Prediction is generally a sucker’s game, as we all know both from our own embarrassing attempts and from seeing failures of clairvoyance around us all the time.

It seems to me that several things can get in the way of our ability accurately to see what’s coming. One of them might be a restless dissatisfaction with things as they are: the worse things look to us right now, and the more we want them to change, the more we may be likely to think change is inevitable. (I see this as the combined effect of both general wishful thinking and a persistent, Victorian-era belief that society is always progressing.) Another might be an enthusiasm for Shiny, Exciting New Things: if someone predicts a cool new development, some of us may tend to believe the prediction because we like things that are cool and new.

There’s a flipside as well, though, and that’s the equally human tendency to dismiss predictions of discontinuity because of our own investment (emotional, temporal, or financial) in continuity. At the risk of belaboring the obvious: in my experience, librarians who have invested 20 or 30 years of their careers in cataloging or collection development tend to be less open to radically new ideas about the catalog or the collection than those who haven’t, and publishers that have spent 100 years building a business by selling subscription bundles tend to be less open to predictions of article-based purchasing models.

So, with all of this in mind, what do we think of the massive open online course, or MOOC: educational megatrend of the future? Flash in the edu-pan? Is it going to be the new iTunes or the new Second Life? (You remember Second Life, don’t you? No? Ah.)

A year and a half ago, Sebastian Thrun brought the MOOC to general public awareness when he launched an introductory MOOC on the subject of artificial intelligence, and reactions to the MOOC’s sudden prominence were both widespread and highly varied: MOOCs “pose a great threat to… literacy“; no, they represent the future of global education. MOOCS can’t offer authentic learning; yes, they can. In recent months, the initial excitement seems to have settled into a general skepticism and a feeling that perhaps the MOOC was all shiny ephemeral promise and no boring, sustainable follow-through.

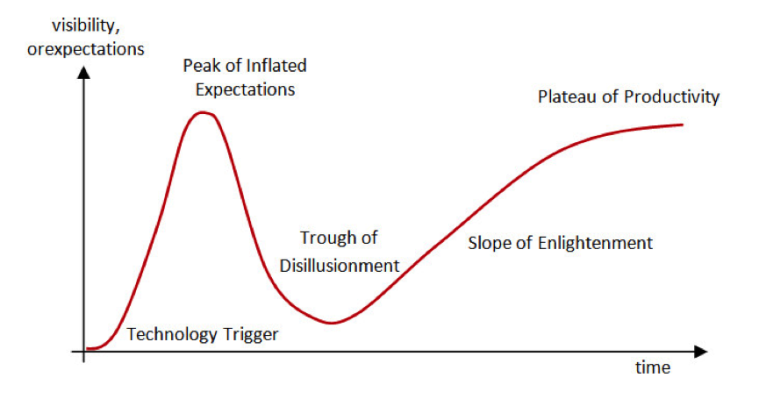

But last month Jonathan Tapson, an acting dean at the University of Western Sydney, floated an interesting hypothesis on his blog: that the dynamic we’re seeing with MOOCs is an example of the Gartner Hype Cycle, which looks like this:

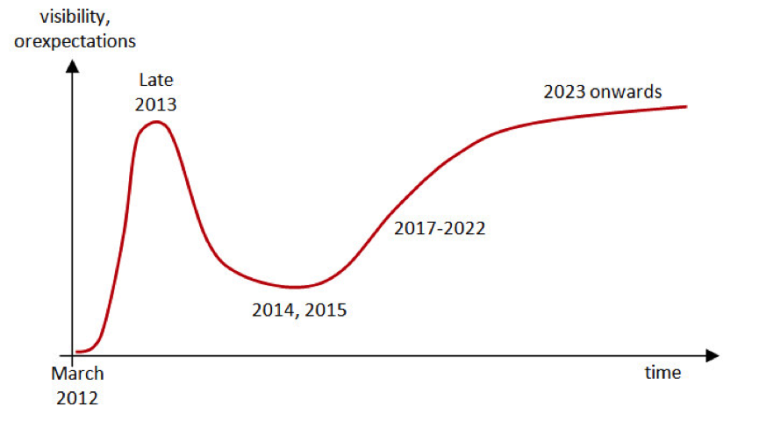

Tapson’s suspicion is that we’re past the Peak of Inflated Expectations (MOOCs are the future of global education!) and entering the Trough of Disillusionment (Hey, MOOCs haven’t cured cancer!), but that in the long run it will to turn out that they’re slowly but deeply disruptive of traditional higher education. He presents a chart of what he thinks will happen with MOOCs over the next 10 years:

