Note: Lydia Porter, an office assistant in the J. Willard Marriott Library at the University of Utah, was instrumental in gathering and collating the data cited in this study, and her expert help is gratefully acknowledged. The full data set on which this discussion is based can be seen here; for a manipulable copy of the original spreadsheet, please contact the author.

In late 2010, I was thinking quite a bit about book use in research libraries. The conventional wisdom was that “no one uses print books anymore” in libraries like mine, and indeed annual data provided by the Association of Research Libraries (ARL) showed a pretty clear decline in book circulations: between 1991 and 2008 (the most recent data available at that time), the number of initial circulations in ARL libraries had fallen by over a quarter. And when I ventured into the book stacks in my own library I usually found them spookily deserted.

But I was haunted by a passing comment a colleague had made to me a few years earlier, noting that the conclusions we draw from library usage data can easily be confounded by changes in the library’s user population. It occurred to me that if we really want to understand what’s happening with regard to library patrons and printed books, we need to take into account the changing nature of our patron base. And the simplest and most consistent change in that population is growth over time: university enrollment tends to grow from year to year.

The question I decided to examine, then, was: how much of the change in individual patron behavior is being hidden by raw circulation data? Clearly, if the size of your patron base is growing while circulation numbers remain the same, that means that the average patron is using the printed collection less; and if the circulation numbers are actually falling while your patron base is growing, that means the average patron is using the library at a more steeply-declining rate than the circulation data suggest.

The way to answer this question is simple, but not easy: you track circulation data for a library along with changes to the size of the patron population, dividing the number of circs by the number of patrons, and watch for trends over time. It’s not a particularly challenging statistical task, but gathering the data for a large number of libraries is a lot of work.

So for several months I spent part of each day gathering circulation and enrollment data for each of the 114 ARL member libraries from the ARL Statistics database. I examined the years 1995-2008, calculating two figures for that period for each library: the total change in raw circulation (number of initial circs), and the change in circulation rate (number of circs per full-time student). I counted only initial circulations rather than total circulations (in order to exclude renewal transactions from the calculation, since the point of the study was to measure how many times the books were used, rather than how intensively). I used enrollment as a proxy for “patron base,” even though I recognize that faculty, staff, and community patrons check out books from the library as well. Since these other populations remain relatively constant in size, and since I was more interested in tracking the shape of the change curve than in knowing its exact distance above the X axis, this seemed like a good compromise.

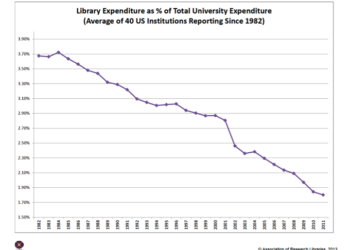

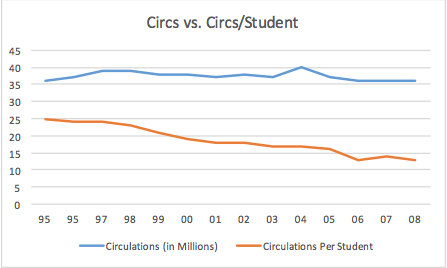

What I found was sobering: on an aggregate basis, ARL libraries had seen a fairly steady number of initial circulation transactions between 1995 and 2008, with totals hovering between 36 and 40 million. However, during that same period the aggregate circulation rate fell by almost 50% (Figure 1)—a significant change in patron behavior, and one entirely masked by the raw circulation trend.

Perhaps just as interesting as the aggregate numbers was the variation in results by institution. While the great majority of ARL libraries had seen declines in both circulation numbers and circulation rates during the 1995-2008, in some cases the difference between raw number and rate was very dramatic and in others it was less so — and a handful of libraries had actually seen an increase in both.

What came next was, for me, even more interesting: I had a great deal of trouble getting my study published. I submitted it to a journal with a particular interest in collection development in research libraries, and it was rejected. Then I submitted it to a journal focused on library management; no luck there either. I eventually decided to submit it in an abridged version to a less formal venue, and the report was published in Library Journal under the title “Print on the Margins: Circulation Trends in Major Research Libraries.” The data set was too large to embed into the article, so I pulled out a few noteworthy institutional examples and provided a link to the full data set for those wanting to investigate further.

