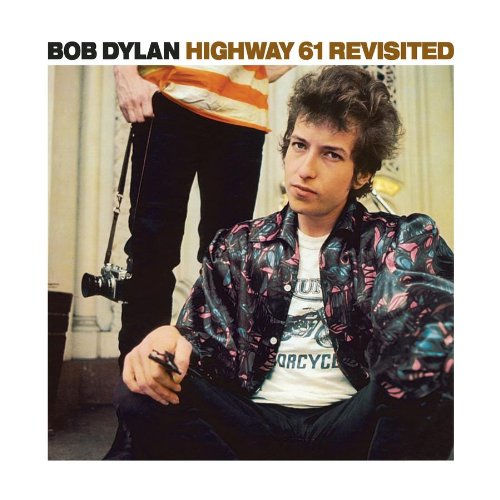

Yes, the title of this post is a cheat. About thirty years ago Mark McCormack wrote What They Don’t Teach You at Harvard Business School, which became a huge bestseller. The pose of the book is that the academy, even a business school, is sorely deficient in the ways of the world (the subtitle is Notes from a Street-smart Executive). I have never been persuaded by this line of thinking, as it has always seemed to me that our society is separated into different spheres, each of which operates with its own internal physics. Being street-smart helps when you are on the street, but may be unhelpful in crafting far-reaching social policy; developing an elaborate model that spans industries and even generations may be a superfluity when you are stopped by someone waving cash and insisting that here is a deal for you. Please forgive me this indulgence, but I am writing this while on vacation and no one said this better than Bob Dylan:

You said you’d never compromise

With the mystery tramp, but now you realize

He’s not selling any alibis

As you stare into the vacuum of his eyes

And say do you want to make a deal?

Still and all, every once in a while McCormack seems to have it just right. This is how I felt when I stumbled on a blog post at the site of the Harvard Business Review that is making its way across social media conversations about publishing. The author is Dorie Clark, who teaches at Duke’s Fuqua School of Business. The title of the piece is “Harper Lee and Dr. Seuss Won’t Save Publishing.” I know we can’t blame Clark for the title; there is an editor who will have to answer for this in the hereafter. But the argument of the piece is high-level and general; its nostrums are unconnected to the very industry it purports to cover. When we send out the RFP to work on this project, won’t we be better off giving the contract to the mystery tramp?

Where to begin? The notion that publishing must be “saved” implies that it is damned, but the facts don’t support this. Publishing is a mature, global industry whose growth is largely connected to macroeconomic issues: the rise of a literate middle class, the needs of professional disciplines. It would be nice if there were organic growth in the First World: more people reading more books, a worldwide commitment to higher standards of education, a large increase in outlays for research (I personally belong to the More Money for Research party), but I don’t see it happening. In any event, the difference between being mature and dead is very great–just ask anybody over 50. The publishing business is anything but dead; it is alive and complaining, as it has been for centuries. Don’t turn out the lights until the whining stops.

Clark’s argument is that publishing is relying on the unexpected appearance and success of two books that hearken to another age: Harper Lee’s Go Set A Watchman and What Pet Should I Get? by Dr. Seuss. Both books were written years ago (Watchman is the unsuccessful first draft of To Kill a Mockingbird) and now have surfaced at a time when their authors are beyond critical scrutiny. They will sell millions of copies. (One can only wonder what will happen if the rumor is true that J.D. Salinger left several completed manuscripts behind, which are to make their way to the marketplace in the coming years.) Publishers have to think beyond finding valuables in the attic, Clark says, and she proceeds to roll out a list of prescriptions (more on these in a moment). “The ‘forgotten treasure’ boom can’t last forever; there are only so many relics you can pull out of the archives.”

Readers of the Scholarly Kitchen by this point will note that Clark is committing the common error of confusing trade publishing with the entirety of publishing. So one would think that all that is necessary is to insert the word “trade” before every appearance of “publishing” and we are back on track. Alas, it is not to be: Clark cites statistics that books and journals comprise a $28 billion industry in the U.S. When you follow the link to her source, you come to a useful if misleading page from the AAP. It turns out that the reference to journals is simply a mistake (that is, Clark picked up the error from the AAP), as the itemization for the statistics refers only to books. But not just trade books but college, K-12, and professional books as well. It is difficult to imagine anyone in, say, medical publishing looking to save the business by rummaging through the attic. Or is Clark expecting a classic work on phlebotomy or the four humors to climb to the top of the bestseller list? The unfortunate fact is that when Clark references “publishing,” she really doesn’t know what she is talking about.

