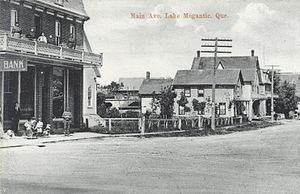

The tragedy of the train wreck and oil fire in Lac-Mégantic, Québec is, first and foremost, a human one, with close to 50 people killed and the homes and businesses of many survivors destroyed. But a smaller tragedy has also come to light, one that should give pause to libraries and the institutions (academic and political) that sponsor them.

A recent article in Library Journal reports that one casualty of the explosion and fire in Lac-Mégantic was the village’s library and its collection, “which included more than 60,000 books, CDs, and DVDs, and a local history archive.”

The loss of the commercially-published books and recordings held in the library’s general collection is truly unfortunate—but the loss of the archive is tragic. As the article points out,

The library started gathering historical documents and personal effects from residents in 1996, and the collection had since grown to include everything from local social club records to the earliest known photos of the town to information about Donald Morrison, a Lac-Mégantic resident and notorious 19th century outlaw.

Québec Public Library Association Executive Director Eve Lagacé added: “The library had only recently received many historical and personal archives; not everything had been cataloged.”

Over the past two decades, as the shift from a print-based information environment to a digital and networked one has gradually become a foregone conclusion, there have been voices of resistance—some of them loud and prominent—warning us that digital formats are fragile if not evanescent, that digital standards inevitably obsolesce, that cloud-based service providers are unreliable, and that not everyone has access to a networked computer. These things are all true.

But Lac-Mégantic points up something else that is also true: if a document is unique, it’s uniquely at risk. Truly effective archiving has to mean more than simply putting unique documents in a safe physical location—because ultimately, there’s no such thing. Every year we hear stories of libraries and archives being flooded, burned, burgled, or shaken to pieces, their collections (including unique, irreplaceable documents) destroyed in ways both unimaginable and all too predictable.

The explosion in Lac-Mégantic destroyed the unique photos and documents of the library’s archive, but it need not have made the content of those documents forever inaccessible to the town’s residents and interested parties around the world. If they had been digitized, uploaded to robust and secure networked servers, and mirrored in multiple locations, we would all still have access to them—not to the documents themselves, unfortunately, but at least to their images and intellectual content. None of those online copies would be perfectly safe either, of course—but the existence of digital copies in many locations would make it far less likely that their content would ever be lost for good.

Every library needs to pay attention to this lesson. Unless we are digitizing our unique materials and placing copies in robust digital repositories, we are playing with fire. This doesn’t mean that we should stop doing our best to safeguard the physical documents themselves, of course—it means only that if we believe such measures are sufficient to safeguard their content, it’s time to stop kidding ourselves.

(For a more developed argument along these lines, see my recently-published white paper Can’t Buy Us Love: The Declining Importance of Library Books and the Increasing Importance of Special Collections.)

Discussion

19 Thoughts on "Lac-Mégantic and the Importance of Digital Archiving"

I could’t agree more. One vision I’ve had for the DPLA (and similar efforts in other countries) is for a cooperative network that begins at the local level with special collections such as this library had been building, working with the town’s citizens and local historical societies to assess the value of and then digitize important documents like diaries, business records, correspondence, photos, etc., so as to allow these to be accessed by everyone, but particularly scholars who would use them as archival sources to construct their narratives and analyses, which in turn would then feed into the writing of textbooks and popular books for the general public, all coordinated through the top-level network of a DPLA. The permanent loss of this kind of local collection renders such a project incomplete. Every effort should be made to use the digital technology we have at our disposal to safeguard such unique records for posterity.

Your white paper is very interesting. You argue that libraries should make a major shift away from buying commodity (that is, recently published) documents, especially books, and invest much more of their budgets in the digital curation of unique historical documents. There are some assumptions that need to be questioned, such as whether these old documents are as valuable as library services used to be (but apparently no longer are)? Whether the emerging ultra-cheap used book market can replace library services, as you suggest, and so on? But it is a bold proposal.

On the historical document side I recommend a focus on the history of technology, which I used to teach. Little has been written on it and it is very hard to track, so it is poorly understood. You are however competing with historical societies and museums.

There are some assumptions that need to be questioned, such as whether these old documents are as valuable as library services used to be (but apparently no longer are)?

One important clarification: my argument is not that “library services” are less valuable than they once were, but that the very specific library service of collecting, organizing, and caring for commodity books is less valuable than it once was. “Library services” covers a much, much broader array of activities, most of which are outside the scope of my paper (and many of which I believe to be of enduring and, in some cases, increasing value).