That piece was published in mid-2011, and over the past couple of years I’ve been feeling a growing sense that it was time to revisit the ARL data and see what’s happened in research libraries since. So, with the able and gracious assistance of my colleague Lydia Porter, I gathered and analyzed the circulation and enrollment data for the years 2008-2015 (the most recent data currently available).

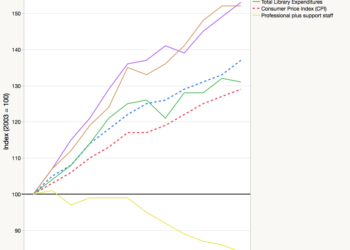

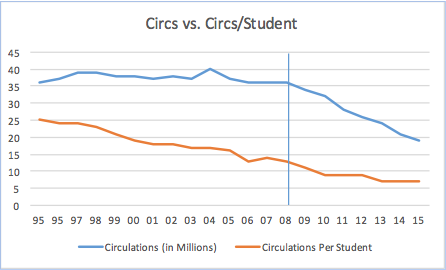

The results (Figure 2) are very interesting. A couple of noteworthy things have happened since the last time I looked at the data:

- In 2009, what had been a fairly steady state in initial circulations between 1995 changed dramatically, and there has been a hard and steady decline ever since. Between 2009 and 2015, total initial circulations in ARL libraries fell by almost half (from 36 million to 19 million).

- During that same period, the decline in circulations per student has continued as well, though the rate of decline has slowed. In fact, the average number of initial circulations per student has stayed the same (at 7) for the past three years, suggesting that the decline may have bottomed out.

What does all of this mean? I would suggest the following take-aways:

- Aggregate data are interesting, but for any individual library, what matters most is the trend at that particular institution. Interested readers from ARL libraries are encouraged to consult the data set and see what the trend lines look like for their own organizations.

- As I pointed out in my original article, it’s important not to assume that declining circulation rates mean declining use of library resources overall, or decreasing engagement with library services. For example, a library that offers an increasing proportion of its information resources online should naturally expect to see a decline in the circulation of printed books — especially if there’s significant overlap in content across formats.

- That being said, any library that is seeing a steep decline in the use of its print collection should probably let that trend inform a serious examination of its space and budget allocations. (And given that the average decline in circulations per student since 1995 has been so dramatic — from 25 to 7, a 72% decrease — there are lots of research libraries seeing steep declines.)

- For book publishers, these numbers have significance to the degree that print book sales to libraries matter to them. Those sales may matter less today than they once did, but even so, it’s probably worthwhile for scholarly book publishers to keep an eye on this trend.

In closing, I want to acknowledge some of the obvious limitations of this data set: it reflects trends only in large North American research libraries, and will have limited relevance (for example) to college libraries in North America and to research libraries in other global regions. Also, by measuring initial circulations only, this study ignores changing patterns in in-house use of books. (Other libraries’ mileage will certainly vary, but at my institution the reshelving of books has declined even more precipitously than circulations, leading me to believe that in-house use of books is falling as well.) My hope is that the data provided here will prompt further examination of relevant data in other areas.

Discussion

45 Thoughts on "Less Than Meets the Eye: Print Book Use Is Falling Faster in Research Libraries"

I work in a university Writing Center and the dominating trend of first-year assignments we see are argument papers discussing current issues. The desire to get students engaged with their world may naturally turn students away from using a books as a source due to their not-so-up-to-the-minute nature. With the prevalent use of technology in the classroom, the average student finds their research online, sometimes, but rarely, in journal articles but mostly web articles. Outside of humanities majors (mainly English) the assignments seem geared toward internet-based research. We get far more “how do you cite a website” than “how do you cite a book.” Those first-year writing assignments can set a trend for how a student uses resources throughout their entire college career.

WHO IS DOING THE READING?

