On June 1st, 2011, Peter Binfield, then publisher of PLOS ONE, made a bold and shocking prediction at the Society of Scholarly Publishing annual meeting:

“I believe we have entered the era of the OA mega journal,” adding, “Some basic modeling predicts that in 2016, almost 50% of the STM literature could be published in approximately 100 mega journals…Content will rapidly concentrate into a small number of very large titles. Filtering based solely on Journal name will disappear and will be replaced with new metrics. The content currently being published in the universe of 25,000 journals will presumably start to dry up.”

If you were not present for that pre-meeting workshop, you likely heard it repeated throughout the conference. The open access (OA) megajournal was taking over STM publishing and Binfield had data to prove it. PLOS ONE, which had received its first 2010 Impact Factor (4.351) the previous summer, was exploding with new submissions. In a few weeks, the journal would receive its second Impact Factor (4.411), a confirmation that its model was both wildly successful and dangerously competitive. PLOS had discovered the future of STM publishing and others had better get on board or get out of the way.

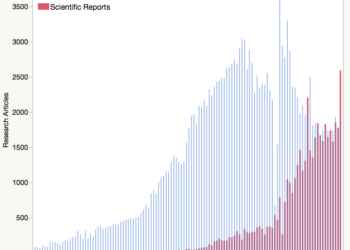

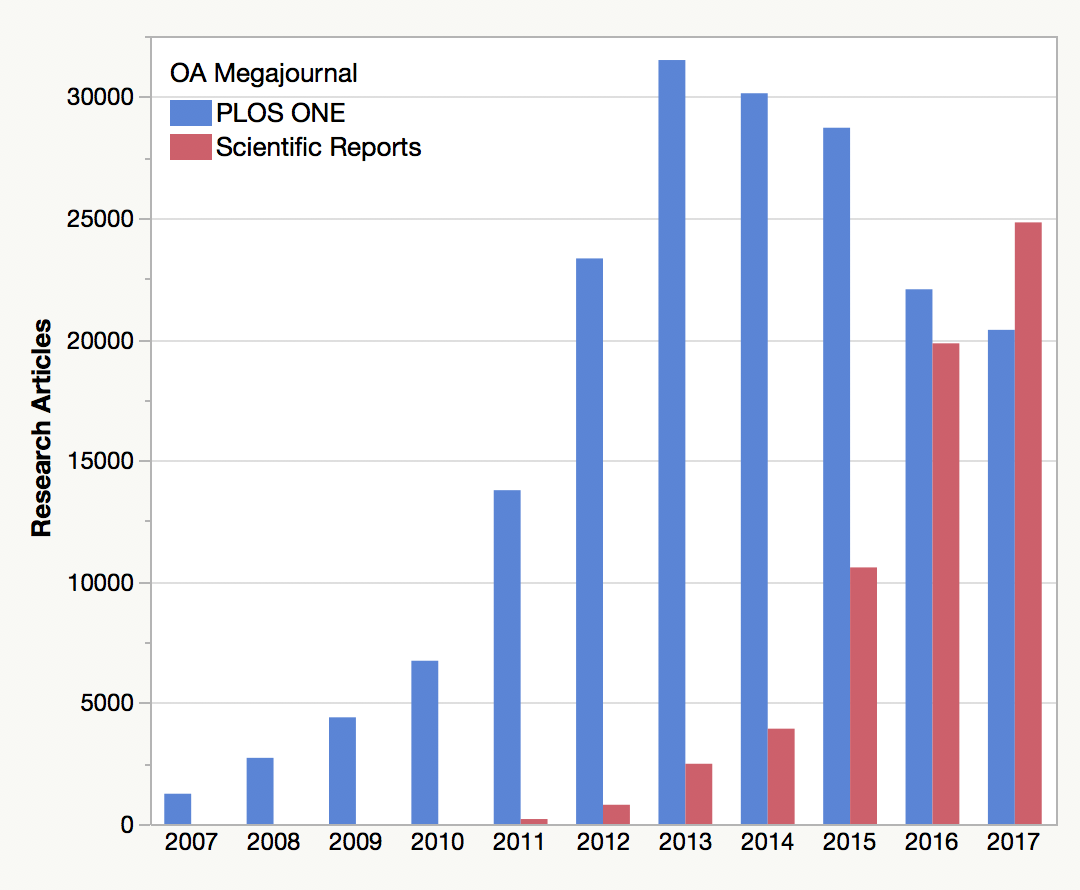

Only, to quote Yogi Berra, “the future ain’t what it used to be.” After reaching peak publication in 2013 (at 31,509 research papers), PLOS ONE output has been in steady decline. In 2017, the journal was 35% smaller than it was in 2013. At the same time, its Impact Factor — a key consideration for submitting authors — has been falling monotonically each year and now sits at 2.806.

