Last month, the editor and the editorial Board of the Journal of Library Administration (JLA) resigned en masse over the copyright policies of JLA’s publisher Taylor & Francis. The editors claimed that the T&F author agreement is “too restrictive and out of step with the expectations of authors.” Not surprisingly, T&F disputes the characterization of their copyright transfer policies. There has been a fair bit written about the editors’ and Board members’ reactions. Realistically, will the actions of this Board affect change either for JLA, Taylor & Francis, or, more broadly, the field of library and information studies scholarship?

This is not the first time that an editorial group has quit in protest over a publisher’s policies. Over the past 15 years or so, there was something of a movement by editors to quit old established journals in protest and form new journals in the hope that they could transform scholarly communications by supporting new business models or approaches — while simultaneously damaging the brand of titles that were viewed as unfavorable to library or scholarly interests. As movements go, it was modest in size. Peter Suber maintained a list of 14 different instances when journal editors or editorial boards resigned, 12 of whom left to start up new titles. (Fourteen titles are listed, but one did not launch a new title, while another was never launched by the original commercial press.)

Suber’s list only covers activity between 1989 and 2004. It appears most of the information was moved to a more up-to-date list of Journal Declarations of Independence that is hosted by Simmons College as part of the Open Access Directory (OAD) wiki.

The OAD list includes 22 titles, including the recent announcement of the JLA board. As movements go, the “independence” movement of journal editors is very modest in size; considering the number of academic journals is more than 25,000 according to the International Association of Scientific, Technical and Medical Publishers (STM), it represents only 0.088% of all scholarly journals. To be fair, many more editors, authors, and activists have simply moved quietly to publishing new OA titles and stopped publishing in traditional journals without “declaring their independence.”

An important question is whether these declarations have had an impact on the individual title that was being boycotted. Did the decision by the editors have any impact that transformed scholarly communications as they usually claimed they desired or envisioned? One cannot deny the successes of the OA movement over the years, but what impact is this related movement having on the traditional publishing environment?

The results of the “independence movement” appear mixed.

Of the 22 titles that experienced an editorial revolt, almost all continue to be published today by their original publisher. In most cases, the boycotted title has continued to thrive. It is difficult to know exactly the impact on the state of the journal after a boycott, since the key metrics of a journal’s success — such as its circulation, its finances, its download figures, and its submission and rejection rates — are usually closely held. One of the more public assessment criteria is a journal’s impact factor. With the kind assistance of Marie McVeigh, Director, JCR and Bibliographic Policy at Thomson Reuters, we’ve compiled impact factors of the titles that were noted on Suber’s list and their associated new journals.

Of the 12 titles on Suber’s list that left to start up new titles, 10 have comparable impact factors between the old journal and the new journal. Of those where no comparison is possible, one of the new titles is not ranked by Thomson Reuters and, for the second, neither the original nor subsequent journal was ranked in the impact factor. I’ve compared these available data in Table 1, below.

Of the other 10 comparable titles, six have an impact factor greater than that of the title from which the editors split at the time of the split. Four of the new titles have impact factors that are less than the boycotted title’s IF at the time of the split. Compared to the current IFs of boycotted titles, the IFs look a bit better for the new journals; seven of the new titles were better rated than the title that was subject of the revolt. The average impact factor of the new title is more than 50% greater than the boycotted title, with one outlier that is more than five times better off than the boycotted title.

