For years, journalists covering scholarly publishing have relied upon a standard formula that has become a cliché. It goes something like this:

- There is a crisis in scholarly communication. Libraries can no longer purchase everything their readers want. Quote angry academic. Quote Harvard University Librarian. Quote SPARC.

- The cause of the crisis is publisher greed. Cite Reed-Elsevier profits.

- Invoke savior: Open Access publishing, free repositories, publish then review, overlay journals, illegal sharing…etc.

- What’s preventing resolution? Tenure committees, funders, publishers working for their own interest.

- Last, appeal to social activism: We have to work together. No one can do it alone.

This formula makes for a great story: There are victims — librarians, needy scholars, a mother with a sick child. There is a villain — the greedy publisher. There is a hero — usually a graduate student or idealistic young professor willing to take a risk and do what is right. And there is a call to transform moral outrage into action — refuse to review for Elsevier, put your papers in a free repository, pay for open access publishing, steal from the rich and give to the poor.

This narrative doesn’t capture the complexity of the scholarly publishing market, but complexity just confuses a good story. There are too many actors, too many plot lines. Characters are complicated. Our hero is flawed. This realistic narrative cannot be put into a 30 second film trailer that begins with “In a world…”

There is a counter-narrative to this victim-hero story, but its not frequently invoked, and the evidence to support it has been made very difficult to acquire. This is the narrative of the library being slowly starved by its parent institution, and it is much harder movie to watch, because it is a story of long-term neglect. Nevertheless, if you look at the data, its clear that libraries have been receiving a declining share of their institutions’ expenditures.

Regrettably, the Association of Research Libraries (ARL) has not updated this graph since 2011 and they have no intention to do so in the future. I know because I’ve asked twice. Now, it is possible to recreate the graph, but it requires a lot of work and it is unlikely that we would find out anything new. Each year, libraries receive a smaller slice of their institution’s pie.