Meanwhile, its closest competitor, Scientific Reports, overtook PLOS ONE as the world’s largest scientific journal in 2017, suggesting that these journals are competing with each other for a limited number of manuscripts. And, while there are other megajournals in this market, none are truly mega, and some, like Nature Communications, are built on a traditional editorial model that take novelty and scientific importance into consideration.

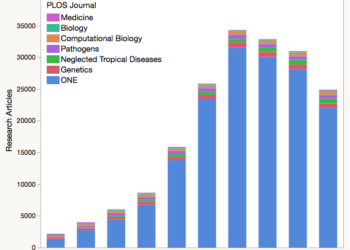

In 2012, Peter Binfield left PLOS to found PeerJ, which has a similar subject scope, editorial structure, and now, business model as PLOS ONE. Output in PeerJ has been growing modestly, but is still very small compared to PLOS ONE (PLOS ONE publishes approximately the same number of papers per month as PeerJ does in an entire year). BMJ Open, a similar OA megajournal covering medicine, is also very small by comparison.

The massive consolidation of STM publishing into a small number of very large titles, as Binfield predicted, did not come to pass. Taken together the OA megajournal market accounts for about 3% of STM output, far from the 50% he claimed.

PLOS ONE created a commodity model where indicators like Impact Factor, speed to publication, and price compete for a finite manuscript market.

If anything, OA publishing has created an explosion of titles, most of which seem to be competing for a small slice of a fixed pie. PLOS ONE created a commodity model where indicators like Impact Factor, speed to publication, and price compete for a finite manuscript market. In their two-part study of OA megajournals, Simon Wakeling and others acknowledged that the market is largely constrained by the academic reward system:

Embeddedness of journal prestige and reputation in academic practices means there is likely a limit to open access megajournal (OAMJ) growth.

Five years ago, proponents for Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) made similar predictions for the future of higher education. MOOCs were going to completely disrupt the traditional classroom, open new access opportunities for those unable to physically attend college, and, more relevantly, consolidate higher education into the hands a few elite centers that created and delivered online content.

In his piece, “MOOC Trends in 2016, MOOCs No Longer Massive” Dhawal Shah writes that the initial MOOC experience, one that was modeled on a classroom where students interacted with others in realtime, pivoted to a passive Netflix on-demand model, where students learn at their own pace and focus on completing online tests and assignments. This is the digital equivalent to the correspondence course. The MOOC has not gone away, Shah argues, it has simply discovered an unexploited niche business model:

MOOC providers have found success in monetization by packaging these courses into a credential and tying it into real-world outcomes like career advancement.

The same could be said about the OA megajournal — a model that many initially believed would radically consolidate the STM journal market, but eventually found a niche publishing technically sound papers.

Discussion

12 Thoughts on "Future of the OA Megajournal"

This is an ‘alternative facts’ usage of the word monotonically; conventionally this would mean that the PLoS article count had never risen. This is clearly not the case. Less hyperbole would help.

Thanks, Phil. As you clearly show, it’s indisputable that the landscape has changed significantly since PLOS ONE was launched 10 years ago. But does that mean that the OA megajournal has failed or not had an impact? I don’t think so. As a non-profit with a big, bold mission PLOS has two critical components – a catalytic one (seeding and nurturing change across the market) and an operational one (proving out new models). From both perspectives, it would be hard to argue that both PLOS ONE and PLOS more widely have not been incredibly successful. But clearly, there are both new challenges and new opportunities, and our task now is to evolve both PLOS’s journal portfolio and the organization more widely to answer the next big problems in scientific communication that encompass but also move beyond OA.

One thing I’ve never understood about the OA megajournal model is the opposition to filtering by quality or interest level. They absolutely should accept all papers that are technically sound, but that doesn’t prevent the editor or reviewers from giving each article a score out of ten to indicate how important the research is. Such a step would make subscribing to a PLOS ONE table of contents plausible again, as one could sign up to see only those papers in e.g. microbiology with an interest score above 8.0.