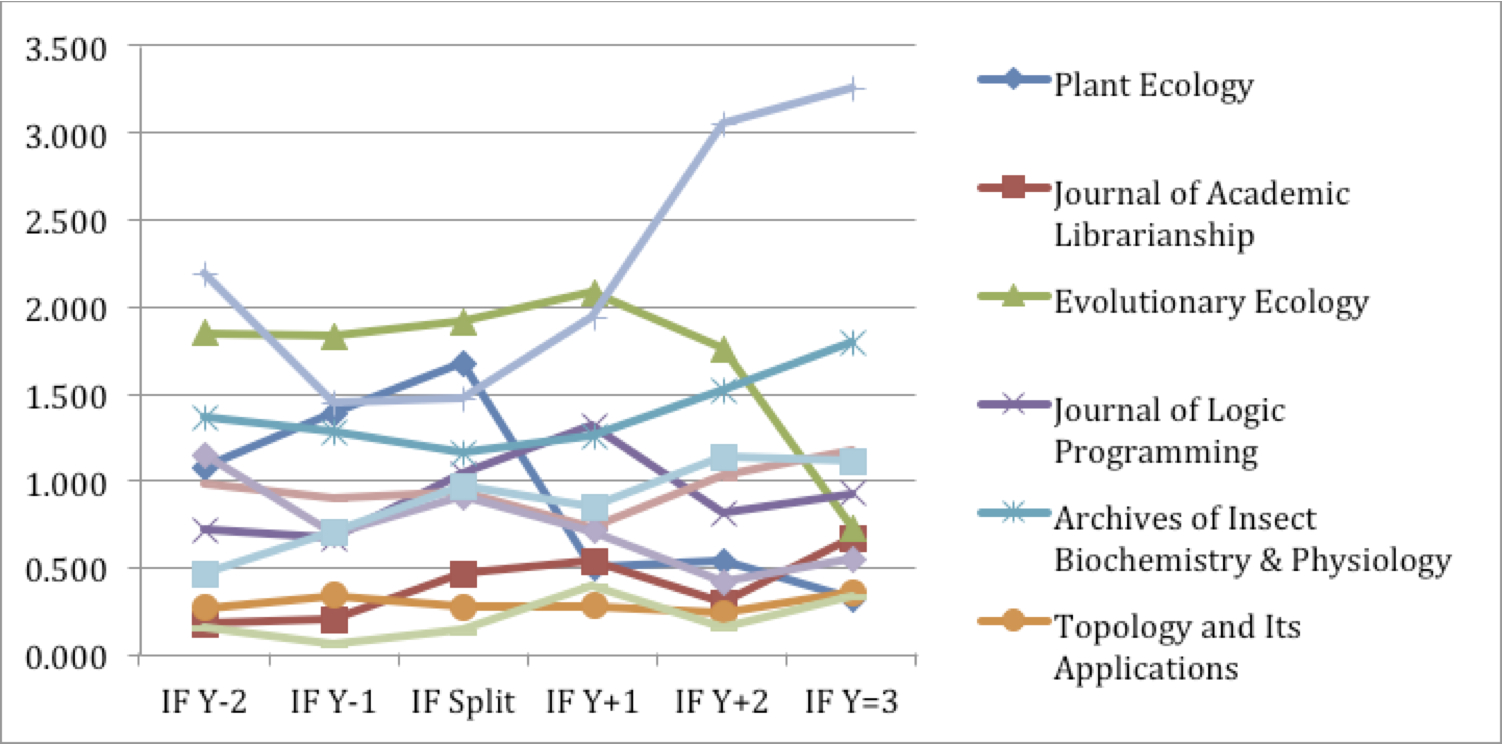

The boycotts seem not to have caused long-term damage on those titles, however. Of the 11 titles ranked, nine of the titles have higher impact factors than at the time of the split. Those titles that improved increased their IFs by an average of 33% from the time of the split. The two that experienced a drop today from their pre-split highs — Journal of Logic and Algebraic Programming and Journal of Algorithms — were titles where there was organizational sponsorship was withdrawn and given to a new title. These two have seen the greatest decline of IF today from their IF rankings at the time of their split; however, they both actually saw an increase in the IF rankings from the time of the split to three-years post split (see Figure 1, below). Perhaps this was due to the paper flow of manuscripts that were already accepted by the publication and remained in the pipeline after the split. The ties of these two publications to organizational supporters is probably the strongest predictor of the success of the subsequent title. One caveat to this theory is that neither of the newly-created corresponding titles have reached the IF of the boycotted journal at the time of the split.

Table 1: Impact factor (IF) comparison between title experiencing editorial revolt and newly formed competitive journal

