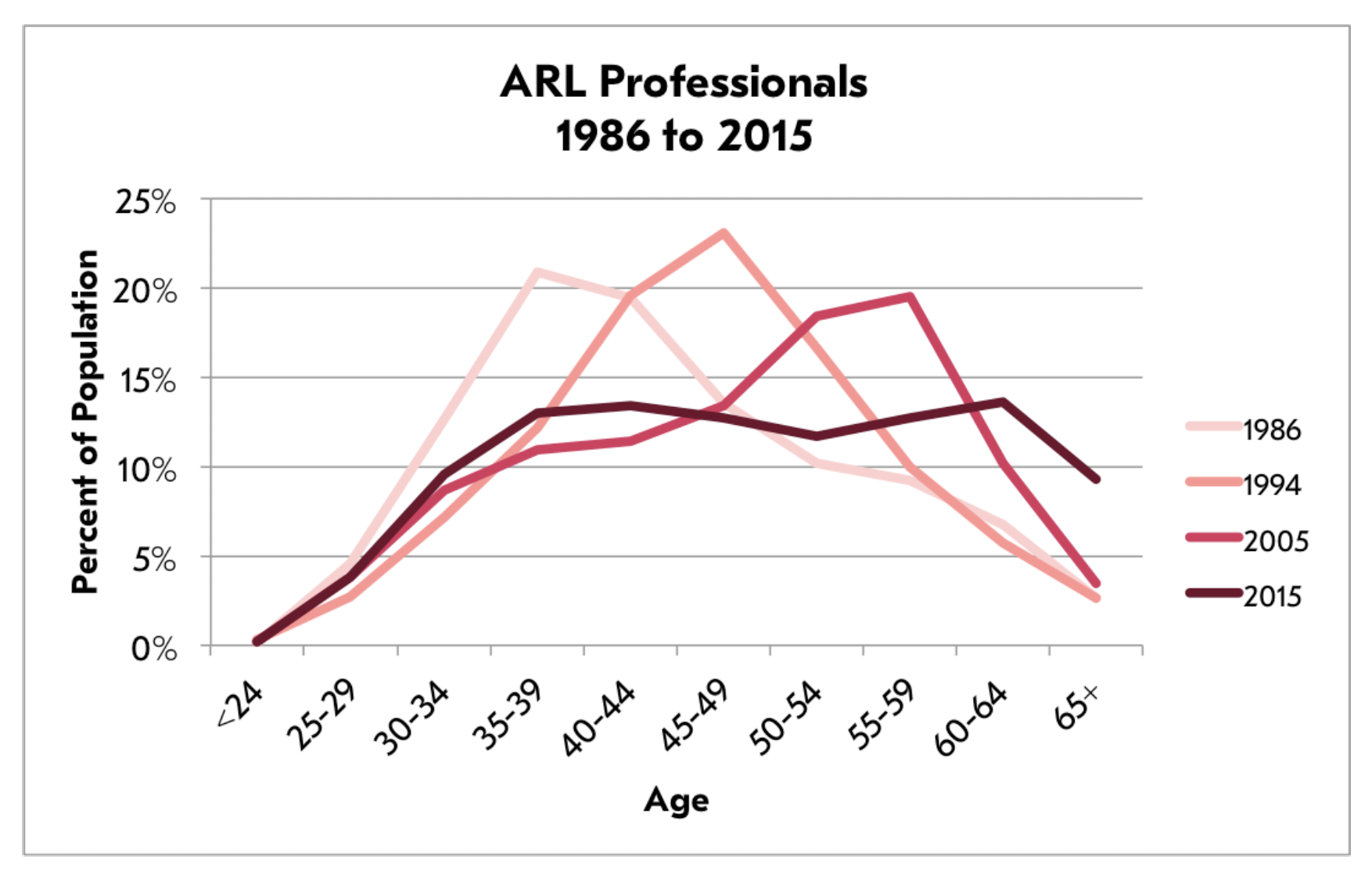

“Library professionals have never been older,” begins a report on the aging demographics of academic librarians.