Sorry, but in an academic sense, all members of a university community are not equal, and that should be taken into account when evaluating data, such as those presented in Rick Anderson’s interesting piece. Simply stated, assuming the general good is the aim, is a book read by 100 Princeton students more deserving of a place on the shelves than one book that no student read, but that helped Einstein through a critical stage of his thinking? Yes, he could have got it through interlibrary loan, but his time is more precious than a student’s, and he needed it quickly for an unbroken chain of thought.

Is this dataset available as a .csv or .xls file rather than a PDF?

Yes — email me at rick.anderson@utah.edu and I’ll be happy to send you the source .xls file.

Interesting study. Thanks. I have a few questions for further research:

1. I wonder how much of enrollment growth represents students taking online courses or in online programs? Physical books from the home library may be less accessible to them that to resident students on campus.

2. I wonder if it is possible to compare the variation between institutions to collection strategy. Has circulation of print books fallen most at institutions that have moved more aggressively to collect or make accessible e-books? If so, which came first?

3. Finally, I would love to see someone repeat this study with a very different set of libraries — the Oberlin Group of liberal arts college libraries. Do we see the same pattern?

Thanks, Jonathan — these are good questions. I particularly agree that it would be very interesting to see this same study replicated with other types of libraries.

I’d like to see statistics showing interlibrary loans during the same period.

Assignments which allow students to mine online material for evidence to paste into papers will naturally result in a decreasing checkout of print materials. Come on, professors, let your students read!

Lacy, Meghan. (2014). The slow book revolution : creating a new culture of reading on college campuses and beyond. Santa Barbara, CA : Libraries Unlimited, 2014.

I agree with Donald’s comment about the user base. When I was an academic librarian, we had three main user bases: students, faculty, and the general public (we were open to the public to use our resources). A research library should be able to provide resources/support not just for students, but the faculty conducting research as well.

Another consideration is usage of print library materials that are not circulated. Often reference or other books are not checked out but used by students and faculty during their visit to the library. Some libraries may have tried to keep some statistics regarding this, but often is too difficult to try to track.

I have seen many academic libraries cut their print budget and purchase more ebooks. It can sometimes be cheaper to make a purchase agreement for online content than ordering print versions (it really depends on the deal made by the vendor or if in a consortium). This cut is not due to the actual wishes of their users, but usually necessary due to slashed budgets. I have had many a disappointed student who didn’t want to read the ebook but wanted to access the print version. In my experience, the younger students still want to have access to the print version of the book and will only choose an ebook if in a bind. I do agree that this does vary from institution to institution.

I agree with Heather and I see the same thing happening at my university.

I would add that in the STEM fields, the quality of the books has gone downhill. Most non-textbooks coming out of the major publishers (Springer, Elsevier, T&F) are collections are largely unrelated papers. I can’t justify spending several hundred dollars on a book when the same content is available as a journal article. Faculty often have an interest in these titles, but there is far less interest by the students*.

* I would guess that this has to do with their specific topic not being in the book title. If a student is doing research on Bill Clinton, a book specifically on him will catch the eye before a general book on American presidents. Also, catalog records that do not reflect the content are a major issue.

Catalog records not reflecting content are indeed a problem! A library at which I worked once purchased a package of very good e-books on art history, and they all had the same single subject heading – “Art.” A biography of Carvaggio? Art. A book on Dadaism? Art. Brutalist architecture? Art. Our catalogers had to re-catalog the whole bunch.

When a freshmen I went to the library not so much to study or check out a book, but rather to check out the co-eds! So the question in my mind is is dating declining concomitantly with readership?

It would be interesting to see [undergrads vs grad students vs faculty] and [top rank vs lower rank universities, e.g. Ivy League vs SEC] and subject areas [math, hums, science, engineering] for a few cases to see if it would make any difference

If circulation per student is declining as the student body grows, that doesn’t necessarily mean they want to read print books less – it’s symptomatic of the long tail. The relatively small proportion of your print books that are circulating regularly can still only be checked out to one person at a time, so circulation will remain steady as enrollment increases. It’s not the case that more students should equate to more books being circulated – if the books they want are already checked out, they’re not necessarily going to check out other books instead. So, what is perhaps also worth taking note of is that user satisfaction with regards to the print collection may decline as competition for a limited collection increases. (This is certainly true of anything resembling a textbook.) The same is not necessarily true when it comes to ebooks, at least the ones that permit more than one simultaneous user.