|

Old title |

Year of Split

|

IF old title at time of split (a) |

IF old title today (b) |

IF as % of old IF (b/a) |

New Title |

Current IF new title (c) |

New title IF as % of old title (c/b) |

| Plant Ecology |

1989 |

1.676 |

1.829 |

109% |

Journal of Vegetation Science |

2.77 |

165.3% |

| Molecules (Springer) * |

1996 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Molecules (MDPI) |

2.386 |

N/A |

| Journal of Academic Librarianship |

1998 |

0.462 |

0.586 |

127% |

portal: Libraries and the Academy |

0.75 |

162.3% |

| Evolutionary Ecology |

1998 |

1.916 |

2.453 |

128% |

Evolutionary Ecology Research |

1.029 |

53.7% |

| Journal of Logic and Algebraic Programming |

1999 |

1.042 |

0.506 |

49% |

Theory and Practice of Logic Programming |

0.667 |

64.0% |

| Archives of Insect Biochemistry & Physiology |

2000 |

1.159 |

1.361 |

117% |

Journal of Insect Science |

0.947 |

81.7% |

| Topology and Its Applications |

2001 |

0.280 |

0.445 |

159% |

Algebraic and Geometric Topology |

0.558 |

199.3% |

| Machine Learning |

2001 |

1.476 |

1.587 |

108% |

Journal of Machine Learning Research |

2.682 |

181.7% |

| European Economic Review |

2001 |

0.926 |

1.527 |

165% |

Journal of the European Economic Association |

1.357 |

146.5% |

| Labor History |

2003 |

0.138 |

0.24 |

174% |

Labor: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas |

N/R |

N/A |

| Medical Informatics & and Internet in Medicine |

2003 |

0.915 |

1.04 |

114% |

Journal of Medical Internet Research |

4.663 (2010) |

509.6% |

| Journal of Algorithms |

2003 |

0.974 |

.50 |

51% |

Transactions on Algorithms |

0.932 |

95.7% |

| Notes:* Molecules was never actually published by Springer, it was moved to its current publisher prior to the first issue. | |||||||

All of the standard caveats about impact factors apply here. Most journal impact factors fluctuate from year to year, so some variation is to be expected. This is especially true of titles with impact factors as low as many of the titles included in this analysis. How much fluctuation is attributable to the editorial board’s departure is an open question. Table 2 lists the boycotted titles’ IFs for three years following the split and Figure 1 compares the changes.

Table 2: Impact Factor Trends 2 Years Prior to and for 3 Years After the Editorial Revolt

| Old title |

Year of Split |

IF Y-2 |

IF Y-1 |

IF Split |

IF Y+1 |

IF Y+2 |

IF Y+3 |

| Plant Ecology |

1989 |

1.083 |

1.384 |

1.676 |

0.507 |

0.536 |

0.326 |

| Molecules (Springer) |

1996 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

0.248 |

| Journal of Academic Librarianship |

1998 |

0.179 |

0.208 |

0.462 |

0.542 |

0.296 |

0.671 |

| Evolutionary Ecology |

1998 |

1.850 |

1.830 |

1.916 |

2.087 |

1.762 |

0.733 |

| Journal of Logic and Algebraic Programming ** |

1999 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

0.733 |

| Journal of Logic Programming ** |

1999 |

0.721 |

0.675 |

1.042 |

1.319 |

0.819 |

0.929 |

| Archives of Insect Biochemistry & Physiology |

2000 |

1.364 |

1.280 |

1.159 |

1.260 |

1.525 |

1.800 |

| Topology and Its Applications |

2001 |

0.270 |

0.346 |

0.280 |

0.285 |

0.238 |

0.364 |

| Machine Learning |

2001 |

2.190 |

1.447 |

1.476 |

1.944 |

3.050 |

3.258 |

| European Economic Review |

2001 |

0.980 |

0.893 |

0.926 |

0.726 |

1.021 |

1.169 |

| Labor History |

2003 |

0.152 |

0.056 |

0.138 |

0.395 |

0.159 |

0.333 |

| Medical Informatics & and Internet in Medicine |

2003 |

1.155 |

0.698 |

0.915 |

0.717 |

0.419 |

0.551 |

| Journal of Algorithms |

2003 |

0.468 |

0.704 |

0.974 |

0.849 |

1.138 |

1.119 |

| Notes:* Molecules was never actually published by Springer, it was moved to its current publisher prior to the first issue.** Journal of Logic Programming changed its title to the Journal of Logic an Algebraic Programming in 2002. The IF of JLP in 2002 (IF Y+3) is a combination of the two titles’ IFs for that year. | |||||||

In the short term, the boycotts did appear to have some impact. Five of the 11 titles showed some significant drop in IFs in the three years following the editorial split. In some cases, such as Evolutionary Ecology and Plant Ecology, the precipitous drop in IF three years after the split is most likely due in part to the editorial board’s departure. However, both of those titles have regained, even improved on, their IF at the time of the split.

What is particularly interesting about Evolutionary Ecology is that while the IF dropped significantly, the newly launched title Evolutionary Ecology Research never reached the stature of Evolutionary Ecology and has a current IF that is roughly half of the boycotted title’s IF factor in 1998, the year of the split (see Table 1). Meanwhile, Evolutionary Ecology’s IF is up 28% from its IF at the time of the split.

