As 2011 recedes in the rearview mirror, it’s a chance to reflect on the best books read during 2011. Now, this is not a “best books of 2011” list, but a list of the best books the Chefs read during 2011 — the books might be classics, a few years old, or brand new. This is one of the great things about books in all forms — they endure, invite visitation and revisitation, and beckon with ideas.

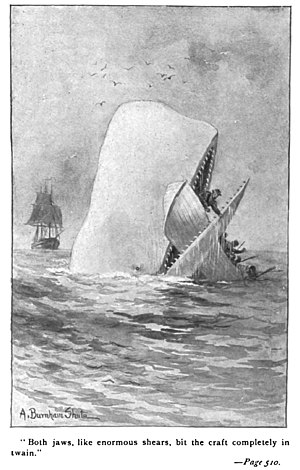

Joe Esposito: As people who do surveys know, how you ask a question can influence the answer you get. The question was, What is the best book you read this year? That’s best book, not favorite. I happened to reread “Moby-Dick” this year, and though I read many good books, it’s hard to top “Moby-Dick.” “Moby” goes on a very short list with Fielding, Dickens, Eliot, Tolstoy, Henry James — Henry James! — Proust, and Joyce, and if you are a hipster, you might throw in Pynchon. But in a year when you picked up “Moby-Dick,” it’s a foregone conclusion what will be cited as the best. This was my third time through “Moby-Dick.” I decided to pick it up again when I saw it referenced in a TV commercial for the RIM Playbook tablet. The Playbook is history now, but in the commercial, Moby’s flukes were used to show off the video display. What is apparent to me is that “Moby-Dick” is more icon than book, more referred to than read. How many copies of “Moby-Dick” can your flash drive hold? Why did Bob Dylan sing of Captain Ahab and not, say, the skipper on “Gilligan’s Island”? This is not a book you recommend — though it may be a book you assign. It’s a legend: little read and little understood. The truly strange thing is that even to embark on reading it seems like Ahab’s quest. Somehow, the book and the whale have come together. Such is literature, such is myth.

Kent Anderson: The book that had the greatest impact for me during 2011 was “Boomerang,” by Michael Lewis. In his typical manner, Lewis makes the arcane approachable and understandable by boiling it down well — in this case, to stories about what people will do when left alone in the dark with a pile of money. Because it’s so revealing of national characters, those around me know I’ll spontaneously relate anecdotes from this book at the drop of a hat — how women in Iceland had to take over the country from their fishermen qua financiers; how the Greeks see government as a wetnurse; and how Americans have become obsessed with getting something for nothing. The financial crises facing Western democracies continue to dog us precisely because national cultures are hard to change, and Lewis’ stories from some of the key countries reveal how the related but particular failures of regulation, reason, and restraint have gotten us into this mess. Each country’s failures are its own — Iceland’s failures of regulation, reason, and restraint were very different from Greece’s, Ireland’s, or the United States’. Many of the essays were published in Vanity Fair before being put into book form, but I don’t read Vanity Fair, many were updated, and the stories and prose will still be compelling years from now, I feel. From the Occupy movement to our political systems, this book resonates with the present day unlike any other I’ve read this year.