The paper, “Delayed Retirements and Youth Movement among ARL Library Professions,” by Stanley Wilder, Dean of Libraries at Louisiana State University, provides key statistics on the greying profession.

The average age of library professionals in the latest Association of Research Libraries (ARL) demographic data (2015) was 49, older than at any time in the past 29 years, since the association began collecting data. Nearly one-quarter of librarians (24%) were 60 years of age or older, compared to just 9% in 1986.

Baby-boomers — those born between 1946 and 1964 — have not been retiring as expected, Wilder reports, resulting in a large cohort of older library employees. He speculates that the 2008 economic recession in the United States was responsible, in part, for librarians delaying retirement, a trend that is found in hundreds of other professions, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics workforce data. According to the National Science Foundation, less than 20% of US scientists and engineers were over 50 years old in 1993. By 2013, that percentage grew to over 34% of the workforce (S&E Indicators, Figure 3-23).

Professionals often move into more administrative roles later into their careers and librarians are no exception, except that library directors are now disproportionately older than the rest of their profession. In 1986, just 3% of library directors were 65 years of age or older, matching the age distribution of ARL librarians as a whole. By 2015, 39% of ARL directors were 65+.

The advanced age of ARL directors appears to be largely an American phenomenon, Wilder reports. In 2015, some 45% of US library directors were 65 years or older, with 14% aged 70+. In stark contrast, just 14% of library directors at Canadian institutions were 65+. Due to their small numbers, the ARL does not report the percentage of Canadian directors over 70.

While older employees bring a wealth of experience and stability to an organization undergoing transformation, they cost an institution a lot more money in salaries and overhead. More importantly, their presence prevents a new cohort of librarians from entering the profession. He writes:

The delayed retirements of 2015 have almost certainly played a role in the muted hiring levels among ARL libraries in recent years.

A massive wave of retirements in the coming years may create systemic instability to library organizations if younger librarians have not been prepared to step into administrative roles. Wilder avoids discussing succession planning in his report, painting a golden future that is ripe with new job opportunities instead.

It is hard to see, however, how hiring could remain low. More likely, the peak vacancies we expected between 2010 and 2015 are actually happening right now, resulting in the best market for research library job seekers in memory.

This rosy outlook for the future fundamentally assumes that retiring library professionals will be replaced by similarly credentialed new hires at their current numbers. It also assumes that the employment structure of libraries doesn’t change. I’m not sure that either of these assumptions ring true. Many institutions have dropped the required MLS degree for new applicants, while others have been replacing retiring directors with “coordinators.” Outsourcing of key library functions could also reduce hiring demands at ARL institutions. If you have thoughts about how staffing at research libraries are changing in the United States and Canada, please leave a comment below.

Like other greying professions, demographic data for ARL libraries warn us of a breaking wave of retirements. When the surf has settled, the beach may look completely different.

Discussion

17 Thoughts on "Retirement Wave To Hit Academic Librarianship"

A decade ago, when I started library school, people were talking about how long people had been saying that a big wave of retirements was coming. It still hasn’t happened. Our classes were geared toward educating us for administrative positions, but millennial librarians know by now that we may never get to the library administrative positions we were educated for in large numbers. Many of us accumulated additional degrees, hoping to compete in the tight job market, so there is a cohort of highly educated librarians waiting to fill positions that may be filled by non librarians.

Quite understandable, naturally, since a decade ago the Great Recession debacle hadn’t hit. When it did it created the long-term sequelae that caused many people then contemplating retirement to stay in the profession far longer than “normal” conditions would lead one to expect.

‘T’was ever thus, of course, since for a number of years after I graduated in the economic morass in the mid-’70s there was a logjam due to people at the top not retiring, thus adding to the existing glut problem of too many new grads & not enough positions available. The economic collapse of the late ’00s just made it a heck of a lot worse for potential new hires. :\

Hello Sarah,

You’re right that we’ve been knowing about the approaching retirement wave for a long time– I for one have been writing about it since ’95! All along the prediction has been that the peak retirements would come between ’10 and ’15, and the main surprise in the ’15 ARL data is that professionals had made a sudden change in behavior, delaying retirement. So now I say that the wave has to happen between ’15 and ’20, and it really does have to happen. With very few exceptions, we don’t work past 70, and folks are bunched in the oldest age cohorts as never before.