He lays out his prediction in these terms:

[A] gradual but inexorably rolling change in societal and professional attitudes, pinned at one end by the bedrock certainty that the elite institutions produce the elite people, and pulled at the other end by the growing awareness that free isn’t necessarily junk, and it’s, well, free. It will take 10 or 20 years, and be imperceptible while it happens, like boiling a frog.

Now, Tapson acknowledges the very real possibility that there will only be a trough, and no subsequent climb-out—the possibility that, in other words, what MOOCs are experiencing right now isn’t the Gartner Hype Cycle at all, but rather just a plain old hype-and-bust cycle. That’s not what he predicts, though. What he predicts is “a very slow tsunami.”

I’ve written about MOOCs in several previous SK columns (here first, then here, here, and here), and they have never been very far from my mind over the past couple of years. I remain intrigued and (as someone with 20 years of professional investment in traditional higher-education practices) apprehensive. Personally, I have to confess that I suspect Clay Shirky may have been right when he wrote about the MOOC emergence earlier this year. I don’t think the important question is whether or not we like the idea of MOOCs. We may think MOOCs are wonderful or that they’re terrible; that they’re elitist or that they’re insufficiently discriminating; that they’re a salutary innovation or a menace to the integrity of higher education. But I suspect the important questions—the ones that will determine the MOOC’s impact in the future—are these:

- Do MOOCs have the potential to solve problems that are real?

- Are these problems that traditional higher education has been expected to solve in the past?

- Is the traditional higher education system failing to solve them now?

- Will traditional higher education resist changing itself in the ways necessary to solve them in the future?

If the answers to these questions are all (or mostly) “yes,” then Houston, we have a problem. Shirky characterizes the rise of the MOOC and its likely impact on higher education as “a lightning strike on a rotten tree.” As someone who hopes to keep working in higher education for another 18 years or so, I wish I could be more confident that he’s wrong.

Discussion

18 Thoughts on "MOOCs and the Cycle of Hype"

A timely article, Rick, given the statement being made elsewhere that MOOCs will be “more disruptive than open access.” [http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/10/24/analysis-suggests-moocs-will-be-more-disruptive-open-access-journals]

Alongside the hype cycle, it’s worth keeping in mind Amara’s Law – formulated in the 1970s – “We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.” [http://boingboing.net/2008/01/03/roy-amara-forecaster.html]

I see there is now a journal dedicated to MOOCs – surely a badge of inflated expectations…

Rick, I must tell you that 2nd life is very much alive and being utilized in nursing and medical education, particularly as the online student population is growing exponentially. It is being used to augment and, in some instances, replace clinical teaching in physical community settings.This utilization is also being driven by the competition for student placements in physical settings.

That’s very intersting to hear, Lisa, thanks. It reflects one of things that can also happen with potentially disruptive innovations — instead of changing everything broadly, they end up changing one or two things deeply.

Some inventions don’t really come into their own until other, complementary inventions arise. There are several such developments that both c and x MOOCs need. One will result in the general population having the skills and attitudes requisite to independent learning. Another is the wide availability of quality learning content (open access). Finally, a transition in higher education from expository teaching (then obviated by MOOCs) to teaching students how to effectively use the knowledge and understandings acquired through MOOCs. Not a new idea since Bloom et. al. outlined the Taxonomy of Educational Objectives in the Cognitive Domain (1956).

Whether these pre and post-conditions will be met may have a lot to do with whether MOOCs accelerate or whither after the trough of disillusionment.

Can MOOCs possibly confer the same status of achievement as can a university degree? Currently the only thing people seem to be able to get out of them is some knowledge, ideally. Not denigrating that, but its hardly the same as having completed a university degree. I wonder if we’ll see the introduction of entire curricula built around MOOCs.