David Crotty: The best book I read this year was William Gibson’s “Zero History,” which actually came out in 2010. It is the third volume in a somewhat loosely connected trilogy (the other books being 2003’s “Pattern Recognition” and 2007’s “Spook Country“). While Gibson is perhaps best known for his influential early science fiction novels (“Neuromancer” was instrumental in creating the “cyberpunk” genre and coined the term “cyberspace”), these latest novels are a different breed. Set in the modern day, they are superb examples of Gibson’s oft-quoted statement that, “The future is already here – it’s just not evenly distributed.” His characters are just a few steps ahead of the rest of us, and the books have already proven prescient (“Spook Country”‘s “locative art” became a mainstream reality as developers created “augmented reality” apps for the iPhone). Each book has its own macguffin driving the suspenseful plot (a search for the source of mysterious online footage or the unknown designer of a fashion line) but in many ways the action and the mysteries solved are not what’s important here. Gibson merely uses them as framing devices for an insightful meditation on technology, our increasingly global civilization, marketing, brands, fashion, trends and business. You’ll never look at London hotels, storage containers, penguins, and certain brands (“There must be some Tommy Hilfiger event horizon, beyond which it is impossible to be more derivative, more removed from the source, more devoid of soul.”) the same way again. Beyond the astute analysis, Gibson’s latest works are a joy to read. The precision of his language, the way he puts a sentence together, show him to be a master at the peak of his craft. One other quick book note from the year — I spent a certain amount of the summer re-reading George R.R. Martin’s pulp Wild Cards series. I had purchased the first volume in 1987, and dug it, along with the twenty-odd other books in the series, out of a box in my attic. This raises the question: if I buy a book today in any of the main e-book formats, will it be this easy (and free) to re-read that same book in 24 years?

Rick Anderson: I just finished reading “Townie” by Andre Dubus III. I’m not normally drawn to memoirs, but after reading a couple of glowing reviews of this one (and seeing that the author was from a hardscrabble mill town in eastern Massachusetts, not far from where I grew up), I checked it out and was immediately captivated. “Townie” is nominally a coming-of-age story, but in reality it’s a coming-to-terms story, or rather two: first, Dubus struggles his whole life to come to terms with his hugely gifted and startlingly irresponsible father (also a celebrated author, who left his wife and children for a series of other women and children); he eventually bridges the gap, with gently but deeply touching results. Second, he struggles to master and move beyond the violence that he had assiduously cultivated during his youth and young adulthood. As he gradually discovers himself as a writer he finds that the self-delusion that made it possible for him to justify constantly seeking out violent confrontation is stopping him from writing honestly and cleanly. This realization, too, eventually leads to a moving denouement. Dubus is a talented writer, and a wonderfully transparent one. He is also a careful thinker, one who holds himself accountable without the breast-beating and narcissism that mar so many memoirs.

David Wojick – “Social Networks and Health: Models, Methods and Applications” by Thomas Valente. Take a social network and call me in the morning? Actually this book is in part about the use of social network research in what are called public health interventions. Social interventions are a big deal in medical practice, ranging from trying to get people in rural developing countries to use medicine, to trying to get Americans to eat less. Interventions are a form of scientific communication, in their way. A lot of the progress in social network theory has been made in the context of these communication efforts, exploring how best to get groups to do what the doctors want them to. My interest however, and perhaps the interest of other Kitchen readers, is in understanding the social system we call science. I helped organize a research effort that used network analysis to study the emergence of new ideas in science, so I figured I should learn a little about network theory. This book is a good introduction, especially because of the real world health stuff. More than half of the book is really a textbook on network theory and applications. It does a good job with the basic concepts and quantitative measures, such as centrality, groups, positions, and diffusion of innovations, there being a chapter for each of these, and many more. Readers might also be interested in the results of my research group. They seem to have found a measurable transition in network structure that signals when a scientific community accepts a new basic idea, or paradigm. Previously scattered groups are seen to transition into an integrated network, self organizing as it were. See “The dynamics of scientific discovery: the spread of ideas and structural transitions in collaboration networks ” and “General Critical Properties of the Dynamics of Scientific Discovery”. This research builds on our earlier efforts to use the methods of disease epidemic modeling to study the rise of new ideas. See “Report for the Office of Scientific and Technical Information: Population Modeling of the Emergence and Development of Scientific Fields” and “Population modeling of the emergence and development of scientific fields,” Scientometrics, 2008. This all goes to show that social health research and the science of science have methods in common. This commonality is a good example of a general point I tried to make earlier this year here in the Kitchen, which is that methods cut across the sciences and have a life of their own. This work has implications for scientific communication and publishing. After all, trying to get new ideas out into the system is an intervention. Understanding how networks work can be a useful approach. Valente’s book is a good place to start.