Figure 1: Impact Factor Trends 2 Years Prior To and 3 Years Post Editorial Revolt

Source Data: Thomson Reuters Journal Citation Reports. Many thanks are due to Marie McVeigh and Thomson Reuters Scientific for supplying these data.

I have a particular interest in this topic since I was involved, in a small way, with one of these new “independence journals.” Back in the late 1990s, the entire editorial board of the Journal of Academic Librarianship resigned after Elsevier acquired the journal as part of its purchase of JAI Press. Several of the editors who resigned approached the Johns Hopkins University Press (where I was Journals Marketing Manager) and launched a new journal, portal: Libraries and the Academy. One of the new editors, Gloriana St. Clair, penned an editorial comment in the inaugural issue on the need for a new journal. I will let you all decide if the goals outlined in that editorial have been fully realized. However, portal has proved itself a significant new journal in the community, with an impact factor that is 162% of the IF of the Journal of Academic Librarianship at the time of the split and a higher IF than JAL’s today. Much like most of the journals analyzed, JAL is doing fine, with its own IF increasing 28% since the departure of the editorial board. There was a brief dip in the IF of JAL two years after the departure of the board, but it quickly rebounded. In fact, it quickly surpassed its pre-split IF.

The data appear to show that while the place or ranking of the original title generally remains about the same, the new journal tends to thrive. From the perspective of a librarian who needs to hold a comprehensive collection, both titles are likely acquired, if budgets permit. The proliferation of titles in this manner, though, certainly makes the selection process more challenging for acquisitions librarians.

Probably since the original title remains available via some form of “Big Deal” journal package, it’s unlikely that the circulation of the original title dropped much. The new title may benefit from the press about the editors and their enthusiasm or promotion among its proponents in the community. In all likelihood, there was a nascent need for a new title, simply because the amount of published literature in the field is growing over time — another reason for the success of both titles. This growth is likely providing an opportunity for less senior researchers, because the more established writers, who are less bound by the need for a brand-name title to be attached to their CV’s can move to the newer title without risking their careers by publishing in less-established titles. The younger researchers can more easily get their content published in a “reputable” top-tier journal because more established authors are no longer crowding them out. This also explains why the newer title often has a higher impact factor because more senior authors are contributing their content there rather than the boycotted title. By creating a market for publication venues, there might be a greater ability of authors to pick and choose the issues or publisher policies that are important to them. Eventually, the newer title may become the more prestigious, but that takes time, and the boycotted title will be likely retain its laurels for some considerable term. It seems that comparing the IFs of the new titles to the established ones, the new titles are more likely to take a higher-ranking position in the quality race, though this isn’t the case for every publication.

The rising tide of publication seems to be raising all the journal “boats” in the sea, rather than the new title cannibalizing the old in a simple zero-sum publications ecosystem.

Sweeping proclamations about some movements can get a lot of attention for the participants. But this is often the flash of light, not the shock wave of the explosion — bright but not anywhere near as impactful. The bigger trend is usually the one happening below the radar — where long-term change will take place. This certainly seems true of OA. Despite the coverage these “declarations of independence” garner, their impact on the scholarly communications ecosystem seems quite muted. If the goals were to open new quality channels under new terms, than the mutineers may be said to have had success. But for the larger goal of affecting change on the old guard titles, the mutinies in general can’t be said to have had the same success beyond the media flash of editors’ jumping ship.

Discussion

4 Thoughts on "Splitting the Difference — Does an Editorial Mutiny at a Journal Do Much Long-term Damage?"

Todd, a really excellent post to a topic that hasn’t received much rigorous analysis. Thank you for this original contribution. The resignation of a board is strategic: A group of academics is unlikely to jump ship unless there is another boat waiting to take them aboard. This means that this kind of behavior is only likely to take place in healthy seas with an abundance of fish (research authors). In other words, both ships are not competing for a limited number of manuscripts–there are enough for both boats to catch–and one would imagine that both ships could continue to fish (and thrive) in the same waters.

Obviously, there is still plenty of room for new journals …

Probably this room for new journals, mainly open access journals in the past ten years, is benefiting not only the open access movement, but it is also providing the younger, less-established researchers to get their articles published in traditionally “high-impact” journals. Less-established authors would have found it more difficult to get their articles published if they were being crowded out of traditional titles because the acceptance rate was so low. This is the reverse of the strategy that Nature has been employing for more than a decade now–create a new title when you have enough “second-tier” content (BTW – not disparaging any Nature titles).