Having failed to properly identify her subject, Clark offers this bit of advice:

Let’s face it: most publishers have very little to offer authors when it comes to direct marketing, because (unlike Amazon) they generally don’t have buyer data or their own lists. . . . Instead, most publishers rely on the author to move copies by selling to his corporate clients, or her personal email list, leaving authors to wonder what, if anything, they’re adding to the marketing mix.

This paragraph (aside from overlooking the fact that virtually every book publisher nowadays sells books directly from their Web sites) makes one wonder why the AAP statistics are the ones to use at all. The AAP tracks publishers’ receipts, but if you are thinking about direct marketing, surely the figures to use to size the industry would be sales at retail. That would take that $28 billion figure (for all books, not just trade) up quite a bit. I have seen estimates that put the U.S. book business at $35-$40 billion at retail, but I don’t know how these numbers were put together. Figures for the global book industry are sometimes estimated as three times that amount, but, once again, I don’t know how those figures were derived. Even so, the business and its inherent opportunity is much bigger than Clark imagines. As Adam Sandler says, not too shabby.

So the data in this piece is simply worthless, but are the analysis and prescriptions valuable nonetheless? I’m afraid not. Some of what Clark recommends (e.g., be more transparent with data) are already being implemented by the major houses and her general prescription to forge closer relationships with authors reveals a complete lack of awareness of what is driving the business today. She notes (correctly) that author advances are down, but attributes this to publishers’ weakening position. How’s that again? If Wal-Mart were able to pay its vendors less year by year, is that because Wal-Mart is failing or because Wal-Mart has more economic leverage and can drive down prices? Clark has the situation backwards.

What’s really going on in book publishing today is that publishers are consolidating their market positions through mergers and acquisitions. This is true in trade, higher education, and (no surprise here) STM, as the emergence of Springer Nature attests. Book publishers for the most part are faced with the dominant position of Amazon, which puts upstream pressure on its vendors. Publishers in turn consolidate both to fend off Amazon and to squeeze down the share that authors take. Indeed, from a margin point of view, all the benefits of the migration from print to digital books have accrued to publishers. Authors are worse off (except for the very biggest) because the publishers thus far have been able to get away with this.

It’s hard to escape the conclusion that Clark’s is the voice of the spurned author. Can’t pull down that big advance? Don’t have the necessary platform to make a book marketable on a large scale? Well, it’s the publishing business that is at fault; if only it would partner with me, all would be well. The way to get rich is to make me rich.

I don’t think so; these are just alibis. While it’s true that sometimes the interests of publishers and authors are perfectly aligned, and sometimes the interests of publishers and libraries are aligned, it’s also true all these entities always jostle one another for a preferred position in the marketplace. Thus if someone wants to provide guidance for publishers, it’s fundamental that the perspective should be that of a publisher. The game is not played at the high level of “the industry” or “the system” but on the ground, by experienced professionals. The key to crafting a successful strategy is domain knowledge, and it helps not to be overly influenced by what you read in the mainstream press, as it skews heavily toward recent developments in the trade sector. I think it’s about time to give the mystery tramp a call.

Discussion

4 Thoughts on "What They Still Don’t Teach You at Harvard Business School"

One might point out to Ms. Clark how difficult it has been to close down a university press. In the past fifty years there have been efforts to shut down a few small presses, like Arkansas. Most of these have failed in the face of stiff counter-pressure. Only a very few have actually closed–SMU, Rice (twice), and now possibly Akron (though the administration there claims that its functions are merely being transferred to the library). No larger press has even been in danger of closure. So, with respect to this segment, she is clearly entirely off base. There are no deaths in this sector going on, except perhaps at the very margins and with minimal effect. Indeed, on the contrary, many academic libraries have come to call themselves publishers, or have even given birth to university presses (as at Amherst).

Her article seems thoughtful enough, mostly about star writers and the threat of self publishing in popular books. She says this at the end: “Despite the dire news surrounding it, the U.S. book and journal publishing industry is still doing well, bringing in nearly $28 billion last year, a 4.6% uptick from the year prior.”

So what is not taught at the business school? Know whom you’re dealing with. Show that you know. Work toward the greater good of all concerned. Try this, globally, with authors, publishers, marketers, and–who knows–the reading public. Appeal to all constituencies and aim for success via the win-win.

Thanks for this piece. It’s terrific and timely.