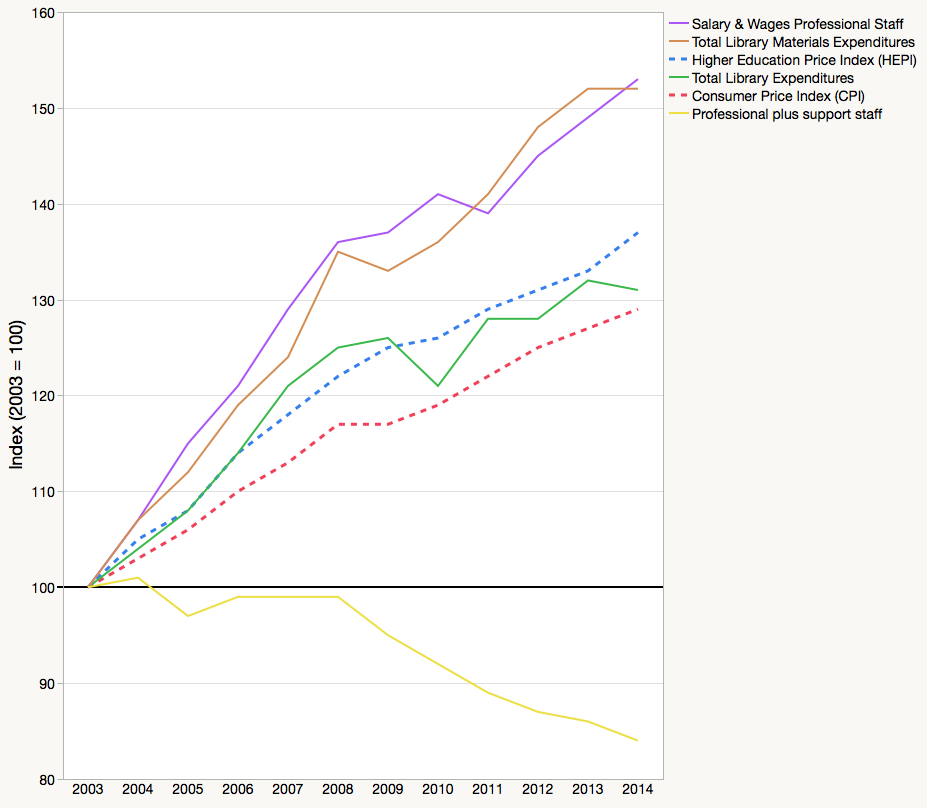

ARL is still producing some statistics for public consumption, the most popular of which is the Library Investment Index, often referred to as the “ARL Ranking.” The ARL Ranking, like the US News & World Report’s college rankings, is a composite index based on several library metrics: Total Library Expenditures, Salaries & Wages Professional Staff, Total Library Materials Expenditures, and Professional plus Support Staff.

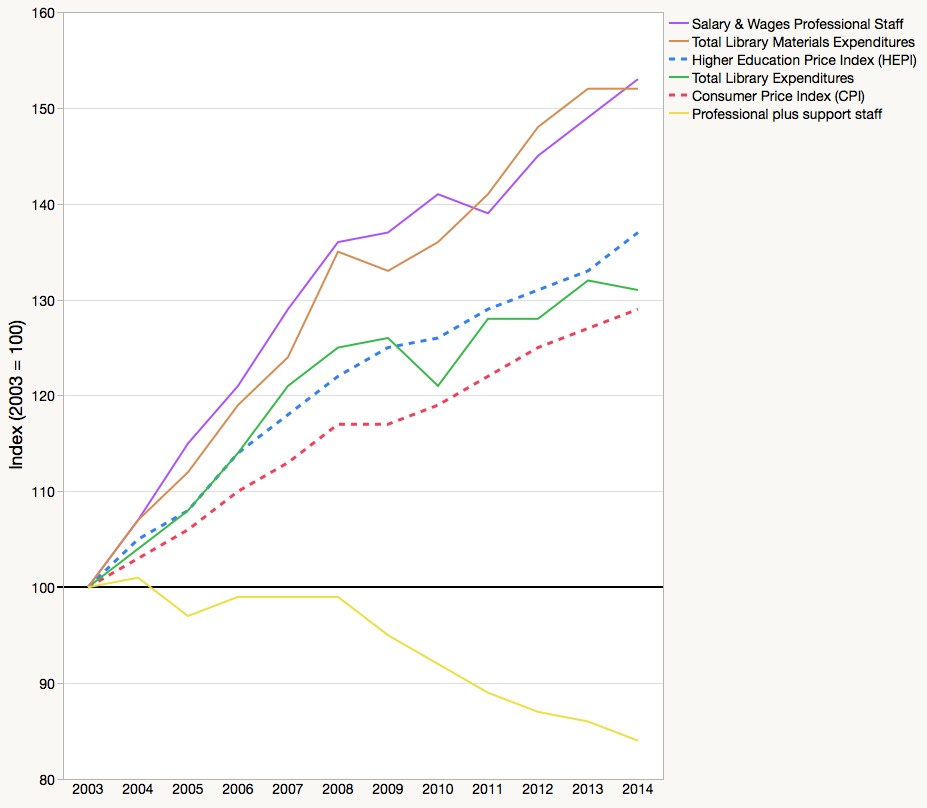

In the following plot, I take the Library Investment Index and convert each of the component metrics into an index, where 2003 = 100, so that we can compare their performances over time. I also include two comparison indexes, the Consumer Price Index (CPI), a favorite comparison tool for ARL, albeit inappropriate and misleading, and the Higher Education Price Index (HEPI), an index that more closely approximates the true cost of higher education.