Meanwhile, I can’t help but think that the preparation you’ve put into your own career will pay off, especially now that there’s so much fluidity through the ranks.

Technology has almost made the once-important counsel of librarians somewhat akin to the need for travel agents. Finding materials is easier but librarians still provide other valuable functions. Still, it was a very different world when paper and ink was the dominant medium.

Hello DF,

Pardon me for saying this… I couldn’t disagree more. The academic library consultation services have grown enormously over the past 20 years. They look different, I’ll grant, but the only decline is at the reference desk. Meanwhile library people are more plugged in to students, classroom teaching, web based instruction modules, integrated learning systems, libguides, and websites than ever. We reach more people to better effect. The rosy thing is the true thing: we have right now is a golden age for academic library consultation services.

Stanley has followed trends in this area for the last 20 years and the chart reflects the demographic progression of boomers moving through the system over time. I understood that there was a high turnover at the ARL director level in the last 2 years and would expect the upcoming retirements would provide opportunities. Where people with required skills are being hired in libraries seems to be less about abandoning the degree than about incorporating expertise from other disciplines which I think is very healthy.

More importantly, their presence prevents a new cohort of librarians from entering the profession.

Hmmm. Why are there so many apparently unfilled jobs, ie. reposted job ads? (those for positions other than library directors). Electronic resource librarians are a hot commodity…Are these vacated or new positions? And the special academic library sector (eg. health sciences) has a whole cadre of “new generation” directors. Posted internships and practicum opportunities also seem to fill pretty quickly in the special academic library sector.

Good question, Ramune. Not a week goes by that at least 3-4 job openings are posted (& in a number of cases REposted over months) on various of the listservs that I follow. Any number of possibilities — early applicants applied without the required skills; the job didn’t attract enough applicants because salary was too low or whatever; postings demanded too much for entry-level applicants (often ironically saying “recent graduates encouraged to apply”); or God only knows what.

I know academia’s had it tough & funds are dear, but a lot of the posted salaries that show up in listings are sometimes almost insulting when framed against current cost of living, not having increased all that much over the last 15 or so years.

One of the reason positions go unfilled is the reality that American are moving less than ever. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/02/13/americans-are-moving-at-historically-low-rates-in-part-because-millennials-are-staying-put/ I have so many staff with talent and MLS degrees who refuse to consider jobs outside of their zip code. In the past, it was common for “us” to travel to take positions that would scaffold our careers. Of course, we also worked too much. Today, the emphasis on work/life balance can fall more on the side of life.

US data is affected by the rising Social Security full retirement age, which began increasing after 2002 (the last year it was 65). So from 2003 onwards the 65+ cohort includes those who have not yet reached full retirement age. I don’t know the size of the effect, but presumably it is not negligible

Sometimes I feel like a broken record saying this, but we must not make the mistake of using “ARL libraries” to mean anything more than a group of 123 highly advantaged academic libraries – well-funded, well-staffed, big collections, etc. ARL library statistics get used as a dataset too often, and the conclusions sometimes too broadly applied, because they are easily accessible and don’t require individual researchers to gather data themselves. There are somewhere around 5,000 degree-granting institutions of higher ed in the United States alone, all of which have libraries.

The “graying of the profession” is something we’ve been hearing about for at least 10 years, as someone else mentioned. This is not just at the executive level but in the rank and file as well, and it is certainly not limited to ARL libraries. ARL library directors and other high-level administrators are probably some of the highest-compensated people in the profession of academic librarianship, so it is perhaps no wonder why they choose to remain in those positions longer. What would be more interesting to study, in my opinion, is whether these statistics reflect the wider field of academic librarianship, or other subsets of interest (unionized environments, faculty vs. non-faculty status, community colleges, etc.). Those are the statistics that probably more accurately reflect the staff demographics that the majority of library professionals know.