Good thoughts, Hilary, thanks. I agree that it would be inappropriate to conclude from the data I’ve provided that students have less desire to read printed books — but I think it would be equally careless to conclude that circulation is going down because students are going away frustrated when the book they want is checked out. Either of those conclusions would require evidence that the data in hand can’t provide.

Agreed! I do think that Jonathan Miller’s first point, above, is likely also in play – not only in terms of online education students who aren’t physically able to access our print collection, but in terms of students expecting to access the resources they need from wherever they are. Because some libraries have been favoring electronic over print in terms of new book purchases for quite some time, in order to meet those students’ expectations as well as rebalance physical space allocation, our print collections are becoming less current, which probably also accounts for some of the circulation decline. (You mention the e-preferred model in terms of proportions of the collection but not in terms of relevance/currency of the collection.)

Re: declining currency of the print collection — I think this is a real thing, and certainly a greater or lesser factor depending on a given library’s collecting preference for ebooks. But I think it’s also important to point out that the decline in print circulation has been happening since at least 1991, long before ebooks became a factor in library collecting. (I do suspect, however, that the steep drop-off in print circs since 1998 is at least partly due to large-scale library adoption of ebooks.)

As you looked at this data, did you feel confident that “initial circulations” was reliably enough reported between institutions, and for each institution between years, average without some kind of accommodation for outliers? For 2015, circs range between 2 and 30 uses (in some years the range is much greater). Do users at different institutions differ that much in their use of print resources? Or what about the library whose last 4 years of data were 5, 61, 3, 7?

Hi, Kristin —

As with any data set this large and diverse, there are definitely outliers, some of which, I’m sure, are artifacts of reporting weirdness. I do feel confident that the data set as a whole shows us something real that is happening in ARL libraries overall. But I’ll take this opportunity to reiterate that no librarian should assume that the aggregate data tells him or her much about what’s happening in his or her own library — that’s another reason I provided the entire data set. Any ARL librarian can look at it and see what the trend line looks like in his or her own institution, while (of course) taking into account how confident he or she is in the integrity of the data they report to ARL.

I’d hazard the guess that schools with larger graduate student populations in the liberal arts would have greater circ and rate numbers than schools without. Is there a way of testing this hypothesis with the data available?

I’d also hazard the guess that there is some correlation between the rise of ebook collections like netLibrary and Project Muse and the decline of print book circulation.

I’d like to echo the comments of DZRLIB and others who would like to see a similar table with faculty circulation numbers, and in particular, I’d like to see this overlaid with numbers for the breakdown of TT vs. adjunct faculty for each institution/year.

But, keeping the focus on student circulation for the moment: I wonder if the libraries would be willing or able to supplement this existing data for 1995-2015 with either (a) the year in which their campus adopted an online course management system (or e-reserves or VLEs) where library readings could be uploaded electronically by instructors, or, better yet, (b) the proportion of courses offered in a given year that actually took advantage of such CMSs. In other words, I’m wondering how the widespread adoption of these technologies at a given campus might correlate, or not, with declining print circulation to students.

I’d like to echo the comments of DZRLIB and others who would like to see a similar table with faculty circulation numbers, and in particular, I’d like to see this overlaid with numbers for the breakdown of TT vs. adjunct faculty for each institution/year.

Boy, I think all of us would like to see that data. Unfortunately, I’m not aware of any large research libraries that track faculty circulation separate from student circulation — on most campuses, I think that would entail cost and effort way out of proportion to the benefit it would yield. (If that is indeed happening somewhere, I’d be very interested to hear about it.)