As you can see, total library expenditures of 115 ARL member institutions (green line) has continuously outstripped general inflation, as measured by the CPI, but has been more in line with HEPI, rising about 31% since 2003. Not surprisingly, Total Library Materials Expenditures (gold line) has also outpaced both inflationary indexes. The median ARL library spent 52% more on library materials in 2014 than in 2003. Not surprising either is the Salary & Wages of Professional Staff (purple line), which increased 53% since 2003 and is now 24% higher than general inflation. Unlike other countries, academic librarians in the United States benefit from employment protection, either through institutional tenure or similar academic status. As Stanley Wilder wrote in his ARL report on demographics “librarians in the U.S. are unusually old and aging rapidly.”

The really interesting and novel trend that no one seems to be discussing is that libraries have been shedding staff, especially since the great US housing recession (yellow line). While both professional and support staff are included in this one line, my memory of this event — at least at Cornell — was that libraries purged themselves of many support staff while providing financial incentives for older professional staff to retire. Whatever strategy was used in each ARL institution, the pattern is very clear: The number of staff at ARL libraries has dropped by 15%, from a median of 204 staff in 2008 to 173 in 2014.

So what stories do these data provide us?

One could argue that libraries are doing a very good job containing costs (green line) in an institution where other costs are skyrocketing. One may also argue that research libraries are spending an increasing share of their budget on collections (gold line), where most readers want their budgets to be spent. Or, one may take a cynic’s view and argue that whereas libraries are becoming more efficient (supporting fewer staff), they are spending much more money on an aging cohort of baby boomers who refuse to retire, preventing a newer crop of librarians from entering the profession.

I realize that this last statement is going to result in a lot of angry comments and personal hate mail, but I should remind readers that the same demographic and economic phenomenon affects US professors similarly and that Cornell University employs some of the oldest tenured faculty in the nation.

The problems affecting libraries and professors are the same problems affecting many other institutions that depend upon highly trained professionals — they cost a lot to recruit, train, and retain. And once in the organization, we like to reward these professionals based on experience and seniority. Unfortunately, these individuals don’t get any more productive as they age — a professor in 2016 is no more productive than a professor in 1966 — meaning that they get much more expensive over time. Unless we believe that we should index professors and librarians salaries to the CPI, we’re going to have to accept that professional costs are going to be difficult, if not impossible, to contain.

Library materials represent a tiny percent of overall institutional expenditures. An outsider may be surprised at how much fuss is made over such a small slice of the institution’s pie. But libraries are still perceived as a core function of the institution, standing as beloved architectural statements of their historic value. Perhaps this is why no one wishes to take responsibility, at least in part, for their financial neglect. It’s much simpler to blame someone else.

A crisis requires a frame of liability and accountability. Someone or something is always to blame, and if it is not apparent, a convenient scapegoat is used as a surrogate. It is much more difficult to talk about systemic problems in an organization – why there are barriers to information flow, why some organizations are underfunded and understaffed, or how well-intended policies and laws create unintended consequences. These complex stories are much more realistic but they never seem to satisfy our psychological need for accountability and closure.

Perhaps this is why the crisis in scholarly communication — a narrative that began in the 1920s — continues to be told today. It makes a darn good story.

Discussion

19 Thoughts on "Library Expenditures, Salaries Outstrip Inflation"

The “graying” of academia could be a topic all its own. Similar trends are occurring in research, as this video summary of the age distribution of NIH PIs and medical school faculty shows:

This trend is also covered with some speculation as to the reasons this is happening (https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/blog/2015/04/r01-teams-and-grantee-age-trends-grant-funding), which includes the notion that senior faculty are hanging on longer, adding themselves to grant proposals, and almost colluding with one another (“. . . when R21s are submitted as multiple-principal-investigator applications, the principal investigators tend to be contemporaries of each other”).

In libraries, we have young librarians and younger support staff interested in libraries being shut out by high salaries for older staff in tenured/secure positions. In research, we have younger researchers shut out of research funding by older researchers coordinating to some extent to hold on longer. Yet endowments at these institutions are often built up to high levels based on the ill-defined notion of “generational equity.” These trends don’t seem equitable to the next generation.

