Some scholars — including Clay Christensen, author of “The Innovator’s Dilemma” and “The Innovator’s Solution” — argue persuasively that the disruption necessary to create viable innovations must come from outside an industry’s traditional ecosystem.

This propensity for outsiders to succeed where insiders fail was elaborated upon recently in an interview with Soomo Publishing’s CEO David Lindrum:

Christensen helped us understand why, in 15 years of trying, we failed to get traditional publishers to build these [new] kinds of resources. . . . Everything in traditional publishing is built around the book, from how the market is analyzed, to the range of features considered and the process of product creation all the way down to how the rep learns a product and makes a call. Every process, metric, and assumption is built around print. . . . [I]f Christensen’s model from “Innovator’s Dilemma” holds up in this market, the new products must come from outsider organizations and will flourish first in fields that traditional publishers see as low-margin and undesirable.

Publishers, who often struggle with innovation and experimentation, might benefit from roadmaps for publishing innovation which encompass concept development, business modeling, market readiness, and audience targeting. For example, David Wojick and I recently collaborated on an article recently, “Reference Content for Mobile Devices: Free the Facts from the Format,” that steps through the initial challenges of transitioning content from websites to mobile devices.

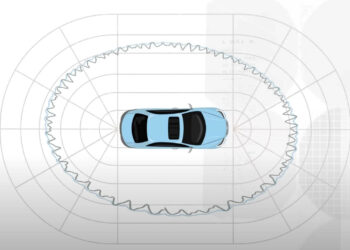

After translating theory to viable business models, the next elephant in the room is consumer readiness. A body of literature has been produced since the 1950s about the technology adoption curve. The diffusion of innovations theory, summarized below, was published by Everett Rogers in 1962. From Wikipedia:

Technology adoption typically occurs in an S curve . . . [d]iffusion of innovations theory, pioneered by Everett Rogers, posits that people have different levels of readiness for adopting innovations and that the characteristics of a product affect overall adoption. Rogers classified individuals into five groups: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. In terms of the S curve, innovators occupy 2.5%, early adopters 13.5%, early majority 34%, late majority 34%, and laggards 16%.

Consider the recent tipping point for e-books. According to the diffusion of innovations theory, the market for e-books is transitioning from early adopters to early majority. How long have we been waiting for this to hit?

Many in our industry recall visiting the well-funded NetLibrary campus in Denver during the late 1990s, followed by the company’s crash and subsequent reboots under new owners. Competitors — like ebrary, EookLibrary, and Knovel — entered the market around 2004 and engaged the innovators and early adopters in our community. But, it wasn’t until 2009-2010 that e-books gained a significant measure of commercial traction. We’re now seeing the acquisitions and consolidations that denote a maturing market, ushered in by Amazon, Apple, and Google.

Hybrid cars were viable before consumers were ready for them. Text messaging emerged in the early 1990s and has taken decades to become “state of the art.” Patron-driven access (PDA) models have been available for several years but have only now entered our mainstream conversation.

Trends and ideas spark around us all the time. Some gain early acceptance, seemingly level off, and then burst on to the mainstream scene years later. Having insight into innovation adoption theories will help us gauge how to best work market levers in order to establish new products and win over larger markets.

Randy Elrod, an artist and author, writes about three types of audience influencers and their impact on innovation adoption in “How to Diffuse Ideas and Influence People:”

(1) Opinion leadership is the degree to which an individual is able to influence informally other individual’s attitudes or overt behavior in a desired way with relative frequency. (2) A change agent is an individual who attempts to influence client’s innovation-decisions in a direction that is deemed desirable by a change agency. (3) An aide is a less than fully professional change agent who intensively contacts clients to influence their innovation-decisions.

Generally, the fastest rate adoption of an innovation results from influencing the innovative influencers’ decisions. As Don Henley of the band Eagles fame once stated during an interview when asked how it feels to be so famous and have his songs permeate society, he replied, “It’s not the fame, it’s the ripple effect I’m hoping for”.

It’s precisely this ripple effect we are seeking through our efforts to re-invent the digital publishing business. We need to achieve substantial commercial success to offset the loss of formerly stable revenue streams. We can give ourselves advantages by acquiring new skills that help us — plan for distinct scenarios, take the temperature of the marketplace, renovate our ecosystems, and prime our audiences for new offerings.

Early evangelism and seeding will help us win the loyalty of early adopters and influencers who will, in turn, lobby the masses to adopt new products. And yet, planning also requires recognition that these early groups are strictly a means to an end, not the end itself. Our target is the majority — perhaps not the commercial mainstream, but an audience with enough critical mass to allow our innovations to take hold and endure.

Discussion

3 Thoughts on "Innovation & Longevity in Digital Publishing: Surfing the S-Curve"

Diffusion is fastest within communities, so creating new communities is a way to speed it up. I have a research report on this, in the context of scientific difusion. Changing the contact rate accelerates diffusion.

http://www.osti.gov/innovation/research/diffusion/epicasediscussion_lb2.pdf