I wonder if the libraries would be willing or able to supplement this existing data for 1995-2015 with either (a) the year in which their campus adopted an online course management system (or e-reserves or VLEs) where library readings could be uploaded electronically by instructors, or, better yet, (b) the proportion of courses offered in a given year that actually took advantage of such CMSs.

Since the ARL statistics count initial circulations rather than the number of items circulated, I’m sure that the advent of online course reserves has had a significant impact on circulation numbers — though not one that would account for a steady decline in circs per student over the course of 15 years.

Have you taken into account the situations where not much has been purchased in print? The e-books tend not to have circulation statistics and the print books held are just getting older and older …

We’ve been avoiding the purchase of print for at least a dozen years now.

Perhaps the trouble that the author encountered getting this study published in a journal was because the statistical calculations are too back-of-the-envelope to tell us much. Anderson says that “It’s not a particularly challenging statistical task,” but in fact it is challenging and his overly simplified the model has led to some faulty conclusions.

1) The transition from print journal collections to online journal collections happened starting around 1998 (the point in time when Internet browsers started to be common). In the late 1990s, many libraries circulated print journals for short time periods resulting in very high circulation numbers. The sharp drop in circulation in the late 1990s almost certainly represents a decline in circulation of print journals as libraries shifted to bundled online journal subscriptions. Data that doesn’t distinguish between bound journal circulation and book circulation doesn’t tell us much about book circulation.

2) Most libraries have shifted funds to electronic books. Some of the decline in circulation is certainly an artifact of just buying fewer print books in the first place.

3) Except for a few classics, newer books typically circulate at a greater rate than older books (the reason public libraries stock up on bestsellers). If libraries are buying fewer new print books, than circulation statistics are slanted towards a backfile of aging books which would predictably circulate at lower rates.

4) The data do not show a “hard and steady decline” but rather a curve that seems to have reached a “knee” when reading habits adjusted to two major disruptions— 1. a shift to online journals (knee around 2007/8) and 2. the widespread availability of ebooks (knee around 2012-13). It seems like instead of conducting “a serious examination of space and budget allocation” libraries with a decline in circulation would be well advised to do more work examining the role of print in hybrid collections. Which print materials are students are using? Why they are choosing print?

5) Figure 2 indicates that despite circulation declines students may actually have a preference for print. The overall number of circulations is declining, while circulation/student is holding steady. That suggests a possibility that students may be selectively using print resources from a increasingly smaller pool of options.

I would suggest the following takeaway:

Predictions of the future paperless library were wrong. Even though students have a clear and strong preference for online journal articles, they are still using significant numbers of print books in academic libraries. Libraries should seek to maximize the value of print expenditure and space allocation by better understanding the role of print in hybrid collections and writing collection development policies that define how format is relevant in purchasing decisions.

Hi, Amy –

Well, I have to say that it took you longer to comment than I expected.

Most of the points you’re making here (that print-to-online shifts have contributed to the dramatic drop in circulation, that newer print books circulate more than older print books, etc.) have been discussed in the comments above. I don’t feel the need to belabor that discussion further, except to say (again) that these are among the reasons I have not suggested that usage of library collections is declining – only that circulation of print materials is declining, and has done so precipitously over the past two decades. Your response doesn’t actually amount to a critique of my statistics; you’re just offering a few of many possible interpretations of the data. (I’d be interested in seeing any supporting evidence that you might have for those interpretations, by the way.)

And by the way, those data most certainly do show a “hard and steady decline” in the number of initial circulations annually since 2009: as I pointed out (and the data clearly show), initial circs in ARL libraries fell by half over the six-year period 2009-2015, and they fell at a remarkably steady rate year over year.

Amy makes an excellent point in that “Even though students have a clear and strong preference for online journal articles, they are still using significant numbers of print books in academic libraries.”

A point that I’m confident no one would dispute, particularly since “significant numbers” is a nice, fuzzy term.

Agreed … but from what we hear from some students, it is much easier to work with several print copies of books than switching laptop screens. Perhaps it’s a STEM thing?

