about a single company – even one that promise to do no evil – serving as the primary and possibly the only source for much of this publicly created, tax-payer produced information. It is not unlike what happened with access to legal information which is owned and distributed primarily by two companies (both foreign owned – but that is another matter).

Readers may be interested in the discussion around this aspect of Google’s scanning efforts on the website of the American Library Association – http://www.law.umaryland.edu/marshall/ .

Thanks Alix for turning your attention to this.

I am an independent scholar. I use Google Books and other databases, including JSTOR, EEBO and various databases maintained by Gale Research.

My reply does not speak to the direct issue of government documents, but rather to the broader issue of the use of contract law by private companies to use contract law to circumvent the copyright law which allows for the existence of texts outside of copyright — “public domain” texts.

To one extent or another, the claim is made that through ones use of the database that one agrees to restrictions on the use of the material even when there is no dispute that the underlying material is in the public domain.

I fully agree with your reading of Google’s “usage guidelines.” I also think it is a clear statement by its lawyers that they cannot, in fact, assert any control over the files. However, as I mention, below, it seems that they are finding ways to effectively limit ones use of their files by using contract law to control what certain printers are able to print.

1. Regarding Google, as your post points out, Google “asks” us to refrain from making commercial use of its PDF. As the post points out, asking does not seem to be the same as actually making the claim that commercial use of the PDF, i.e. offering the title for sale via an on demand printer is prohibited.

2. Google is, however, making efforts to make just such a use impossible. For example, I was told today by the owner of an Esspresso Book Machine that while Google has licensed its public domain books (or at least nearly two million of them) to on demand book printers who own the Espresso Book Machine (a new product effectively making its commercial debut this year, in 2010) this license carries restrictions. For a nominal fee, the license provides for printing public domain books from Google’s archive (with covers provided by Google) as long as the book has 500 or fewer pages.

However, I was told that the license also states that one cannot add material to the book, cannot, for example, add an introduction. As part of the license the owner of the on demand book printer is also prohibited from printing PDFs of Google Books that have been provided by anyone else. This means one cannot print a PDF on the Espresso Book Machine one has downloaded from Google. It also means one cannot alter a work by, for example, adding an introduction. It also means one cannot print any book over 500 pages (the limit imposed by the Espresso Book technology) by breaking a 900 page book into two volumes. [Note: I have not checked this with Google. As I said, this information is based on a conversation with the manager of an Espresso Book Machine.]

3. With regards Google, and all of the databases offering PDFs with restrictions, I think one must differentiate between the PDF and the text. Is Google making any claim to control of the words within the PDF? I think not.

4. Print publishers of public domain texts are always careful to make clear that the only thing that is copyright is the introduction to the text, or other material added by the publisher, but not the text itself.

5. Google specifically refers to “non-commercial use of the file.” The PDF is the file. On each book’s web page Google offers an (often poor) OCR version of the same text. While they do not offer this as a single file, a single file could be pieced together from what Google does offer. Google does not seem to make a claim regarding its OCR version of the text.

6. One implication of a text being in the public domain is that one is free to copy the text and use it for commercial purposes. One is free to check a public domain book out of a library, scan it, and then publish it. One is thus presumably free to print out a Google PDF, scan it, and then use it as one would wish, including publish it.

7. One is free to type out the text of a pubic domain book and re-set the type and publish the work. One can re-type a Google text and then it is free of any restrictions. Or, if the Google scan is good enough, one could print out their PDF and OCR that to obtain the text.

8.Google’s scan has a “water mark” that they placed there and that they say must not be removed as it is, in effect, the mark of their claim to ownership of the PDF. While a copyrighted text will, eventually, go out of copyright, and as government documents are never copyrighted, Google’s claim (and those of the owners of other databases as well) seems to be a claim with no termination clause. Even awful crimes have statutes of limitations. Can these corporate claims of control really apply for forever?

Google does not place a copyright notice on the PDF. No copy of the scanned text has been registered with the US copyright office, nor has the PDF been deposited at the US Library of Congress. That Google has put money into the project of scanning books is their business, both in the sense, literally, of their business and also in the figurative sense. In a sense, this is the essence of Google’s asking for control of the PDF’s they make available, and it is the basis for all of the claims made by the databases that make claims (all do not). In essence, the claim is, we spent money scanning texts (or in the case of Gale Research for many of their texts they spent money scanning microfilm), and we spend money making these texts available to you online and therefore we have a right to control their use.

9. Public domain images in museums are controlled by museums through their control of copyrighted reproductions of the images. The Mona Lisa is in the public domain. If you walk into the Louvre and take its picture you then control that image in ones camera. The image in ones camera is a piece of intellectual property that is protected by copyright law. Thus, museums go to great lengths to prohibit photography altogether, or photography that would be of a quality that would enable one to publish the image, hence the universal prohibition of taking photographs in museums with a tripod. Google does not seem, though, to make the claim that their PDF of the original public domain work constitutes a new copyrightable product. This cannot be said of all the other database owners.

10. JSTOR seems to take one of the more extreme views of its ownership rights. Here is what JSTOR says on its “wrapper” page to the PDF of an article published in 1868. [The US law that protects the rights of software producers mentions the use of a “wrapper”, something that is in front of whatever it is one is trying to protect and must, ideally, be clicked through to get to the product. Hence, all the “I accept” buttons that one must get through to get to software. Google’s front page to the PDF is its “wrapper” in a legal sense, as is JSTORs statement attached to each of its downloaded PDF files that, “Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR’s Terms and Conditions of Use available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR’s Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.”

Not only is a professor prohibited from printing out 12, much less 150 copies of an article, even if the underlying article is in the public domain and thus if the professor had a copy of the original journal the copies would be perfectly legal, but JSTOR seems to make claims over the actual words.

In the case of the wrapper I am quoting here, JSTOR seems to claim control over the “content” of a PDF of a text that was first published in the 19th century and is thus without doubt in the public domain.

11. In conclusion, it is my sense that few, if any, of the claims controlling the material in these databases have been tested in the courts. I hope that they are tested, and that the public domain wins. It is not just a mattter of attempting to privatize government documents, it is really an attempt to privatize as much of the the public domain as they can manage to privatize, either legally, or through intimidating langauge in legal-sounding “wrappers.”

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=199a16a9-a45b-46ff-ae6a-94cd7e314168)