Add to both the lack of overall funding (every major US government research funding level is below 2012 levels adjusted for inflation today, except for the DOE; libraries are receiving about half of the share of university budgets they received 30 years ago despite huge increases in tuitions and fees), and you can see why we have a problem. It’s not a crisis (that requires a tracheotomy or a defibrillator), but it is a problem. And problems can be solved rationally and systematically.

Where do publishers fit into this? From what the data show (http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2016/03/10/revisiting-have-journal-prices-really-increased-much-in-the-digital-age/), publishers have been absorbing a huge increase in outputs (from China and the major research markets) while increasing our per-serial prices very little (9% or less indexed to 1990 and adjusted for inflation). The problem now facing many smaller, independent publishers is that they are literally paying the price for conservative price increases — the 9% increase is far below the CPI increase during the same period (CPI increased 68% during the same period). The cost containment at publishers looks unsustainable, and concerns are growing.

It is a complex narrative, but the theme is simple — funding for libraries and research is inadequate. I think we might all be able to rally behind that.

The US Military addressed the long in the tooth problem years ago with mandatory retirement age requirements. This allows younger folks to advance and keeps new ideas flowing.

hahaha Thanks Phil, will consider this today at my union meeting! As Research Coordinator I belong to same union as library staff. The Librarians are in a different one. Can’t we all just get along? 🙂

The federal law that allowed universities to mandate retirement of faculty by age 70 probably should have been continued past 1994. (Kudos, Phil, for treating “data” as a plural noun.)

“…librarians in the U.S. are unusually old and aging rapidly”

As an “unusually old and aging” librarian myself, I wasn’t aware we aged any more quickly than the rest of the population (:

The key to understanding the sentence quoted here is that it refers to librarians as a group. Groups don’t age the way individuals– they can get younger or older, quickly or slowly. You’d expect the age of a professional group like “librarians” to remain stable over time. The fact that the age of librarians has been increasing is worth investigating.

Trust me, Older librarians have better work ethics and from my perspective as productive as our “younger colleagues”. Furthermore if we could afford to retire – we would! Given lower salaries for years and State budget cuts, I believe you are missing key elements in your analysis as quoted and noted above funding for content and research is very limited for institutions – I can rarely acquire content without giving up content it is a constant juggle of budgets. It is misguided analysis like yours and definitively; a bias to publishers that does not value age and perspective – Lets hope you don’t find yourself in a position of “unusually old and aging rapidly” with little to no means to retire with adequate funds.

Academic librarians without faculty status/tenure do not enjoy any protected employment status. I have worked for over a decade in a large research university’s library and I could be fired tomorrow (just one reason I don’t post on the Internet under my real name).

Also, one reason that some older librarians are moved out under the guise of early retirement is because they are, either in perception or reality, unwilling/unable to embrace the huge changes in mission and services that academic libraries have undergone in the past ten years.

I’m reminded of the old story that God appeared in a dream one night to a university librarian. The librarian was given the opportunity to ask 3 questions:

Question 1: will the library ever be fully appreciated by the faculty at my institution?

Answer: Not in your lifetime.

Question 2: will the Cubs ever win the World Series?

Answer: Not in your lifetime.

Question 3: will the crisis in scholarly communications ever end?

Answer: Not in my lifetime.

As John Adams said, “Facts are stubborn things.” Your facts nicely show library budgets are keeping up with inflation, at least as far as measured by the CPI and the HEPI. However, I wish you would add a graph of (normalized) number of publications. Are libraries keeping up with “content inflation,” providing scholars with the same proportion of available scholarly content? That might explain the apparent shift to fewer, presumably more skilled, workers and more materials expenditures.