I’m currently taking a MOOC from UC Irvine on zombies, the Walking Dead, and related topics, such as human psychology and public health (so far, I’m only in week two). It’s a great deal of fun but I can’t foresee people saying that they’d forgo a traditional university education in favor of MOOCs because it wouldn’t have the same gravitas as an actual degree. And the degree, not the education, is the end goal of most university students.

It’s certainly true that MOOCs don’t currently provide formally-certified higher education. But there are two responses to that observation, I think:

1. That could easily change, and I suspect it will. Consider San Jose State University’s recent experiment with MOOCs-for-credit. I think the fact that SJSU moved so quickly to try this out is more significant than the fact that the experiment didn’t work out well on the first try. I can also easily imagine the creation of an umbrella organization that vets and “accredits” MOOCs, identifying those that higher-ed institutions can trust and facilitating an articulation system.

2. If MOOCs never become certification-granting entities, then I can imagine them taking over remediation — not actually granting credentials, but making students ready to acquire credentials (either by demonstrating proficiency or by enrolling in a prerequisite-bearing course) through established higher-ed institutions. For those colleges that see remedial teaching as a burden, this might come as a relief; for others, it would constitute a major encroachment on their market.

We don’t what’s actually going to happen, of course. But I think it would be very dangerous to write off the MOOC because it doesn’t yet do what colleges have always done.

If some sort of accreditation organization were created for MOOCs I could certainly see universities making a go at offering them. It would be so cost effective to run a MOOC as opposed to a regular class … I think. Let’s compare them.

So, you have a MOOC course that is part of an accredited degree and you charge just 100 dollars for it, to attract a lot of students. At just 1,000 students, you’ve made 100,000. Compared to a class with 20 students paying 300 dollars per credit hour, or 900 per course. That’s just 18,000, minus the adjunct faculty pay.

Of course, another thing to consider is, there are only a limited number of students out there. I think you’d see a power law coming into effect, with a few universities dominating the MOOC market and a lot of others using it as a cost saving measure.

But even so, I think universities would jump on it. Already what, 70% of faculty are adjunct? Maybe 65%? Any way universities can figure out to maximize income while minimizing cost, they’ve shown they’re more than happy to do so.

Rick, you seem to have overlooked a major development that is now many months old. Georgia Tech, Udacity and AT&T have teamed up to provide a MOOC/MS in Computer Science. The cost to complete the degree is just $6,600. Here are a few places you can read about it: Udacity, Slashdot, Slate and Gizmag.

Much of the skepticism about MOOCs comes from (a) the low “completion” rate and (b) the problem of validation and certification. These come, naturally enough, from equating them with college courses that lead to a degree. And that’s of course the model they’re based on. But I think their real value, which is often missed, is for people who need, or want, to learn something but are not after the degree or the validation, just the knowledge. So the fact that a tiny percent of, say 100,000 students in a given MOOC never complete the course (and those that do can’t use it on a resume to much effect) may miss the point that many many thousands of people learned something. So now that we have the MOOC model, it is really more a matter of aligning enough people who want to learn about X with somebody knowledgeable and effective who is willing to teach about X. It’s a somewhat (but not entirely) separate question whether that can be done in such a way to substitute for traditional college courses, or to what degree. But I think there are enough of both kinds of people (the would-be students of X and the would-be teachers of X), and enough Xs, to make it quite likely that MOOCs aren’t going to go away. What may happen is that they complement, rather than undermining, formal college education. That’s what I’d like to see happen.

Absolutely. IN 1970 Abbie Hoffman included a chapter on How to Get a Free Education in Steal This Book. His solution was to sit in on classes. You could learn the material (if you did the work), you just wouldn’t get the credential. Real MOOCs are the online equivalent.

The problem here is in talking about “higher education” in general. As with publishing, what happens depends very much on how different sectors of higher education (or publishing) operate. My prediction for MOOCs is that they have the potential to be far more disruptive for large public institutions than they do for the elite colleges, partly because the pressure from state legislatures will force public universities to achieve whatever savings MOOCs can provide in pursuit of their goal of mass education, whereas the Ivies of the world will be able to differentiate themselves even more by offering the highest quality personalized education with low student/faculty ratios. So, MOOCs will contribute further to widening the gap between the large publics and the smaller privates. What will be most interesting, perhaps, is their effect on the universities that are not state-supported but are not elite either.