I don’t understand your use of the word “but.” No one is disputing that print books are more convenient than ebooks in some contexts, just as ebooks are more convenient than print books in others. No one is disputing that students still use print books, or even that they use them in “significant numbers.” The reality of the downward trend in book use is not the same thing as a claim that no one is using books anymore.

Tuoche!! … but I continue to be concerned about the use of these statistics by ‘papeless library’ adherents … who do not take into account the need for faculty/grad student data; data on subject groupings (especially math and humanities); as well as a unambiguous definition of ‘book’ (which should not include collections of conference papers & edited monographs).

I’m not sure who the “‘paperless library’ adherents” are. Can you tell us, and maybe cite some of their arguments?

“The bookless or paperless library is also something that is key within academic institutions. For example, it was announced last year by London’s Imperial College, that over 98% of its journal collections were digital and that it had even stopped buying print textbooks!”

http://www.bbc.com/news/business-22160990

=========================

“The Stanford Digital Library Technologies Project, which ended in 2004 was one participant in the DLI2, Digital Library Initiative Phase II. The project, began in 1999 supported by several government, university, corporate sponsors.

The goal of this Project was to design and implement the infrastructure and services needed for collaboratively creating, disseminating, sharing and managing information in a digital library context.”

For a history of the project please visit: http://diglib.stanford.edu:8091/diglib/

============================

“UC Berkeley’s Digital Library Project

For digital libraries to succeed, we must abandon the traditional notion of “library” altogether. The reason is as follows: The digital “library” will be a collection of distributed information services; producers of material will make it available, and consumers will find it and use it, perhaps through the help of automated agents. Libraries in the traditional sense are nowhere to be found in this model.”

Communications of the ACM (1995), 38(4), 59-60

======================================

“A Truly Bookless Library

The new engineering and technology library at U. of Texas at San Antonio holds no printed volumes — a realization of a goal many libraries have set as a vision for the future.

The idea of a libraries with no bound books has been a recurring theme in conversations about the future of academe for a long time, and it has become common practice for academic libraries to store rarely used volumes in off-campus facilities. But there are few, if any, examples of libraries that actually have zero bound books in them.

Some libraries, such as the main one at the University of California at Merced, and the engineering library at Stanford University, have drastically reduced the number of print volumes they keep in the actual library building, choosing to focus on beefing up their electronic resources. In fact, some overenthusiastic headlinewriters at one point dubbed Stanford’s library “bookless.” But that is “a vision statement, not a point of fact,” says Andrew Herkovic, the director of communications for Stanford’s libraries.”

https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2010/09/17/libraries

See also: http://www.papersave.com/blog/the-first-paperless-library-shows-the-advantages-of-technology/

So this is interesting. The sentence “The bookless or paperless library is also something that is key within academic institutions” is contained within your pull quote from that BBC article, but doesn’t actually appear anywhere within the article. Where did that sentence come from?

That question aside, you have certainly provided examples of people creating digital libraries, and one of them is an example of a guy (not a librarian) back in 1995 saying that a digital library can’t succeed unless we “abandon the traditional notion of ‘library’ altogether”. But I’m still looking for examples of people using aggregate circulation statistics to support their arguments in favor of paperless libraries, which was what you said concerned you.

Here is the context:

“The bookless or paperless library is also something that is key within academic institutions. For example, it was announced last year by London’s Imperial College, that over 98% of its journal collections were digital and that it had even stopped buying print textbooks!”

http://scancommunity.com/ssc_en/can-a-library-go-paperless

My concern about the possible use of what seem to be questionable statistics (i.e. the assumption that undergraduate and graduate students have comparable library use patterns) is only anticipatory. After over 60 years in academe (as both a student and librarian), I have seen enough examples of seemingly irrational cost-savings to be ‘concerned’ about the possible misuse of statistics.

My concern about the possible use of what seem to be questionable statistics (i.e. the assumption that undergraduate and graduate students have comparable library use patterns) is only anticipatory.