Sorry, but one more clarification: my paper does not equate “commodity documents” with “recently-published” documents. It characterizes as “commodity documents” those that are easily found, bought, and sold in the conventional marketplace. Dickens’ Great Expectations was not recently published, but most copies and editions of that book would count as “commodity documents” in my formulation, whereas the manuscript version, or a handwritten letter by Dickens, would not.

I’m sorry, but you’re going in the wrong direction.

First of all, for a small town such as Lac-Mégantic to undertake the work necessary to digitize their archival holdings would require funding that is probably simply not available to them. To advocate for such a thing is fine, but it takes money and expertise to make it happen and even more to maintain the digital collections going forward. And in case you hadn’t noticed, the the governments of both Canada and the United States have been reducing support for these efforts. The current budget proposal for the NEH (one of the prime funders in this area in the US) is a reduction of around 45% for the next period. That bodes ill for future projects …

Secondly, “Truly effective archiving has to mean more than simply putting unique documents in a safe physical location—because ultimately, there’s no such thing…” reflects an imperfect understanding of just what archivists really do (oh, and they don’t really like that word “archiving” except when talking amongst themselves). It isn’t an issue of being “truly effective.” And your suggestion that there are no safe physical locations apply just as strongly to the digital domain as it does to the physical one. One of the most difficult concepts for people both inside and outside the profession to come to grips with is the essential impermanence of EVERYTHING. Among other duties, the job of the archivist is to arrange for the long-term preservation of the materials in their care. Not permanent, but “long-term.” You can thank the media and the hysterical for leading us to believe in permanence.

Third, I don’t know your experience with local historical society collections, but they are often more than simply documents and photographs. Digitizing three dimension objects is often beyond these institutions, yet they represent another dimension of the material culture and history of a place and people.

Make no mistake: Lac-Mégantic was a tragedy. Could there have been things done to reduce the impact on the collections? Probably. But given the constraints of time needed and monies required to have digitized their collections, your suggestions smack of being a Monday morning quarterback.

You and I agree completely on a number of points. First, my comments amount to Monday-morning quarterbacking (unfortunately, on Monday morning that’s the only kind of quartebacking possible). Second, without money you can’t do much in the way of truly robust and thorough digital archiving (however, basic digitization, such as quick scanning, can be done for most documentary materials at minimal cost; libraries should consider whether they need to redirect staff time from less-important tasks to at least this basic level of digitization). Third, my use of the term “archiving” in this piece is colloquial, not rigorous. Fourth, three-dimensional realia do indeed pose digitization challenges that two-dimensional documents do not (but that’s no excuse for failing to digitize the things we can). And fifth, everything is indeed impermanent; there is no perfect archival solution. Nor were my comments really intended as a criticism of the managers at the Lac-Mégantic library—they were intended as a heads-up to the rest of us, pointing out the illusory nature of the “permanence” of physical formats and the importance of doing what we can to create images of unique materials and putting those images somewhere relatively (though not perfectly) safe.

Note that Rick is advocating diverting a lot of the present book budget to historical curation. Even in a smallish town this is a substantial new amount for historical use, but one that already exists. He is not calling for a budget increase. The question is whether this shift is a good idea or not? It is not a question of new funding.

Sorry to keep jumping in with corrections and clarifications here, David, but I need to point out that the more aggressive recommendations in my white paper are aimed at academic and research libraries, where usage of what I’m calling “commodity books” is dwindling and where Special Collections holdings tend to be more extensive. In small public libraries such as the one at Lac-Mégantic, where usage of commodity books tends to be much steadier and stronger and unprocessed Special Collections holdings smaller, I would generally advise a more conservative approach to redirecting resources. Obviously, every library’s decision-making has to be guided by institutional mission and priorities.

There is no such thing as “basic” digitization: you’re in for the whole thing or you’re not in at all. Much damage has been done by the “casual” digitization; this is completely analogous to the wild and crazy days of microfilming everything because it was seen as the salvation solution. A quick bad scan is nearly as bad as no scan at all … and when you’re budget is as limited as many of these local history collections’ are, there is no “minimal cost” — they’re understaffed and under-funded.

If anything, this should be a heads-up directed to the ALA, ACRL, RBMS, and SAA for collective action against the politicians, from local to national, who are continually hamstringing our efforts.

There is no such thing as “basic” digitization: you’re in for the whole thing or you’re not in at all.