Based on my multiple MOOC experiences, I think this comment nails it:”But I think their real value, which is often missed, is for people who need, or want, to learn something but are not after the degree or the validation, just the knowledge. ”

For people who are experienced and relatively successful students, MOOCs–the good ones at least, I have taken a couple that were almost embarrassing in their general badness–are a god send. Thousands of people who have completed degrees, have jobs, and like to think about the past and present are all there just waiting to discuss the latest reading or video, not to mention bringing their own resources to the table (In my first MOOC, I was dumbfounded by how hard people worked to add to the general body of knowledge being discussed, doing research completely on their own in order to share it with their peers).

But unless the American MOOCs (I think these are x MOOCs) become more like international students have described them (I think these are the c MOOCs; I get them confused all the time) with, among other things, local tutors available to help those who are struggling, a library of YouTube videos on key concepts that are difficult to absorb, central testing places and proctored exams to measure achievement, I can’t imagine how students who aren’t already good at being students i.e. self motivated and possessed of solid reading,writing, and research skills, will get much out of MOOCs.

In my most favorite MOOC, I went through the discussion threads faithfully to see which discussion topics I wanted to think about and discuss for the day, and among them were always numerous threads with labels like “Help I’m Lost”; “What Unit Are We On?” “What Am I Missing?” and “Can anyone explain the lecture to me?” I have no doubt that these poor souls ended up being numbers in the huge drop out rates that have made MOOCs, at least at present, somewhat notorious among the doubters.

I agree that MOOCs do not deserve to be in the slough of despond many are currently consigning them too, but to meet the needs of those new to academic pursuits or struggling to master academic skills, they need a serious redesign.

I think MOOCs in computer science, statistics, and other quantitative disciplines present amazing opportunities for learning. I completed a rigorous 12-week edX MOOC in biostatistics early this year and it was better than pretty much any course I took at a Big Ten university as a graduate student of engineering. I suppose I like to learn online. If MOOC providers figure out how to improve their completion rates and student engagement (I don’t think these are enormous challenges), more people might find that they like to learn online. It might simply be a better experience than attending classes — unless those classes happen to be on par with MOOCs. So while we’re wondering if online learning can ever be better than face-to-face learning, students — the consumers — might be doing the opposite: wondering if it makes sense to go to university instead of taking MOOCs or MOOC-based degrees.

Employers want skills, not degrees. Unless someone has a degree from a top institution globally or nationally, the degree itself doesn’t matter much.

Very good point. Expensive degrees most often do not include better knowledge/ skills, but a better network, that boosts your career.

This kind of comment overlooks one of the most important benefits of higher education–networking. Studies have shown that, especially for students from underprivileged backgrounds, exposure to elite colleges bring them potentially huge benefits through the networks they become exposed to through that experience. The classic book on this subject was written by my college classmate Mark Granovetter (now professor of sociology at Stanford) titled “Getting a Job” (Harvard , 1974).

Yes, students at elite colleges do have great networking opportunities, and that’s what I implied as well. But if someone is not at an elite college and wants to get a job after higher education, I think MOOCs could at some point offer better value on the whole than traditional college degrees.

How many students around the world study at non-elite colleges? How many have no intention of studying beyond a bachelor’s degree? How many start getting anxious about finding a job well before they graduate?And when they start looking for jobs and interviewing, how many become frustrated that their university experience gave them few skills to work in the “real world”?

I think the answer to any of these questions is — the majority. And maybe the majority of students around the world would say yes to ALL of these questions. So this is a pretty large population of people who’re ready for change (MOOCs) and who might give up what they’ve been used to (traditional degrees).

The key phrase in this argument is “around the world.” MOOCs have been for the world from the beginning. To take this a step further, Coursera has recently partnered with World Bank to make MOOCs more relevant for the developing world: http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2013/10/15/world-bank-coursera-partner-open-learning