Excellent point about the dataset. According the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median age of Librarians was 50.7 years in 2016 see: https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11b.htm

Hello Hillary,

You’re right to remind us that my data speak to ARL professionals, and that the libraries they work at are different from academic libraries generally. I think I’m pretty careful in my work to avoid confusing ARL professionals with their colleagues at other academic libraries. For whatever this is worth, the ARL data has over the decades proved largely consistent with the Current Population Survey, which includes gender and age data for U.S. librarians of all kinds.

As to your point about ARL directors delaying retirement due to compensation: the thing that’s interesting here is the directors’ change of behavior over recent years (the comparison year isn’t in front of me). There was a time, lasting as far back as the data go, when directors were no more likely to work past 65 than anyone else. What changed? The answer could be, as you say, compensation. To know the answer to that, we’d need to have longitudinal data on director salaries. The ARL data as presented to me doesn’t allow for that kind of analysis. Meanwhile, other explanations are at least imaginable.

And finally, I second your call for the establishment of academic library datasets comparable to the every-5-years ARL Salary Survey. Actually, I’m currently feeling more acutely the lack of data relating to support staff, where we have evidence of incredible/fast change taking place. As I say in my most recent article on hiring, support staff have been nearly invisible to our professional literature, in terms of basic demographic analysis.

I agree regarding needing information on support staff. We tend to think of support staff as anyone without the MLS, however, in many cases they are doing highly critical work, especially in technology areas. In my library I’m seeing the MLS-Tenure-track faculty members decreasing and the technology-related positions increasing, when we can get the increase. In one case I moved a position from tenure-track faculty to support staff in order to hire the expertise we had to have.

Stanley,

Is it possible that the age distribution of Library Directors is, in part, the result of role reclassification at ARL institutions? Consider this scenario:

There are 3 library directors, all 65 years old. Two of them retire and are replaced by younger colleagues, both of whom are 40 years old. These younger colleagues are not given the title of “Director” but “Library Coordinator”.

If we only consider there to be one “Director,” then the average age for that role would be 65. If we consider all three to be performing the same role, the average age would be 48.3 (65 + 40 + 40 / 3).

Hello Phil,

Thank you for writing this piece, which is altogether fair and thoughtful. I’d like to respond to a couple of the mildly critical points you make:

You’re right that I don’t discuss succession planning, but I do mention it, along with the need for other measures like mentoring and organizational design. I didn’t feel like this article was the place to go deeper on any of those strategies.

As to rosy assumptions, what I’ve said is that for all the data we’ve got, going through 2015, professional vacancies are in fact being refilled. More than that, the median number of professionals employed by ARLS is gradually increasing. Now, there could be a sudden change, such as you describe. But if the trend since ’86 has been stability and even growth, even through the recession, the sudden change would be a surprise. In other words, it’s not rosy to guess that recent and long standing trends will continue. The evidentiary burden is on those who guess the trend will now suddenly change for the worse.

“Suddenly” is key here: I’ve been reading and thinking a lot about Smart AI, and feeling that in the long term, we may all be out of work. If that happens, at least we’ll have lots of good company from lots of other fields.

I can’t speak to what MLS policies are changing at what libraries, but I my article does say that ARL libraries are more likely to hire professionals that do not have MLS degrees. The change is grounded almost entirely in non-traditional positions, which leaves lots of imminent vacancies approaching in traditional areas. Here again, if the past is any indication, those vacancies will be filled with folks who overwhelmingly have the MLS degree.

As to directors not being library people, this isn’t happening much in ARL libraries. Some notable exceptions, but there have always been a few of those. By and large, if there’s any change in new ARL library directors credentialing, its that they are somewhat more likely to have Ph.Ds. I should have written about that, and didn’t.

One last point: it could well be that the hiring/staffing trends at ARL libraries differs significantly now from those at smaller academic libraries. One of the commenters on this thread says that, and I think she’s right to wonder. My strictly anecdotal experience in North Carolina and Louisiana leads me to suspect that small academics are suffering disproportionately.

Speaking as part of the wave from a small regional university in Australia, I started my career in 1986 and will be ending it next year, aged 61. I recognise that there is life beyond the library ecosystem. I would think another reason that ARL directors are working longer, is that they have invested so much of themselves in reaching the pinnacle of the profession, that their self-worth would be diminished in retirement.