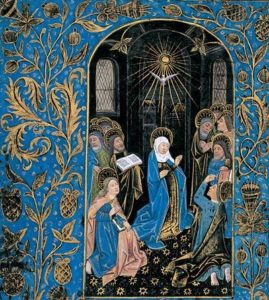

While I did not choose it as my 2015 Book of the Year (see Part I of the Chef selections here), I want to draw my colleagues’ attention to Eamon Duffy’s work, Marking The Hours: English People and Their Prayers 1240-1570 (Yale University Press, 2006). The Irish historian documented the emergence and historical development of the medieval Book of Hours which were, at one time, produced in greater volume than copies of the Bible itself. At the height of their commoditization, they were crudely printed volumes, but many museums and libraries value and preserve specific examples as rare works of art. Such volumes may have been produced with a certain intention as to use (that of devotional aid), but Duffy writes of the historical value of these artifacts in some other contexts — that of luxury good or status symbol, as a form of documentation indicating family position in relation to power, as a marker of an individual owner’s existence in a specific time and place.

While I did not choose it as my 2015 Book of the Year (see Part I of the Chef selections here), I want to draw my colleagues’ attention to Eamon Duffy’s work, Marking The Hours: English People and Their Prayers 1240-1570 (Yale University Press, 2006). The Irish historian documented the emergence and historical development of the medieval Book of Hours which were, at one time, produced in greater volume than copies of the Bible itself. At the height of their commoditization, they were crudely printed volumes, but many museums and libraries value and preserve specific examples as rare works of art. Such volumes may have been produced with a certain intention as to use (that of devotional aid), but Duffy writes of the historical value of these artifacts in some other contexts — that of luxury good or status symbol, as a form of documentation indicating family position in relation to power, as a marker of an individual owner’s existence in a specific time and place.

At this holiday season, when we are called to awareness of past, present, and future, I think it’s worthwhile to consider a Book of Hours as offering possible insights as to how content survives. In a Book of Hours, while there were some standard content inclusions, there was also a certain customization. There would always be inclusions of a calendar of Feasts and saint’s days as well as the Hours of the Virgin, but there was a surprising variety of other material that might be added in upon request of the patron commissioning such a work (such as prayers to a locally favored saint). While there were standard subjects for illustrations (the Annunciation, the Nativity, etc.), those too were customizable, according to the whim of the patron, an artist, or practices of a specific geographical region. Those illustrations served as navigational aids to the user in locating a particular place in a volume lacking a table of contents or page numbers. Or they might act as visual indicators of meaning, as when a miniature rendition of an ox might be used to suggest the Gospel of Luke as the source of a particular passage.

There was a certain flexibility as to length of the passages included. A Book of Hours might include only an opening verse of canticle or Psalm, assuming that the user would be able to recall to memory the full text of a frequently heard portion of Scripture. (The 21st century is not the only age where brevity is deemed a virtue.)

In the collections of libraries and archives, the numerous instances of damaged pages with cut pieces removed or volumes with missing pages suggests that over time, only some portions of the content retained value. (See this wonderful series of videos from the librarians at the University of Iowa.)

Of course, as time passed, these volumes became the prize of collectors or the domain of the scholar. The artifact would be used in far different ways; historians might look at the visual elements of the calendar to see when and how certain annual tasks were performed or viewed. The value of the Book was centered less around its original intended use and more around the probative evidence it supplied.

Having dealt with the past and the present, how do these volumes then turn us to the future? As I see it, Books of Hours are an exemplary mix of interface and content, customizable, flexible and in so many instances, artistic output worthy of preservation. It may just be me, but in the closing days of 2015, as I view such remarkable items held perhaps in the collection of the Morgan Library or as part some other library’s special collection, I heartily believe that the Book of Hours offers lessons to developers and content providers. Centuries later, such beauty and utility still fascinate and engage us, while evoking a larger temporal connection to centuries of human behavior, belief and care. The book is not dead, neither as container nor as document, not as long as we can be inspired by such masters. As you enter into the New Year, give a thought to providing your users with the same sense of wonder and delight. When they pick up their reading device, do they linger? Does its design and beauty compel attention?

Discussion

1 Thought on "Past, Present and Future: The Book (of Hours)"

Many of the traditions of this form of publishing can still be seen in faith-based publishing and there has been an explosion of apps in this area that not promoted by the app stores or discussed much in the publishing press. There are many one person app operations but also you can see it in apps from more mainstream players such as the Church of England and the Catholic Church.

For example the suite of Church of England apps include apps that not only have daily content but content that is presented depending on the time of day and can support variations based user preferences. I’d suggest that that lessons might already be being learnt (https://www.chpublishing.co.uk/apps).

As part of the company that develops these apps (as well as someone active in academic publishing as a UP board member for University of Wales Press and helping Goldsmiths set up a UP) I think that we will be seeing more and more of visual and customisable publications that the history of the Book of Hours provides inspiration for.