A more daring step would allow megajournal editors to say which other journals they think the article could be suitable for. Readers know which journals publish papers relevant to them, and could therefore subscribe to the ‘suitable for Journal X’ Table of Contents from the megajournal too. After all, a journal is just a label.

Tim, you raise some interesting ideas, a number of which we’ve been working on. I’m not sure I would frame these as “quality”or “importance” filters – our goal is to move review away from inherently subjective assessments. But I do think that there are useful ways to develop community input in terms of both review and curation and as you suggest, making it quick and simple may be the key to actually getting people to do this. And it’s interesting to think how these could be built over time to provide an evolving picture of a work’s reliability and significance throughout its useful lifetime.

My hunch is that getting ‘read-worthiness’ input from editors and reviewers will be a more stable and complete system than hoping for community input after publication, as altmetrics etc are very prone to Matthew effects and definitely not objective.

On a slightly related note, did you see Alejandro Montenegro’s proposal for ‘Post-Acceptance Pre-Publication Open Peer Review*’? Manuscripts get conditionally accepted after standard anonymous peer review, and then posted on a special section of the journal’s website for a month. During this stage anyone can submit additional comments to the Editor. After this period the Editor makes a final decision, perhaps asking for additional revisions in response to concerns raised at the public commenting phase.

This setup fixes a few issues with post publication peer review. First, the horse is still in the peer review barn, so public comments lead to actual changes in the manuscript. This makes commenting much more worthwhile. Second, the comments are moderated by the Editor, so any junk or maliciousness gets discarded. The latter also means that commenters can be anonymous to the authors and still have their integrity/competence certified by the Editor.

*https://molbiohut.wordpress.com/2017/11/18/part-2-of-publishing-is-not-the-end-thoughts-about-discussions-on-published-manuscripts-and-author-engagement/

**blame me for the acronym, not Alejandro

Hi Tim,

Jumping in here a bit downstream, but my understanding of the rationale behind the megajournal approach is that we can’t accurately determine an article’s significance to a field in advance, it has to be out there in the wild for a while before this can be known. So one accepts everything that is valid, and lets time sort out what’s interesting/important. If the editors jumped in and started rating articles, it would invalidate this philosophy, and you might as well just split the megajournal up into a series of smaller journals, PLOS ONE-A, PLOS ONE-B, etc., each with its own standard for acceptance.

As for the proposal you mention for PAPPOPR, I haven’t read it, but what happens to an article that is published in a journal’s special section, then gets rejected by public reviewers? Does that article disappear from the site? Can it ever be published elsewhere given that it has now been previously published? How willing are authors to have their failures publicly displayed? And what happens to the many, many articles that don’t receive any public comment (which would be the majority)?

Tim and David, I like this idea but an alternative is to shift that more informal commenting and review to preprints rather than an article (or submission) attached to a journal. I’ve now heard many stories from scientists who’ve received incredibly helpful comments on a preprint that have helped to share the final article in tandem with more formal and traditional peer review.

Agreed — either it’s published or it’s not published, and trying to have it both ways is problematic. But to your point on preprints, note that most of the anecdotal evidence I’ve heard is that the comments to authors come through private channels like email, rather than public posting of comments. There’s still a great reluctance (and a reasonable one) to publicly pointing out the errors of colleagues.

Has anyone experimented with having an Editor assigned to each preprint? The private email channel for comments is great (and I’ve used it myself), but perhaps there’s another channel for private anonymous comments that are moderated and guaranteed by an Editor?

I believe all biorxiv comments are moderated (no idea how this would scale). But assigning an editor creates overhead, which means costs, which means you’d need more of a business model for preprints than currently seems to exist.

Jumping back up the thread, I don’t think including a judgement about the significance of a paper is antithetical to the concept of a megajournal – it’s just that significance plays no role in the editorial decision.

After all, reviewers and editors are members of the broader community that will be doing the long-term judgement of significance. Having their views alongside the published paper just means they get to kick off the conversation. They’re well placed to do that because they’re all experienced researchers who have also read the paper in depth.

Fascinating article, Phil, but you state “these journals are competing with each other for a limited number of manuscripts”. Yet if you look at your bar chart and add the number of research articles in PLOS ONE and Scientific Reports together, it shows a continuing growth in the total number of articles published in megajournals overall.