Baloney. Even low-res .pdfs produced quickly by student employees working at minimum wage on a $50 flatbed scanner from WalMart would be far better than what we now have of the unique documents formerly housed in the Lac-Mégantic archive – which is to say, nothing. In libraries we tend not only to make the perfect the enemy of the good, but also to take foolish pride in that tendency – and that’s one reason for the tragic loss of unique content that happens every time a library is flooded, burned, etc.

If anything, this should be a heads-up directed to the ALA, ACRL, RBMS, and SAA for collective action against the politicians, from local to national, who are continually hamstringing our efforts.

That may be true. But the lack of political support is no excuse for libraries to fail to reexamine the current allocation of their resources in light of the lessons offered by Lac-Mégantic. The question we should all be asking ourselves is: are we devoting our limited resources to tasks that are less important and less urgent than digitization? If not, then great. If so, then it’s time to consider redirecting those resources. By all means, let’s work for political change. But in the meantime, let’s get to work. Waiting around for politicians to share our priorities is not going to get us anywhere.

I strongly disagree with your assertion that “a quick bad scan is nearly as bad as no scan at all” – compared with 100% loss, even a marginal scan of something irreplaceable is a big win. For a small institution, the hardest part is the logistics and that’s not an insurmountable barrier – if you have a process for storing scans and replacing them when time / budget become available, even finding students or engaging local volunteers (after all, in cases like this, many of the documents are personally relevant to many in the community) is better than doing nothing. A few hundred dollars worth of scanner / DSLR and a cloud backup account is a reasonable expense for your most unique holdings – and a great base to use when pitching prospective donors or funding agencies for help expanding the program.

One project I’d like to point out is the interesting Project Gado: http://projectgado.org/ This is a very similar situation: a small archive in Baltimore with a very limited budget, building a $500 scan robot. It’s not going to replace a high-end commercial system but if buying one is never going to be realistic, it’s a huge step up from doing nothing and hoping perfection will arrive before something is lost forever.

It’s your option to “strongly disagree” but you might want to re-read my statement. A marginal scan is NOT a “big” win … there are enough garbage scans out there that are of extremely limited use. It doesn’t take that much more time to do a good job that will not require re-scanning.

Several of you have made the situation of losing materials sound absolutely dire. If that’s how you feel then put your energies into doing a job that doesn’t require being done AGAIN because you may not have another chance to get it right. And I said “right” not “perfect.”

You don’t have the option of “… storing scans and replacing them when time / budget become available…” … do it once, do it right, and move on.

I don’t know what you pay your students, but the historical societies I know probably couldn’t afford them; the last three institutions I was at were not in much better shape when it came to being able to hire students for digitization work, much less the necessary metadata work to make the things useful.

I’m not saying anything about “perfect” digitization (please re-read my comments); I AM saying that it’s worth the time to do it right the first time because you likely won’t get another chance. And it doesn’t take that much time or effort to do it right. So what you’re advocating for is inappropriate (low-res pdfs, etc.,).

Nor did I say anything about “Waiting around for politicians to share our priorities” — indeed, I’m actually calling for radical action against any politician who does…if they’re elected, then vote them out, if appointed pressure the elected ones to get them out.

I suppose we should agree to disagree …

I’m not saying anything about “perfect” digitization (please re-read my comments)

All-or-nothing rhetoric like “you’re in for the whole thing or you’re not in it at all” is an example of letting the perfect be the enemy of the good.

Uhm, no — what I’m saying is that you either digitize or you don’t. Period. As for “perfection” you’re that one that raised that specter in your sixth paragraph … but I can see that we have less and less to agree upon, so I’m done with this.

Modern scanning equipment, in which I include digital cameras, can produce excellent results at minimal costs.

My wife’s family spent two years in France during the 1950’s, and my father-in-law created a wonderful photographic record, an irreplaceable family treasure. The photos sat for a half century in an album before we decided a backup was needed. Using a digital SLR with a good professional lens, I photographed each print along with each page (to capture the captions and context). It took only a day to record some 800 photos.

The treasured photos now reside safely on CDs distributed among the family. Quality? The surprise is, with the ability to enhance and enlarge the digital images on Photoshop, we are seeing details we did not notice before.

At a local high school, sophomores are required to do a community service project. If 20 students were to each digitize some books, an historical photo album or scrapbook, and work with an archivist to research and input the meta data and appropriately store the results, this could create a substantial historical resource. For local history like the Lac-Mégantic material, this could be an ideal solution.

This is a great idea, and certainly feasible. As my experience with a family album demonstrates, even modest skill level can capture 80-90% of the signal in the source materials. That’s a lot better than nothing.