No one that I know of assumes that undergraduate and graduate students have comparable library use patterns. In fact, quite the opposite. To your knowledge, has someone been making that argument?

After over 60 years in academe (as both a student and librarian), I have seen enough examples of seemingly irrational cost-savings to be ‘concerned’ about the possible misuse of statistics.

The misuse of statistics is certainly a troubling possibility. That’s why it’s so important to use statistics carefully and not to make arguments from them that aren’t sustained by the data.

The outright denial in the profession in general about trends such as this is why I can’t wait to leave it in a few months after a 28 year career. When I started I couldn’t wait to “change the world.” Internet was new and promised to provide capabilities and potential unheard of in history. Myself and others were early adopters, especially at my library where the administration at the time made sure that advances were made. Today… what? There are far too few early adopters, and too many people in the profession rationalize away information telling us we need to change and instead tell us we need to keep doing what we have been doing. We have committees and conferences and ignore the fact that Google and others have simply ignored us and are blazing a path forward at lightning speed that, with all its flaws, the public will prefer to use. We also fail to learn from this. When I bring up concerns in meetings that we are not adopting technologies that our patrons need and want I’m greeted with scowls. So, I’m out… I’m retiring just as soon as I can to make my until now part time career a full time one… in a field where new technologies and the capabilities offered are embraced. Next time you get on a regional jet to go to ALA, see if the guy in the right side of the cockpit is twice as old as the captain… it could be me. I’ll get you where you need to go safely… just please take the time to learn something new while you’re there. The profession needs it.

I find it hard to understand your statement that … “There are far too few early adopters, and too many people in the profession rationalize away information telling us we need to change and instead tell us we need to keep doing what we have been doing.” I have been a member of both the Special Libraries Association and the American Chemical Society for a number of years and it certainly doesn’t describe anyone I’ve ever met there.

I’d be delighted to find out that what I’ve experienced is not typical and that the profession is moving forward as it should be. However, everything that I’ve experienced over the last few years at conferences such as IR Day, Digital Commons user groups, VRA, and ContentDM User groups indicates that I’m not alone in my observations. The conversations at those meetings always demonstrate that I’m not alone… most participants report the same frustrations I deal with. I wish I could say otherwise.

The change from print to online has been fast and for the most part an action completed without much intellectual discussion or planning. I joined librarianship just as the Internet became a commercial entity. I considered it awesome. The transition to full-text journals online, and then ebooks breezed through the profession, exhilarating. Overall, I understand the change, only lamenting the rush to shred print just because it is print. Through the years most actions that had a just because rationale, proved to be a doomed idea. My concern still is, what has been lost intellectually? Without books/ebooks, it makes it more difficult to find a consensus, scholarly major-work that provides structure to a subject area. By relying mostly on online journal articles, blogs, statements about research, etc., do we miss the big picture? Our students undergraduate and graduate are encouraged through discipline, access online, and limited physical access to rely on short, article style online documents. Change is what the world does; have we as a profession considered what’s missing?

Sue, it sounds like you and I entered the profession at roughly the same time (late 1980s/early 1990s). Interestingly, we have very different perceptions of how our profession has responded to the print-to-online shift. My impression is that it has been accompanied by lots of discussion and consideration of pros and cons–especially in the realm of books, for which the transition from print to online was much slower than it was for journals. In particular, I’m not aware of anyone who has advocated “(shredding) print just because it is print.” But I recognize that our frames of reference may be very different; I don’t know what kind of library you work in, for example. I’m sorry to hear that your professional experience has been of a less thoughtful and careful transition process.

Thank you for your follow-up. I realized that my comment was slightly off topic. I support what has happened in libraries around the world. The “shredding” may have been over the top. My academic library experience is in a small regional campus of a larger research university. Perhaps discussions have included what will become of subject areas as we rely on smaller parses of information in the larger forums, possible including the American Library association or ACRL. I find undergraduates & graduates rely on the smaller bits, without considering the bigger context. The experience here is that even ebooks are not a large portion of the ingestion of information. This is okay; my question is, have we considered the impact of the transition from books to article size information bits?