ARL publishes a graph that includes serial and monograph expenditures and also the number of monographs purchased, but it does not include a line with the number of subscribed serials (see: http://www.arl.org/storage/documents/monograph-serial-costs.pdf). Since libraries purchase many/most of their journals as Big Deals, it makes a lot less sense for the library to track individual titles. I don’t think anyone argues that they have access to fewer titles. The debate seems to be focused around price.

“…they are spending much more money on an aging cohort of baby boomers who refuse to retire, preventing a newer crop of librarians from entering the profession.”

This is just not true! The ARL data are very clear in saying that the percentage of the population remaining in place after age 65 has been rock solid since 1986, with only the slightest rise between 2005 and 2010. There is no “refusing to leave” going on here.

There is a better explanation for the rise in median compensation levels in ARL libraries: the rise of non-traditional professionals. I have been documenting this phenomenon for many years. People with computing, financial, fundraising, human resources skills (for example) routinely cost more money for less experience than those with a traditional librarian skill base. Demand for non-traditional skills has been skyrocketing, with no end in sight.

This phenomenon goes hand in hand with the general decline in lower skill functions in research libraries. Both points I make in this short article in LJ:

Thanks for your contributions, Stanley. I accept that 65+ librarians may be retiring at the same rate as earlier cohorts; however, the overall age profile of librarians has been getting progressively older, as your figure illustrates. Since we compensate librarians based on their status, experience, and seniority, the same number of librarians is getting more expensive to support year over year.

Upon further consideration, it does look like the percentage of population 65+ is indeed increasing in the last two surveys. From your figure, the percentage of librarians aged 65+ from the 2005 cohort looks about 1 full point above the 2000 cohort; and the percentage of 65+ from the 2010 cohort looks about 2 additional points above 2005. I think this suggests that as the baby boomers shift forward, they are claiming more 65+ positions.

A few thoughts from reading this piece …..

It reminded me of the Wikipedia piece on the Serials crisis:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serials_crisis

Albert Henderson used to argue that universities do not fund libraries adequately:

http://users.ecs.soton.ac.uk/harnad/Hypermail/Amsci/3555.html

Given the article level of access Sci-Hub provides these days, the ‘article’ may be a more important unit rather than the journal in the future:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sci-Hub

As for salaries and inflation, I would suggest using the ARL Salary Survey rather than the ARL Statistics — the salary survey collects individual level salaries rather than institutional level aggregated expenditures. The latest ARL Annual Salary Survey open access volume is here:

http://www.libqual.org/documents/admin/2012/ARL_Stats/2005-06ss.pdf

And for those who subscribe to the most recent pdf, see here:

http://publications.arl.org/ARL-Annual-Salary-Survey-2014-2015/

And here’s the trend line on prof plus support staff for a longer time period:

http://marthakyrillidou.com/professional-plus-support-staff-arl-libraries-century/

All the best, Martha

I still argue that universities are failing their libraries, including their librarians, faculties, researchers, students, and the sources of their R&D grants. Provosts and other managers happily take R&D money, which doubles exponentially every 15 years or so (adjusted for inflation), but they shirk any responsibility for “the conservation of knowledge” (Vannever Bush’s phrase). Instead they have cut library spending since 1970, increased profitability, and sent the ARL spinning a curious and insubstantial web to deflect blame.

Were I in charge of science policy, I would demand that academic contractors use their enormous grant overhead (averaging 55 points) to keep their libraries up to date on all relevant publishing.

Ironically, I think that one source of the energy behind the hero-victim narrative is that librarians are starting to see that we are far from virtuous victims in the current situation. Putting aside the macro question of whether the academy pays too much, just enough, or not enough to support scholarly communication, it’s completely clear that some libraries are paying too much: http://www.pnas.org/content/111/26/9425 If I were a university provost, I would not invest more money in a library that paid multiple times what another library paid for the same journal bundle. As a library administrator, I could not assure that provost that we got the best possible deal, because very probably we didn’t. The information asymmetry between libraries and publishers inherent in the bundle model almost guarantees a bad deal (from the library’s perspective).