David Smith: “We are today as far into the electric age as the Elizabethans had advanced into the typographical and mechanical age. And we are experiencing the same confusions and indecisions which they had felt when living simultaneously in two contrasted forms of society and experience.” – Marshall McLuhan, 1962

“The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood,” by James Gleick is my book of the year. This grand voyage takes you through the history of information, the history of humanity, from the invention of writing to the works of Babbage, Lovelace, Maxwell, Godel, Turing, and Shannon. In world of books with catchy titles and magazine length arguments fluffed out to 200+ pages, here stands a towering work of intellectual magnificence. A densely written, challenging read with moments of brilliance and insight that will have you thinking long into the night. You’ll need your wits about you, but this isn’t some dry tome that’s hard to digest. Gleick is the Aaron Sorkin of non-fiction, able to put phrase, paragraph, and page together in a manner that can be breathtaking at times. There is an argument put forward that the new lords of the information; Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon and Microsoft can’t do what we in publishing do, because they lack the skills, no, the mind-set, to do so. If you think that, then this book will surely make you think again. It will give you an important perspective about what it is that we actually do when we talk about publishing. Concepts like the identifier problem, the network effect, the difficulty of understanding the implications of a new technology, all are covered here in a manner refreshingly free of ideology. But then there are the bigger issues — what does a world of information look like when “insight” and “understanding” can suddenly appear, emergent from the billions of exchanges of humans in an always connected state, throwing out bits of profound significance and utter banality in parallel? The industrial revolution gave us the citizen as a unit of work. The Information revolution gives us the citizen as a unit of data. This book gives a grounding in just how we got to be where we are today, and sets up some of the questions that will be answered as we move further into the information.

Tim Vines — My favorite book of the year was “Surface Detail,” by Iain M. Banks. It’s his masterpiece of the Culture series, in that it tackles a neglected part of his universe (death) and builds a brilliant and sometimes horrific story around it. Bank’s science fiction books can struggle to balance the human stories with the hugeness of space and impossibility of the AIs, but “Surface Detail” lets the small and irrational choices of organic life drive events across a huge scale. His vision of a civilisation that has effectively made its own omniscient and omnipotent gods and have them co-exist in relative peace is compelling, but it’s the little details that you come away with. For example, what does an AI that thinks in picoseconds do to entertain itself while it’s waiting for humans to finish their sentences?

Discussion

7 Thoughts on "Chefs' Selections: The Best Books Read During 2011"

Regarding “The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood,” by James Gleick. Rather than saying “The industrial revolution gave us the citizen as a unit of work. The Information revolution gives us the citizen as a unit of data,” I would prefer to say the citizen is now a unit of thought. We have invented the cognitive production system. Data sounds like measurement, and while there is a lot of that too, most people in developed countries now think for a living, producing no tangible physical product at the end of the day.

To the Chefs: Thank you for these reviews! A welcome gift.

To Joe: After reading Ahab’s Wife (which I loved; read it if you haven’t) I went back to Moby Dick, but just couldn’t stay the course. I love the subject matter and have read a lot about whaling in New England, but I just couldn’t engage. It did feel like assigned reading.

To Rick: Can’t wait to read Townies. Thanks for the tip.

Of interest and relevance to TSK are two books on copyright I read and reviewed this past year for the Journal of Scholarly Publishing: William Patry, Moral Panics and the Copyright Wars (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), and Patricia Aufderheide and Peter Jaszi, Fair Use Reclaimed: How to Put Balance Back in Copyright (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011). Though both reflect a copyleft point of view, Patry’s is a very one-sided diatribe that contributes little positively to the debate whereas Aufderheide and Jaszi’s is far more balanced, even criticizing some copyleft positions along the way, and makes a solid contribution by showing the advantages of developing “best practices” of fair use by disciplinary area. I concluded my review of their book thus: “Overall, the authors’ strongly voiced support for understanding fair use as ‘transformative use’ should make their book welcome in scholarly publishing circles, one that those of us in this business could recommend to students and faculty as providing a generally sound and sane appreciation for what fair use can contribute toward the more balanced interpretation of copyright that it is their aim to promote.”